In The Little Bride, Anna Solomon‘s debut novel, 16-year-old Minna Losk travels from Odessa to America as a Jewish mail-order bride. Her motivation is born in from both fantasy and necessity. The journey represents a move toward a more prosperous life, safe from grueling housework and pogroms, a world in stark contrast to the one she has experienced so far—devoid of family, comfort, or a true childhood. She is disappointed to find that her new home isn’t a grand house in a city but a sod hut in the middle of nowhere, South Dakota. And her new husband, Max, is a poor match for the desolate land he has chosen to farm. Old enough to be her father and rigidly Orthodox, Max is kind but perilously stubborn. In addition to grappling with new depths of loneliness, precarious weather conditions, and finger-numbing work, Minna finds herself the stepmother of two teenage sons, one of whom she grows increasingly attracted to over the course of a year.

In The Little Bride, Anna Solomon‘s debut novel, 16-year-old Minna Losk travels from Odessa to America as a Jewish mail-order bride. Her motivation is born in from both fantasy and necessity. The journey represents a move toward a more prosperous life, safe from grueling housework and pogroms, a world in stark contrast to the one she has experienced so far—devoid of family, comfort, or a true childhood. She is disappointed to find that her new home isn’t a grand house in a city but a sod hut in the middle of nowhere, South Dakota. And her new husband, Max, is a poor match for the desolate land he has chosen to farm. Old enough to be her father and rigidly Orthodox, Max is kind but perilously stubborn. In addition to grappling with new depths of loneliness, precarious weather conditions, and finger-numbing work, Minna finds herself the stepmother of two teenage sons, one of whom she grows increasingly attracted to over the course of a year.

Anna Solomon’s short fiction has appeared in One Story, The Georgia Review, Harvard Review, The Missouri Review, and Shenandoah, among others. She is the recipient of two Pushcart Prizes and The Missouri Review Editor’s Prize. Her essays have been published in The New York Times Magazine, Slate’s “Double X,” and Kveller. Before receiving her MFA from the Iowa Writers Workshop, she was a journalist for National Public Radio’s Living on Earth.

In this conversation with Sara Schaff, Anna Solomon considers the nature of short stories versus novels, the process of writing and researching a first novel that is also historical fiction, and the unexpectedly encompassing nature of publicity and self-promotion.

Interview

Sara Schaff: In a recent interview with Erica Dreifus on her blog, you said you once thought that if you could learn to write short stories well, then you could learn to do anything, even write a novel.

Anna Solomon: It’s weird to say this, but I actually feel like a really masterful short story is harder than a good novel because it’s such a demanding form. It feels much more particular, and if things are not perfect, it’s much more obvious. I mean, I think there are perfect novels, but I think it’s less important that a novel is perfect.

There’s more room to breathe in a novel.

Yeah. I think some novels achieve that feeling of unity that you can get with a story, that sense of singularity where you can see it all in one piece. I often think of two different categories of novels—in one category are books like Housekeeping or So Long, See You Tomorrow. I think of books like that as being perfect in what they are, and I feel that part of that is because they’re on the short side and they’re quiet and kind of domestic books. Private books. And then there are books like the The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay and Updike’s Rabbit books that I think of as great novels, but I don’t think of them as perfect novels. And part of what’s great about them is that they’re not perfect; they let so much in, they’re much less precious and fussy in a way. But books like Housekeeping and So Long, See You Tomorrow, I’ve read six times, and I feel like they’re these bibles.

How do you feel about your novel now, compared to your stories? Did writing it feel very different?

It did! You know, I’ve talked to friends who also were writing short stories before they began novels, and they said to me, “I felt like writing each chapter of the novel was like writing a short story, and I was just writing short story after short story.” For me the form felt so obviously different—the pacing, the structure, that part felt very natural to me. I don’t know if it’s partly that my short stories have always been on the long side and kind of begging to be expanded; I also wonder to what degree the subject matter is just so different than anything I’d written. I had never written a historical anything, and I had never thought I would, nor do I really read much historical fiction, but this was the story I wound up wanting to tell.

People who’ve read my stories and read the novel will say to me, oh, it’s totally you; it feels like your writing, which is a great comfort to me when I hear that because in some ways they feel so different.

The fine sentences, the well-drawn characters—that all feels like you. But yes, The Little Bride does feel very different. It’s an epic journey whereas your stories are more contained.

It’s funny because my goal while writing this book felt sort of small. It felt sort of like, okay, all I want to do here is try to write a novel. I just have to see if I can do it, you know? I wasn’t trying to be overly ambitious—when I say that it sounds funny now because I took on a part of history, and I’d never done that before, but in the way I was talking before about the small and large books, it felt to me like a small, quiet book. I know there’s all this epic-ness and sweeping history, but it felt like a book that was very close to its characters, and in that way, kind of contained.

You’re following Minna’s story.

Right, it’s very close to her, and it stays close to her. In the new book that I’ve started writing, the thing I know I want to do this time is open that out. There are many more points of view it’s allowed to go into. It feels much bigger and messier and that’s really exciting, too, but I definitely had to do this first.

I’m starting to research material for a historical novel, and it feels so daunting. What was your process in writing historical fiction—did you research first and develop a sense of the place, or did you start writing the story and then fill in gaps from there?

I definitely did them at the same time. And I think it’s totally daunting, too. Now that I’m facing this other novel, I’m still asking, how are you supposed to do this? And how do you do it as a fiction writer? What’s the obligation to history?

I was fortunate that I came across Rachel Bella Calof, this Russian mail-order bride whose story inspired the book. I was at a residency when I read her amazing memoir, and I was in this place where I was working on a book that was going nowhere, and I was in despair. I started reading Calof’s story, and I got to this line in the first section where she’s undergoing her “Look,” [the physical examination one had to have before being approved as a mail-order bride] and she says, “They inspected me like a horse.” It was one of those lines that said so much while saying so little. And the whole first chapter of the book just kind of came into being. And then I was like, “Oh, I need to learn more.”

I was fortunate that I came across Rachel Bella Calof, this Russian mail-order bride whose story inspired the book. I was at a residency when I read her amazing memoir, and I was in this place where I was working on a book that was going nowhere, and I was in despair. I started reading Calof’s story, and I got to this line in the first section where she’s undergoing her “Look,” [the physical examination one had to have before being approved as a mail-order bride] and she says, “They inspected me like a horse.” It was one of those lines that said so much while saying so little. And the whole first chapter of the book just kind of came into being. And then I was like, “Oh, I need to learn more.”

But even then I was always writing. I didn’t really take much time off to just research. I felt like it was really important for me to just keep moving, and have the research grow out of what the story needed me to know. When I was writing the sections in Odessa and needed certain details, like the names of streets she might have run through, I would put X’s, and later I would go and look up names. There’s this great history of Odessa written by a Brown professor, and I would look through it, look through the maps. It didn’t feel to me like those names were essentials, that they were affecting the story, I guess. I certainly think that they can. Seemingly unimportant details can have a huge impact, obviously. But I tried to use the research as inspiration, as much as information that would hold me to something.

So you don’t get bogged down by trying to make everything accurate before you get the story.

Exactly. Because the characters, the actual story, felt a lot more important to me. I think that’s partly because of how I read. When I do read historical fiction, which is not that often, I tend not to be reading for the “Oh, I want to know what it was like to live during this time.” But a lot of people do read it in that way. So at other points, I would get this anxiety, like, “Oh my gosh, this isn’t accurate enough.” I think the book actually wound up being accurate in most ways, but if people wanted to go through it and pick it apart, either from a farming perspective or an Odessa perspective, they could say this or that isn’t exactly right.

But that could happen with any book. You set a story in contemporary times, in a place you know, and someone will find inaccuracies.

Well, exactly. And that’s one of the interesting things about historical fiction. If you open yourself up, the artifice of writing it all is much more pronounced. Writing contemporary fiction, there could be the illusion that it is “truth” in a way, but there’s no such illusion with historical fiction. Any attempt to recreate the past is going to have plenty of falsehoods. Can we even attempt to understand what someone 120 years ago might have been thinking or feeling? I think we can. Do I claim that it’s accurate? I don’t think I’m as interested in that accuracy as I’m interested in the truth of it, on a human level.

While writing this book, I was ignorant about a lot of things, and I think that was good. There were a lot of things I didn’t think to worry about, and that part of what just let me do it. My sense is that with each book I write, the book will be better, but I will also be more aware of these important questions, and that awareness is going to make the process, not necessarily more difficult, but more fraught. There’s something very freeing about ignorance.

I’ve heard other writers say that the second novel was actually harder. Because of the expectations attached to a second book.

Yes, and now I can understand my process and understand what worked and didn’t work and therefore expect myself to fix all of it, but I might not have all the tools yet.

The novel is both a page-turner and a character-driven story. In literary circles the term “plot-driven” can be pejorative, as if a good plot precludes good writing or good characters. But Minna’s character really drives the forward momentum of The Little Bride. What she does and how she reacts feel very real and organic. How did you write and develop her character and the story?

This question is the hardest for me to answer because I was not that conscious of how it happened. I know what I don’t do. It is organic in that I didn’t go through and make decisions about her character before I started writing her. She came to be who she was through the writing.

On a story level and on a plot level, I did know where the story was going. I really wanted to have a story-driven, plot-driven book when I launched into the longer form of the novel because I didn’t want to be wondering the whole time what it was about. On a thematic level I’m still learning what it’s about, but on a level of what’s happening, I always knew: this is a story about a mail-order bride who goes to America. It was nice to have that basic piece there.

I didn’t know exactly where it would end, and certainly lots of things changed, but I had a sense that this is this journey story, and these are some of the things that are going to happen. It’s certainly not going to be just stuck in her head the whole time. Minna became who she is because of what the story needed her to be. The story also became shaped around who she was. Especially in revision, where I started realizing wait, no, this isn’t really what would happen here. She really wants this, or she needs that. When I went back, she started driving the story more, whereas, in the beginning, she was becoming herself in relation to the story.

I didn’t know exactly where it would end, and certainly lots of things changed, but I had a sense that this is this journey story, and these are some of the things that are going to happen. It’s certainly not going to be just stuck in her head the whole time. Minna became who she is because of what the story needed her to be. The story also became shaped around who she was. Especially in revision, where I started realizing wait, no, this isn’t really what would happen here. She really wants this, or she needs that. When I went back, she started driving the story more, whereas, in the beginning, she was becoming herself in relation to the story.

Minna, though quite young, is so aware of and unapologetic about her desires. She even describes herself as being selfish.

In one sense she’s unapologetic about her desires and openly selfish, and then in another she’s constantly trying to want something else, or to change her desires: “Maybe I could think about it in this way and then I would want what I have. Maybe I could squint my eyes in this way and the room would be different.” But then her actual desire rears up and she’s never able to actually quash it.

Since she was a young girl, she’s had this innate sense of difference toward others—other kids being more religious and other kids being less self-aware. She’s always felt like an outsider, and her self-awareness grows from that. She’s gotten so used to her position as an outsider that she has less need to fit in and please. Some part of her wants to join that world; she looks at the character Ruth and thinks, “If I could just be a good housewife, and I could want that then that would be satisfying and I could just be normal.” But she’s just not. She’s never satisfied with that. She’s also not really satisfied with being unsatisfied, and you could say that’s a particularly modern feeling. But there are certainly lots of characters who were written in much earlier times about very strong, dissatisfied women. Jane Eyre, for instance. Becky Sharp.

Undine Spragg in The Custom of the Country.

You know, I’ve never read that.

People don’t necessarily like the character of Spragg.

Well, people don’t necessarily like Minna either. [laughs]

I was wondering about the “likability” factor. How have readers reacted to Minna?

People either feel that she’s complex and real and they love that she’s not perfect and that she’s not always virtuous or giving. Those people love that she can be all these things. Or they feel, “She is mean and selfish and bad.” I had a friend who leads book clubs, and her book club read it and everyone loved it except one woman who just hated Minna. That’s going to happen.

I certainly want the characters I read to be complex and flawed. It’s important to me, because otherwise I would feel so lacking in my own character if I didn’t get to read other people who were struggling. But some people don’t read for that, and they want a sense of pure escape.

In terms of writing this book, looking back at your short stories, and thinking about the novel you’re writing now, do you see any similarities between your characters? What patterns are you noticing in your own writing?

On a purely external level, [the theme of] coming of age. There are a lot of 16ish-year-old girls – I’m pretty fascinated by that time – I think I always will be. I’m sure that it will change, too, as I get older, but it’s such a ripe moment for characters because there is so much change. That time in my life still feels so vivid, in ways that are not entirely pleasurable. [laughs] The complexity is certainly there.

There are themes that run through a lot of [the work]. One theme would be outsiders versus insiders. Place is also very important in almost all my short stories as well as the book; it becomes its own character. And it’s very important to my writing process.

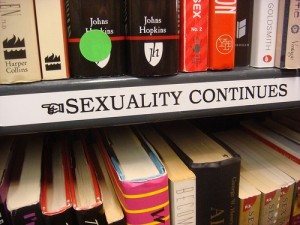

Sex, too. Not just sex, but there’s a lot of complex sex going on. Part of it is power issues around sex.

Sex, too. Not just sex, but there’s a lot of complex sex going on. Part of it is power issues around sex.

And women and young women exploring their sexuality—matter-of-factly, unapologetically. Their exploration often feels like part of their longing for something else.

Yeah, that’s interesting.

In your story “What is Alaska Like?” the narrator’s relationship with Randolph Cunningham boils down to wanting to leave town and her job as a chambermaid. In “The Long Net,” June and her friend encounter a frightening pedophile at a campsite but the story turns on June’s longing for connection with her mom, wanting to be noticed.

It’s funny with “The Long Net” – that was a story where my growing awareness of my themes almost stopped me from writing it altogether. As I was writing I thought, wait, I’m writing “What is Alaska Like?” again. And then I thought, you know what, that’s what writers do. That’s okay. In many ways it felt like a maturing from “What is Alaska Like?” although I still love that story, too.

But those echos can help make a collection work.

Oh, I love that you called it a collection. I hope it will be a collection. It’s cool that you’ve read my stories more recently than I have. It’s such a gift to be read closely and have things be thought about in relationship to each other.

On some level, I write because I want other writers to read what I write and to appreciate it, so it’s been a change getting used to caring about sales. I sold my novel to Riverhead, and it turns out I’ve written a historical novel, and a Jewish novel, and a women’s novel. I’ve done all these things that turn out to be marketable, which of course my agent is thrilled about. The idea that it might actually sell well and catch on in book clubs is awesome. At the same time, I’d like my short stories to be taken seriously, too, despite the fact that stories tend to be tougher on a commercial level.

How do you feel about the self-promotion aspect of being a novelist today?

It was definitely a hard transition this past spring when I decided I had to get myself on Twitter. Well, I didn’t have to, but it’s turned out to be a really good thing. I actually wound up liking it, finding this amazing community of women writers, but also writers of all sorts, and feeling connected through it. I’m not the most natural at social media at all, but I do feel like I’ve been able embrace it.

It was definitely a hard transition this past spring when I decided I had to get myself on Twitter. Well, I didn’t have to, but it’s turned out to be a really good thing. I actually wound up liking it, finding this amazing community of women writers, but also writers of all sorts, and feeling connected through it. I’m not the most natural at social media at all, but I do feel like I’ve been able embrace it.

I’ve also been finding the events totally great. I’m loving readings, I’m loving doing Q & A’s. I’ve been doing a musical and literary performance with my friend, Clare Burson, and that’s been going really well. That part of it I enjoy; it feels really gratifying. Part of me likes to perform, so that’s been great.

The harder fact of self-promotion is how encompassing and full time it is. I remember thinking last year, “When my book comes out, I’m probably going to have to give a good hour or two a week to publicity.” I really thought I would just be able to keep on keeping on with the writing. That [shift] has been hard for me, because I thrive on discipline and routine. It’s the first time in my serious writing life that I’ve taken this kind of break from fiction. I’m writing some essays, which I take seriously, but it’s not the same. And I’m not even doing those in a regular, every-day-sit-down-at-the-same-time fashion. The hardest part of promotion is not the idea of going out there and speaking on behalf of my book, but just the sheer amount of time and distraction. I could see why I would have been a better author fifty years ago, when you just went out, did a few readings, and then went back to your desk.