The LNG Effect

Many first-person coming-of-age novels, particularly contemporary ones, begin with a narrator in want of something or with an action that sets the book—and, thereby, its narrator—into motion. William Maxwell’s So Long, See You Tomorrow begins with a murder; Eugenides’ Cecilia was the first to go; Roth’s myopic Brenda asks Neil to hold her glasses, and from that first snap of the bottom of her bathing suit, we know exactly what is at stake.

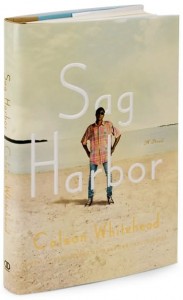

In fact, making sure the stakes are high seems to be one of the first rules of fiction. Yet Sag Harbor (Knopf-Doubleday, 2009), Colson Whitehead’s coming-of-age novel set on Long Island in the summer of 1985, uses a slightly different set of stakes. The book simply begins at the start of one summer and finishes at the season’s end. At first, I wondered, why this summer? The summer of 1985 must have had some earth-shattering event for Benji, its narrator, at least something earth-shattering for a self-aware fifteen-year-old boy: a parents’ divorce, a difficult break-up, the witness of a horrible event. Sag Harbor has no such incidents, but it doesn’t mean the book is without conflict. Benji—who would prefer to be called Ben, and whom I will refer to as such because he is too likable not to honor his wishes—is trying to make sense of who he is, who he’s not, and if it really matters so much to define it at all.

The self-awareness here is not only Ben’s but the season’s itself. Sag Harbor is driven not by plot but by time, by the fleetingness of summer and its constant reminder of that fleetingness. The beginning is slow, with the sense of months ahead, time to digress and ponder and imagine and internalize, with the thickest, most dense prose socked in the middle of July, the more desperate, urgent bursts as we careen toward Labor Day. The writing is wonderfully languorous throughout, like summer itself, and a perfect match for adolescence: unrestrained and indulgent but wonderfully self-conscious as well.

For example, no sooner than the novel announces itself as being about the summer of 1985 do we digress to a roller-rink skating party two years prior, when Ben claims that his psychic release from his younger brother, Reggie, occurred. He and Reggie are less than one year apart and, for most of their lives, behaved and were treated as twins. Yet this early digression feels necessary; that summer it seems Ben and Reggie, though living under the same roof and fraternizing with the same group of friends, have a new distance between them, one that both relieves Ben and makes him wistful.

Such digressions of backstory and exposition are common in Sag Harbor. At first I wondered about the choice to place so much at the beginning of the novel: the risk is that the reader loses track of the present narrative before it even begins. Then again, the longest day of the summer comes not at the end of the season but near its beginning, a fact that always depressed me as a child, that only weeks after school let out did summer reach its peak. So much of this novel is about memory, so much of this novel is about the laziness of summer and its attendant contemplation; so much of Ben’s character and identity is made up of trying to figure out that very character and identity. He watches with anthropological curiosity those of his own age, sometimes his own race: “Keeping my eyes open, gathering data, more and more facts, because if I had enough information I might know how to be.”

Ben’s constant attention to finer points defines him. From a lesser writer, such long digressions and detailed explanations may begin to feel like a literary tic, but here it emerges as Whitehead’s rich, well-appointed style. In a sense, these diversions are the story. The absence of structured narrative is a reflection of summer itself.

In fact, these diversions, distractions, and details are essential to the understanding of the book, and of Ben. The details of others seem to comfort Ben even if they puzzle him. Upon his arrival that summer, he finds his friend NP, of whom he says: “Hanging out with NP was to start catching up on nine months of black slang and other sundry soulful artifacts I’d missed out on in my ‘predominantly white’ private school. Most of the year it was like I’d been blindfolded and thrown down a well, frankly.” While Ben is utterly befuddled by the right way to act—“The guy dropping off the weekly pamphlets outlining the shifting teenage codes and edicts skipped my house, or someone stole them from my doorstep before I got up”—the younger Reggie seems to be right on trend.

In fact, these diversions, distractions, and details are essential to the understanding of the book, and of Ben. The details of others seem to comfort Ben even if they puzzle him. Upon his arrival that summer, he finds his friend NP, of whom he says: “Hanging out with NP was to start catching up on nine months of black slang and other sundry soulful artifacts I’d missed out on in my ‘predominantly white’ private school. Most of the year it was like I’d been blindfolded and thrown down a well, frankly.” While Ben is utterly befuddled by the right way to act—“The guy dropping off the weekly pamphlets outlining the shifting teenage codes and edicts skipped my house, or someone stole them from my doorstep before I got up”—the younger Reggie seems to be right on trend.

It isn’t so much that Ben’s tastes are more “white” and Reggie’s more “black,” though this is definitely the case—Ben, for instance, favors dusty black Converse whereas Reggie begins to wear white Filas, “a little further out into the Street than [they] ever ventured.” While Ben is perplexed by his brother’s footwear choice, more perplexing to him is the way Reggie keeps these shoes immaculate by using a toothbrush dipped into a bottle of ammonia to gently clean them. “Why Filas?” Ben wonders. “Who told him about using ammonia?”

Still, I don’t think it’s any sort of accident that the book is full of black and white imagery: the story is about so much more than race, but Ben is certainly very aware of both the black and white worlds to which he belongs but neither in which he feels completely comfortable.

Still, I don’t think it’s any sort of accident that the book is full of black and white imagery: the story is about so much more than race, but Ben is certainly very aware of both the black and white worlds to which he belongs but neither in which he feels completely comfortable.

During the school year, Ben lives in the city’s white world: a world of prep schools and bar mitzvahs and Brooks Brothers oxfords. In Manhattan, when he and Reggie are dressed in uniform on the way to school, people sometimes assume they are the sons of an African diplomat; on the other hand, Ben feels anxiety about the Famous Black People he’s never heard of. In Long Island’s Sag Harbor, however, nobody finds it odd that he and Reggie attend the school they do nor that they are a black family with a beach house. Ben and his family stay in the Sag Harbor area called Azurest: “the black part of town.” “Sag Harbor,” Ben notes, “was outside the rules.”

Or, perhaps Sag Harbor is a place where Ben can safely figure out just what those rules are. His search is not about how to be black, necessarily, but simply how to be in the know. Perhaps his conflict is one experienced by most thinking, sensitive adolescents: how exactly to be authentic. He describes the handshakes with which he and his friends greet one another as such:

Devised in the underground soul laboratories of Harlem, pounded out in the blacker-than-thou sweatshops of the South Bronx, the new handshakes always had me faltering in embarrassment….No one ever commented on my fumbles, though, and I was grateful. I had all summer to get it right, unless someone went back to the city and returned with some new variation that spread like a virus, and which my strong dork constitution produced countless antibodies against.

Such wonderful, self-deprecating humor is one way the novel, steeped so heavily in nostalgia, avoids sentimentality. But it also does so by at turns moving away from wistful longing and hovering for flashes in darker places: beneath all the boys’ games and mishaps lies a sense of abandonment. Ben and Reggie’s parents, who only make it out to Sag Harbor on the weekends if they make it at all, are hardly in the book, for instance, nor is their older sister, Elena. While in some ways the boys welcome the freedom, there is a sense that the absence of adults affects them in a darker way.

One day, for example, after Ben gets a BB gun pellet lodged near his eye, he and his friends concoct a story about why Ben’s eye is swollen, a story that turns out to be unnecessary:

We rehearsed cover stories and settled on, We were running through the woods to Clive’s house and I ran into a branch that was sticking out! I coulda poked my eye out! That way they could scold us for running in the woods, and leave it at that. But they got home and never noticed. This big thing almost in my eye.

And perhaps such boyish mischief is just that: mischief. Boys will be boys, after all. Yet there is the sense that not all Ben’s Sag Harbor friends turn out okay:

As time went on, we learned to arm ourselves in different ways. Some of us with real guns, some of us with more ephemeral weapons, and idea or improbable plan or some sort of formulation about how best to move through the world. And idea that will let us be. Protect us and keep us safe. But a weapon nonetheless.

We get the sense that Ben in particular wishes he had more attention from his parents, that perhaps he’d wish they’d better protect them. They are not only physically removed from much of the story but inhabit another emotional landscape as well. Though it is subtle, a quiet but palpable tension exists not only between Ben and Reggie and their parents but perhaps between the parents themselves. Once, after their mother returns from a walk, Ben notes, “She made a comment, my father responded in his wisecracking intonation, and both of them laughed. I relaxed. Things seemed okay out there.”

This yearning for when “things seemed okay” in general also permeates the book, and melancholic wistfulness reaches full peak at the end of the summer (and, thereby, the end of the novel) when a certain song on Sag Harbor’s radio station WLNG ignites something in Ben, who has a love/hate relationship with the station, mocking it in public but listening in private. The “LNG effect,” according to Ben, was “a feeling of nostalgia for something that never existed.”

“You can’t say longing without the l, n, and g,” he further points out. And perhaps this book is just that: a nostalgia not necessarily for the Sag Harbor summer of 1985, nor any particular Sag Harbor summer, but instead the potential that each new summer offered, and how each one might feel like it might be the best one yet.

Summer often feels as if we’re waiting for something dramatic to happen: to fall in love, say, or for someone or something new to arrive. But often, the season passes slowly and languidly and uneventfully, and how can we not, as the overworked, overstressed people we are, not find some sort of solace there, in the sense of just waiting, of time passing, the rise and fall of slack water and spring tide?

Summer often feels as if we’re waiting for something dramatic to happen: to fall in love, say, or for someone or something new to arrive. But often, the season passes slowly and languidly and uneventfully, and how can we not, as the overworked, overstressed people we are, not find some sort of solace there, in the sense of just waiting, of time passing, the rise and fall of slack water and spring tide?

Perhaps this is the beauty of adolescence, wanting both to be independent and taken care of; the perpetual waiting for the next thing, the sense that something new or exciting is just around the corner, that we might still wake up, transformed.

And maybe it’s why so many great novels employ this retrospective voice, as Whitehead does so effectively and beautifully here: it’s not really a longing for that time, or even for what was being longed for. Maybe what drives Sag Harbor is a longing for longing, a yearning for a time when the glow of a house as you approached it was enough to make you feel safe, a time when possibilities seemed endless and varied, when something as simple as a haircut or the knowledge of the right handshake, or the realization that these handshakes didn’t matter at all, had the power to change you, to make you into a better version of yourself.

Further Resources

– This page from Colson Whitehead’s website links to various articles and essays he’s written. “Wow, Fiction Works!” (Harper’s, Feb. 2009) and “I Write in Brooklyn. Get Over It.” (NY Times, 3 Mar. 2008) are especially great.

– For a Sag Harbor map annotated by Whitehead, see this Wall Street Journal article.

– The author takes readers on a video tour of Sag Harbor, the place and the book:

– Selected interviews with Whitehead: by Maud Newton (April 29, 2009); by Elliot Holt, for the Rumpus (April 24, 2009); in the New York Review of Books (after Apex Hides the Hurt in 2006); on the Bat Segundo Show (2006): 45 minute podcast; with Powell’s (after John Henry Days, 2001); with Salon (after The Intuitionist, 1999)

– Watch an interview with Whitehead on the Charlie Rose Show (2001)

– Tune in to the nostalgia-inducing WLNG.

– Read more about each of Whitehead’s books on the Biography page of his website.