On more than one occasion, I’ve heard Steve Almond refer to himself as “a cult writer.” This puts me in mind of some enduring “cult” brands, like Apple and the Mazda Miata, in which people clamor to create a culture around them, evangelizing their merits. It wouldn’t be farfetched to say that Almond’s loyal following of readers would see him as vital to our book culture, with books of equal parts humor and heart, work that resonates on both a personal and cultural level. Those who know his work can hardly help spreading the love of it.

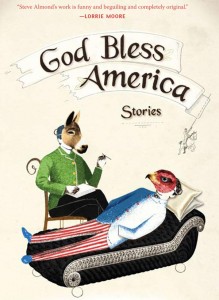

Almond’s books include three collections of short stories: My Life in Heavy Metal, The Evil BB Chow and Other Stories, God Bless America; three works of nonfiction: CandyFreak: A Journey Through the Chocolate Underbelly of America, (Not That You Asked), Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life; and three DIY books: Letters From People Who Hate Me, Bad Poetry and This Won’t Take But a Minute, Honey. He lives outside of Boston with his wife and children.

Over the years I’ve gotten to know Almond, both as a frequent reviewer of his books as well as his time as a faculty member at the West Virginia Writers’ Workshop, where I serve as the Assistant to the Director. Always generous with his time and attention, I reconnected with Almond via email, discussing everything from good editors to exposing unbearable feelings. Almond again revealed his indelible candor and charm through his thoughts on life and literature.

Interview:

Renée Nicholson: When your latest collection of short stories, God Bless America came out in fall of 2011, I listened to several podcasts and read the interviews. One thing that stood out was your unflagging praise for your editor at Lookout Books. Can you elaborate a bit on that relationship?

Steve Almond: Editing, like writing, is an act of sustained attention. A good editor should articulate what they think you’re trying to do with your work, where you’re succeeding, and where you can do better. They should do this not just in larger ways (thematic, structural), but in their line edits. This hardly ever happens in corporate publishing. I was fortunate enough to have Ben George as an editor, and he went over every word I wrote and offered his best advice. After half a dozen edits, it was clear to me what a gift this was. So I spent months editing stories (all of which had been published), and made them much stronger. That’s all a writer should care about: finding an editor who can help them make their book better.

Can you also tell us a little bit about what you’ve been doing in terms of the book—readings, etc.—and the kind of reception the book has received?

I did a bunch of readings in Boston and the Carolinas for GBA, mostly because I love reading and Lookout got a grant, so I didn’t have to go in debt to do ‘em. The book got a few kind reviews, and won the Paterson Fiction Prize, but it’s been a pretty limited release—which is fine. What matters is whether the book will be around in ten years, or ten decades, not ten weeks. History tends to sniff out the phonies.

In many of the stories in God Bless America it feels like the truth is that the American Dream has been lost. Many of the stories read like love letters to that lost dream. Are you concerned about the fate of America, and how does this get distilled so subtly into stories?

In many of the stories in God Bless America it feels like the truth is that the American Dream has been lost. Many of the stories read like love letters to that lost dream. Are you concerned about the fate of America, and how does this get distilled so subtly into stories?

Oh, I’m totally freaked out about America: fearful that we’re headed for ruin, but stubbornly hopeful that we might still locate our better angels. That’s just what I’m constantly feeling, and it gets filtered into all my characters. In my non-fiction, I address this stuff in a concerted way. With fiction, it’s more unconscious. The reason there are two stories about veterans in GBA isn’t because I’m a veteran, or because I know so many veterans. It’s just a function of being alive in this historical moment.

How do you build empathy for characters that are less than likable? I’m thinking of Billy Clamm, the protagonist of “God Bless America,” – a bit of a drifter, a loser, who makes a compelling yet ethically-suspect final decision, or Dr. Oss, the protagonist of “Donkey Greedy, Donkey Gets Punched,” who is not only arrogant, but a gambler, too.

I don’t want readers to approve of my characters. I want them to feel implicated by them. A guy like Billy Clamm represents anyone whose dreams outstrip their possibilities, just as Dr. Oss is a guy who can’t face the truth of his own compulsions. It’s the weakness that makes these characters human, and makes me love them. The reader isn’t meant to exonerate Humbert Humbert. But they inevitably recognize his crisis: loving the wrong person for the wrong reasons.

Across your three books of short stories, you often force your protagonist up against his/her deepest fears or desires. Do you find that there’s resistance to this kind of exposure?

Literary writers, no matter how refined, are always seeking to express unbearable feelings. At least the ones I’m interested in. And that means exposing those feelings to the world, whether in fictional disguise or not. My work only got interesting when I started exposing myself on the page, dealing in radical truths.

Literary writers, no matter how refined, are always seeking to express unbearable feelings. At least the ones I’m interested in. And that means exposing those feelings to the world, whether in fictional disguise or not. My work only got interesting when I started exposing myself on the page, dealing in radical truths.

How do Facebook, Twitter or other social media, which seems to be so much about persona-building and public image, hinder a writer’s ability to get at those radical truths?

I can only speak for myself, but all the social media has made me more narcissistic, more needy, less attentive, less present in the world. I do think it’s a cover-up most of the time, a way of keeping loneliness at bay that somehow makes us lonelier—or me, anyway. There are a number of young writers whose work strikes me as emotionally stunted and awkward, and [shows] a general loss of faith in traditional storytelling.

I’d like to propose a more outlandish claim—your work has a great resonance with Jane Austen, particularly her preoccupation with finding a good match. Are there basic human desires that writers fixate on, and if so, what are some of them?

Jane Austen is one of my favorite writers, and I’m constantly blabbing about how great she is, in part because she explored a single basic question: how do we find enduring love. Her answer was generally that the two people involved have to be able to see one another’s blind spots and help each other. That’s what’s happening in some of my stories, though in others, of course, it’s just the opposite. But the basic question is the same: how do we find love. Readers come to all stories asking the same two basic questions: 1. Who do I care about? and 2. What do they care about? The sooner the author answers these questions, and the deeper the protagonist’s desires run, the happier the reader is. At least this reader.

Which past or present writers do you feel a literary kinship with?

I love my pal Billy Giraldi’s work. It’s so exciting. I’m a great admirer of Lorrie Moore, George Saunders, Jess Walter, Aimee Bender, Tony Doerr. I’m not as good as those folks, but I love the humanity and comic forgiveness of their work.

You’re a writer who is busy—you teach at workshops, you write columns, etc., and schedule a fair amount of readings. How do you balance these activities?

I don’t balance them. I’m just overbooked and crazed and I wind up not working on my serious novels or stories as much as I should. I’m hoping when the kids are older I’ll have more time and, perhaps, more patience. We’ll see.

With books that are on large New York presses, smaller presses, and three self-published books, what have these experiences taught you about how a book comes into being?

The marriage between an artist and a corporation is inherently unnatural. Each party has different ultimate motives. There are happy instances where there’s overlap, but my experience has been that you inevitably feel the dank breath of the home office. So I just got sick of that. Plus, I had these strange little idiosyncratic projects that just felt too personal to seek out the help of a corporation. So I worked with my pal Brain Stauffer, who’s a remarkable artist, and we did it DIY. Obviously, I don’t recommend DIY stuff for folks who think it’s gonna be easy and fun. It’s a lot of work to assume all the duties of publisher. But for certain projects, it makes sense, at least for me. The books feel more like artifacts than commodities.

The marriage between an artist and a corporation is inherently unnatural. Each party has different ultimate motives. There are happy instances where there’s overlap, but my experience has been that you inevitably feel the dank breath of the home office. So I just got sick of that. Plus, I had these strange little idiosyncratic projects that just felt too personal to seek out the help of a corporation. So I worked with my pal Brain Stauffer, who’s a remarkable artist, and we did it DIY. Obviously, I don’t recommend DIY stuff for folks who think it’s gonna be easy and fun. It’s a lot of work to assume all the duties of publisher. But for certain projects, it makes sense, at least for me. The books feel more like artifacts than commodities.

You’ve said that writer should write about the things that they can’t get rid of by any other means. What are those things for you right now?

I’m always at work on one or more failing novels. And in the meantime, I’m totally obsessed with the election, and whether we’re going to march down the path to ruin, or start to behave with more humility and common sense. So I’ve been doing a lot of political stuff at the moment, or “moral” stuff, or whatever you’d call it. I can’t help myself. I’m a failed prophet at heart.

Further Links & Resources

- Steve Almond on why he writes short stories, from MobyLives.

- Read Almond’s writing on The Rumpus.

- Almond’s opinion pieces and articles on Salon—from Soul Coughing to a boycott of text messaging.