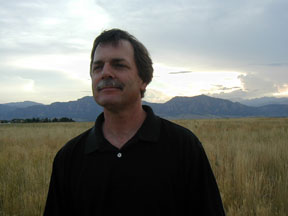

Robert Garner McBrearty is a quiet guy. He doesn’t walk into a room glad-handing and trying to work the crowd, and you’re not likely to find him tracking visitors to his website via Google Analytics. He’s more like a person you find on a back porch at a hectic party and sit down with, only to learn that he’s earned quite a few accolades that louder writers would crow about.

Robert Garner McBrearty is a quiet guy. He doesn’t walk into a room glad-handing and trying to work the crowd, and you’re not likely to find him tracking visitors to his website via Google Analytics. He’s more like a person you find on a back porch at a hectic party and sit down with, only to learn that he’s earned quite a few accolades that louder writers would crow about.

I know this because I experienced it firsthand, working with McBrearty at the University of Colorado-Boulder, where he has taught fiction, creative nonfiction, and composition for the better part of two decades. I don’t know how many times we ran into each other before I knew that he had a short story collection out (A Night at the Y, originally published by John Daniel & Company , or that he had an MFA in creative writing from the storied Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, or that he had won a Pushcart Prize, or that he had received fellowships from the Macdowell Colony and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown.

Like I said, a quiet guy. Fortunately I got to know him a bit, and heard early on about his second collection (Episode, from Pocol Press), and his selection for the 2007 Sherwood Anderson Foundation Award. Since he doesn’t crow about himself, I’ll refrain from crowing too much more about him. Suffice it to say that he has enviable amounts of perseverance as a fiction writer and a new collection out, Let the Birds Drink in Peace, from Conundrum Press in Denver.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: You’re one of those writers who seems particularly dedicated to the short story. Have you tried the “dark side”—novels—and if so, can you delineate your feelings toward both mediums?

Robert Garner McBrearty: I have indeed tried the novel and will continue to do so, though I do feel most at home in the short story form. I think I’m not all that bad at novels—I’ve had three unpublished novels represented by literary agencies, and way back in 1992, I had one novel that passed through several editorial approvals before being turned down by the senior editor at Houghton-Mifflin. That was sort of discouraging. One week I was riding high with anticipation of a nice advance, and the next week I was working in a warehouse. Just a few years ago, I had another close call with another major publisher. I think, though, I’ve never gotten any of my novels completely right. They had some good writing in them—maybe some of my best—and in fact I’ve raided sections over the years and used them in short stories, but I think there’s always been some flaw, perhaps structural, perhaps a need to explore more deeply when I felt like cutting away. The short story provides a fairly clear path, once the idea sets in, so it’s easier to get from start to finish without making too many wrong turns, and if one does make a wrong turn it’s easier to get back on track.

I do have a few other thoughts about it. Raymond Carver was asked once why he wrote the short story and not the novel and he said something along the lines of he wouldn’t mind writing a novel but the short story had fit in more with the rest of his life. I feel like that a bit. I know my own level of hardship was substantially less than Carver’s, but my early years always felt kind of chaotic: bad jobs, moving around, and it was hard to sustain larger works. And then the kids came along and there was a lot of distraction there, so somehow the short story always seemed more doable. Now I’m older and the kids are grown and time seems to be opening up more, so who knows?

I think the short story (I think of Cheever and Hemingway and Carver and Tobias Wolff and Flannery O’Connor and Alice Munro and Donald Barthelme and Barry Hannah and Borges and a host of other great writers) is a wonderful part of our literature. I wish we talked about short stories and short story writers more (obviously, as a short story writer I would be inclined to desire this!). People often talk about what great novel they’ve read—no jealousy here—but too infrequently someone says, “Hey, I just read this wonderful short story in…”

I guess I’m drawn to short stories, too, because I can flip from one idea to another fairly quickly. With novels, a certain level of boredom and confusion and despair always set in. If I screw up a short story, I can move on. Screw up a novel and there goes years of work. Well, not entirely. You learn something from the experience, but it’s rewarding to actually see something in print. If I go through a long period without seeing something of mine in print, the despair sets in. I spend a fair amount of energy warding off despair and the short story gives me more opportunity to ward it off. I couldn’t just write novels and wait years between publication, if they ever got published.

You’re a Western guy through and through—raised in west Texas and a longtime Coloradan—and we did an AWP panel about how writers based in the West deal with the macro-mythos of the West. How is the whole West thing going for you now, especially with the West becoming so homogenous with the rest of the country?

Well, let’s make that south Texas. I grew up in the fifties and sixties as a suburban kid in a large city, San Antonio, so I spent a lot more time riding my bike than riding a horse. In high school, there were “surfers” (who hadn’t quite earned the right to be “hippies”) and “cowboys.” I was a “surfer” by virtue of my longish hair, though I have only been on a surfboard once in my life—a not entirely satisfying experience, though I did have a brief moment of glorious gliding along.

I think, though, that distinction between “surfers” and “cowboys” reflects on the sense of duality I always felt. We were in a new subdivision of modest ranch-style homes, but on the edges of the neighborhood, there was still open land, with cactus and mesquite trees, and outlying houses with sprawling yards where people kept horses. One always knew that rattlesnakes were not far off. I don’t know how frequently it actually happened, but there was always this sense that there were neighborhood fathers cleaving rattlesnakes with hoes.

I think, though, that distinction between “surfers” and “cowboys” reflects on the sense of duality I always felt. We were in a new subdivision of modest ranch-style homes, but on the edges of the neighborhood, there was still open land, with cactus and mesquite trees, and outlying houses with sprawling yards where people kept horses. One always knew that rattlesnakes were not far off. I don’t know how frequently it actually happened, but there was always this sense that there were neighborhood fathers cleaving rattlesnakes with hoes.

One had a sense that the frontier was not far off, both in place and time. My mother’s side of the family, especially, came from ranching roots (small ranches, not the Ponderosa), but I grew up with stories of bandits riding through, battles between the settlers and the Comanche, and of course, the Alamo loomed in my consciousness. So in a way, I was a typical suburban kid riding on a bike, but envisioning riding the prairie. And of course so many T.V. shows and movies of that time built onto the western mythos, and maybe one wanted to claim a little piece of that, the way when the home football team wins, “we” win. So, it’s like, hey, I’m in Texas so there’s a little piece of John Wayne in the Alamo in me. And then later in life one realizes how far one is away from living the myth and one plays off that a bit, so there’s some comic potential there, too.

When I write, I don’t particularly set out to be Western or not-Western. But I consider my roots, how I grew up, and those stories of my upbringing and the mythos of the Western frontier float around in my mind so they are part of who I am, and I allow my subconscious to lead me here or there. Here in Boulder County, I can be walking on a beautiful trail within minutes of leaving my house, and one doesn’t have to be a great adventurer to experience the big sky. Had I grown up in the East, in New York, say, I think I would be a very different writer than I am. I allow the “West” to show up as it shows up. I think it’s similar to the way I approach Catholicism in my writing. I don’t set out to be either a Catholic or non-Catholic writer. The background shows up as in “Hello Be Thy Name.”

In Let the Birds Drink in Peace there’s also a strain of micro-mythologizing: people viewing their lives in heroic terms. We see it in “The Helmeted Man,” “Acting Lessons,” and “The Edge He Carries.” What draws you to them?

In Let the Birds Drink in Peace there’s also a strain of micro-mythologizing: people viewing their lives in heroic terms. We see it in “The Helmeted Man,” “Acting Lessons,” and “The Edge He Carries.” What draws you to them?

Well, at the risk of sounding a bit pathological, I think it may stem from my own sense of self-aggrandizement. But, wait, isn’t that what we fiction writers do? Don’t we write fiction instead of memoir because we want to make the experience somewhat different, maybe larger, than it actually was? So I think as a kid, even, I was always sort of playing “hero” in my mind. Later in life, I acted and I also became a terrific liar. Though most of my lies were really more “bullshit” where I wanted people to figure out somewhere along the way that I was making it up. The reality was kind of boring, so why not tell the tall tale? I like the conflicted hero, the one who has doubts about his own heroism. He keeps replaying it in his mind: was he really brave or just lucky? Didn’t he almost not do the brave action that he did? And what about all the times he didn’t do the brave action at all, but took a pass? As they replay it in their minds, they become less and less sure about their own bravery.

I do look for those moments that stand out in one’s life. I’m talking about the regular person who isn’t exposed to danger on a daily basis, unless of course we view all of life as dangerous, which it actually is if you think too hard about it. But soldiers, say, are exposed to danger in a different sort of way, or activists in despotic countries. The average person goes about his or her daily life and there are only so many times those big moments come, when one can act or not act. I’ve had some times when I didn’t act and those times haunt me, and a few times where I did act—and those times haunt me too. At first there is a desire to pat oneself on the back, but then later the self-doubt sets in.

At any rate, though, I think those moments can make for good fiction. I have an eye toward the dramatic. I like something to happen. In “The Acting Class” the big event actually occurs as a lie/story that the narrator is telling, but I hope the story within a story still has some of that transporting effect that drama has.

Many of your characters are what used to be called “ne’er-do-wells”: people who don’t have much of a shot to succeed, and who frequently berate themselves for not having lived the life they might have. I also see lots of menial labor here: dishwashers, janitors, etc. Why is this one of your territories?

In some ways, my most formative years as a writer were in the years after I got out of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. I graduated from there in 1981, when I was twenty-six. I had an M.F.A. and no desire whatsoever to teach anything to anybody. I spent about five years just working odd jobs. Dishwashing was a big one. I’d done it in college and I was good at it. I had the best hands in the game. I don’t know if it’s still like this, but back then if you had dishwashing skills and an M.F.A, you were in. You were highly sought after… There was one night at a fancy French restaurant where the owner said to me, “You have a Masters degree and you’re washing dishes? You must really be stupid.” I think I was. I was stupid at making money. Other bad jobs ensued. I’m grateful for that time. It’s given me an affinity for people working the menial jobs. I’m very polite to waiters and waitresses or any kind of service personnel. I’m always an inch from getting up at the table and saying, “Hey, I’d better go see if they need help in the kitchen.” I was batting out my stories, working crappy jobs, married by then. I remember my wife (of almost thirty years now) calling home when we were engaged and how thrilled her parents were to hear her future spouse was a dishwasher!

After about five years of that kind of work, though, I was drained. That work experience was sort of mythical, too. I never really fit it, I was never really one of the guys. I was an outsider there, too. I answered an ad for a small school in Berkeley. By then I had a Pushcart Prize (“The Dishwasher,” what else?) and a few other publications and the director there, the poet Philip Brady who went on to become a good friend, liked me and hired me to teach composition, and it beat washing dishes or working in a warehouse.

After about five years of that kind of work, though, I was drained. That work experience was sort of mythical, too. I never really fit it, I was never really one of the guys. I was an outsider there, too. I answered an ad for a small school in Berkeley. By then I had a Pushcart Prize (“The Dishwasher,” what else?) and a few other publications and the director there, the poet Philip Brady who went on to become a good friend, liked me and hired me to teach composition, and it beat washing dishes or working in a warehouse.

For years, though, I would often have some crappy job to accompany my part-time teaching, so I guess there was always a feeling like “success” was something I wasn’t quite experiencing, and I guess that shows up in many of the characters I create…I also have a way, I suppose, where the “boss,” the guy who is more successful, is sort of the bad guy as in “Houston, 1984.” I don’t really mean this as some sort of class warfare statement, but it’s often been my own experience that the guy in charge is something of a prick. So I have a lot more affinity for the underling.

What I hope comes through, though, is that the characters aren’t beaten. Beaten at, certainly, but not beaten.

Colonel William B Travis, commander of the Alamo, appears in “Colonel Travis’ Lament” and in “Alamo Dreams.” He’s not-quite mythic; he’s part of the action, but not central to it. Why are you drawn to him as a character, and is your answer related to your curiosity toward the West, myth-making, and ne’er do wells?

I think that’s one of my more complex stories. First off, it should clearly be read as speculative fiction, even absurdist at times, and is not meant as a reflection on the real-life figures, for whom I have great respect. Still, I could not have written that story without having some obsession with the real life Alamo. I was interested in so many aspects of the story. One was in fact that Travis wrote some very dramatic letters during the siege, calls for help, with the letters increasingly becoming brooding as the calls for help went unanswered. In my story though, one can see that he’s having sort of a great time as he’s writing, really getting into his own mythology about glory and honor and his place in history. So I identified with Travis as a writer, and I thought about what if he was really getting into the writing, that this was the best writing of his life so the writing was kind of really energizing him even though this siege was going on. At the same time, though, the horror draws nearer.

The ne’er-do-wells does fit in here because many of the people of that time came to Texas with past misfortunes weighing on them. Travis’s marriage had fallen apart, Crockett had lost his election in Washington. They were looking for rebirth, new opportunity, redemption. Even in his own time, Crockett was mythologized, his backwoods warrior image blown up way beyond reality.

I show Travis and Crockett as realizing they’ve gotten themselves into a desperate situation, trapped by their own mythology. The situation’s gone too far. What good is being glorified by history if one is about to die? I was also interested in the relationship between leaders and followers, as it applies in many situations, even beyond the military. The little guys, the foot soldiers, get caught up and used by the grandiose ambitions of their leaders. I think of people like Custer here, too, not a whole lot of concern for the men he led to doom. In this case, Travis does care—but it’s too late.

In “Houston 1984” you play with the detective genre in an interesting way—your character actually is a private investigator, so his search isn’t a metaphor for some broader search. It’s the meat and potatoes of your character’s life, which is in no way mythologized at all. What’s going on for you in this story?

Glad you asked. The “1984” plays off Orwell. The story is set before we had as sophisticated spying devices as we have today, but the Boss has a vision of what’s to come when, “we can tap a button and zoom in on any bedroom we want to.” So part of the story is about the loss of our personal privacy and how destructive that can be. As a detective that’s what one does: invade the privacy of someone. In this case, the detective realizes it’s wrong. He’s sympathetic towards the subject of his investigation, and at the end he suspects his actions, his report, has led to a woman’s death. I also wanted to make the detective sort of a regular person—he’s worried about money, he’s got a brother he needs to take care of, and Houston itself is a brooding, violent place, so again there’s that sense of living in a world of siege. One other part, I think, is important. The Boss is also taking about a coming time when the old moral order will be gone, replaced by something else, “…the real scruples. The ones that come when the old scruples have passed away.” But of course the new scruples are pretty suspect themselves. It’s a world, again sort of Orwellian, where bad is good and good is bad, a world where any action can be justified or maybe not even need to be justified because all is okay. In the end, the detective responds with nausea, literally. Nausea at what’s he’s allowed himself to be drawn into, nausea at the situation, nausea at what he’s done.

Glad you asked. The “1984” plays off Orwell. The story is set before we had as sophisticated spying devices as we have today, but the Boss has a vision of what’s to come when, “we can tap a button and zoom in on any bedroom we want to.” So part of the story is about the loss of our personal privacy and how destructive that can be. As a detective that’s what one does: invade the privacy of someone. In this case, the detective realizes it’s wrong. He’s sympathetic towards the subject of his investigation, and at the end he suspects his actions, his report, has led to a woman’s death. I also wanted to make the detective sort of a regular person—he’s worried about money, he’s got a brother he needs to take care of, and Houston itself is a brooding, violent place, so again there’s that sense of living in a world of siege. One other part, I think, is important. The Boss is also taking about a coming time when the old moral order will be gone, replaced by something else, “…the real scruples. The ones that come when the old scruples have passed away.” But of course the new scruples are pretty suspect themselves. It’s a world, again sort of Orwellian, where bad is good and good is bad, a world where any action can be justified or maybe not even need to be justified because all is okay. In the end, the detective responds with nausea, literally. Nausea at what’s he’s allowed himself to be drawn into, nausea at the situation, nausea at what he’s done.

You’ve been a small-press guy throughout your career, and Birds has just been published by the small, relatively new Conundrum Press in Denver. How is this going for you, and how has your attitude toward the press/author relationship changed for you over the years?

Well, to be honest, I would have no objections to a nice fat check from a major publisher.

But first off, let me just say what a great experience it’s been working with Conundrum Press. I met my future publisher, Caleb Seeling, at the Writing the Rockies Conference at Western State College in Gunnison. I handed him copies of my first two books, A Night at the Y, and Episode, and didn’t think too much of it after that. I didn’t make any sort of a pitch or anything: I just said, more or less, hey, hope you enjoy these. Then a couple of weeks later, he called and said he really liked my writing and wanted to do a book. At first we talked about doing a reprint of A Night at the Y, which had gone out of print. But as we talked more, we realized we wanted to do something new as well. So this is sort of a hybrid. It brings back three of my golden oldies from A Night at the Y (hope you don’t mind my calling them “golden oldies,” sort of a little more of my own self-mythologizing), and ten new ones.

But what really comes to mind with this book is personal relationships. I have sat down with Caleb and with senior editor Sonya Unrein and had good conversations about Birds, and also about possible future books. It actually makes me want to write more, as Conundrum is interested in my overall career. It’s a new press, of course, or under new ownership anyway, and I have the first new book out of the blocks, so our fates seem somewhat entwined. I’m certainly rooting for the press, and I know the press is rooting for me.

In terms of small presses, in general, I have to say Hats Off! I never would have survived, emotionally, without them. I was working as a dishwasher when I got the call from Rie Fortenberry from Mississippi Review, speaking some of the most wonderful words I have ever heard: “Robert, this is Rie Fortenberry calling from the Mississippi Review, and I wanted to tell you that your story ‘The Dishwasher’ is going to be reprinted in The Pushcart Prize.” My hearing sort of went out after that, and for a few days I was convinced that someone was playing a joke on me. But being a dishwasher who has a story about being a dishwasher appearing in the Pushcart Prize anthology somehow makes one scrub the dishes with a cheerier attitude. There were other experiences like that, times of gloom, when some acceptance from a literary magazine would come along that kept me going. Those kinds of affirmations were incredibly sustaining. I also appreciate it when an editor takes a second or a third story, as with North American Review , Mississippi Revie w, Missouri Review, and Green Hills Literary Lantern.

In terms of small presses, in general, I have to say Hats Off! I never would have survived, emotionally, without them. I was working as a dishwasher when I got the call from Rie Fortenberry from Mississippi Review, speaking some of the most wonderful words I have ever heard: “Robert, this is Rie Fortenberry calling from the Mississippi Review, and I wanted to tell you that your story ‘The Dishwasher’ is going to be reprinted in The Pushcart Prize.” My hearing sort of went out after that, and for a few days I was convinced that someone was playing a joke on me. But being a dishwasher who has a story about being a dishwasher appearing in the Pushcart Prize anthology somehow makes one scrub the dishes with a cheerier attitude. There were other experiences like that, times of gloom, when some acceptance from a literary magazine would come along that kept me going. Those kinds of affirmations were incredibly sustaining. I also appreciate it when an editor takes a second or a third story, as with North American Review , Mississippi Revie w, Missouri Review, and Green Hills Literary Lantern.

So, of course, not much money in small press publishing, usually not much glory, but mostly I just say “thank God” for the small presses. Brave, noble enterprises! I hope to be sending stories to them for many years to come.