Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

Today, we’re publishing a double feature: two essays on Lucia Berlin. Joshua Bodwell examines what we miss when we overlook independent presses like Black Sparrow, which was Berlin’s original publisher. This essay was first published on December 17, 2018, and appears below.

Jennifer Solheim also examines Berlin’s work through what’s often recognized or overloooked—stories like Berlin’s that address issues related to sexual violence, gender, and the female experience. You can read her essay “Safe and Sound: The Indelible Narratives of Lucia Berlin,” which was first published on November 15, 2018.

The short story writer Lucia Berlin has been experiencing a much-deserved surge of interest and appreciation. Berlin’s stories often feature women at the so-called margins, which is to say, women unseen or underappreciated by a society too busy to take much notice of them; Berlin herself worked as a house cleaner, a substitute teacher, and a hospital clerk. Unfortunately, Berlin—who died in 2005—missed the opportunity to feel seen and fully appreciated for her stunning short stories, and to experience the current fanfare around her work. But it’s not that Berlin wasn’t well-published in her lifetime, it’s because we didn’t notice what was right in front of us.

With Farrar, Straus and Giroux’s recent publication of two new Berlin books—Evening in Paradise: More Stories and Welcome Home: A Memoir with Selected Photographs and Letters—on the heels of the surprise success of 2015’s A Manual for Cleaning Women, Berlin’s work is being praised by not only the usual suspects—The Atlantic, New York Times, Paris Review, San Francisco Chronicle, Washington Post—but also in magazines as eclectic as The Economist and Vogue. The coverage is nearly universally euphoric. Evening in Paradise has already appeared on numerous “Best of the Year” lists. But since folks seem to love the story of a “discovery,” commentary on Berlin’s publication history prior to 2015’s A Manual for Cleaning Women is often nonexistent. If a reader were given only The New Republic’s recent Berlin review, loaded as it is with biographical details, they would likely be unaware that Berlin ever published a single story, much less a book, while she was alive. And this is the more troubling trend: Berlin’s publishing history is described in such a way as to fit a narrative that her publications before now were utterly obscure. To say otherwise, it seems, would require the reviewer to admit something none of us like to admit: We missed this.

Specifically lost in the much-deserved celebration of Berlin’s work today is an acknowledgement of the crucial role Black Sparrow Press and its publisher John Martin played in her career. If not for the press’s support of Berlin’s work, her current renaissance might not be happening.

Black Sparrow Press published three full-length collections by Berlin in the 1990s: Homesick: New and Selected Stories (1990), So Long: Stories 1987-92 (1993), and Where I Live Now: Stories 1993-98 (1999). Before these books, Berlin’s stories had only appeared in short, limited-edition chapbooks from supportive but very small presses, such as Turtle Island, Tombouctou Books, and Poltroon Press. These were intimate projects: Bob & Eileen Callahan of Turtle Island in San Francisco had published the poet Edward Dorn, a close friend and mentor to Berlin, and Dorn had likely suggested Berlin to the press, which produced Angels Laundromat; the first edition of Poltroon Press’s Safe & Sound was only 200 copies, which were printed letterpress and typeset in part by Berlin herself.

Berlin had been publishing chapbooks for nine years when Black Sparrow brought out her first book in 1990. In the next nine years, Black Sparrow published three full-length collections in quick succession. The books equal a combined 734 pages. This marked a serious acceleration in Berlin’s trajectory, as the widely available Black Sparrow editions provided readers wide access to her work.

Berlin had been publishing chapbooks for nine years when Black Sparrow brought out her first book in 1990. In the next nine years, Black Sparrow published three full-length collections in quick succession. The books equal a combined 734 pages. This marked a serious acceleration in Berlin’s trajectory, as the widely available Black Sparrow editions provided readers wide access to her work.

Founded in 1966 by John Martin, and perhaps best known for publishing Charles Bukowski, Black Sparrow Press also loyally published authors such as Tom Clark, Wanda Coleman, Robert Kelly, and Diane Wakoski for decades, as well as work by John Ashbery, Robert Creeley, and Denise Levertov. The press was also instrumental in reinvigorating and sustaining the careers of Paul Bowles, John Fante, Wyndham Lewis, Charles Reznikoff, Wright Morris, and James Purdy. Black Sparrow was known for its striking typographical design—by Martin’s wife and collaborator, Barbara Martin—but even more so for its shrewd editorial taste: they published Sam Shepard’s first collection of short stories, and released numerous early books by both Eileen Myles and Joyce Carol Oates long before either became the literary luminaries they are today. But these short lists of Black Sparrow authors only scratch the surface—through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Martin grew the readership of countless writers associated with the San Francisco Renaissance, the Black Mountain School, the New York School poets, and many others.

By the time Black Sparrow published Lucia Berlin in 1990, they were an established, widely known, and revered independent publisher. Yet, in 2015, when the glowing reviews of A Manual for Cleaning Women began to pour in—just as they have again for her two new books—Black Sparrow was either a passing mention, or not mentioned at all. Consider The New York Times: the newspaper published three reviews of A Manual for Cleaning Women, yet only once mentioned Black Sparrow and its place in Berlin’s biography. Reviewer Ruth Franklin wrote, “Though her work was beloved by many writers…she never found a large number of readers—perhaps because she resided on the margins of the literary world…” Similarly, Dwight Garner referred only to Berlin’s first small collection, Angels Laundromat, which he noted in his review “had been published by Turtle Island in 1981.” Only reviewer John Williams accurately noted Berlin’s full publication history, writing, “Through the 1980s, Ms. Berlin’s stories were published by very small presses. In the 1990s, three books of new and selected stories were released by Black Sparrow Press, a midsize independent publisher.”

And that’s just the New York Times.

Most reviewers continue to act as though Berlin was essentially off the radar prior to A Manual for Cleaning Women. Yet can you imagine publishing three books with a well-known independent press in less than a decade and being considered an unknown? In a recent review of Evening in Paradise and Welcome Home for Newsday, Marion Winik humbly asked: “How had we completely missed the eight small-press books this virtuoso short-story writer had published during her lifetime?” It’s a good and valid question, an honest question. And there are others we might ask:

Were the three Berlin books released between 1990 and 1999—books that contained the exact stories in A Manual for Cleaning Women—reviewed by the same newspapers and publications reviewing her work today with such gusto? No.

Were the three Berlin books released between 1990 and 1999—books that contained the exact stories in A Manual for Cleaning Women—reviewed by the same newspapers and publications reviewing her work today with such gusto? No.

Did booksellers take up Berlin work with passion and hand-sell her books? Not likely.

Did we readers, known for our curiosity, seek out the work? No…no, I don’t think we did. After all, when A Manual for Cleaning Women appeared in 2015, there were still first-edition paperbacks of Berlin’s So Long: Stories 1987-92 (1993) and Where I Live Now: Stories 1993-98 (1999) in the Black Sparrow warehouse.

The reality is, in the 1990s, Black Sparrow Press books were neither obscure nor difficult to procure: they were carried by every major distributor, stocked in both national chain and independent bookstores—Homesick, Black Sparrow’s first Berlin book, had even won an American Book Award in 1991. So how, as Winik wrote, had we completely missed Lucia Berlin?

Perhaps, as Jennifer Solheim eloquently argued in these digital pages a few weeks ago in her essay “Safe and Sound: The Indelible Narratives of Lucia Berlin,” the reason has something to do with the cultural moment. Solheim writes:

Storytelling is a place where truth can be spoken, but during Berlin’s lifetime, for the literary establishment to give her greater recognition would have also meant acknowledging the pervasiveness of sexual violence perpetrated against girls and women every day. The literary establishment could have taken Berlin’s work seriously for its aesthetic value, but her work also forces the reader to consider the social implications of these stories of rape and abuse: how they are told, and by extension how they speak. And as we know, the literary world is just as culpable as any other world…

Solheim’s assessment is astute. And there is another major reason so many missed Berlin: the story of not recognizing Lucia Berlin’s talent in her lifetime is in part the story of how independent presses and the role they play in the literary ecosystem are valued, noticed, and paid attention to (or not) by the national media outlets, reviewing engines, and arbiters of culture.

The present celebration of Berlin’s short stories more than a decade after her passing is an opportunity to reflect on what we miss when we don’t explore the work being published by independent presses. We could all stand to look more closely at the ambitious, idiosyncratic publishing lists they are producing. To casually ignore or not actively seek out work from independent presses is to risk missing the Lucia Berlin in our midst today.

There is no question whatsoever that Stephen Emerson, the author who developed and edited A Manual for Cleaning Women, should be commended. The literary agent Katherine Fausset at Curtis Brown, and FSG editor Emily Bell should equally be commended. They all put together, first, a stellar book, and then they threw the house’s substantial marketing and publicity power behind it. Plus, the title is great, the bright salmon-colored cover is striking, Lydia Davis’s introduction adds star power, and the timing was right.

But as we celebrate this belated discovery of Lucia Berlin’s work, it’s also an opportunity to show appreciation for the publisher who supported Berlin’s writing when she was alive: Black Sparrow Press. Had Berlin lived and continued writing, it seems likely John Martin would have loyally continued to publish her. Martin had a reputation for sticking with his authors. He once described his publishing philosophy this way: “Publishers try to develop best-sellers, not authors. I realized I didn’t want to publish books—I wanted to publish authors.”

But as we celebrate this belated discovery of Lucia Berlin’s work, it’s also an opportunity to show appreciation for the publisher who supported Berlin’s writing when she was alive: Black Sparrow Press. Had Berlin lived and continued writing, it seems likely John Martin would have loyally continued to publish her. Martin had a reputation for sticking with his authors. He once described his publishing philosophy this way: “Publishers try to develop best-sellers, not authors. I realized I didn’t want to publish books—I wanted to publish authors.”

Martin confirmed this to me in a recent email. He wrote, “When a publisher stumbles across someone like Lucia you thank God and immediately sign her up.” He recalled it was Black Sparrow Press’s longtime printer Graham Mackintosh who introduced him to Berlin’s fiction; Mackintosh and Berlin were close friends. Martin wrote, “The first story I read by Lucia made me determined to publish all of her available work. She blew me away.”

But unless we prioritize and seek out books and authors published by ambitious independent presses—work too often overlooked by national media outlets and reviewing engines—we are left to wonder: If Black Sparrow Press had published another three Lucia Berlin books in her lifetime, would we have noticed?

Editor’s Note:

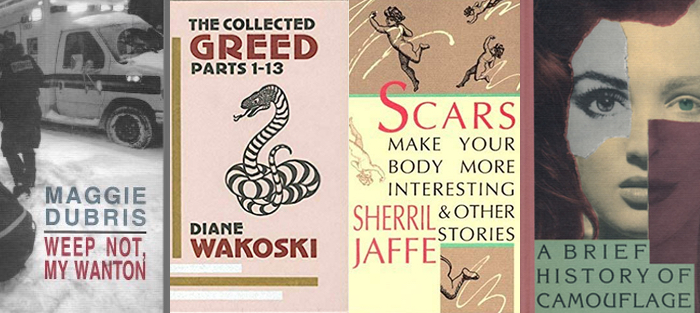

Jennifer Solheim’s essay explored a question asked too little in the midst of the celebrations of the posthumous publications of Lucia Berlin: “What have we lost in the lack of recognition while she was alive?” In the spirit of recognition, here are a few of Joshua Bodwell’s favorites of the many fabulous female authors published by Black Sparrow who are alive and whose work is underappreciated:

- Maggie DubrisThe crackling stories and poems in Dubris’s Weep Not, My Wanton (2002) draw on her experiences as an EMS worker in New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen. This was the last book John Martin personally oversaw before his retirement.

- Thaisa FrankFrank’s approach to the domestic and the ordinary in her longing-filled story collection A Brief History of Camouflage (1992) is poetic and extraordinary.

- Sherril Jaffe Sly and witty, Jaffe’s Scars Make Your Body More Interesting and Other Stories (1975) is so timeless that Black Sparrow revised, expanded, and re-issued the collection in hardcover in 1989 and again in paperback in 1996.

- Diane WakoskiA legend of the long Black Sparrow catalog, Wakowki published her first poetry collection with the press in 1968 and continued to publish with them for the next four decades. Her long, captivating poem “Greed” was released across multiple books, but The Collected Greed, Parts 1-13 (1984) gathers almost all of the epic confessional.