Of Limitless, one of Horse Heaven’s (2000) thoroughbred stars, Jane Smiley writes:

Like every genius, and he was a genius, as his race record would eventually prove, he had not so much a plan as a specific, overriding aim. His nature was out of balance in this way, whether through brain chemistry or as result of organization of the nervous system as a whole. His aim was to run. And he was in luck. Not only did he mean to run, he could run; perhaps, though, the cause and effect were reversed—he could run, and so he meant to run. The feedback loop hummed endlessly—he could, he did, he wanted to, and he could. For him, as for all geniuses, the aim was insistent, the prompt was immediate and strong.

When I first read Horse Heaven, I didn’t yet know what I now trust to be true: Jane Smiley writes novels the way Limitless runs. That is, tenaciously, with joy and verve, to great acclaim. Smiley’s prose—the easy cadence of her sentences, the detailed embodiment of each character, the fullness of her scenes—reads as effortless, not for lack of effort but because on the page we find Smiley, like Limitless, “in the state of relief that comes from doing all the time what it is that you aim to do.”

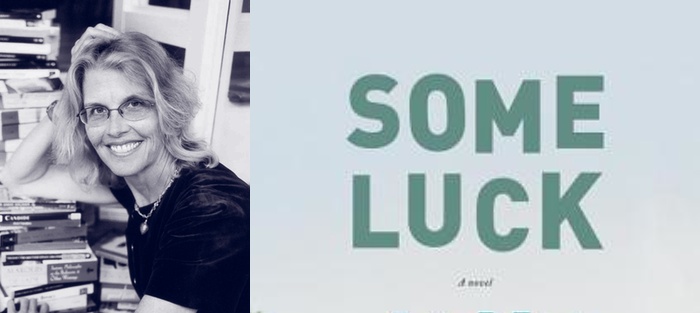

Smiley has written over twenty books—novels, a short story collection, nonfiction, and young adult fiction. Her novel A Thousand Acres (1991) received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1992. In Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel (2005), Smiley writes with enthusiasm and expertise—as both historian and craftswoman—on the origins of the novel, the process of writing “a novel of your own,” and, in review-like short essays at the back of the book, on 100 great novels. Some Luck, the first installment of Smiley’s forthcoming trilogy The Last Hundred Years, will be published by Knopf in October of 2014.

I met Jane Smiley when she was in Ann Arbor as the Zell Distinguished Writer in Residence at the University of Michigan. We spoke in the sunny lobby of her hotel. She drank a Diet Coke, fiddled with an unwrapped Werther’s Original, and answered my questions about the evolution of her writing life with generosity and consideration.

During our conversation, Smiley set herself apart from the kinds of writers who “just go by instinct, go by instinct, go by instinct,” but I beg to differ: Jane Smiley writes by instinct, only her particular brand of instinct compels her towards the unknown—new challenges, new genres. Her instincts serve to ward off boredom and repetition for writer and reader alike. And these impulses—coupled with her stubborn, assured, and inquisitive writerly temperament—result in the diverse, wildly fun, surprising, and energetic body of work she has accumulated over the course of her prolific career.

Interview:

Mary Camille Beckman: I recently read a piece in the New York Times that asked, “Is it harder to write about happiness than its opposite?” This writer said that “happiness threatens the things that every writing workshop demands: suspense, conflict, desire.” Do you find it hard to write about happiness?

Jane Smiley: Most people have some kind of natural inborn temperament and that dictates what they find most congenial to write about, I think. But if you really want to have a long and productive career, you have to work against your temperament a little bit and learn to do the things that you don’t start out knowing. For example, Dickens didn’t have a very organized temperament. He was great with language and sensation and character, but he wasn’t very good at organizing the plot. So when he was about thirty, thereabouts, thirty-two—after [The Life and Times of] Martin Chuzzlewit and before Dombey and Son—he made up his mind that he was going to learn to get organized. There are other writers who are great at plotting, but their characters are totally stiff because they don’t have any innate interest in psychology.

I would say I have a basically sunny personality, so it’s not hard for me to write about happiness. I think it’s easier for a happy person to learn to write about unhappiness than it is for an unhappy person to learn to write about happiness. Because all people experience unhappiness. Not everybody experiences happiness. One of my favorite writers is Anthony Trollope, and he was a very self-motivated and positive person, and he’s quite good at writing about unhappiness, but he’s also quite good at writing about happiness. Some of his fellow writers of the time—like Thackeray, for example—they’re not very good at writing about happiness. The ones who write about unhappiness generally get more respect than the ones who write about the whole range of feelings.

You mentioned that writers have to attack those things they’re not naturally good at—can you share some stories about your own learning? Stuff you weren’t good at?

I can and I can’t. In some ways you don’t know what you’re not good at. But I do know that my first three novels—Barn Blind (1980), Paradise Gate (1981), and Duplicate Keys (1984)—I knew they were practice.

When did you know?

While I was doing them.

For Barn Blind, I knew that I had to learn how to organize the six or seven characters in the family. I remember making myself a chart and then charting as I wrote, charting their ups and downs in relationship to one another and putting it up behind the stove and at night when I was cooking I would look at it.

And pray for no grease fires.

I didn’t care! [Laughter.]

And then At Paradise Gate, I knew that I wanted to write about a different kind of family. I wanted to write about a death in a family. I wanted to have a different kind of elegiac feeling.

In Duplicate Keys, I knew that I wanted to learn how to make a plot because the other two hadn’t really had plots. So I decided to write a murder mystery. [A murder mystery] absolutely has to have a plot. You have to learn how to divulge bits of information without divulging too much information. I had three people who read it chapter by chapter and they would tell me what they thought was going on at the end of each chapter. And then if somebody seemed to know too much—and there was one person I remember who was much more with it than the other two—I’d fix that chapter so that I hadn’t given myself away.

In Duplicate Keys, I knew that I wanted to learn how to make a plot because the other two hadn’t really had plots. So I decided to write a murder mystery. [A murder mystery] absolutely has to have a plot. You have to learn how to divulge bits of information without divulging too much information. I had three people who read it chapter by chapter and they would tell me what they thought was going on at the end of each chapter. And then if somebody seemed to know too much—and there was one person I remember who was much more with it than the other two—I’d fix that chapter so that I hadn’t given myself away.

For me, a lot of it was conscious learning about how to do some things. That’s the way I have always gone about things. That isn’t necessarily the way that everybody does it. You know, some people just go by instinct, go by instinct, go by instinct, and they luck out. And other people don’t. It has a lot to do with temperament.

Which of your novels have gone through the most drafting?

Private Life (2010) was the most.

How many drafts?

Well, I think officially maybe five. Guess which one went through the least?

Horse Heaven? [Interviewer’s note: In Thirteen Ways, Smiley writes, “When I think of all my novels, I imagine them spatially, grouped around me on a dark plain….Horse Heaven is large, the closest to me, within arm’s length.”]

No. The Greenlanders (1988).

Really? Why do you think that is?

From reading the Icelandic Sagas, and also certain novels, Nordic novels like those of Sigrid Undset. The language was really in my head. I rewrote the first fifty pages several times. And that was like the beginning of the concerto, you know, when you’re getting into that world. And then after that it was really much more like going, sitting down in front of my computer, putting my bearskin rug on, and just being taken into the world and the language. It felt like I was being spoken to from afar, by the characters and their world. “Thank you for resurrecting us. We have a story to tell.” It was a very uncanny experience.

Have you had that experience since?

No. And I vowed never to have it again.

Do you think it’s something you could recreate even if you tried?

Every novel’s different, but I didn’t want to have that experience again. When I was finishing The Greenlanders, I would get up thinking I’d been sitting at the desk for two hours and I’d written twenty pages. I’d been there for ten hours. I would be sitting there typing, typing, typing and saying, “Die, die, die.”

It was very much like a dream. And I didn’t like it. But, you know, the result was worth it. But I didn’t want to do it again.

In Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel you write about “spit the bit,” the phrase that inspired the novel Horse Heaven:

I conceived the book before I knew anything about the subject. A phrase I heard on the radio, “spit the bit,” suggested to me that the language of horse racing must be wonderfully rich. As I began to learn about racing, each phrase or descriptor I then discovered added its own bit of inspiration to my original idea….[T]he catalyst was language.

I was really surprised that such a small turn of phrase could trigger something as large and expansive as a novel.

Well, that was really true of Dickens. That’s how Dickens started. In his late teen years, he learned to do shorthand. So he got himself a job—and I think it was for a newspaper—where he would go to parliament every night and write down the speeches. And because he was writing them down, he became very sensitive to how people express themselves. So then he started writing little short pieces. He had a lifelong habit of walking around London eavesdropping on people walking past him and because (a) the dialects of England are so specific and (b) London was becoming such a mix of all different types of people, he was hearing very individual ways of self-expression, and he knew how to remember them and reproduce them. So it was language that gave him his original motivation to write books.

What was the catalyst for your forthcoming trilogy?

I don’t know. I think it was the title of the trilogy. I remember sitting with a friend of mine at a fancy restaurant at the Beverly-Wilshire Hotel. He’s a lawyer but also a writer, and I turned to him and I said, “You know, I think I want to write a trilogy called The Last Hundred Years.” And he said, “Don’t tell anybody that title because someone will steal it.”

Did you keep it secret?

I did. I did. For a while, anyway. Until we could show it around.

How is writing a trilogy different from writing a single volume?

It’s pretty much more unwieldy. There are a lot of people to kill off and there are also a lot of people to forget. I mean, you can see why sometimes a trilogy ends up as a hexalogy. You can see why Proust ended up with seven volumes when he really thought he was only going to have three. Because the more people that you introduce then the more unwieldy it gets. I knew it was only going to be a trilogy. It could only be a trilogy. So, I guess the hardest part was cutting off characters that I actually liked. Being willing to ignore certain characters even though I liked them.

It’s pretty much more unwieldy. There are a lot of people to kill off and there are also a lot of people to forget. I mean, you can see why sometimes a trilogy ends up as a hexalogy. You can see why Proust ended up with seven volumes when he really thought he was only going to have three. Because the more people that you introduce then the more unwieldy it gets. I knew it was only going to be a trilogy. It could only be a trilogy. So, I guess the hardest part was cutting off characters that I actually liked. Being willing to ignore certain characters even though I liked them.

Every book offers its own dilemmas and you just have to solve them. That’s just the way it is.

You have to learn how to do it every time.

If you didn’t have to learn how to do it every time, then you would farm it out to a group of hacks who would do it for you.

There’s some guy, some thriller writer—I can’t remember who it is now—but he has been very successful, and after about volume five, he said, “I can’t do this anymore! It’s so boring.” But they wouldn’t let him stop because he was making so much money. If you’re a person who tries new things all the time, sometimes you’re frustrated, but you’re never bored.