I’ve known Elise Blackwell since 2003, when she took at job at Boise State University. Her first book, Hunger (Unbridled Books), had just come out, and I was blown away. The novel was short but intense, and exquisitely crafted. Sadly, her time in Boise was cut short by the pull of the south, and after two years she left to teach at the University of South Carolina. It’s fascinating watching friends go out and publish great books, and Elise has been particularly interesting because each of her books has been very different than the last. She went from a novel about the siege of Leningrad to a satire about the writing world, a historical novel about a great flood to a drama about music and loss. Now with her latest, her fifth novel, Blackwell has penned The Lower Quarter (Unbridled Books), a southern-gothic-meets-literary-noir, a potent stew of crime and art in hurricane-ravaged New Orleans, a book I believe is Blackwell’s finest. In my mind, Elise Blackwell is a bit of a rebel and represents a rare kind of freedom, an artist who goes wherever she wants, who doesn’t abide a particular shelf and is wholly invested in creating her own space in the world. I also realize Elise is one of the most humble people I know, so much so I’m sure she’s cringing at my words. Elise can cringe all she needs, because it truly is a great pleasure to chat with my old friend about her latest novel, the writer’s life, New Orleans, and so much more.

Interview:

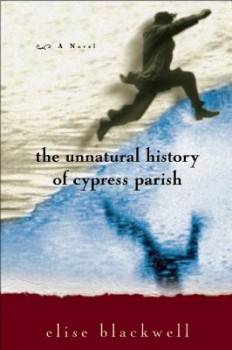

Alan Heathcock: I think writing a book, let alone a novel, is a beautiful but slightly insane endeavor. The beauty is in the depth of investment one gets into their characters and setting, the grand exercise of an author’s preoccupations and interests. The insane part is that it takes years to finish writing a novel, so many pages, research, rewrites, revision–I can’t think of too many projects, artistic or otherwise, that take the amount of time and dedication an author must give to a novel. I’ve found this has made me take great care in choosing writing projects. When I look at your list of past titles (Hunger, The Unnatural History of Cypress Parish, Grub, An Unfinished Score), I see a deep investment in a variety of subjects and settings and styles. You keep moving, reinventing yourself. I find that greatly admirable. And now you have The Lower Quarter coming out, and though we’ve seen art and Louisiana from you before, this book feels very different from your others. I’m wondering about the how/why of your projects–specifically how The Lower Quarter came into your consciousness and why you felt this was the next book you had to write?

Elise Blackwell: When I published my first novel, my great-aunt asked, “Honey, why were you even thinking about those things?” I knew she was talking not about the historical event the book fictionalized but rather the sexual exploits of the philandering narrator. Not wanting to discuss promiscuity with her, I said something about motifs and metaphors –an awkward explanation that amounted to “I don’t know.” I’d like to ask myself, “What’s the best novel I could write next?” and then write it, but that’s not the way it works. By the time I finish a book, the next one has laid claim. I can’t tell you why The Lower Quarter was the book I wrote, but I can tell you how it accrued. The first inklings came in Biloxi in 2007 while touring for my second novel. I was struck hard by how devastated much of the coast still was. I’d known that, but being there made the knowledge visceral. A few days later I was sitting on a tapestry bedspread at the Hotel Richelieu, giving a radio interview on an old black phone, and I had the strange sense that someone had died in the room (which may or may not have been true) and that I was in a film noir. Across the next years–while writing other stuff–I was thinking a lot about power relations and what it means to live in a body and how power and the body interact. I emphasize story over idea when I write, but narrative is how I think things through and those were the things I was thinking through. I put that phone in the novel as a souvenir of its origin trip.

Okay, now you have me very intrigued about a couple of things. I’ll start with following up on the notion of how power and the body interact. Can you expound on this a bit more, and maybe explain how you went from “thinking a lot about power relations” to creating a narrative that explored/expressed the truths you mined?

I always worry that ideas that feel complex in fiction sound trite in a balder statement, but here goes: Power is often differentiated by the geopolitical location of a body–on which side of a border fence a person stands, for instance–and the body itself is a site of coercion and pain. New Orleans was populated by bodies moving across borders, both voluntarily through chosen immigration and involuntarily through slavery, which is the fullest and most terrifying expression of corporeal power. Katrina was both a natural and a man-made disaster, and in both cases played out according to power differentials. Some people had the means to evacuate in comfort, escaping with their families and even pets to nice hotels. Others had to choose between staying put, being confined to the Superdome, or accepting a nearly militarized evacuation that separated families and ripped pets from children’s arms.

I always worry that ideas that feel complex in fiction sound trite in a balder statement, but here goes: Power is often differentiated by the geopolitical location of a body–on which side of a border fence a person stands, for instance–and the body itself is a site of coercion and pain. New Orleans was populated by bodies moving across borders, both voluntarily through chosen immigration and involuntarily through slavery, which is the fullest and most terrifying expression of corporeal power. Katrina was both a natural and a man-made disaster, and in both cases played out according to power differentials. Some people had the means to evacuate in comfort, escaping with their families and even pets to nice hotels. Others had to choose between staying put, being confined to the Superdome, or accepting a nearly militarized evacuation that separated families and ripped pets from children’s arms.

The novel doesn’t depict those events–the setting is post-Katrina–but those scenes were in the background for me. My thinking about power is articulated through both character and plot. Eli, the detective figure, is from a place with a contested and unstable political definition, which is partly responsible for his recent imprisonment. Johanna has been a victim of another form of incarceration and has variously been an involuntary and voluntary migrant. Clay has the power of money but is also subject to his father’s power. Power is also enacted directly on bodies in the novel. The most obvious example is sexual power. Clay prefers sexual dominance but only with a willing partner, while Marion–a submissive–gains sexual power by relinquishing control. The body is also a site of painful alteration, whether Marion’s tattoos or the scarring on one of her clients or Clay’s unusual decision late in the novel. Of course I’m telling a story, so none of this adds up to a theory or even an argument.

I think your thoughts on power and the body are brilliant, and they definitely direct the urgency of the story. It’s potent. Of course, this power dynamic (sex, money, crime) is at the heart of noir, which brings me to wonder about your decision to go for something in the realm of a noir novel. Have you always been a fan of the genre? I know with my own book, Volt (Graywolf, 2011), with several stories that address crime/violence, I got a tiny dose (a few isolated incidents) of “literary” folks looking down their noses at my work. I found the reaction strange and disappointing because I was earnestly using the hull of a crime story to get at something much deeper (I was trying to write literature). Do you worry about the perceived literary merit of your book if we start tossing around the word “noir”?

I’ll only accept that adjective if you’re using it as generously as a British friend who refers to diner food as brilliant. But thanks. When you were writing Volt, you described your stories as “knob goth,” which I thought was funny and accurate but also incomplete and maybe a little dismissive of the literature you were writing. I remember one of the most crime-focused stories–one told in the point of view of the fabulously nuanced woman sheriff–as one of the most literary of all. I’m fatigued by the idea that there is police tape around content, that literature can’t take any aspect of existence as subject matter. The real world contains crime and domestic melodrama and romance and comedy and horror and the erotic, and it’s ridiculous to ask writers not to ponder these subjects just because they’re also–often in their most simplified versions–the stuff of genre fiction. But with The Lower Quarter it’s true that I’m working with not just the material of noir but some of its tropes. In a traditional noir, Eli would be the only point-of-view character–maybe even a hard-boiled narrator looking up Johanna’s skirt at her “mile-high legs.” I didn’t want that, but I wanted the reader’s knowledge of that kind of story to inform her reading. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want to market The Lower Quarter as straight noir, because it would disappoint. My final aims are different even if the book’s worldview isn’t so far off.

I’d say that The Lower Quarter reminds me as much of the work of Patricia Highsmith (The Talented Mr. Ripley, Strangers on a Train, The Price of Salt) as it does Walker Percy (The Moviegoer). I greatly admire both of these authors and mean the comparison as a high compliment–I hope it’s taken that way. Percy, of course, has the stamp of approval in literary circles. I was shocked to find that once I started my MFA that one couldn’t openly speak of Highsmith. After we’d workshopped a particularly boring story, I remember telling my classmates that Highsmith had written a really great book on how to handle plotting and suspense. They reacted with a kind of horror that I would even say the words plot and suspense (hahaha).

Then I read somewhere that Nabokov had been influenced by Highsmith’s The Price of Salt when writing Lolita (a novel my classmates frequently cheered as a masterpiece) and that set me to the task of figuring out why one author made it over the “literary” bar and another didn’t. I read all the great literary novels I could get my hands on, and read a lot of popular fiction, too, and I found good and bad in both. I greatly admire authors like Cormac McCarthy, Emily St. John Mandel, John Banville (as Benjamin Black), who seem to go where they please.

Then I read somewhere that Nabokov had been influenced by Highsmith’s The Price of Salt when writing Lolita (a novel my classmates frequently cheered as a masterpiece) and that set me to the task of figuring out why one author made it over the “literary” bar and another didn’t. I read all the great literary novels I could get my hands on, and read a lot of popular fiction, too, and I found good and bad in both. I greatly admire authors like Cormac McCarthy, Emily St. John Mandel, John Banville (as Benjamin Black), who seem to go where they please.

I put you in that category, as well. I wonder why you feel this “police tape” (as you called it) exists, and if there are any consequences to the separation of what’s perceived as “literary” versus “genre”? As an author and professor, do you worry about defining the terms “literary” and “genre”? If so, how do you personally define something as being “literary”?

I’m happy to accept that compliment just as I was happy that John Banville blurbed The Lower Quarter as Benjamin Black–a nod to its content and probably an act of kindness intended to boost sales. You know, I think that things have changed in recent years and people are stepping over that tape more easily. Highsmith’s reputation has been rehabilitated, and literary writers have been using the stuff of genre to create fascinating work that has been critically well-received. It may be more dangerous now to criticize than to borrow from genre, as evidenced by the grief Jennifer Egan received over her comments on chick lit. Elite is derogatory, and sales numbers are used to bolster arguments that genre fiction be given equal access to literary prestige. Gleeful anti-intellectualism has serious consequences for science and for politics. I don’t worry so much about its literary ramifications, though I will say that reverse snobbery serves us no better than snobbery.

Banville is an interesting case in that he writes his literary novels and his noir under different names. People have criticized him for saying that Banville books take years while he can write a Benjamin Black novel in mere months. In response to this expressed dismay over his statement of a fact, he’s said that he’s not arguing that crime fiction is inferior to literary fiction but that they are different things. People can and do read both. Some people can write both, and there are books that absolutely belong in both categories at once. But the overlap is not large. I’ve had students tell me they’re “bending genre” when what they mean is that they are writing straight genre in quality prose. This doesn’t mean that literature can’t be written about zombies or a young woman’s rocky road to romantic contentment or a murder solved by a hard-boiled detective. Nor does it mean that genre fiction can’t be smartly written, even lyrical. Yet distinctions are useful so long as they aren’t restrictive. With beginning students, who I encourage to give literary fiction a go, I use a working definition of “fiction that aspires to be art.” When pressed, I’ll explain that literary fiction distinguishes itself in two ways. First, it seeks not only to entertain but also to discover or at least look for complexities about the human condition. Second, because of this aim, it observations and language unsettle more than reassure. For this reason, its language also has a sense of itself as medium. I think here of O’Connor’s famous comment that a painter should like the smell of paint.

I love that you say it’s literature’s aim to unsettle and, “For this reason, its language also has a sense of itself as medium.” In fact, I was just reading an article [entitled “The Audacity of Prose,” published on The Millions in June] you shared on social media, in which Chigozie Obioma argues the importance of the artful use language has been diminished in contemporary culture, writing:

“It is therefore necessary that writers everywhere should see it as their ultimate duty to preserve artfulness of language by couching audacious prose. Our prose should be the Noah’s ark that preserves language in a world that is being apocalyptically flooded with trite and weightless words.”

I’d love to hear your thoughts on Obioma’s challenge to us writers, and also have you more thoroughly explain what you mean that literature (and thereby our prose) must work to unsettle?

Obioma would probably object to my shorthand reference to the self-consciousness of language–and as someone who writes relatively spare prose I have a quibble or two with his piece–but his central argument is correct and crucial. I’ve been trapped on airplanes with seatmates spouting business jargon, and in researching a new novel I’ve read through some of the “literature” of self-help. Canned language blocks rather than reveals the world. Its pat quality closes mystery. The purpose of art–a purpose of art, anyway–is to show us the world in a new way rather than tell us what we expect. Cezanne’s shapes, hues, and levels of color saturation make me see his subjects–whether a French hillside or a human face–in ways that are revelatory.

Obioma would probably object to my shorthand reference to the self-consciousness of language–and as someone who writes relatively spare prose I have a quibble or two with his piece–but his central argument is correct and crucial. I’ve been trapped on airplanes with seatmates spouting business jargon, and in researching a new novel I’ve read through some of the “literature” of self-help. Canned language blocks rather than reveals the world. Its pat quality closes mystery. The purpose of art–a purpose of art, anyway–is to show us the world in a new way rather than tell us what we expect. Cezanne’s shapes, hues, and levels of color saturation make me see his subjects–whether a French hillside or a human face–in ways that are revelatory.

If the purpose of art is to show us the world, and you’ve written about both visual art and music in your novels, why were/are you drawn specifically to being a novelist–to both language and to story? Is there something you think writing novel can do that attracts you to the form? Or do you think it’s something just set in your DNA that calls you to the writing?

Many things about the form keep me at the work–including its capacity for holding ambiguity–but my attraction precedes these. Reading novels was one of my great childhood pleasures, and I was writing fiction at age five. As I’ve said, the novel is how I think. I know some visual artists who, when asked to discuss their work, become inarticulate and move their hands a lot. When I’m asked to speak about something, I tend to reach for story. I also love the medium and get excited about office supplies. In my sole attempt at satire, I described a character’s love of pairing never-before-joined words. I was making fun her, but I think it’s pretty clear where my sympathies pointed. There are other kinds of writers–many of them terrific–who write more from idea than out of a sense of story or language, but I think that most novelists who work from a love of medium were drawn in young. There are wonderful exceptions, but mine is a story you hear over and over. Because you asked the question, I’m assuming it’s something you’ve asked yourself….

I was drawn in young, though I didn’t realize it, or act upon it, until much later. I grew up in a place where books and reading weren’t really championed, especially not for a boy. I took my first writing course, and made my first attempt at writing creatively, my junior year in college. That said, some of my most potent/memorable experiences were from books, even if I was reading in a kind of seclusion (my mother was/is a huge reader, but I really never had peers who read and never really had anyone to talk with about books, so it felt like a seclusion).

Probably my earliest memory of feeling the power of literature was when reading Charlotte’s Web. There’s a part in that book when Wilbur the pig is begging Charlotte the spider to help him not meet the fate of the farmer’s butchering, and in the dark of the barn Wilbur cries out, “I don’t want to die.” That part just tore me up, and I remember weeping and sneaking off into the bathroom so no one would see me crying. But it stuck with me. I kept reading in secret–Jack London’s “To Build a Fire” terrified me, as did Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot (I slept with a Lincoln Log cross beside my bed), and I soon moved on to Raymond Chandler and Cheever and Hemingway. Flannery O’Connor absolutely slayed me–it was like I’d had my eyes replaced once I’d closed up her collected stories, as the world looked completely new and different.

Now as a writer I find it deeply satisfying when someone comes up and says that my work hit them in some powerful way. There really is a deep intimacy passed between author and reader. What were some of your most powerful reading experiences? What books/authors do you think most helped form your aesthetic?

I bawled reading Charlotte’s Web, too. Through that book I also learned something about the nature of empathy and fiction’s role in cultivating it. During elementary school, I particularly loved books that opened hidden spaces and worlds, from The Secret Garden to the Boxcar Children series. A grandmother who taught English quickly had me reading Greek mythology and such southern writers as Welty, O’Connor, Hannah, and Percy. (Speaking of the body, “Good Country People” did me in.)

I bawled reading Charlotte’s Web, too. Through that book I also learned something about the nature of empathy and fiction’s role in cultivating it. During elementary school, I particularly loved books that opened hidden spaces and worlds, from The Secret Garden to the Boxcar Children series. A grandmother who taught English quickly had me reading Greek mythology and such southern writers as Welty, O’Connor, Hannah, and Percy. (Speaking of the body, “Good Country People” did me in.)

One of my most memorable reading experiences should not have happened: at thirteen, I found de Sade’s Justine in a house I was visiting. In high school, I was something of a closet existentialist and was attracted to books that explored the psychology of guilt, including perhaps too much Dostoevsky. I mention de Sade and Dostoevsky here, because I think some of the seeds for The Lower Quarter can be found in them, though my novel is nothing like either. For awhile I wrote too much under the influence of Faulkner–a professor in grad school was driven to call my work “neo-Faulknerian crap”–but my more mature aesthetic was shaped by the early novels of Ondaatje as well as Howard Norman, J.M. Coetzee, John Edgar Wideman, and perhaps Andrea Barrett. I’m not saying I write like the luminaries—I wish—but in each there’s an approach to obsession, a use of juxtaposition to generate meaning, and competing impulses toward the lyrical and the economical that resonate with me. It’s funny; the books I love are quite similar to one another, while the books I like a lot range wildly.

I’d love to hear a bit more about your understanding of how fiction has a role in cultivating empathy. In my opinion, an individual’s ability and desire to empathize has been greatly damaged by this digital age (we’re able to cater our lives to just interact with information and entertainment sources that support our own worldview and therefore intentionally and knowingly segregate ourselves from those not like us), and the role of literature is vital to counteracting this great separation. Do you think quality fiction can save us from ourselves? If I could grant you the wish of having everybody in the world read the same books, what are a few titles you’d offer up?

I’m not naïve enough to argue that writing or reading fiction necessarily makes someone a better person—I know too many misanthropic, narcissistic, and otherwise badly behaved writers to argue that—but good fiction does push us to imagine in detail what it might be like to live another life. As many have noted, we think we’re assholes because we’ve had a bad day and other people are assholes because they’re assholes. Fiction can change that setting, at least sometimes. That said, I worry that segregation by worldview also happens with books. Some readers seek only characters they can “relate to” and books that confirm rather than unsettle their beliefs. For that reason and others, I would not wish for everyone in the world to read the same books. Not even my favorites.

So, wait, you’re handing back the magic wand unused? We can’t have that! Hahaha. Okay, same magic wand, different use–if you can use the wand to make any changes to the world of book publishing/selling, what would they be? For example, I’d make book publishers/sellers work much harder to get men reading, and more specifically men reading fiction, and even more specifically men reading fiction by women authors. You?

I’ll use the wand this time. Lots of books are published, but few are noticed. Papers tend to review many of the same books, and readers understandably want to weigh in on This Season’s Big Book or The Controversial Book. Overlap is great for conversations–I host a literary series based on that premise–but the entire country shouldn’t be reading the same dozen or so books. I’ve received emails seeking my opinion on Go Set a Watchman, and their senders seem surprised that I’m fine not having one. I probably won’t read that book, but I’d love to tell you what I think of Toni Sala’s The Boys (translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem, Two Lines Press, 2015), or Jenny Erpenbeck’s The Visitation (translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky, New Directions, 2010), or Victor LaValle’s Big Machine (Spiegel & Grau, 2009), to name books in my line of vision at the moment. Of course diverse reading is also happening–and here is where we should thank booksellers and book bloggers and many reviewers–but there are strong forces against it, including the concentration of marketing dollars. Naturally, I also love your idea.

In reading The Lower Quarter, I sensed that you have both a deep affection for New Orleans, but also see it for the dynamic and complicated place it’s always been. With the coming 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, I wonder if you’d share your impressions of how the city has changed over the decade?

In reading The Lower Quarter, I sensed that you have both a deep affection for New Orleans, but also see it for the dynamic and complicated place it’s always been. With the coming 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, I wonder if you’d share your impressions of how the city has changed over the decade?

New Orleans was and is my favorite American city and maybe my favorite city period. It’s also a complicated place with myriad problems–something true both before and after Katrina. Much of the journalism in the anniversary run-up was thoughtful, but some of it was outrageous and offensive. I’m thinking here of pieces suggesting that positive aspects of recovery mean that the mass death and destruction had a silver lining–or even was a good thing–as well as those treating Katrina as a metaphor rather than a literal tragedy. The dead will not return, and recovery has been variegated for the living.

If you’ll forgive a story I’ve told before, I was sitting in a restaurant on Chartres Street in 2010 or so. It was very much a post-Katrina place, where the building screamed “old New Orleans” but the menu did not. From behind his hedge of fresh herbs and flavored bitters, the bartender was handing out something he called Magnolia Shorties. This is a scene I couldn’t have imagined in fall 2005: professionals and hipsters and tourists–probably 90 percent white–drinking a cocktail named after a bounce star murdered in a gang hit not too far away. Maybe Magnolia Shorty would have liked the fact that the drink was named after her. And certainly the influx of more young “creatives” has helped many neighborhoods. And definitely I would rather drink a Magnolia Shorty than some disgusting machine-made drink being sold to drunken conventioneers and frat guys on Bourbon. But there are some things wrong with the picture, too.

Okay, now we’re going to head into the lightning round, Elise, where we’ll effortlessly learn super deep stuff about you in a very short amount of space. How modern is that? Hahaha. Ready? Here we go:

Beethoven or Mozart?

Since Bach isn’t a choice, Beethoven.

Werewolf or vampire?

To be? Werewolf. To sleep with? Vampire.

Whiskey or wine?

Wine before midnight, bourbon after.

Mountains or beach?

Someone once told me they’d never seen anyone enjoy water more than I do.

Favorite sports team?

Saints, Pelicans, LSU anything, any team my kid plays tennis for, and the Tampa Bay Rays as long as my nephew stays on the team.

Dead author you’d most like to take to dinner?

Flaubert!

Dead author you’d most like to take to a party?

Chekhov if it’s a date. Otherwise Dawn Powell.

Dead author you’d hate to have to deal with as one of your students?

Mailer.

What is your deepest darkest secret, the thing you’re most ashamed of and have never ever told anyone?

Don’t be ridiculous.

If you were ordered by a totalitarian government that you must cease writing and take on another career, what would you do?

Farmer or cook.

For those who are hosting you for upcoming readings, what are your favorite foods and do you have any dietary restrictions?

I don’t evangelize, but I eat only oysters and plants and stuff made out of plants. Within that, I like absolutely everything, including chocolate. Fresh fruit is always what I want for breakfast.

What’s one piece of advice you’d give to your younger-beginning-writer-self on the topic of how to be a writer?

Work harder: worry less about gaining experience and more about losing time.