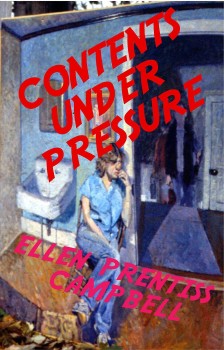

Though Ellen Prentiss Campbell has only been writing seriously since 2001, at age sixty-three she brings a lifetime of experience as a psychotherapist to the marvelously crafted stories in her debut collection, Contents Under Pressure, released in February from Broadkill River Press, and her debut novel, The Bowl with Gold Seams, which Apprentice House will publish in May.

Campbell’s work is as disarmingly understated as she herself: one develops an awareness of the quietly disturbing beauty of her prose as the plots unfold. Stories take hold of the reader with dignified insistence and do not let go. Her characters linger, their problems as real as those of friends one knows from work and life. Always there is the inexplicable confounding of loss and love, but in Campbell’s hands, the circumstances startle us: for example, in the story “Sea Change,” the protagonist, Adrienne, joins a scientific study to become a mermaid, only to meet the perfect human partner soon after she’s slated for ocean life. And in her wistful novel, The Bowl with Gold Seams, only Quaker Hazel Shaw can see past wholesale racial resentment for the Japanese diplomats detained by the State Department at a hotel in Pennsylvania where she works as a secretary. Hazel’s evolving relationship with the imprisoned Harada family becomes a meditation on the mistakes we make in the name of doing the right thing, of love.

Campbell and I first met as classmates at the Bennington Writing Seminars, and so in many ways this interview represents but a sample of the discussion that has been taking place between us—online, in person, and via the phone—for nearly a decade.

Interview:

Susan Scarf Merrell: What happened in your life and/or thinking that led you to begin writing seriously? Or, taking yourself seriously as a writer?

Ellen Prentiss Campbell: I love answering this question. It was a confluence of events, in the world and in life.

They say that memory begins with language. In the beginning was the word… I know that is true for me. I talked early, and my parents—both teachers—read to me. When my own first child was born, my mother told me to read aloud to her whatever I was reading—Dr. Spock, War and Peace—that it didn’t matter and she would hear my voice; I’m sure my own mother had done that for me too, laying down the wiring for reading and writing from the beginning. And by the time I was able to talk, in addition to a bedtime story ritual, my parents let me dictate to them (in more ways than one, my husband Harry would say). I still have the small spiral pad that was my first “journal,” their transcriptions of my dictation according to the prompt: “the best thing that happened today…” or “the worst thing that happened today…”

Once I could read and have a library card, once I could write, the page, the pencil, and pen, were part of me. My family has instructions to bury me with my library card!

I read and wrote my way through elementary school, college, social work school. I fell for George Eliot and Thomas Hardy in a big way in college. But although I never stopped reading, and never stopped writing a diary, and I wrote essays and papers during my academic career, I wasn’t writing fiction. Life had intervened, interrupted. And raising children and practicing as a psychotherapist were further absorbing, diverting, distracting detours.

So what started me writing fiction and seriously considering myself a writer?

So what started me writing fiction and seriously considering myself a writer?

It was 9/11, and the ensuing events in my personal life. I did not have a close, immediate personal loss when the towers went down, when the flight landed in a field not far from my summer home. But for me, as for all of us, there was a new sense of vulnerability and a sharper awareness of how fragile and precarious life is. And then, soon after, my father died. A timely death, not unexpected, but a huge loss and change in the landscape. A few months later, again not unexpected, my mother died. And so the twin towers of my own life went down. Those losses, those reminders of mortality and my changed circumstances (launched or almost launched kids) propelled me into writing, prompted me to tell my stories after thirty years of listening to the stories of others. Remember when April Bernard quoted Ovid in a lecture at Bennington? “Hold nothing back, you cannot take your song with you when you go.” That’s it, in a nutshell.

But to make a short story long, I began writing fiction keenly aware that with the death of my parents, their voices and stories were gone. Short stories first, many set in the region where we have our family summer home, a place full of memories. Then, by chance, or fate, I learned that the beautiful, deteriorating old resort near our summer home had been the unlikely detainment center for the Japanese Ambassador to Germany and his diplomatic staff and their families in the summer of 1945. The episode took hold of my imagination, grabbed me by the throat, demanded that I write about it. As you know—having read countless revisions of the novel—I wrote my story of the intersection of local Pennsylvania hotel staff and the Japanese detainees from multiple points of view until finally one character insisted it was her story. That was Hazel, the young woman working for the State Department’s man in charge.

Afterward, I realized why it became Hazel’s story. It goes back to why I started writing seriously over a decade ago. All stories (even “nonfiction”) are fiction, as they say, influenced inevitably by the teller. And although my novel includes some actual people—the Ambassador, the celebrated Japanese violinist Nejiki Suwa who played a Stradivarius given to her by Goebbels— Hazel is pure fiction. But I began writing the novel at about the same time I was reading through my father’s letters from the war, the letters he’d written to his fiancé, my mother. She’d saved them. Her letters to him? Gone. Although it wasn’t a conscious decision, I now believe Hazel became the point of view character for this story of war on the home front because I regretted, deeply regretted, that my mother’s letters, my mother’s voice, the voices of so many women on the home front, were lost and silent. Hold nothing back, you cannot take your song with you when you go, right?

One of the themes, the central theme perhaps, of The Bowl with Gold Seams is that even that which is broken is beautiful. And Hazel must re-visit the past to move forward. I think beginning to write when I did, seriously, was very much in response to the damage, the breakage in the world and in my life. Writing is a way to put pieces together, to make something new, if we’re lucky, to make something beautiful, out of what’s broken.

Betrayal also seems to be an important theme for you, in the beautiful stories in Contents Under Pressure and also in the subtle wistful elegance of the novel.

Yes, but the real betrayal that is an important theme, the overarching betrayal, is woven into the character’s experience of events and life, I think, even more than being specific interpersonal events. There are lots of those betrayals—affairs, thefts, lies—but the real betrayal they/we wrestle with is the way in which the world of experience surprises us by not fulfilling our assumptions and expectations of how life should be. That feeling of this wasn’t what I signed up for when something unexpected happens: a loss, a failure. Yes, people betray each other, but we also betray ourselves. My character Lily, for example, discovers her husband’s infidelity, but also discovers that she has been blind; she has failed to protect herself. And she resolves, believes, she can protect her child. We can imagine how imperfectly that will work out beyond the end of the story.

Your stories are meticulous in their structure, as is the novel. Can you speak a little about your process, about your technical planning?

You know, it’s not so much technical planning as something akin to my understanding of what the Quakers would call continuing revelation, an ongoing, continuous process of discerning. With both a story and this novel (and my two novels in progress), something flying around in the ether smashed into my dashboard and demanded my attention. It’s that odd alchemy: past, the present intersect, the real and the imagined.

In terms of structure, it’s unusual for me to have an entire arc plotted out; rather I start and see what unfolds. But although I don’t do a great deal of advance technical planning, I am a huge reviser once I’ve got a rough draft down, or even as I’m putting it down (though I try to keep going, remembering your adage about touching the end of the pool). The language, the words, the sentences—I really love the process of putting the words together, taking the words apart, putting the words together again. I’ve never put rocks into one of those tumblers to polish them and turn them into jewelry, but maybe writing a story is a little like that.

The novel was different—it reminded me more of knitting a sweater, which I have done, but not much really since I started writing. You start, you hope you have enough yarn, you hope all the pieces fit together, but once you’re into the work it just becomes part of you and it waits there waiting for you to pick it up and continue. I love that feeling of something in progress, something to go back to, to keep working on. And reading the work aloud, after it’s on the page, that’s so important to the process and the product. And I love research. Learning about the backstory, the details… isn’t it funny how the characters teach the writer about the world? When I was a kid I loved to play dollhouse. To arrange and re-arrange the furniture, “my people.” It’s the power. But I also loved all the stories about what happened at night when we were asleep and the dolls were living their lives. A good day of writing is like that. The delicious narrative freedom of being in charge of the universe, and then the universe we’ve created takes over.

I wonder what you think about entering the writing life in a formal way as a more mature person. Do you have advice for younger writers, things you wish you’d done? And do you think you’ve encountered difficulties or advantages—or both!—from the timing of your writing career?

I started writing fiction seriously only a decade and a half ago. But came to it with a sense of this is exactly what I should be doing, this is what I must be doing. Writing now is by way of returning to or finding a true self, a kind of transformation but not so much a re-invention as a recognition, an awareness that all this time I have been one of those people on whom, as Henry James said (was it James, speaking about Edith Wharton?) on whom nothing is lost. One of the things about life, all kinds of experiences in life but perhaps I am thinking particularly about family life, parenting, and marriage here, is that we often have to learn so much to do what is necessary, or try to, at one particular moment in time for a person, or people, we love. And then… what do we do with this hard-gained experience, with what we’ve learned? So much of life is unique, and so inevitably much of what we learn to master is not really re-usable. Or at least it feels that way as the next dilemma, the next wonderful terrible thing, happens.

I started writing fiction seriously only a decade and a half ago. But came to it with a sense of this is exactly what I should be doing, this is what I must be doing. Writing now is by way of returning to or finding a true self, a kind of transformation but not so much a re-invention as a recognition, an awareness that all this time I have been one of those people on whom, as Henry James said (was it James, speaking about Edith Wharton?) on whom nothing is lost. One of the things about life, all kinds of experiences in life but perhaps I am thinking particularly about family life, parenting, and marriage here, is that we often have to learn so much to do what is necessary, or try to, at one particular moment in time for a person, or people, we love. And then… what do we do with this hard-gained experience, with what we’ve learned? So much of life is unique, and so inevitably much of what we learn to master is not really re-usable. Or at least it feels that way as the next dilemma, the next wonderful terrible thing, happens.

I suppose in part that is where the beauty of writing fiction, and developing as a writer at this time, comes in. You know, I had been listening to others tell their stories of struggle and pain and joy and sadness for many years as a psychotherapist before I began writing. And I’d been living my own stories all those years. All stories are fiction, how deeply I believe that. All narrators, each and every one of us, are unreliable. But there’s a way in which having been on life’s journey for a while (how lucky to have had this time, these experiences) changes your perspective, your angle of vision. More and more, as a writer, as a person, as a psychotherapist, I find myself traveling in this deep inner space. Free-er to zoom in and zoom out.

And although I wasn’t writing fiction, wasn’t writing seriously, I was writing every day. I am grateful for that. I think for me it is necessary to write and to read, absolutely necessary. I have kept a journal since before I could write, when my parents let me dictate to them each night the best or worst thing that happened that day. But in the most intense seasons of parenting and working I could barely keep up with keeping a journal. Months would go by between entries. I did write a few words almost every day in my day-planner though. And I’m convinced that committing some fragment of observation to paper in that incredibly cursory shorthand way helps me now as a writer access memories. Not by going back and reading the hard copy—it’s gone. But I believe the incredible neurological alchemical process of observing, noting, and writing crystallizes memories. So if I were speaking to a young writer I’d say be sure to keep the habit of watching and writing going. They say memory is tied to language acquisition. Well, clearly language is key. But I also think making sense of the world, patterns of the world, is for me tied to taking in experience and then trying to transcribe it.

Have you ever seen a marathon race? I’ve only seen one, when my youngest daughter was competing. What struck me, amused me, horrified me, was that the age category is written right on the runner’s thigh. Well, in a way, that’s true for all of us as writers, too. Young women competing in cross-country races are often fastest when they are still more girl than woman—a sleeker, slimmer body, more aerodynamic. Well, perhaps it’s a bit like that in writing, too. Writing is a marathon for sure. And a brilliant young writer just seems to be an incredible blazing force. It’s thrilling and wonderful to think of all the years and miles the young writer has ahead of her. And of course I regret that starting out late means I have less time. But of course that’s also what makes this the time for me to be writing. Now is absolutely the time to be writing, to hold nothing back. Sure, sometimes I feel sad that I could have written so much more if I had started sooner. But I couldn’t have written what I’m writing now, then. Not because I’m seasoned or mature or wise but just because every lived moment is part of what informs writing in some mysterious way.

So, in writing, we draw on both lived experience and imagined experience. But the mixture—the proportion of memory to imagination—that’s not a function of age. It’s just a matter of finding the right balance of ingredients at the moment. According to the cake mix box, when you bake at high altitude, it takes longer. Maybe I’ve been cooking these stories, these fictions, all along—it’s just taking the time it needs to.