Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

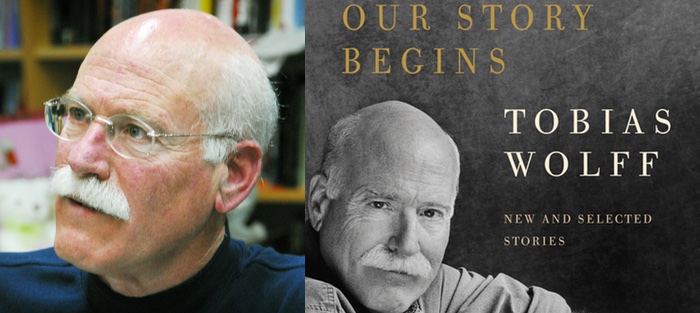

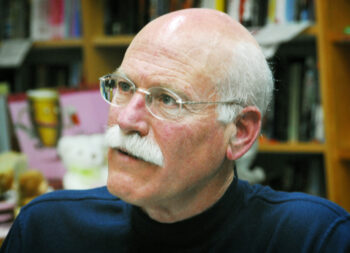

In today’s feature, Travis Holland sits down with literary luminary and master of the short story Tobias Wolff. This interview was originally published on April 5, 2009.

Often heralded as one of America’s great contemporary short story writers, Tobias Wolff is the author of several celebrated collections, including In the Garden of the North American Martyrs and The Night in Question, and his fiction has been widely anthologized. A frequent contributor to the New Yorker, and a recipient of the prestigious Rea Award for the Short Story and the PEN/Malamud Award, Wolff is also the author of the best-selling memoirs This Boy’s Life and In Pharaoh’s Army. His novel Old School was a finalist for the Pen/Faulkner Award. His latest book, Our Story Begins, brings together some of his best-known work with a number of newer stories, in a collection Marianne Wiggins, writing on the front page of the Los Angeles Times Book Review, neatly summed up this way: “A volume that belongs on everybody’s shelf along with Hemingway’s In Our Time, Salinger’s Nine Stories, and the collected works of Flannery O’Connor…” Wolff is currently the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University. The following interview was conducted on January 20th, 2009, in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Interview:

Travis Holland: So I thought we might start off talking about your novel Old School, which I loved. In that novel we get a portrait of the artist as a young man—a very young man. Earnest, idealistic, silly even. And principally idealizing the “greats,” writers like Hemingway, Ayn Rand, Frost. In fact, the young writers in your novel seem to not only idealize them but they want to be them. They want to write like them, they want to be famous. They seem to see that this is the path of the writer. This is what a writer is: the public Hemingway, the public persona of an Ayn Rand or Frost. And I wonder if most writers start out like this, with this idealization of writers and writing.

Tobias Wolff: It seems to me that literary writers aren’t the celebrities they were in those days. Obviously, there are a lot of writers who are celebrities to the young, but I would say by and large they aren’t the kinds of writers that Frost and Hemingway were. In those days the culture was definitely more literary, and Hemingway was an international celebrity, often in newspapers and weekly news magazines—showing him on his boat or in the hills with a rifle. And Frost—to speak on Inauguration Day, as we are doing—was famous enough that President Kennedy wanted him to read a poem at his inauguration. I think that was unprecedented. That was the kind of celebrity, the kind of figure, Frost was. And indeed, even in his 80s, Frost went to Russia and debated with Khrushchev over ideology. These were very, very public figures. Ayn Rand testified before Congress, arguing against any tendency of the United States to go in a collectivist direction. I can’t think of any writer who enjoys that kind of stature today—not because the writing isn’t good enough. It’s because the culture has changed.

Tobias Wolff: It seems to me that literary writers aren’t the celebrities they were in those days. Obviously, there are a lot of writers who are celebrities to the young, but I would say by and large they aren’t the kinds of writers that Frost and Hemingway were. In those days the culture was definitely more literary, and Hemingway was an international celebrity, often in newspapers and weekly news magazines—showing him on his boat or in the hills with a rifle. And Frost—to speak on Inauguration Day, as we are doing—was famous enough that President Kennedy wanted him to read a poem at his inauguration. I think that was unprecedented. That was the kind of celebrity, the kind of figure, Frost was. And indeed, even in his 80s, Frost went to Russia and debated with Khrushchev over ideology. These were very, very public figures. Ayn Rand testified before Congress, arguing against any tendency of the United States to go in a collectivist direction. I can’t think of any writer who enjoys that kind of stature today—not because the writing isn’t good enough. It’s because the culture has changed.

It’s almost as if these young writers, these boys, in your novel were in a way writing in order to be Hemingway, rather than writing to be a writer.

Yes, because the personalities of these writers, their personae, figured so largely in the publicity around them that there was some confusion that this is what it meant to be a writer – to be famous and cut a figure. And maybe the idea of actually doing the work got lost a little bit. When you did see those pictures of Hemingway—fishing, hunting, at war—you forgot that this was just what he was doing when he wasn’t writing. And that, in fact, this was a guy who spent hours every day at his stand-up desk—you know he wrote standing up because his back was so bad. Frost was an absolute workhorse, and so in her way was Ayn Rand, though she’s not to my mind anything like the writers they were, but a very, very popular writer among the young, then and now. And certainly I thought she was fantastic when I was sixteen, seventeen. So, absolutely, the whole idea of the writing life tended to eclipse the actual understanding of what it meant to produce work. That was the discovery you had to make. And I think it was discouraging to many of those who thought that they would be writers. I imagine that once they got into the process of doing it, they realized, “Oh, in order to be a writer I have to actually write. And be obscure for many, many years, and be grateful if I get contributors’ copies from some little magazine.” And this is actually what the writer’s life is like for most of us, for many years. The actualities of that life caught up with a lot of us who were mainly ambitious for the gifts that a successful writer’s life could bring.

Well, the novel seems like such a perfect picture of the evolution of a young writer from this idealistic, or falsely idealizing, notion of wanting to be a writer because you want to be Hemingway, or you want to be famous. We see these young men wanting to be writers—and then what’s left, after this notion of “greatness” falls away. And what we’re left with is a story. The story at the end of Old School, “Master.” And it seems to me a statement about, in the end, what is important. To the writer, and to the work. It’s the work itself, this story about a very simple man.

Yes.

I wondered why you called this section of the novel “Master.”

It’s a double-edged title. Of course the section just before this ends with the word “masters.” The narrator’s listening to his teachers in the headmaster’s house. “These sure and finished men, our masters.” That’s his vision of them. And then he writes something called “Master,” and what we read is a story of a very unsure man, who’s unfinished and full of self-doubt, and self-recrimination for allowing a certain misunderstanding to persist, one that he continues to profit by. It’s also the narrator’s own story of himself. What writers do is they tell their own story constantly through other people’s stories. They imagine other people, and those other people are carrying the burden of their struggles, their questions about themselves. We’ve never actually seen the narrator write a story in this whole book. He can’t know from the brief conversation he’s had with the headmaster all the things he tells us about Makepeace. How would he know what the weather was like when Makepeace goes for a job interview at this military academy? So it’s clearly coming from the narrator. And suddenly he’s giving us a story that he’s written, and the story at its heart is about duplicity and the willing tolerance of peoples’ misunderstanding of him, which the narrator himself has been guilty of. And it’s about estrangement, a feeling of not being home and struggling to get home in some way. So those concerns all come together for me in this end piece. Some people have said, “What’s that all about? Why didn’t the narrator finish his own story?” I was surprised when people had that response, because I thought that it would be apparent that the narrator was really telling his own story.

In your short story collection Our Story Begins, in the introduction, you speak of the “actual, now vanished writer that you were,” when talking about whether or not you were going to revise these early stories. And it made me think of the writer that you were, that “vanished writer” you speak of, when you wrote a story like “In the Garden of the North American Martyrs” and the writer you see yourself as now. I wonder if you can speak about going back and looking at those early stories.

Well, I like that story a lot still. And I’m in sympathy with it and what it says. I don’t know that I could actually write that story now, though. I don’t know why. None of us are the same after 30 years, and I wrote this 30 years ago. I’m not good at saying how I’ve changed, though. I’m not good at seeing what the difference is. I think the readers of these stories probably have a better grasp of the difference between my early stories and the later ones, because I’m always inside myself—you know, it’s hard to step out. I guess reading these stories from a distance of years is one way to do it. But it’s hard for me to put a name to what kind of change has occurred in those years.

Well, I like that story a lot still. And I’m in sympathy with it and what it says. I don’t know that I could actually write that story now, though. I don’t know why. None of us are the same after 30 years, and I wrote this 30 years ago. I’m not good at saying how I’ve changed, though. I’m not good at seeing what the difference is. I think the readers of these stories probably have a better grasp of the difference between my early stories and the later ones, because I’m always inside myself—you know, it’s hard to step out. I guess reading these stories from a distance of years is one way to do it. But it’s hard for me to put a name to what kind of change has occurred in those years.

You’re simply writing from a different place now.

Yeah. I had a certain black humor in those days that flashes a little less often now in my work, or so momentarily that it isn’t so much a feature of the work. Some of my earlier stories—“Hunters in the Snow” or “Next Door”—when I read them, people laugh, and then they’ll come up and say, “Ah, I didn’t realize it was so funny, until you started reading it.” I don’t know what to attribute that to. Some shift in my angle of vision. I’m not sure exactly where it is—it isn’t that I don’t have a black sense of humor. But it does show up a little less often in the work, I think. As I look back on these stories, I do begin to see an obsessive attention to questions of identity, and confusions of identity. Questions of authenticity—how do human beings become authentic? What does it mean to be true to yourself, as Polonius famously tells his son? I see those sorts of questions recurring in the work more and more as time goes on.

Speaking of black humor, it makes me think of “Bullet in the Brain.” What sort of response did you get from that story? Because here’s a story about a critic who can’t stop that critical capacity. We find out that he’s actually a very bitter person—there’s a wonderful line about how, at a certain point, Anders began to despise writers for writing the books he had to read. And I wondered where that story came from.

Well, I didn’t have a particular critic in mind…

[Laughter] I won’t ask.

I’m sure certain critics maybe thought I had them in mind. But actually the horrible truth is that I was mining some tendencies of my own in that story. To be derisory of things that I’d read or hear. It’s a faculty that most writers have—they’re very attentive to the way other people use language. And often I think that I would, without meaning to, have a kind of inward sneer. And to live that way detaches you from reality, and that’s what happens to Anders in the story. The gun isn’t even real to him—it tickles like a finger. His critical faculties have so overwhelmed him that he’s completely detached from reality at the end.

He’s actually critiquing these men, saying they sound like characters from Hemingway’s story “The Killers.”

Absolutely. I was having some fun. But to tell you the truth, mostly at my own expense. But in assigning an occupation to this fellow, it seemed natural to make him a book critic. Because there are some, I think, who make a living by sneering. Most reviewers are honest and try to approach the work in a generous, open-minded way. But some don’t.

Why do you think you’ve stuck primarily with the short story? I mean, you’ve written novels, memoirs, novellas. I remember reading your novella The Barracks Thief—that was your first novel published?

No, I actually had a novel published back in ’75, that I hate so much that I don’t even list it. But then I had a collection of short stories, In the Garden of the North American Martyrs, published in 1981. And The Barracks Thief was in ’84.

And then, as novels go, Old School, which you wrote fairly recently, I imagine?

It came out five and a half years ago.

Was that something you’d been working on for a while?

I had been working on it for a long time. Let’s see—it came out in the fall of 2003, and I’d been working on it since the fall of ’97. So it was a long time coming. And, well, I wrote some short stories in that period, too.

So why do you think you’ve stuck with the short story? (laughs) It’s kind of a dumb question, I know.

No, it’s not. I mean, it’s a question I would ask. But I don’t know the answer to it. I’m working on a novel now, but I don’t imagine it as a vast arc of narrative. I’m thinking of it as having a limited time-frame and a limited cast and limited circumstances, with a single point of view. And so, as I imagine a novel, in structure and concept it probably resembles—structurally, the containment of time, dramatis personae—a story. Take Robert Stone, for example, a novelist whose work I love, take his novel A Flag For Sunrise or Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke: these are vast undertakings, and they have many characters, many points of view. They cover a great reach of time. But my imagination doesn’t work in that way. It’s more tightly focused. And for that reason it leaves out a lot that I love to read in others. But we each after a while have to become reconciled to what it is that our talents and appetites lead us to. For some reason I’ve always been attracted to the incisiveness, velocity, exactitude, precision of a short story, rather than the long journey of those kinds of novels that we’ve inherited from the 18th and 19th century, with all that great robustness and confidence. Some of my favorite novels are really short. I don’t think they’re better because they’re short, but I do have a particular fondness for novels like All Quiet on the Western Front, or William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow. There’s Marguerite Duras’ wonderful short novel The Lover. Or Jeannette Haien’s book The All of It. And Phillip Roth’s The Ghost Writer—a masterpiece. An absolute masterpiece, I think. I don’t think it’s a better novel than American Pastoral—in fact, American Pastoral is probably one of the three or four best novels I’ve read in the last ten years. But The Ghost Writer is right up there for me. And of course Roth was an extraordinary writer of short stories—Goodbye, Columbus…

No, it’s not. I mean, it’s a question I would ask. But I don’t know the answer to it. I’m working on a novel now, but I don’t imagine it as a vast arc of narrative. I’m thinking of it as having a limited time-frame and a limited cast and limited circumstances, with a single point of view. And so, as I imagine a novel, in structure and concept it probably resembles—structurally, the containment of time, dramatis personae—a story. Take Robert Stone, for example, a novelist whose work I love, take his novel A Flag For Sunrise or Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke: these are vast undertakings, and they have many characters, many points of view. They cover a great reach of time. But my imagination doesn’t work in that way. It’s more tightly focused. And for that reason it leaves out a lot that I love to read in others. But we each after a while have to become reconciled to what it is that our talents and appetites lead us to. For some reason I’ve always been attracted to the incisiveness, velocity, exactitude, precision of a short story, rather than the long journey of those kinds of novels that we’ve inherited from the 18th and 19th century, with all that great robustness and confidence. Some of my favorite novels are really short. I don’t think they’re better because they’re short, but I do have a particular fondness for novels like All Quiet on the Western Front, or William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow. There’s Marguerite Duras’ wonderful short novel The Lover. Or Jeannette Haien’s book The All of It. And Phillip Roth’s The Ghost Writer—a masterpiece. An absolute masterpiece, I think. I don’t think it’s a better novel than American Pastoral—in fact, American Pastoral is probably one of the three or four best novels I’ve read in the last ten years. But The Ghost Writer is right up there for me. And of course Roth was an extraordinary writer of short stories—Goodbye, Columbus…

That’s an exquisite collection.

It is. It’s a great collection. Obviously his imagination has led him in different directions over the years. I bet he’d be hard-pressed to say why. I think forms have a way of choosing us, and that, as we start writing, something about our natural appetites—maybe it has something to do with the size of the subject—will lead us toward one particular form or another.

And that’s why I felt hesitant to even ask why you write short stories. Because you write short stories, ultimately, simply because you write short stories.

Yes, but I think it’s fair to try to give some account of why a writer works more in one form than another. And some interesting answer should be possible. In the end—well, there’s a line in one of Gerald Manley Hopkins’ poems that says, “What I do is me: for that I came.” And there’s something mysterious about that, isn’t there?

I think of writers like Chekhov or Babel or Munro, who stick primarily with the short story…

Carver.

Absolutely. And I think they just write what they write, like you said, because the form chose them.

In some odd way it does. God knows we’re not doing it for money. There was a time when you could do very well as a short story writer. People made amazing amounts of money for short stories back in the ‘20s and even into the ‘30s and 40s…

Fitzgerald made quite a living, right?

Oh, it’s amazing how much money he got. Unless I have this wrong, I think he would get $25,000 for a short story. So there was a time when people did very well by short stories. But there can’t be any reason now to do it but the love of the form. If you’re very lucky, you’ll place your story where a lot of people will read it. But you have to be lucky. Because the venues for short fiction are so diminished, even since I started writing. Esquire just does these little short things now, and the New Yorker used to publish two stories in an issue and now they do one. The Atlantic used to have a short story in every issue and now they don’t have them anymore, they just have the fiction issue in the summer. Cosmopolitan used to publish serious fiction, Redbook and Mademoiselle. Vanity Fair. Those magazines don’t seem to do it anymore. We who write short stories pretty much depend on literary journals now to publish our work, and they don’t have much money. And so we do it because we have to, because something compels us.

Your work has been very influential. Who were your early influences as a writer? Have some of those early influences stayed with you? The touchstones, writers you can still go back to now and read.

Your work has been very influential. Who were your early influences as a writer? Have some of those early influences stayed with you? The touchstones, writers you can still go back to now and read.

Influence changes its character over time. To begin with, there are those books you encounter when you’re young that make you a reader. None of us become writers without first becoming readers. For me it was the Hardy Boys, that sort of thing. Jack London. And, most of all, a now obscure writer named Albert Payson Terhune, who wrote books only about collie dogs.

And you wrote a story, which is in your new collection, about a dog.

Yes. I guess I finally had to. But there are maybe three phases of influence. The one I mentioned already. And then there’s the influence of meeting a style that becomes a way of looking at things, and that you emulate. With a lot of my contemporaries it was Kerouac. E.E. Cummings was very influential. For me it was Hemingway. Not such a bad thing. You have to start somewhere, as an imitator—it’s how we learn everything. And he’s not a bad guy to imitate because, first of all, you find out in short order that you can’t really do what he does. The plainness is totally deceptive, and is the result of lapidary work, and a way of looking at things that is completely beyond you when you begin. But it teaches you something, trying to do it. And then as I grew older it was Katherine Anne Porter and Katherine Mansfield. Chekhov. And, of course, Mansfield learned a lot from Chekhov. I love Porter’s work, still. There is a purity, an emotional texture to her work that nevertheless is not sentimental, and that does not exclude feeling. Sometimes, in some writers, you would almost think it wasn’t respectable to feel—there is such a level of detachment and coolness in the gaze of the writer that the effect can be a little chilly. I admired Chekhov’s objectivity, which was nevertheless infused with emotion. So that’s influential, in terms of when we begin to emulate. And then, finally, as you come into your own, whatever that is, and begin to discover your own gifts—you start to hear the sound of your own voice a little better—you are swayed by a kind of influence that sets the standard by which you want your own work to be read. So when I would read a great story of Ray Carver’s, like “Errand” or “Cathedral,” my thought would be, “I want to write this well.” Not write like him, because I knew I couldn’t. That was his world, his voice, all that. But I want to write a story this good. I want to write a story that affects others the way this story just affected me. That is an enduring kind of influence. And that is a generous kind of influence, because it extends in every direction. I have it when I read poetry, I have it when I see a good play, when I hear music. I want to be able to make someone else feel what I just felt. That’s the kind of influence, finally, that stays with you. Because I’m not going to be Faulkner—I can read Faulkner now, and I’m totally immune to imitation. I love him, but I’m totally immune to any stylistic influence from him. I wouldn’t dream of it. I can read Cormac McCarthy, who’s obviously learned a lot from Faulkner. And as much as I love his work, I wouldn’t dream of trying to write like him. But I think, “That’s just great. I really want to do something this good.” And so he’s influential to me in that way. After a while you are who you are. You don’t try. It just happens to you.