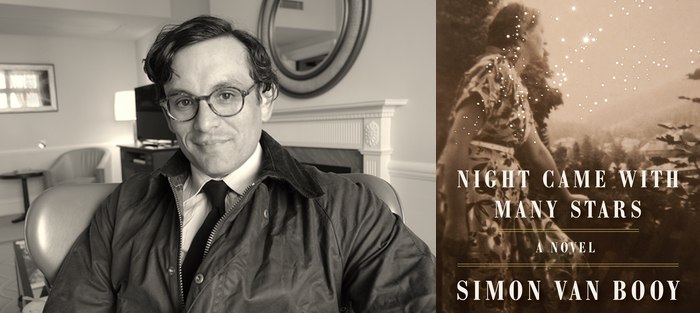

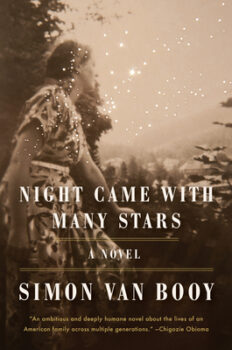

In 1930s rural Kentucky, Carol, an illiterate thirteen-year-old girl with a gift for baking biscuits, is given to her father’s drinking buddy when he loses a poker game. In 1990s suburban Louisville, Samuel, a middle-school boy, is accidentally blinded in one eye by his troublemaker best friend in shop class, and struggles with where he belongs, and how he should be in the world. Their stories of chance and resilience weave together over the course of Simon Van Booy’s new novel, Night Came with Many Stars (Godine), which is set in a gorgeously conjured Kentucky landscape. This is an ensemble narrative, with stories and perspectives spanning the 20th century. What connects them is place, and the search for a sense of home and safety—whether that means a car, a house, a piece of land, or another person. They are also connected through the strength and ingenuity of girls and women, whose stories in this novel are searing and unforgettable.

Simon Van Booy was raised in rural Wales and the countryside around Oxfordshire, and attended college in Kentucky on a football scholarship, where he lived for several years afterward. Night Came with Many Stars is his fourth novel, though he has written more than a dozen books across multiple genres. In the acknowledgments of this new book, he writes that the inspiration for many of the stories in the novel were gleaned “on porches, long drives, in fields, in locker rooms, and around dinner tables” during his time living in Kentucky.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: As you progressed in writing Night Came with Many Stars, how did you develop the narrative structure?

Simon Van Booy: I wanted to give the reader the experience of growing up in Kentucky fifty years apart, but also as a girl and as a boy. I had to sacrifice pacing to do this, but as this is not commercial fiction, I felt I could do it. The structure gave me no end of headaches. One technique I used to try to get it “right” was to keep printing it out and approaching the text as a “reader.” Gaining an objective perspective, though, is one of the challenges of our craft, I think.

Writing across difference is such an important part of the American literary conversation right now, and in Night Came with Many Stars, you have done so convincingly, movingly, with characters that differ from you in nationality and/or gender, race, class, and disability. Why did you decide to write this story now?

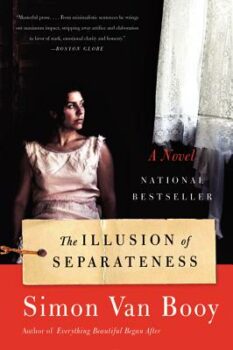

It really comes down to a question of craft, or my lack thereof. For decades I didn’t have a clue how I would bring all the stories together as the single narrative of a novel, because there’s often no tangible plot structure to memories. I had experimented with the idea of no main character in The Illusion of Separateness (a technique I learned from the painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder), and when my dear friend Joshua Bodwell (now also my editor) sent me Kent Haruf’s trilogy, I immediately began to see structural possibilities that might work for this novel.

It really comes down to a question of craft, or my lack thereof. For decades I didn’t have a clue how I would bring all the stories together as the single narrative of a novel, because there’s often no tangible plot structure to memories. I had experimented with the idea of no main character in The Illusion of Separateness (a technique I learned from the painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder), and when my dear friend Joshua Bodwell (now also my editor) sent me Kent Haruf’s trilogy, I immediately began to see structural possibilities that might work for this novel.

“Writing across difference” is, as you say, an important part of the literary conversation, though I choose what to write with the same luck as choosing what to dream at night. Once I get excited for a story, I always write it if I have the technical ability—even if there’s no chance of ever selling it. That’s because once you begin to put conditions on the imagination, it’s all over.

In terms of the diversity of my characters, many, if not all, are based on real people. Like many artists, I suspect, I’ve never really fit in anywhere properly, and so this has resulted in a chronic social drifting. My mother was an immigrant to the UK from the tenement yards of Jamaica, and so growing up I was always viewed as someone “foreign,” and asked where I was from, despite not having even ventured abroad for a holiday until I was fourteen.

I suppose at the time the way I looked didn’t correspond to people’s idea of “Britishness.” I had a long conversation with Peter Ho Davies about this some years ago—he’s Chinese and Welsh, but lives in the Midwest now. Of course, in the United States, I’m seen as British through and through, but it doesn’t really reflect the truth of my childhood. And so when I moved to Kentucky at seventeen to accept an American football scholarship, I felt culturally rootless, like a sponge in search of water, which I think allowed me to be very open to all the cultural experiences I had.

Also, because I had no plans of ever returning to the UK, I was more than open to seeing Kentucky as home. College football teams are socially, economically, and racially diverse, and in the few years I lived there, I really got to see a cross-section of life in Kentucky. Some of what I witnessed was infuriating, but with few exceptions I was shown love and warmth by everyone. And I’ve never been anywhere else in the world like that ever since. And so this book is not really me looking into that world, but rather me looking out from it. Writing the novel was not so much an intellectual exercise as it was an empathetic one.

This is an intergenerational story shaped by the life of one child conceived through the rape of another child, and a woman’s home abortion that nearly kills her. Their stories resonate throughout the entire work. How did these parts of the story emerge?

They emerged from stories I was told directly, and enhanced by research, primarily through a brilliant scholarly work, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867-1973, by Leslie Reagan. This book really opened my eyes. But where there’s pain and injustice, there’s also redemption and forgiveness, I think it’s worth mentioning that.

The threat of sexual assault motivates your female characters to action in a range of ways. When did you realize that this was an important theme in the work, and how did you approach writing it? I noticed the many different ways women react to the threat of sexual assault in this novel, which is, of course, true to life. No one reacts or attempts to defend herself in identical ways.

Over the years, friends, colleagues, and even family members have confided in me or come to ask for help because of a sexual assault—the prevalence of which in the world is higher than I think anyone realizes. I know this is a cliché, but I think men need to do more, hold each other accountable for the way they talk about women and view women. I have tried to do that—even when it meant the threat of violence. What I mean to say is that it’s something I feel very strongly about and not a subject that solely lives within the boundaries of my writing life.

Much of the critique about women’s autonomy and reproductive rights is implicit, and—with the exception of the resourceful and raucous Bessie—voiced by men: Harold, Joe, and Samuel’s father, who also gives Samuel some wonderfully dubious advice about drinking and relationships. How did you decide which characters would imply commentary about women’s oppression?

I just tried to stay true to who the characters were and tell the stories in ways I felt worked, as a writer and a human being. But I think what you say about implicitness is interesting, because so much of what’s damaging to individuals and society, in my opinion, is so embedded in our culture that people don’t even recognize it’s there until they become a victim, or someone they care about becomes a victim. If you look at people in history, so many of the things they did and believed were considered “normal” until someone came along and helped them see that just because something is ubiquitous and customary, it doesn’t mean it can’t also be quietly devastating.

I just tried to stay true to who the characters were and tell the stories in ways I felt worked, as a writer and a human being. But I think what you say about implicitness is interesting, because so much of what’s damaging to individuals and society, in my opinion, is so embedded in our culture that people don’t even recognize it’s there until they become a victim, or someone they care about becomes a victim. If you look at people in history, so many of the things they did and believed were considered “normal” until someone came along and helped them see that just because something is ubiquitous and customary, it doesn’t mean it can’t also be quietly devastating.

Likewise, I noticed that there are not many explicit emotional beats in the novel. Vivid description, action, and dialogue help you portray the characters’ motivations, fears, and desires, but when we’re in characters’ heads, we don’t get the pulse check that’s a feature of many contemporary novels. It reminds me, in some ways, of reading Laura Ingalls Wilder or Albert Camus—wise novelists acutely aware of the social issues that run through their work, but whose writing predates post-structuralism, whose characters predate or have not been touched by the idea of psychoanalysis. At what point did you make this stylistic choice, and why?

Wow, what a question! I wish I had an equally impressive answer, but the truth is rather boring: writing for me is purely instinctual. Though saying that, I do make important choices during the editing process, but they are more to do with enhancing what’s already there. And with every book I feel like I’m starting again. But when it comes the editorial stage, experience is certainly cumulative and that helps things move along at a good rate, in terms of finishing a book. I’m actually quite interested in deconstructionism and French post-structuralism, but when it comes to fiction, it always starts with a deep feeling that wants to find a way into the world. I suppose the story is its journey.

The William Steig children’s story Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, from which the title of your novel comes, is also about trying to get home over time, and similar to your new novel, the resolution is bittersweet (and tied to a picnic blanket.) How and when did Steig’s story become an influence on this work?

I read a lot of books to my daughter, and this one stood out because there’s no greater nightmare than for a parent to lose a child. Usually it’s the other way around in children’s fiction. In this book, there was something about how Sylvester was returned to his parents, which had a deep emotional impact on me. It’s such a good story, blending Buddhist ideas, with Orphic myth, and so many other ancient threads worth following.

You are a prolific writer, whose work spans adult fiction, middle-grade fiction, and philosophy. What is your writing process like across genres? Do you stagger writing these different ways, or do you shift back and forth with two or more works in progress at a time?

I shift back and forth with two or more works in production at any one time. I usually give about two months to each, so that every couple of years I have two or three books. It’s wonderful to spend two months reading poetry and working on literary fiction, but then it’s nice to switch to say, horror, or science fiction, and work on world-building for a couple of months. Working on literary fiction is the most emotionally draining, but also the most fulfilling. I couldn’t do it every day though, as I’d have nothing left to give my family and friends.

Given how much ground you’ve covered in your work, are there places you’d like to go that you haven’t ventured yet? And: what comes next for you?

As you know, writers often work a book ahead, so Night Came with Many Stars was finished in 2018. However, I decided to change publishers and this lengthened the time from desk to independent bookshop. Also, my editor, Joshua Bodwell, gave me edits that really helped me take the book to a level I wouldn’t have been able to do alone. Every writer’s dream, of course, is to have an editor capable of getting the best out of you—even when it hurts to do yet another draft. But the point is that since the most labor intensive work on that book was completed three years ago, I’ve had the time to write a few more stories: a horror novel, The Hive, which I’m writing under a different name; a new children’s novel, Dust Bunnies; and a new work of literary fiction, The Presence of Absence, which I finished in April. All three are with my agent, Susanna Lea, getting the final seal of approval (or not). Hopefully, these will come to market in 2022, 2023, by which time the novel(s) I start now will be finished or near completion.

My advice to any writer is to always start a work the moment one is finished. That way, if you get rejections whilst looking for representation, you at least have another project to keep you occupied. If your work is any good, you will get most likely see a lot of rejection—but that’s for another interview.