This fall, Random House will begin distributing titles in the United States by a British publisher named Quercus. Although their debut title, a French thriller called Alex, will certainly strike American readers with the precision and impact of a well-placed bolt of lightning, my affection for all things Quercus took hold long before they translated Pierre Lemaitre’s brutal spectacle of a book into English. Let me start at the beginning. In 2008, my wife and I saw an extremely clever, character-driven vampire film made in Sweden that featured some of the most visually striking cinematography that I’d seen in the theatre in years. It was, of course, Tomas Alfredson’s Lat den ratte komma in, or Let the Right One In. Seeking out the novel of the same title, by John Ajvide Lindqvist (who many readers seemed to consider the Stephen King of Sweden), I was disappointed to find that it wasn’t being marketed in the United States in a cloth edition, which I much prefer. Worse, the available trade paperback seemed to have abandoned any original artistry in favor of cheap film tie-in artwork.

This fall, Random House will begin distributing titles in the United States by a British publisher named Quercus. Although their debut title, a French thriller called Alex, will certainly strike American readers with the precision and impact of a well-placed bolt of lightning, my affection for all things Quercus took hold long before they translated Pierre Lemaitre’s brutal spectacle of a book into English. Let me start at the beginning. In 2008, my wife and I saw an extremely clever, character-driven vampire film made in Sweden that featured some of the most visually striking cinematography that I’d seen in the theatre in years. It was, of course, Tomas Alfredson’s Lat den ratte komma in, or Let the Right One In. Seeking out the novel of the same title, by John Ajvide Lindqvist (who many readers seemed to consider the Stephen King of Sweden), I was disappointed to find that it wasn’t being marketed in the United States in a cloth edition, which I much prefer. Worse, the available trade paperback seemed to have abandoned any original artistry in favor of cheap film tie-in artwork.

This is when I found Quercus, a thriving (and intelligent) publishing house that seemed to have a robust hand in translating quality foreign language literature into the English. Not only did they offer a very nice cloth edition of Let the Right One In that featured original dust jacket artwork that reflected, perfectly, the dusky and haunting nature of the novel, but ordering it couldn’t have been easier. Two more clicks of the mouse, and I was at the webpage for Waterstones (the British equivalent of Barnes & Noble or the now defunct Borders) placing my order. They shipped it right to the door of my house.

Happy as I was with my acquisition, I didn’t really give Quercus much more than an appreciative thought at the time. It would be another year before I really began to more fully recognize the quality of the foreign literature they were purchasing as a house. The first two installments of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and The Girl Who Played With Fire, had come thundering into American bookstores in 2008 and 2009 respectively, and I had a small group of clients who were chomping at the bit for the third. Anyone who’s had been there and done that knows that its heroine, Lisbeth Salander, had been airlifted out of the last pages of the second book with a bullet in her head, and readers wanted to know what was going to happen next. At that point, it was early 2010 and the third book was months away, but some quick investigative work online produced some surprising results: the third book in the Millennium Triology, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, had been available in the UK for almost two years already, and it was Quercus that had first translated all three of them into the English.

Pierre Lemaitre’s shocker, Alex, was released in American bookstores earlier this week, courtesy of Random House (and the Quercus imprint MacLehose, who published it), and although there are some similarities between Lemaitre’s work and Larsson’s, and although Larsson’s readers are certain to devour and appreciate the French author’s Commandant Camille Verhoeven trilogy (Careful Work, Alex, and Sacrifices), Lemaitre should not be mistaken as one riding on the coat-tails of the other, for Alex, grotesque though it may be, is not just another in a long line of shockers seeking to outdo its predecessors, but an extraordinarily innovative work that will stand sturdily enough on its own architecture.

Lemaitre’s book opens ordinarily enough (for a thriller) with its namesake, Alex Prévost, being followed, abducted off of a city street, and savagely beaten by the large, muscular Jean Pierre Trarieux. Regaining consciousness in an abandoned storage facility, she expects to be put to death or raped, but finds, instead, that her captor intends to force her into a small cage, suspend her from the ceiling, and “watch her die.” Of particular note at this point is the idea of watching, for what Trarieux has done to Alex is objectify her by stripping her of everything that makes her something more than an object. She becomes a thing to be looked at. She has lost her free will, her agency, her ability to move, and has become a body in a cage – which is what the novel is really all about.

Lemaitre’s book opens ordinarily enough (for a thriller) with its namesake, Alex Prévost, being followed, abducted off of a city street, and savagely beaten by the large, muscular Jean Pierre Trarieux. Regaining consciousness in an abandoned storage facility, she expects to be put to death or raped, but finds, instead, that her captor intends to force her into a small cage, suspend her from the ceiling, and “watch her die.” Of particular note at this point is the idea of watching, for what Trarieux has done to Alex is objectify her by stripping her of everything that makes her something more than an object. She becomes a thing to be looked at. She has lost her free will, her agency, her ability to move, and has become a body in a cage – which is what the novel is really all about.

The cage she is in is no simple wooden crate but a fillette, a “cage that makes it impossible to stand or sit . . . an instrument of torture created under Louis XI for the bishop of Verdun . . . [that is] very effective . . . [because] the joints fuse, the muscles atrophy . . . and it drives the victim insane.” Lemaitre’s choice of the fillette, aside from its frightening physical implications, is an incisive double entendre that signals that there is more to this book than meets the eye, for the French word fillette can also signify a little girl: the woman is in a cage that is the little girl. Were this the only story thread and these the only characters, Alex would be unbearably serious, but Lemaitre has tempered the book’s intensity with a broader cast.

On the case of the missing Alex Prévost is the trilogy’s namesake, Commandant Camille Verhoeven and his band of merry men. One can hardly imagine calling them anything else, at least while working only from what we learn of them in the trilogy’s second installment, for they effectively provide a degree of levity in what would otherwise be an excruciatingly dark and terrifying narrative. Working with Commandant Verhoeven is the independently wealthy Louis, who arrives at the crime scene in a Brooks Brothers suit, a Louis Vuitton necktie, and Finsbury loafers. No less effective a crime fighter, he is clearly the best dressed character in the book. Providing a comedic balance to Louis is Armand, who, throughout the story, exhibits a frugality that borders on kleptomania. Moving from witness to witness at a crime scene, Armand borrows one or two cigarettes from each person he interviews and, after an hour’s work, has refilled his smoking case. In secondary roles, the reader finds Jean Le Guen, the Divisionaire and Camille’s immediate supervisor, and Doudouche, his cat.

By way of a word of caution, our look at Alex will become a little more ambiguous from this point onward. One of Lemaitre’s best authorial qualities is his ability to subvert his reader’s expectations through a series of shocks and surprises that start pretty close to the beginning of the book and continue for its duration. Unfortunately, it would be nearly impossible to critically approach some of the more interesting theoretical moves that Lemaitre makes without flirting with some of the book’s best surprises. Despite the effort that I’ll be making to be as vague as possible about important events in the book that shouldn’t be shared, readers not wishing to know anything about it ahead of time should stop at this point.

By way of a word of caution, our look at Alex will become a little more ambiguous from this point onward. One of Lemaitre’s best authorial qualities is his ability to subvert his reader’s expectations through a series of shocks and surprises that start pretty close to the beginning of the book and continue for its duration. Unfortunately, it would be nearly impossible to critically approach some of the more interesting theoretical moves that Lemaitre makes without flirting with some of the book’s best surprises. Despite the effort that I’ll be making to be as vague as possible about important events in the book that shouldn’t be shared, readers not wishing to know anything about it ahead of time should stop at this point.

This done, we should return to the fillette, to the prison, to the little girl, to the prison of the little girl, for Alex seems to be less a work about misogyny and violence against women (although it is, undeniably, the axis of the book) as Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy certainly was, and more a work that wants to foil how we read and interpret gender. Lemaitre’s genius is revealed in the careful revelation of his characters, all on a labyrinthine journey to the truth. This is why he has positioned Alex in the role of the victim and has cast Trarieux as the abductor in the book’s opening passages – to later challenge his readers’ assumptions. Trarieux becomes, irrevocably, the novel’s monster and Alex its victim.

This reversal of perceived roles also raises a couple of interesting questions about how we read and about how we frame and reframe our judgment as readers based both on the roles that characters are given to play and on what, here, has revealed itself to be a shrewdly strategized narrative architecture. Are readers more sympathetic to Alex because she is established as a victim and as the book’s protagonist in the first few chapters (or, at the very least, she seems to be the book’s cotagonist with Camille Verhoeven)? Do they stand in judgment over Jean Pierre Trarieux even when the motivation for his actions is fully understood? When the entirety of the tale is told, and the reader reflects upon the story as a whole, do we find that judgment has been reserved until the end, or has the reader made his or her decisions based upon how each of these two characters have been established at the book’s outset?

I like to speculate how these characters would have been read had Alex opened with the brutal serial murder of Pascal Trarieux and concluded with its namesake’s abduction. Would readers see Trarieux as less of a monstrosity and interpret the abduction as justice due, though for what purpose the reader may be left to discover on his or her own. Alex has been positioned at the story’s opening as a victim, and continues, somehow, to occupy that role throughout the novel. From the beginning, she is caged like an animal and objectified, but one of the book’s vicious ironies is that she revenges herself against the character Thomas Vasseur, by also treating herself, in turn, as an object (her body is the cage) and as a piece of physical evidence. Trarieux, likewise never shakes off the yoke of misogynistic violence that is hung over his massive frame at the book’s outset and is not in the least missed when he is gone.

The same, of course, cannot be said of Camille Verhoeven and his raucous investigative team who, somehow, just don’t seem to occupy enough space in the book. Although the first of the trilogy released in the U.S., Alex is the second installment in the series so it’s not at all out of the question that more time has already been spent with these characters in Careful Work. All the same, readers are left hungry for more information both about Verhoeven’s men and the mysterious death of his wife, Irene.

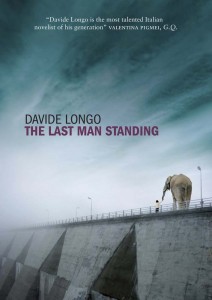

Repulsive though it may be in its darkest moments, Alex is a gripping and extremely intelligent thriller that will fully engage, mercilessly shock, and unexpectedly surprise its readers from its first page to its last, and I, for one, will wait with great anticipation for further translated work by Pierre Lemaitre. It is a worthy American debut from a fine publishing house and I couldn’t be more pleased that Random House will be distributing them domestically. A long-time admirer of well-written, post-apocalyptic fiction (everything from George Stewart’s 1949 classic, Earth Abides, to Peter Heller’s beautifully crafted 2012 fiction, The Dog Stars), I was excited to discover that one of Quercus’ next big titles is a newly translated Italian novel in that vein due in October, The Last Man Standing by Davide Longo, a tale of social collapse. To shamelessly steal a line from one of my favorite films, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Repulsive though it may be in its darkest moments, Alex is a gripping and extremely intelligent thriller that will fully engage, mercilessly shock, and unexpectedly surprise its readers from its first page to its last, and I, for one, will wait with great anticipation for further translated work by Pierre Lemaitre. It is a worthy American debut from a fine publishing house and I couldn’t be more pleased that Random House will be distributing them domestically. A long-time admirer of well-written, post-apocalyptic fiction (everything from George Stewart’s 1949 classic, Earth Abides, to Peter Heller’s beautifully crafted 2012 fiction, The Dog Stars), I was excited to discover that one of Quercus’ next big titles is a newly translated Italian novel in that vein due in October, The Last Man Standing by Davide Longo, a tale of social collapse. To shamelessly steal a line from one of my favorite films, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Further Links and Resources:

- For more information on Lemaitre’s work, please visit the author’s website.

- Read an interview with Lemaitre from Waterstone’s.

- You can also check out an excerpt of the book on Lemaitre’s website.