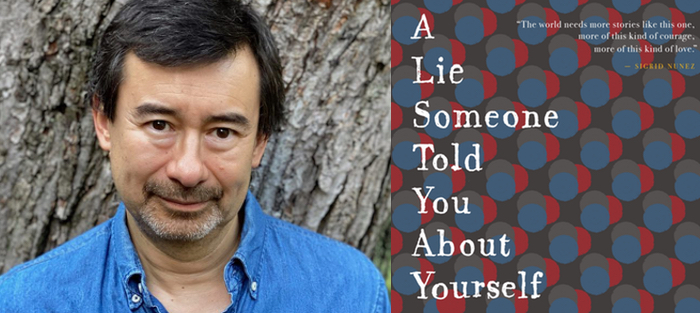

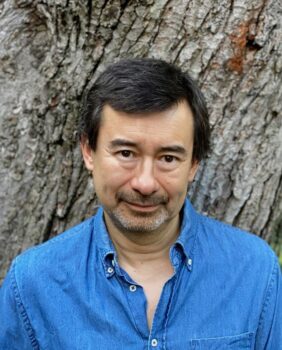

In his latest novel, A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), Peter Ho Davies explores the fraught terrain of pregnancy and parenthood, love and marriage, all through the eyes of an unnamed father. Writing recently in the New York Times, Elizabeth Egan declared: “Other fictional fathers have walked readers through baptism by swaddling/car seat/diaper pail, but this one grabs us around the neck instead of by the hand. We are in it with him, up to our eyeballs in wonder and coziness, uncertainty and frustration, spousal quibbling and second-guessing.” It’s an unflinchingly honest, occasionally uncomfortable but also exhilarating account of the painful decisions parents everywhere must make, and how those decisions echo down through the years.

In addition to this new novel, Davies is also the author of The Fortunes, a New York Times Notable Book and winner of the Anisfield-Wolf Award, and The Welsh Girl, which was long-listed for the Booker Prize. He has also published two short story collections, The Ugliest House in the World and Equal Love. His work has appeared in Harpers, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, The Guardian, The Washington Post, and TLS among others, and has been anthologized in The PEN / O. Henry Prize Stories and Best American Short Stories. He is a recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts, a winner of the PEN/Malamud and PEN/Macmillan Awards, and has taught at the University of Oregon, Northwestern, and Emory University. He is currently a professor of creative writing at the University of Michigan.

Interview:

Travis Holland: The epigraph that opens your novel is a quote from Italo Calvino: “In abortion the person who is massacred, physically and morally, is the woman. For any man with a conscience every abortion is a moral ordeal that leaves a mark, but… every male should bite his tongue three times before speaking about such things.” Can you talk a little about this? Were you hesitant to tackle this subject from the perspective of a male?

Peter Ho Davies: Oh, yes, absolutely. I think that manifests in a number of ways. I think the novel has a kind of metafictional discourse about some of these questions about appropriation, and I think, in this book more than the others I’ve written, I find myself writing into those problems and those challenges. “Can you write this book?” becomes sort of the subject of the book. And I want to be frank about that in this book. It’s a challenge that I was acknowledging. Not that this is the only test to pass in this regard. So I’m not sure that I answer those issues of appropriation so much as acknowledge them in certain ways.

The Calvino quote is there partially as an acknowledgment of those questions. The context of it is a letter he was writing to another male writer, a former friend who had spoken out against abortion. So Calvino was in a sense reprimanding that friend, I think. And I think it speaks to the possibility that there must be some space for men to be allies of a woman’s right to choose, and how do we speak into that space. So I think Calvino speaks to my own anxieties, but also represents an example of a man speaking up in support of woman’s right to abortion. There’s actually a very small callback to that epigraph towards the end of the novel where the character talks about biting his tongue when he’s roughhousing with his kid. So it’s something of an echo of that epigraph.

You know, the book began as a story that I wrote twelve or more years ago and published perhaps ten years ago. And I thought that was going to be it. There’s something more modest about writing a short story—the novel demands more space for itself in the world, in a way. I thought when I’d written the story, I’d said what I had to say, regarding the experience. And it was in some way in giving readings of that story at various places—I think I remember reading it at the Bear River Writers’ Conference—it always felt as though it was a powerful story to read. Powerful for me, but also one readers really responded to. One of the encouraging elements was that, nearly always when I read it, there would be a few people in the audience, often women, who would come up to me afterwards. You could tell that they shared something of an experience along these lines. And I felt a great gratitude to them for that, for telling me that I wasn’t alone in this space as well. And it made me think that there was probably a space for a novel that began to address some of these anxieties and questions. That there may be a way to get beyond that reticence of being a man trying to write into this experience.

You know, the book began as a story that I wrote twelve or more years ago and published perhaps ten years ago. And I thought that was going to be it. There’s something more modest about writing a short story—the novel demands more space for itself in the world, in a way. I thought when I’d written the story, I’d said what I had to say, regarding the experience. And it was in some way in giving readings of that story at various places—I think I remember reading it at the Bear River Writers’ Conference—it always felt as though it was a powerful story to read. Powerful for me, but also one readers really responded to. One of the encouraging elements was that, nearly always when I read it, there would be a few people in the audience, often women, who would come up to me afterwards. You could tell that they shared something of an experience along these lines. And I felt a great gratitude to them for that, for telling me that I wasn’t alone in this space as well. And it made me think that there was probably a space for a novel that began to address some of these anxieties and questions. That there may be a way to get beyond that reticence of being a man trying to write into this experience.

Reticence is the word. Reading your book—well, it’s extraordinary that in 2021, it still felt like fresh air and light was being let into this particular subject—I remember thinking, “Finally someone is talking about this in an unflinching way.” It felt like a subject that has been avoided in some ways, as if there was a shame around abortion, so much shame that even fiction—fiction which touches on everything in the human experience, and absolutely should touch on everything in the human experience—wouldn’t touch this particular subject. A shame that even literature wasn’t self-aware of, as if we were avoiding the subject without even being quite aware of our avoiding it.

I think you’re right. I’ve been thinking a lot over the last few years, particularly after my experience reading the story before audiences, about what it means to say something that feels unsayable. And I think I tried to work that into the book. It’s difficult in a way to give interviews about the book, because most of the things I want to say I said in the book. But there’s a sense in which trying to address this thing that is taboo, I suppose in some ways, that is shot through with questions of shame, feels very arresting for readers and listeners. But it’s also empowering—not only for me as the writer, but perhaps for some of the listeners and readers as well. It’s an act of communication of something that I wasn’t sure I was allowed to say to somebody who wasn’t sure they were allowed to feel what they were feeling. So it feels like we’re communicating something that we weren’t even intending to communicate, something that normally lies beneath the level of communication. Which speaks to that electricity I felt when I first started reading the story aloud to audiences.

And speaking of biting one’s tongue three times, and maybe taking that deep breath before stepping through a particular door: this feels like an intensely personal novel. Autofictional, in a way. We have a writer who teaches at a university, who once studied physics, as you did. A writer who frankly resembles you in many ways. And the book acknowledges the fact that readers are going to conflate the husband in the novel with the author. You write: “If he ever did write the story… there was a chance that it would be true, a chance that it would not. A story, at least, could be both.” So how comfortable or uncomfortable were you with that aspect of the writing—the pouring of oneself into the work, the true and the not true?

I was—and remain, I should say—somewhat uncomfortable with it. So it’s a book that feels like it’s on the edge of something inappropriate, I think. And again, that speaks to this notion of saying the unsayable, I suppose. The process of writing it was to some degree a process of reconciling myself with some of those steps and those risks, and approaching them serially at different points in parts of the book. That is, I felt like I had to touch on them again and again in the novel. When I first wrote that story—even before I published it—I was trying to make my mind up about whether I liked it. And what came to me gradually was that feeling of, “Is this fiction? Is it nonfiction? Where does the truth or the autobiographical give over to the fictional?” The uncertainty of that on the part of the reader feels like an analogue of the uncertainty the characters in the novel are feeling in regards to the medical diagnoses—that sort of shimmering uncertain space. And I realized that I didn’t have to declare it to be this or that, memoir or fiction. It could operate in that liminal space. And that ultimately felt like a formal choice, as it related to the material. And I felt an obligation to remind readers of this uncertainty throughout the novel. Because in a way putting the reader into the uncomfortable spot of not knowing just what is true and what isn’t is a way of putting them into the uncomfortable spot the characters are in.

And of course naturally I felt some anxiety writing about people I’m close to. My son, for instance—or anyway, a son, in the case of the novel. So I intentionally kept that figure unnamed. None of the characters are unnamed, in order to give the writing a bit of wiggle room, in a sense. There’s a scene in the novel when the husband and wife are celebrating the finishing of the book with a toast, and the wife says, “Everybody’s going to think I’m an alcoholic,” and I point out in the text that that too was a fictional moment, just in case readers made the assumption that this was a real person and not a character in a novel. So yes, it’s a constant negotiation. Because I wanted to maintain the openness and vulnerability of fiction.

And I also think there’s a thematic element here—in the ways we all imagine the lives to come, the lives of those cells in the womb, how easily we imagine those as human beings, as children. The certainly of imagining that future is a kind of fiction in its own right.

Were there ever moments when the writing of this novel just scared the hell out of you? When you thought, “No, I can’t write this closely to my own life?” Even as you kept this notion of autobiographical uncertainty, even as you worked to remind the reader that this is fiction. Because of course some readers are going to simply assume that all of this is true.

Oh, there were many of those moments. I can remember showing the novel to my wife, and trying to get a read on how right or wrong this might be. And I’m lucky she’s a writer, so she gets many of these questions, and I think she was very supportive in this regard. But there was a part of me that would have been slightly relieved if she’d told me there was no way I could write about this. So that was certainly a factor.

If you were giving advice to a writer, to one of your students who was hesitant to write about something difficult in their lives or perhaps just a difficult subject, what would you say?

It’s a very urgent question, I think. Because, you know, I feel for young writers. I think it’s a harder writing environment to come up in, in some ways. It’s at the same time a better social environment that we live in now. But I do notice that my students are much more conscious of words and language and choices. And, as I say, there’s real value in that for all of us. But I think that when you’re a writer writing a first draft it’s important to remember that first drafts rarely get things right. You always make mistakes. That’s why we have workshops, it’s why we talk about writing. Particularly when you’re taking on highly difficult, charged material, you don’t necessarily do those things well in early drafts. But that doesn’t mean we should’t try to do them, because once we have that first draft down, we can shape it. I think some of that hesitancy comes from writers thinking that they won’t get it right in the first draft. And one of the things I try to say to writers is that we never get it right in the first draft, but that’s no reason not to try. First drafts are a vital stepping stone on the path to getting a book right. Writing work that is challenging to us personally, but which is also meaningful to us personally, is the way to become a better writer. You set the bar of the writing at one place, when your confidence and competency as a writer may be lower than that place—when you do that and the material is truly important to you, you often rise to the level of the challenge. There’s a bootstrapping effect. The way to make quantum leaps in our work is to take on material that you think you can’t or shouldn’t or are not ready to write yet. The material demands that we become better writers. There’s something to be gained there, even though we’re often of course anxious and fearful of taking on that material. The gains are nonetheless significant for us as writers and for the power of our work as well.

It’s a very urgent question, I think. Because, you know, I feel for young writers. I think it’s a harder writing environment to come up in, in some ways. It’s at the same time a better social environment that we live in now. But I do notice that my students are much more conscious of words and language and choices. And, as I say, there’s real value in that for all of us. But I think that when you’re a writer writing a first draft it’s important to remember that first drafts rarely get things right. You always make mistakes. That’s why we have workshops, it’s why we talk about writing. Particularly when you’re taking on highly difficult, charged material, you don’t necessarily do those things well in early drafts. But that doesn’t mean we should’t try to do them, because once we have that first draft down, we can shape it. I think some of that hesitancy comes from writers thinking that they won’t get it right in the first draft. And one of the things I try to say to writers is that we never get it right in the first draft, but that’s no reason not to try. First drafts are a vital stepping stone on the path to getting a book right. Writing work that is challenging to us personally, but which is also meaningful to us personally, is the way to become a better writer. You set the bar of the writing at one place, when your confidence and competency as a writer may be lower than that place—when you do that and the material is truly important to you, you often rise to the level of the challenge. There’s a bootstrapping effect. The way to make quantum leaps in our work is to take on material that you think you can’t or shouldn’t or are not ready to write yet. The material demands that we become better writers. There’s something to be gained there, even though we’re often of course anxious and fearful of taking on that material. The gains are nonetheless significant for us as writers and for the power of our work as well.

I wonder too if that fear, that sense of trepidation and anxiety, is maybe our way of knowing that we are reaching for that higher level that you talk about. If you didn’t feel that, if you don’t feel any doubt or hesitancy—I mean, has anything truly difficult, anything worth doing, ever not come with those feelings?

Right. And that’s how you know when you’re saying the unsayable. If you want to tap into that power source, that anxiety is the sign that you’re getting to that place. So in those ways, maybe we should embrace the fear and anxiety. Because ultimately those feelings tell us we’re saying things that are worth saying.