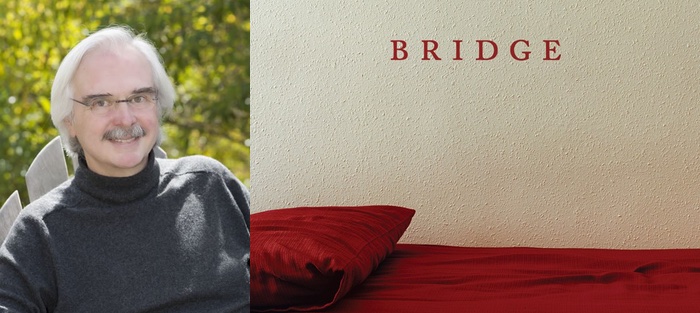

Sometimes the best books are the hardest to categorize. Poetry or prose? Neo-noir or psychological thriller? Robert Thomas’s debut novel, Bridge, published by BOA Editions, was recently awarded the 2015 PEN Center USA Literary Award for Fiction. Bridge came as a complete surprise to me. A poet friend handed me the book without comment, just read this. Some books are a love affair, an infection, a fever dream. Meaning, if any, shifts from reader to reader, from reading to reading. I’m still reading this slim, unassuming novel. I can’t set is aside, shake it off, move on. Written in 56 brief sections that are organized into three parts, Bridge is stunning. It’s a book that I’ve been carrying around with me for a month. Bridge is written from the first person perspective of Alice, a 33-year-old woman who once wanted to be a marine biologist or a dancer, but who now works as a word processor at a San Franciscan law firm. Alice doesn’t explain what happened: we hear snippets about her parents’ one time only visit to the apartment where’s she’s lived for ten and a half years, who bring a salad as a housewarming gift; there’s a reference to when “everything began to go wrong, when I could no longer walk from my room to the library because the trees were growing,” to “voices,” sleeplessness, a history of self-harm—that’s all we know. Whether or not Alice is a little or a lot suicidal, homicidal: she keeps a getaway bag packed, and she’s recently acquired a gun—those are the bare bones of a story where not too much happens. Meaning is derived more from the intensity of language and image and associative connections rather than causality. Robert Thomas and I corresponded recently to talk about Bridge.

Interview:

Lynette D’Amico: You’ve previously published two books of poetry, Door to Door (Fordham University Press), Winner of the 2002 Poets Out Loud Prize, and Dragging the Lake (Carnegie Mellon Poetry Series). Some of the sections in Bridge were previously published as poems— “The Gift” and “Catchy Tunes” were in Poetry—did you originally conceive the project as poetry?

Robert Thomas: I think for me there are really two questions: one is poetry vs. fiction, and the other is poetry vs. prose. It’s actually hard for me to remember how I originally conceived the project, but I know the first draft was prose. That doesn’t necessarily say much about my conception, though, as I’ve often written first drafts of poems in prose. In fact if any poets are suffering from writer’s block, I think one strategy worth a try is writing in prose. I’ve always found prose liberating even if the final version of a piece is in verse.

That said, let me say right from the start that Bridge is based, in part, on experiences I had years ago while working at a law firm. Anyone who worked there at the time would undoubtedly recognize events in the book, and would also recognize that in the book there are some radical departures from the “facts.” So right from the start it was clear in my mind that there was a story to be told. It might be told in poetry or it might be told in a novel or it might be told in a sequence of prose poems, but there was a story—

—and a story that was based on real life events, and clearly a story that took possession of you and mandated its telling.

Yes. When I first submitted the manuscript of Bridge to BOA Editions, the future publisher, I submitted it as poetry and called it “a novel in prose poems.” I also still have a version of the book on my computer entirely in verse couplets, which was a middle version between the original prose draft and the final prose draft, and I suspect the verse version tightened the language. The timing worked out well because by the time Peter Conners, BOA’s publisher, gave me the wonderful call saying he wanted to publish the book, and to treat it as fiction, I’d independently come to the conclusion that the book should simply be thought of as fiction, a short novel, no matter how “poetic” or lyrical a novel it might be.

In general, when poets shift genre it’s to memoir or creative nonfiction (I’m thinking of poets such as Rigoberto González, who wrote Butterfly Boy, Li-Young Lee who wrote The Winged Seed, Paisley Rekdal, author of Intimate: An American Family Photo Album, and Natasha Tretheway, Mark Doty). Why the turn to fiction? As I know your poetry employs many fictional qualities, was it a more or less natural transition, or didn’t it occur to you that you were writing fiction until you were?

As Bridge is partly autobiographical, it certainly could have been written as a memoir, but I don’t think that would have interested me. I always thought of it as something like a sequence of lyrical dramatic monologues. For one thing, although the book is partly autobiographical, I didn’t have an inkling of how it would end until I was maybe two-thirds through the first draft, and it was important to me to keep the book open that way. I didn’t want to know how it would end. I still think it might have ruined the book if I’d known at the start how the story would end, and that’s one reason it needed to be fiction.

As Bridge is partly autobiographical, it certainly could have been written as a memoir, but I don’t think that would have interested me. I always thought of it as something like a sequence of lyrical dramatic monologues. For one thing, although the book is partly autobiographical, I didn’t have an inkling of how it would end until I was maybe two-thirds through the first draft, and it was important to me to keep the book open that way. I didn’t want to know how it would end. I still think it might have ruined the book if I’d known at the start how the story would end, and that’s one reason it needed to be fiction.

A whole other question is how you frame or “wrap” a book when you give it to a reader. If you call it “fiction” or a “novel,” the reader will have different expectations than if the book is called a “memoir” or (horrors) “poetry.” Certainly some readers and lovers of fiction will be disappointed by Bridge because it goes to such a lyrical extreme and arguably would be more honestly described as a sequence of prose poems. Ultimately I decided that would not be a more honest description. Some of the greatest poetry of the 20th century is, for example, the novels of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, but there’s no point in questioning that Ulysses and To the Lighthouse are fiction. A contemporary example would be Michael Ondaatje and a novel like The English Patient, where there are poetic passages of extraordinary lyricism that deepen the emotion and the psychology without necessarily moving the action forward in the traditional way of fiction. Ondaatje is a great example of a writer who “bridges” the genres of poetry and fiction brilliantly.

In a book that is comprised of 56 individual sections, many that could operate as standalone brief lyric essays or prose poems, how was the text assembled? When/how did you know you were writing a book-length narrative? Did you use any particular book/books as a model or stage for Bridge?

I think Bridge has something in common with other lyrical, obsessive novellas like Marguerite Duras’ The Lover or Paul Harding’s Tinkers, but also has some less expected models like Julio Cortázar’s strange book Cronopios and Famas or Camilo José Cela’s even stranger Mrs. Caldwell Speaks to Her Son, a “novel” in the form of brief journal entries that could stand alone as poems. In fact a couple are included in the wonderful Ecco Anthology of International Poetry edited by Ilya Kaminsky and Susan Harris.

Other than the frequent times I doubted Bridge would end up anywhere other than my computer’s recycle bin, I always envisioned it as a full-length book, although possibly a short “poetry length” book. The final order of the sections is very close but not identical to the original order in which they were written, and I also wrote a couple of relatively lengthy new sections (e.g., “10½” and “Voices and Weather”) after the manuscript had been accepted. Probably the most crucial late addition was David’s letter to Alice, which was not in the original draft and which is really the only time in the book we hear David in his own words (while knowing that even that could be a creation of Alice’s mind).

“But then? No then,” wrote Kafka. In a novel with a loaded gun but “no then,” where is the narrative urgency? What propels the reader and narrative forward? And in our new reality where guns are loaded on so many levels, what are the implications of a narrator with a loaded gun? I’m interested in hearing a little bit about where the gun came from—a loaded gun is one part cliché—“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off,” says Chekov, and in our contemporary reality of too many guns and too many shootings, it’s loaded on so many levels. I also assume that you know that research suggests that women are more likely to kill themselves by less immediately lethal means, such as drug overdosing, rather than by using a firearm or other high mortality actions, such as hanging.

Did you go around and around about using a gun in Bridge as Alice’s weapon of choice, so to speak? Did you get pushback from readers about the choice of a gun? Why a woman and a gun?

I know this response is a copout, but the real-life events that inspired the book in fact involved a woman with a gun. I never wavered from the decision that Alice’s weapon would be a gun. On the other hand, I wavered a whole lot about what she would do with it! One of the most rewarding responses I got from a reader was a letter from Eleanor Wilner that was really a prose poem in its own right, and she said she appreciated that I’d violated what she called “Chekhov’s dictum (religiously taught and slavishly followed).”

Personally I am a passionate advocate of gun control, and Bridge could be interpreted as supporting that point of view in the sense that Alice is precisely the kind of person who should and hopefully would be prevented from buying a gun by a background check. At the same time, Alice spends much of the book justifying (or rationalizing) both murder and suicide, and I’d say I wanted to give her her full day in court to make her case.

One other book that I’d mention as a model and an inspiration is, not surprisingly, Camus’ The Stranger (I guess I’m just an old-fashioned existentialist), as well as Camus’ books of essays The Rebel and The Myth of Sisyphus, which I believe Camus described, respectively, as explorations of whether either murder or suicide can ever be justified.

Joshua Ferris, author of And Then We Came to the End, a novel about employees at a Chicago advertising firm, says about work in fiction: “Vocation in literature is never happenstance, never half-hearted decision-making, but artfully premeditated and always purposeful. Work does work in every great book—even if just to allow the characters enough leisure time to pursue the main drama.”

The mundane world of work is not often depicted in fiction outside of Dickens’s law clerks, Melville’s scrivener, or Kafka’s salesman pre-flatbacked bug. In so many fictional worlds of romantic heartbreak and apocalypse, natural, supernatural, and historical disasters, addiction and adultery, how did you come up with a novel about a word processor at a law firm? What can be said about the depiction of work in fiction? Why a word processor? Why a law firm? I know you work as a legal secretary; was the choice of Alice’s profession based on what you know directly from your own work experience?

This question covers a lot of ground! I’ve always been interested in fiction (and even poetry) that includes the work lives, not just the love lives, of the characters, maybe especially when their work lives are mundane. One of my favorite books is Jane Smiley’s The Age of Grief, a great novella that was adapted into a pretty terrible movie, The Secret Lives of Dentists. The book includes a lot of detail on the mundane work of dentists, and I think it helps ground the extreme romantic passion in the book. People often quote Flaubert’s advice to “be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work,” and that may also be good advice within works of art: give your characters regular, orderly lives so they may be violent and original in a credible way.

That said, yes, Bridge takes a lot from my own experiences working in law firms. Like Alice and David, I’ve worked as a word processor, although that job was more common twenty years ago, and I worried a bit about whether it would seem anachronistic. The fact is that their jobs are not very demanding, and that creates time and space for their intense personal relationship, not to mention fantasies, to blossom. As Alice says, “It’s more intense than any marriage. David and I sit in a room together, a room that’s not very large, just the two of us, forty hours a week, with (it’s no secret) little work to do.”

Bridge invokes other art forms as cultural markers throughout the text, including music, literary references, and film. How do references to other kinds of art serve your story? In particular how does opera connect to a mentally ill narrator—why opera and how does that genre/art form enhance the reach of the story?

It’s certainly true that Bridge is perhaps overloaded with cultural markers, from Puccini to Proust. As Alice says in the very first section, there is an “unspoken conversation” between her and David that consists of the books they read: “He’d read American Pastoral or The Corrections at his desk while I read Beloved or Middlesex at mine.” As an unforgivably gross generalization, I’d say there are two kinds of books: those where the main character is as intelligent and as passionately engaged with the world as the author (I think of Anna Wulf in Doris Lessing’s Golden Notebook) and those where the main character is somehow more limited than the author (I think of Rabbit in John Updike’s novels). While I am a huge admirer of Updike (and I know not everyone is), I find the first kind of book tremendously exciting. It was a revelation when I first read Lessing: I didn’t know you could do that! Alice may be an unreliable narrator in some (or many) ways, but in a very real way I want her to be at least as reliable and perceptive as I am.

It occurs to me while talking to you now that opera may simultaneously be the most extroverted art form and appeal to the most introverted art lovers, because it’s one of the most subjective art forms. One could say that even classic opera was expressionistic before expressionism existed, in the sense that its larger-than-life quality struggles to express that, subjectively, life always feels larger than life. Simply talking to someone about one’s experience doesn’t feel adequate. It needs to be sung at top volume, with an orchestra of 100 instruments. One passage in Wagner’s Ring Cycle calls for 18 anvils in the orchestra! Alice can certainly relate to that emotional and psychological extremity.

I love that! I read in an interview with you that the intensity of the monologues in Ingmar Bergman’s film Persona “is the quality I crave most in the novels and stories and poems I read as well as in movies (not to mention my own writing).” Can you say more about what you mean by this “intensity”? Where is it exhibited in fiction you read? Poetry?

It’s probably not a coincidence that the example I gave of intensity was from film. For me nothing is as intense and powerful as a close-up monologue, maybe Liv Ullmann looking straight into the camera and talking quietly, at length, in one of Bergman’s films, or Maggie Smith in Alan Bennett’s Bed Among the Lentils. She almost sounds like Alice from Bridge in parts of Bennett’s dramatic monologue, when she says things like “That’s the thing nobody ever says about God: he has no taste at all.” A third example would be Colm Tóibín’s Testament of Mary, which Tóibín wrote both as a novella and as a dramatic monologue for the stage. I’d love to have seen Fiona Shaw perform it on Broadway—or listen to Meryl Streep’s audiobook version! The question of whether Bridge is poetry or fiction may obscure the fact that, more than anything else, it’s a third genre, a dramatic monologue, and perhaps ideally it would be performed on stage.

I suppose in literature the archetypal example of intensity for me would be Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment or, in a similar vein, Dostoevsky’s Underground Man in his novella Notes From the Underground. Alice explicitly compares herself to Raskolnikov in one passage of Bridge, and one could think of Alice as an Underground Woman.

Can you speak to being a writer outside of the academic world, outside of the “workshop” world. How do you support and sustain your writer identity? Do you ever feel like you’re living in more than one world?

In some ways I feel as if I’ve had the best of both worlds, as I’ve had great, generous teachers in the wonderful MFA program at Warren Wilson College, and I’ve also been in a poetry workshop with friends in the Bay Area that’s been ongoing for 25 years, but it’s true I’ve also kept my distance from the academic world. I don’t envy the many writer friends I have who are struggling to eke out a living with a patchwork of part-time and often low-paying, no-benefit teaching jobs. And it does give me a certain freedom as a writer. I don’t have to worry that the professor down the hall will find my writing wanting if it doesn’t take into account the latest thinking on ontological logopoiesis.

Writing fiction also gave me some freedom because all my “academic” background was in poetry. I’m sure I made mistakes in Bridge that are glaring to anyone who’s taken a Fiction 101 class, but that may not be entirely a bad thing. The weaknesses are real flaws, but my lack of training in “point of view” and other elements of craft may have spared me some inhibitions and self-consciousness that would have caused more serious flaws.

One of my strongest convictions is that it’s our flaws that give us our individuality. Often what makes someone memorable is their unique scars. There are huge flaws in the poetry of Whitman, of Ginsberg, of Plath, of every poet worth reading. And they’re real flaws, not just some unappreciated features of their genius. And yet those flaws are integral to what we treasure about their poetry and what makes it memorable. Toni Morrison and William Faulkner aren’t at their best when they’re perfect, but when Morrison is most herself and Faulkner is most himself. I believe in being a demanding editor of one’s own work, but you have to avoid the temptation to edit out the best stuff, to airbrush the scars.

What are you working on now?

I seem to have gone to the opposite extreme in terms of form, but probably not in terms of content. I’ve been writing a series of sonnets about jealousy (working title: “Sonnets to a Green Screen”). You can read a couple in the Winter 2015 issue of Beloit Poetry Review. To give a sense of why the subject obsesses me, let me quote James Hillman’s for-me-life-changing essay “On Psychological Creativity”: “Of all forms of impossibility, the arrow strikes us into triangles to such an extraordinary extent that this phenomenon must be examined for its creative role in soul-making. … So necessary is the triangular pattern that, even where two exist only for each other, a third will be imagined.”