About Alan Cheuse

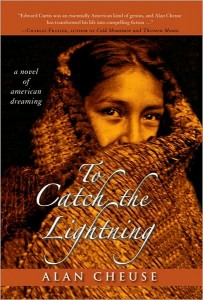

NPR’s “Voice of Books” and a frequent reviewer for All Things Considered, Alan Cheuse is an acclaimed author and critic; he also teaches creative writing at George Mason University. Among Alan’s many publications are a memoir (Fall Out of Heaven), three story collections, and four novels; a book of travel essays, A Trance after Breakfast, is forthcoming this June from Sourcebooks. His most recent book, To Catch the Lightning (Sourcebooks, 2008), novelizes the life of photographer Edward S. Curtis, who devoted himself—at great personal sacrifice—to documenting the rapidly disappearing culture of Native American tribes. To Catch the Lightning was recently awarded the Grub Street Book Prize in Fiction.

This interview was conducted between February and March of 2009. In the first part, Alan responds to questions about To Catch the Lightning and being a novelist; the second section is devoted to Alan’s experience as a book reviewer and teacher—and to his thoughts on the importance and future of the book review.

Part One: On Writing To Catch the Lightning

ANNE STAMESHKIN: What about Edward Curtis’s life and work inspired you to novelize his story, and how long has this idea for a book been with you?

ALAN CHEUSE: It’s so much better to be a reader than a writer. That’s how I always feel when I’ve finished a new novel, and this time around, as I send To Catch the Lightning out onto the waters, it’s no different. It’s been ten years since I began the project in earnest: Months in libraries and museums. Traveling thousands of miles. Reading everything I could get my hands on by Edward Curtis and everything that I could get my hands on about Edward Curtis. And everything about the locations where he worked, and the biographies of the people he knew. And then I wrote draft after draft after draft trying to get the book right.

(My dear late friend John Gardner once opened the front hall closet of his last place of residence, a mouldering old farm house in the Haunted Mountains of north-central New York State and showed me his drafts of Mickelsson’s Ghosts, what would sadly turn out to be his final novel. The stacked pages reached from the floor to the top of the shelf above the coat hooks).

Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis's 'The North American Indian': the Photographic Images, 2001.

I first saw Curtis’s photographs of American Indians in the lobby of an art movie house in Cambridge, Massachusetts when I was eighteen years old and visiting a friend at Harvard. I’ve long forgotten that fellow’s name, but the images on the walls of that impromptu gallery stayed with me. Scene after scene in near-ghostly sepia-near-gold that might have come out of a righteous American’s dream of the last line of the frontier, that line that divided the vision-world of the old days from the quickly ravaged and capitalized land west of the Rockies.

Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis's 'The North American Indian': the Photographic Images, 2001.

Things happen quickly in American history. The transformation of the native Old West to the settled New West took place in the blink of an historian’s eye. Customs that native peoples had practiced since Neolithic times sputtered out like a match in the wind. The cold-hearted ruthless American entrepreneurs, whether after beaver skins or gold in bulk, didn’t care. People like that usually don’t. Though as with the preservation work of a few Spanish priests who accompanied the conquistadors on the destructive trek through the lands of the Mayans in Mexico, there were a few North Americans who felt that disruptive wind blowing and wanted to save what they could of the old ways.

In the case of Edward S. Curtis, Midwestern born Northwestern transplant, the man chose to use his best skills, which had made him into one of the most successful portrait photographers of his time, to create a record of what was quickly blowing away, or sputtering out, on the wind of what most of his contemporaries called progress.

What can a work of fiction about Curtis accomplish that a nonfiction account of his life could not? In other words, why this medium/genre?

Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis's 'The North American Indian': the Photographic Images, 2001.

It’s the quest that caught me. Having written novels about some other Americans who in their heroism and self-disregard had made something out of life in our country that would not have otherwise come to life—journalists John Reed and Louise Bryant, and painter Georgia O’Keeffe—I found myself following Curtis around in the field, the field where he met and lived with and recorded the lives and customs of hundreds of western tribes, and the field of my dreams.

It’s a tricky business, writing about figures out of history. You don’t want to betray any of the known truth about them, but at the same time you know, from living your own life, that so much of the deepest truths about life stay hidden from the eyes of researchers and historians and even friends, even wives and children. It’s that part of the life of the actual figure that you can build fiction upon, based on what you know about what they have written, or painted, or photographed, and what they said on the record about such matters. And in the blank spaces that make up the majority of the space even in the most public of lives–call it life’s dark matter–you can, given what you learn about them, imagine what should have or what, as the first critic, Aristotle said about the difference between history and poetry, what should have happened.

Northwestern University Library, Edward S. Curtis's 'The North American Indian': the Photographic Images, 2001.

So research is not all you need to know, though it helps.

When I told a novelist friend of mine—this would have been in the early 1980s, when after having been fired from a teaching job at Bennington College after nearly a decade of teaching there (not for any cause except that I had come there as a “critic” and had after a short while made the writers and poets, Nicholas Delbanco, Bernard Malamud, Stephen Sandy, Michael Browne, and John Gardner my friends, which among the emotionally impoverished literary theorists in residence smacked of treason) that I had decided to write a novel about John Reed and Louise Bryant, he said, “You’re lucky! All you have to do is do the research and you’ll have it. I have to make things up!” Yes, I said to myself, not knowing anything much about writing novels, I am lucky. But then you do the research and you discover that out of a million facts you had better find the right ones that will give shape and form to your story.

Some tough drafts later I had to admit that I wasn’t any luckier than any other novelist who made things up out of his or her own life and observations about the life everyone else was living. A number of novels and short story collections later, I recall that moment when I understood that I was not so lucky. As I once heard Robert Penn Warren say when he was in his early eighties, every morning I wake up still trying to be a writer.

That’s an important kind of luck. To know how little you know and how hard you have to work to know something. Once when I was eighteen I had that lucky hour when I walked into the lobby of a movie theater. And decades and decades and decades later, I had the luck to try to write about the man who made those photographs. The rest has been the hardest work, but also the most rewarding I’ve ever done.

One recurring theme in the book that struck me deeply was impermanence, the sense that time was running out–not just for the Native American tribes and traditions but for Curtis himself. The choices he had to make between living his own (and his family’s) life and creating a living record of a whole culture were ongoing. How much of this conflict was inspired by research—documents like journals, letters, etc.—and how much was fictionalized? More generally, how much research did you do, and did you do most of it before or during the writing process?

Time never seems to be running out when you’re doing research. You feel as though you can keep on digging forever into the subject. It’s a great way to procrastinate. I learned a lesson doing research for my first novel, the story of John Reed and Louise Bryant (The Bohemians) that only God can know everything, and that after a while you have to stop reading and start writing. That being said, it took me over a decade to complete the work for the Curtis novel.

What books did you read (fiction, nonfiction, research, and/or distractions) while you were writing (or conceiving) the novel? Did you visit any of the places you write about?

I read everything by Curtis, and his cohort, and everything about him, and them, and everything about the period, and the problems of his life and times (and so fiction, nonfiction, newspapers, magazines, journals, research papers)…and I tried to get to all the sites, and failed.

At your McNally Jackson reading in New York last fall you called yourself a “modernist” at heart. What modernist writer(s) do you particularly admire and emulate–or which one(s) do you purposefully distance yourself from?

Every writer in modern times is modern, but not all modern writers employ techniques they admire from Joyce and Woolf and Faulkner and Broch and Proust and Musil and all of that great company. So I see myself as a modern(ist) writer, as are many of our contemporaries. So I don’t see us as living in a so-called “post” modernist period at all. We’re all borrowing these techniques as we need to, but until the great internet novel appears—hah, hah!—we won’t have moved beyond our great masters. We’re all post-Homeric and post-Shakespearean, but still Melvillean and Joycean and Faulknerian and Woolfean, and that’s good enough for me.

What are you working on now, or what is your next project?

I’m working on the page proofs for a collection of travel essays that will publish in June. And completing the textbook—an introduction to college literary study—which Nicholas Delbanco and I have been writing for the past five and a half years. And trying to complete a draft of a novella, and writing reviews.

Part 2: On Being a Reviewer and Teacher

As a well-known reviewer, how do you balance this role with also being a novelist whose fiction is reviewed?

I write about (or review) what interests me, what, mostly, I’d be reading anyway. So it helps us keep in touch with contemporaries, and it’s mostly pleasurable. I don’t know about the balance part, since, as I say, I’d be reading anyway.

I guess part of the “balance” I mean is…what happens when you find major faults in a work you’re supposed to review? What are your thoughts on writing highly critical reviews? In other words, when would you write or publish one and when would you decide to just avoid a review altogether?

That depends on both book and writer. A great writer stumbles, and you humbly point that out. A new writer falters and you might want to keep quiet about that.

I’m glad to hear you say that; of course critical reviews are important, but I like your choice of language…“humbly” pointing something out instead of using someone’s stumble as an opportunity for savage, bombastic wordplay. FWR’s rule is generally this: if a novel or collection is from a small press or a new/emerging author and we wouldn’t recommend it, we won’t review the book at all. If a contributor does like the book despite its flaws, that’s a different story—if there’s a driving reason this author is worth watching or the book worth recommending, we’ll focus on that. And if a book is impressive, if it gets the blood going…well, that’s why we started this site in the first place: to spread the word about and support fiction like that.

So…with all that in mind, what other advice would you offer to fiction writers who also want to write book reviews? And what kind of unique perspective, if any, can reviewers who are also writers offer to readers?

Do it if you can. Reviewing pays you to read what you should be reading anyway (or at least provides you with free reading material). As writers, you can speak to the technical aspects of the book in addition to the effect of the work. An architect writing about houses…a painter writing about a walk through a gallery…a chef making his or her way through a five-course meal…

Tell me about a review you’ve written that you’re particularly happy with, or that was exciting to write.

I remember being happy to try and write well in The Nation about John Gardner’s wonderful (if not now widely read novel The Sunlight Dialogues when it first came out in the mid-1970s…and about Richard Ford‘s novels…and Aimee Bender’s stories (Willful Creatures) and Amos Oz’s fine novel The Same Sea some years ago…and the, alas, late James Welch’s The Indian Lawyer, and nearly a thousand others, mostly pleasurable, on NPR over the years.

Why are professional book reviews important, and what do you think the future of the book review looks like?

With Updike gone, the best reviewer in America is gone. Don’t know what comes after, especially with the demise of book review sections and, help us! some newspapers themselves. NPR now has some of the best book pages in America. But print has to stay in print, because that’s the nature of what we do. One good new idea of late is for nonprofits, foundations, to publish newspapers, and, presumably, reviews along with them…

Are there any books have you read recently that you would recommend to emerging fiction writers? What book is on your nightstand right now?

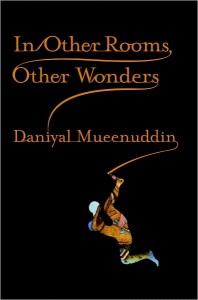

I just read a couple of fine new novels by young writers John Wray (Lowboy, Canaan’s Tongue) and Jesse Ball (The Way Through Doors, Samedi the Deafness), and Infinity in the Palm of Her Hand, an adventurous fantasy about Adam and Eve by Gioconda Belli…and the awful/astonishing The Kindly Ones by Jonathan Littell…though I have to admit I’m sure I’m going to get much more pleasure out of his father’s new novel The Stalin Epigram coming in May. Almost finished reading the fine new short story collection by the American educated Pakistani story writer Daniyal Mueenuddin, In Other Rooms, Other Wonders; it’s the best collection by a new writer I’ve read in years. Greatness always surprises…and he’s something close to that.

How do you balance teaching writing with writing and reviewing? How do these three vocations distract from and/or inform each other?

It all seems of a piece to me, or three sides of the same vocation. Each fires up the other.

If a student approached you for advice about writing a historical novel (or fictionalizing a historic figure, as you did with Curtis), what would you tell him or her?

Seek deep in your heart the courage for this, and make it better than you can even now imagine. Historians do these things superbly, so why do we need a novel? Write a book that answers that question.

Further Resources

– Read an excerpt from To Catch the Lightning.

– View digital reproductions of more than1,500 photogravure images from twenty volumes of Curtis’s The North American Indian–in addition to photographic plates from the portfolios accompanying each volume–on this Library of Congress site.

– Listen to or read some of Alan Cheuse’s book reviews on NPR’s website.

– See a preview of Alan Cheuse and Nicholas Delbanco’s teaching text Literature: Craft and Voice here.