Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

In today’s feature, Natalie Bakopoulos reviews Damon Galgut’s In a Strange Room. The review was originally published on August 8, 2010.

In a letter to Georges Izambard (May 1871), Arthur Rimbaud writes:

I want to be a poet, and I’m working to turn myself into a seer: you won’t understand at all, and it’s unlikely that I’ll be able to explain it to you. It has to do with making your way toward the unknown by a derangement of all the senses. The suffering is tremendous, but one must bear up against it, to be born a poet, and I know that’s what I am. It’s not at all my fault. It’s wrong to say I think: one should say I am thought. Forgive the pun.

I is someone else. Tough luck to the wood that becomes a violin, and to hell with the unaware who quibble over what they’re completely missing anyway!

Whether “I is someone else,” or perhaps the more recognizable “Je est un autre” in the original French, the statement disorients with its dissonant, playful play on the subject-verb agreement. Damon Galgut, in his superb novel In a Strange Room––better perhaps described as a collection of three linked novellas––similarly distorts the I as both first person and third. The storytelling alternates between these two perspectives, often in the same paragraph and sometimes in the same sentence. Soon, in the same way we become accustomed to a new locale when traveling, this point of view choice asserts itself not simply as artistic quirk but as part of the story itself. The protagonist, a young South African man also named Damon, reflects upon his younger self: “Looking back at him through time, I remember him remembering, and I am more present in the scene that he was. But memory has its own distances, in part he is me entirely, in part he is a stranger I am watching.”

In a Strange Room chronicles Damon’s travels as he journeys from Greece, to various countries in Africa, to India. Traveling, in general, disorients. We are displaced from our normal locations, we are observing places that are not our own, and our minds constantly compare the new, foreign place with the familiar one. Like Rimbaud’s process of becoming a seer, the state of traveling might be a process by which we project toward the unknown by a derangement of the senses. To travel is to step into a sort of duality.

Duality is a major theme of the novel. When the Gulf War begins, Damon watches it on television in a public square in a Greek town: “Everybody has been waiting and waiting for it, now it’s happening, it’s happening in two places, at another point on the planet and at the same time on the television set.”

Yet this produces a feeling of remove, of being almost invisible as a traveler. Damon says of his traveling companion: “it feels at times that for Reiner this country is only a concept, some abstract idea that can be subjugated to the will…. nothing matters except himself and the empty place he’s projecting himself into.” As if the empty place fills with the traveler and empties upon the traveler’s departure. Damon later muses of other travelers: “…it never seems to occur to them that the conditions they found horrible and disgusting are not part of a set that will be struck when they have gone offstage.” Here, the traveler is simultaneously self-important and insignificant.

And this allows for a certain lightness. The idea of travel implies a certain freedom: “[B]y shedding all the ballast of familiar life they are each trying to recapture a sensation of weightlessness they remember but perhaps never lived, in memory more than anywhere else traveling is like free fall, or flight.”

However, as the book progresses, this sense of freedom becomes, ironically, an agonizing weight. When Reiner and Damon met traveling in Greece (“on that lonely road they looked like mirror images of each other”), there was a sense of parity in their relationship. Two years later, when they decide, rather randomly, to travel through the African country of Lesotho, a country completely contained within the borders of South Africa, the power dynamic shifts. The relationship starts to strain when they must deal with an oncoming storm: “Rolling in from separate points on the horizon are two massive storms, their paths set to collide roughly where they are standing.” Though they manage to survive the storm from inside their tent, here in this country buried within a country is where their relationship begins to sour. The power discrepancy is huge, and Reiner holds the reins. Reiner’s weight seems to constantly bear down upon Damon:

An image in a mirror is a reversal, the reflection and the original are joined but one might cancel each other out. So underneath the journey is a conflict, almost another journey in itself, a struggle for ascendancy, which as the days go by begins to push through to the surface.

Later, after the pair has split for good and the two are both back in South Africa, though not together, Damon hears of Reiner’s doings, and Reiner of his. “The two stories push against each other, they will never be reconciled, he wants to argue and explain until the other story disappears.”

Duality is not only manifest here in the idea of our former selves as strangers and in the sense of one reality obscuring another, but also in the sense of multilayered selves and multilayered worlds. Even the structure of the book suggests this. Each section recounts separate trips and people, yet the events of the previous section are not referred to again as they might be in a traditional novel. But that doesn’t mean that no action–reaction is at play. The causality is not dramatic but emblematic: the more Damon travels, the more like “real life” it begins to feel and the more bleak it becomes. And with each novella the overarching mood of the previous seems to hang over the subsequent.

For instance, the sadness and confusion of his relationship with Reiner, though not directly mentioned, seems to be a part of the grief that Damon speaks of as following him on his travels in Zimbabwe. It’s as if Reiner has stayed with him, like the layer of sadness from a dream whose content you don’t remember but whose overarching mood you do: “Something in him has changed, he can’t seem to connect properly with the world.”

Lesotho / Image by Mandavi

Furthermore, this divide of the self becomes more intriguing, more endearing, and even more heartbreaking in the second novella. If early in the book travel was seen as a positive lightness, a shedding of ballast, as the book progresses this lightness becomes oppressive. “His life is unweighted and centerless, so that he feels he could blow away at any time.” Damon is grief stricken: “In this state travel isn’t celebration but a kind of mourning, a way of dissipating yourself.” When he visits Victoria Falls, he notes: “It is incredible to see the volume and power of so much water endlessly dropping into the abyss, but part of him is elsewhere, somewhere higher up and to the right, looking down at an angle not only on the falls but on himself there, among the crowds.”

Damon doesn’t tell this story just from memory but from a specific type of memory rooted in such self-awareness. Hence, again, the use of both first and third person. “What is he looking for,” Damon muses, “he himself doesn’t know. At this remove, his thoughts are lost to me now, and yet I can explain him better than my present self, he is buried under my skin.”

It is on this journey that Damon falls for Jerome, a Swiss man whose beauty is described as “almost shocking.” Their connection and attraction is immediate, and though they remain in contact after their travels, they never move their relationship to the next level. Damon continues to travel, and once, in what is only described as a “strange country, at the edge of strange town,” he sees the lights of a ferris wheel. Galgut writes:

He doesn’t know why, but this scene is like a mirror in which he sees himself. Not his face, or his past, but who he is. He feels a melancholy as soft and colorless as wind, and for the first time since he started traveling he thinks that he would like to stop. Stay in one place, never move again.

Damon does eventually settles in a place three hours from Cape Town, the empty house of friends. Here he takes a temporary respite from the traveling life, and he rather enjoys it. Now the ballast of the familiar that he sheds is not the predictable but the peripatetic; the journey has taken on weight and to stop roaming is freeing. The house becomes familiar to him, and he notes: “a sort of intimacy develops between him and the place, they put out tendrils and grow into each other. . . . and when old dead branches begin to sprout buds and leaves, and then bright bursts of color, he feels as if it’s happening inside himself.” The external world merges with the internal, creating more complicated layers. Damon not only doesn’t feel like a traveler but also finds it difficult “to imagine that he ever thought of himself that way.” He decides to write to Jerome, to tell him about it, but the news he receives back is not good. And with this news everything changes: “everything he knows looks strange and unfamiliar, as if he’s lost in a country he’s never visited before.”

From early on in the book, I was reminded of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being, particularly of Kundera’s line: “what happens but once, might as well not have happened at all. If we have only one life to live, we might as well not have lived at all.” And here Damon echoes yet expands upon this idea:

A journey is a gesture inscribed in space, it vanishes even as it’s made. You go from one place to another place, and on to somewhere else again, and already behind you there is no trace that you were ever there…. Things happen only once and are never repeated, never return. Except in memory.

Except in memory! What this unbearable lightness does not quite consider perhaps is the palpable resonance of memory. And memory takes on quite a weight in In a Strange Room: “What you don’t remember never happened,” Damon thinks. To echo Rimbaud once more, perhaps not only to become a seer does one need a derangement of the senses, but to become a traveler, as aforementioned, and also, to remember. Memory is a derangement of the senses. It is about desire, it is about subjectivity. It is to allow oneself to exist simultaneously in two spaces—past and present—and to allow those spaces to act on each other.

In the third novella Damon travels to India with his good friend Anna, who is “in a bad way,” having arrived with “a small pharmacy in her bag, tranquilizers and mood-stabilizers and anti-depressants.” Damon begins to think of her illness “as a persona separate to Anna,” and he realizes that what is the most dangerous to his friend is inside her, “driving along with so much fury and power.”

In a novel where traveling is seen as existentially bleak, it’s no wonder Anna travels with “the dark other stranger inside her, the one who wants her dead.” We also continue to notice the division of his own self: “Now I’m watching myself move, like somebody who isn’t me.” When Damon realizes that Anna has done something drastic, it’s no surprise that here we see both the third person and first in the same thought, once again: “His body is working by itself, trying to undo what it already accomplished, while his mind and spirit are elsewhere, having a high, disconnected dialogue. What will happen if, if what, if she, no, I don’t want to think about that” [emphasis mine].

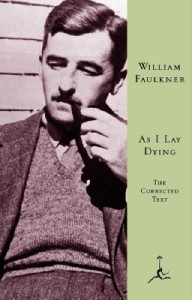

Travel, for Anna, is an active state of dying, made all the more resonant in the context of the book’s title. In a Strange Room comes from Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. It appears, disguised, in the first novella; after wandering around his campsite, Damon sits in the sun to read, and though neither Faulkner nor the title are mentioned herein (though Galgut does attribute the quote to Faulkner in his Acknowledgments), this is what follows: “In a strange room you must empty yourself for sleep. And before you are emptied for sleep, what are you. And when you are emptied for sleep, you are not. And when you are filled with sleep, you never were.” These are the musings of Faulkner’s Darl, within whom is also a powerful duality that lies in the tension between what is said and what is felt; to the external world he appears slow and senseless but his interior landscape is lyrical and articulate.

Travel, for Anna, is an active state of dying, made all the more resonant in the context of the book’s title. In a Strange Room comes from Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. It appears, disguised, in the first novella; after wandering around his campsite, Damon sits in the sun to read, and though neither Faulkner nor the title are mentioned herein (though Galgut does attribute the quote to Faulkner in his Acknowledgments), this is what follows: “In a strange room you must empty yourself for sleep. And before you are emptied for sleep, what are you. And when you are emptied for sleep, you are not. And when you are filled with sleep, you never were.” These are the musings of Faulkner’s Darl, within whom is also a powerful duality that lies in the tension between what is said and what is felt; to the external world he appears slow and senseless but his interior landscape is lyrical and articulate.

In a strange room you must empty yourself for sleep. Perhaps in a strange land you must empty yourself for travel. Whereas earlier in the book, Damon speaks of travel as projecting oneself into an empty place, later it seems it’s the place that requires the traveler’s emptiness. Anna etches herself into her journal. She shits her pants and gets her stomach pumped and sleeps with inappropriate men (despite not really liking men, and despite her female lover back home). She is discarding herself, becoming a shell of the person that she was. After a dramatic episode and its attendant complications, Damon says of Anna: “The high tide of madness has receded, leaving behind this translucent husk of a woman who nearly resembles his old friend. But not quite.” Her identity has shifted.

The first novella begins with Damon feeling “intensely happy” and the last ends with him feeling “awful, but also relieved somehow, emptied out. … The day is wearing on and he has a bus to catch, a journey to complete. It’s time to go.” And then the journey becomes not one of searching, or idling, or waiting, but of escape: “His onward journey is like an endless running away.”

In her Nobel Lecture (December 7, 1991), Nadine Gordimer says: “For myself, I have said that nothing factual that I write or say will be as truthful as my fiction. The life, the opinions, are not the work, for it is in the tension between standing apart and being involved that the imagination transforms both.” And here is the tension of the three novellas; here is the tension in the choice of point of view. Damon’s identity as a writer is acknowledged near the end, further blurring the author–narrator–character divide, when he receives an email from one of the taxi drivers he met during the ordeal with Anna: “I always remember your good words, your words are a great knowledge to me. In future if you publish a book you should write about that girl, who wished to die.” And the alternating point of view is no longer mere artistic choice or a function of the story itself; suddenly, with this delving into yet another layer of Damon the character as Damon the writer, the alternating point of view becomes philosophically brilliant.

Duality mirrors itself. The temporary life begins to feel permanent, the other life becomes more real than the real, and traveling is no longer a state of projection or suspension or derangement but the actual, concrete state of being. By the end of the novel, Damon can no longer be an observer: “In all of this he tries to behave like an ordinary traveler, marveling at what’s around him. But he hardly manages to lose himself, mostly he is stuck in one place in the past.”

The imagination transforms both. As in the heartbreaking reflection at the end of the novel: “Lives leak into each other, the past lays claim to the present. And he feels it now, maybe for the first time, everything that went wrong, all the mess and anguish and disaster. Forgive me, my friend, I tried to hold on, but you fell, you fell.” And there Damon is, both in the first person and the third, both in the past and in the present, his selves real and observed melding into one in a strange yet familiar room.