Kim Church told me she was writing a novel titled Byrd the first time we met. We were at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (VCCA) in Amherst, walking a lane after dinner, cows grazing in the adjacent pasture. I’m sure I heard “Bird” even when it became clear that Byrd is a character. The surprise of homonyms captured me. “This novel,” I thought, “will be poetry.”

Now, four years later, the novel is almost out; I have read the galley and, I’m thrilled to say, I was right.

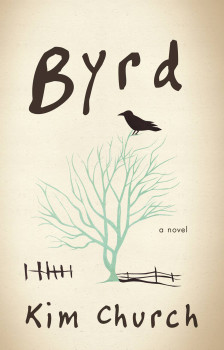

Sparse and complex, Byrd (Dzanc Books, 2014) makes rich use of extended metaphor, offers characters who pirouette in their own spaces and who sometimes collide. The story it tells is both heated and quiet, tracing the life of one woman of her times: Addie Lockwood, who loves books and music and almost loves a boy, and when things get complicated, finds that she must love herself.

The story in brief: Coming of age in the 1970s, small-town high school students Addie, a devoted reader, and Roland, a musician, form an unlikely friendship. Years later, in their thirties, they reunite for a brief, reckless affair that leaves Addie pregnant. Addie, who can be as clear-eyed as she is romantic, chooses to act on her own: she gives birth to a son and surrenders him for adoption without telling Roland—and without imagining how her choices will shape them all.

Adrienne Rich wrote, “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? / The world would split open.”

In Byrd, Addie tells her truth. It is a shocking truth, in many ways taboo. Yet Kim writes it with such compassion, we are compelled to follow.

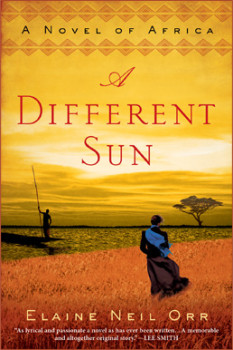

I wore the miner’s hat and brought out a first novel a year before Kim’s Byrd. A Different Sun is quite a different sort of novel: the odyssey of a woman who marries a former Texas Cavalryman-turned-missionary and follows him to West Africa. Yet both novels portray strong female characters who journey into uncharted territories, who are tested to their core, and who grow in unexpected and unconventional ways.

Kim and I started this conversation at Sugarland Bakery in Raleigh, North Carolina. We continued by email.

Interview

Elaine Orr: You know the first question everyone will ask.

Kim Church: I do, and the answer is no.

You haven’t given up a child?

No. My book isn’t a memoir in sheep’s clothing. Addie is a fictional character who has haunted me for longer than I’ve been writing fiction.

Years ago I was having dinner with a friend who casually dropped into our conversation the fact that he’d fathered a child who “had to be” given up for adoption because he and the mother had “waited too long.” He didn’t say how he felt about this—he seemed oddly blank—and I didn’t ask. All I could think was, what about the mother? How did she feel, knowing she had a child in the world, one she’d carried and delivered and chosen to give up? For her, I was sure the story would be more than casual dinner conversation.

I thought about this woman a lot over the years. I knew nothing about her in real life, but she became a powerful figment of my imagination. When I started writing fiction, I knew I would have to write about her. I also knew she was more than a short story. She needed a novel.

In writing Addie, I fleshed her out with details from my own life. The paisley skirt she wears in the rooftop scene? Mine. A favorite from the eighties. I loved that skirt—so soft and billowy; it made me feel like I could float away.

I think one reason readers may think Addie is you is that you’ve conjured her so powerfully. The narrative arc of your novel is strong and compelling but what is most vivid for me is Addie’s interior life. It’s a difficult path to follow as a writer: going deep into the character at the same time that you offer enough drama to propel the story forward. Did you find this path to be an organic outcome of your writing or did you craft the novel in this direction?

I think one reason readers may think Addie is you is that you’ve conjured her so powerfully. The narrative arc of your novel is strong and compelling but what is most vivid for me is Addie’s interior life. It’s a difficult path to follow as a writer: going deep into the character at the same time that you offer enough drama to propel the story forward. Did you find this path to be an organic outcome of your writing or did you craft the novel in this direction?

The story developed organically, scene by scene. The first scene I wrote was the rooftop scene, in which Addie delivers the news to Roland that she’s pregnant. I let that scene, and each one I wrote after that, tell me where to go next. How had the characters come to this pass? Where might it lead? Who could best tell that piece of the story?

Developing Addie’s point of view involved more intentional crafting—and also a sort of letting go. The events of the novel are so emotionally charged, I was afraid of overwriting Addie’s interior life. I didn’t want her story to become maudlin. In trying to be understated, I initially underwrote Addie. It took the advice of a good editor and an intensive, isolated period of rewriting to show me that I’d been shortchanging her.

I went to VCCA and for weeks, sat with Addie the way one might sit staring at a flower, waiting for it to bloom. I let myself see and feel into her situation as deeply as I could, without worrying about what emotions might come up, and wrote in as much detail as I could from that place. By then, of course, I knew almost everything about the events of the novel. What I was doing was getting to know and accept Addie in a way I hadn’t before.

Her point of view is represented throughout the book, but comes to light most clearly, I think, in her letters to Byrd. Those letters were always part of the book. They became a much larger part during rewrites.

I’m wondering how you came to know Emma Bowman, the protagonist in your novel. A Different Sun is many things—adventure, travelogue, love story, a story of strangers in a strange land. But—like you with Addie—I’m most affected by Emma’s interior life. She’s a complex, surprising creature: intellectual, spiritual, sensual. How did she come to life for you?

My novel is inspired by the actual diary of a woman from Georgia who went to West Africa as a missionary wife. Brief moments in that diary spoke to me: “feelings deeply wounded; have been sad all day.” And “this morning our dearest earthly possession took its flight; our dear babe is dead!” These moments were so compressed they seemed nearly to explode. If a young missionary wife wrote those sentences, what else did she leave out? Silences in women’s writing is a subject I have thought much about, being a student of Tillie Olsen, who wrote the book Silences: When Writers Don’t Write. With my novel I tried to write out the silences in the life of this character, to discover things she might have hidden even from herself.

I like your description of how you let Addie come to you at the VCCA. What most surprised you in her revelation?

I was surprised by the depth of her feeling for her unborn child during her pregnancy. She gives him her whole heart even though she’s choosing not to keep him. That’s a stinging cocktail.

I was surprised by the depth of her feeling for her unborn child during her pregnancy. She gives him her whole heart even though she’s choosing not to keep him. That’s a stinging cocktail.

It’s always gratifying when characters surprise me—that usually means they’re coming to life, sometimes in spite of me. I tend to be control-y, so it can be a challenge to get out of the way and let a character speak for herself. And to keep from arguing with her too much when she does. (I’m a lawyer, too, after all.)

I wanted my character, Emma, to have enough courage and humility to see and tell the truth of her situation even when the truth was uncomfortable. Your Addie does the same. What she tells is radical: that she gave up a child not for a career or because it was impossible for her to keep the baby but because it was her choice. It’s astonishing to me that you wrote such a sympathetic character and yet threaded that needle. It’s a huge accomplishment.

So is your writing of Roland. He is unattractive in many ways and yet we care for him. Tell me about the seeds for his character.

Haven’t we all fallen for a Roland? Some exotic, gorgeous, brooding musician who cultivates an air of mystery to hide the fact that he’s incapable of real closeness?

Patricia Henley taught me the importance of finding something to love in every character (at least every major character), even the unattractive ones. Otherwise they’ll be flat. Patricia went further. She said that becoming a good writer involves becoming a good person—learning, among other things, compassion.

I had to work hard at that to write Roland. He is, as you say, an unattractive character in many ways—self-absorbed, withholding. But Addie is drawn to something real and good in him: his music. And while he has trouble with women, he’s a surprisingly decent father. That’s not nothing.

I love the music in Byrd, in part because it’s music I shared, but also because your characters know so much more than I do—especially Roland. Music is almost a second language in your novel; it’s certainly an extended metaphor for the period you’re writing, so full of angst and hope, and a metaphor for Roland. The music expresses his emotional terrain in a way that the reader can share it.

Roland thinks in music. It’s his language; it’s the connective tissue that allows him to function in the world. Music is how he and Addie become intimate: he lets her listen to him practice. And he’s a gifted musician—not a show-off like so many rock-n-rollers, but smart. He understands how a song wants to sound.

There’s a lot of music in the book; there had to be. Music was part of the fabric of small-town life in the 70s. Where I grew up, it was our cultural capital. We were defined by what we listened to. We went to each other’s houses after school and played albums. We studied liner notes and lyrics. We harmonized; we worked out guitar parts. When I was in high school, one of my best friends moved into a new house with a formal living room that her parents couldn’t afford to furnish right away. The only thing in it—besides plush blue wall-to-wall carpet—was a console stereo. For us, that room was heaven.

You conjure that 70s teenage culture so precisely, though I was only on the cusp of it, coming to the U.S. from Nigeria at age 16 in the early 70s. I have to say, I really did think the music was autobiographical, given that you’re a songwriter, Kim.

You thought I wrote “Whipping Post”?

You know what I mean.

It was fun writing about this music—the music of my “formidable” years, as Roland would say. It was fun to think about these characters in relation to music. Roland, the privileged white boy lost in the blues. Danny, the rock-n-roll redneck who blasts Edgar Winter on the eight-track in his car.

Addie is a Joni Mitchell fan; her fascination is with words as much as music, and Joni of course was one of the most literary songwriters of the 70s. Addie is also drawn to Joni’s free-spiritedness, her worldliness. That fan worship takes an interesting turn when Addie learns that Joni, too, gave up a child.

One of the courageous decisions you make in the novel is a quiet one: you make Addie a bookseller. She chooses a humble but also noble profession, salvaging and selling old books. She lives close to books. How did you make the decision about Addie’s career? She stays with it for a long time.

Books are Addie’s way of understanding and relating to the world; that’s true for her from earliest childhood. Books are also her sanctuary. They make her feel daring and safe at the same time. It seemed inevitable to me that she would grow up to work and live among books.

Addie loves her work. She loves old books—their fragility, their musty smell, the history that comes with them, the people who congregate around them (a secondhand bookstore is a strange community).

I think it’s important for fictional characters to have jobs. I have respect for characters who support themselves, and I like to see how they do it—how they use their minds and hands. One thing I admire in your writing is how meticulously you describe your characters’ work, the physical detail of it.

Tillie Olsen always talked about work and cared about her characters’ work, whether in junkyards or shipyards or at home.

I spent serious research time on my characters’ work. They do more “hard work” than they might, Emma especially, because they move to West Africa. Actually I enjoyed using Emma’s physical labor as a metaphor for her enlightenment. At first she writes, sews, decorates, and teaches—all things she might have done in Georgia. As she moves further into the interior and becomes more African, she starts leaving off her undergarments, takes up pounding yam, and eventually takes her shoes off and gets into the mud pit with the other women to work up clay for building. It gave me a thrill to write that scene.

For me, one of the perks of writing Addie was that I got to spend a lot of time in secondhand bookstores without having to think of myself as a loiterer.

I enjoy field work—getting up from my desk, breaking my isolation, casting off my routine, doing things I otherwise wouldn’t, spending time with people who have something to teach me about the world. Turns out this is everyone. I find that people are almost always glad to be asked about their work. For this book, I got to learn not only about bookselling but also about astrology, mural painting, cocktail waitressing, gambling, and of course the music business.

For my next novel—historical fiction set in the 1920s—I’ve been learning about farming, natural medicine, mountain music, millwork, and union organizing.

One last question about music. If you were to choose a song from Byrd to serve as the novel’s anthem, which would it be?

That’s easy—“Till I See You Again” by Gladys Knight and the Pips, from the 1985 album “Life.” It’s a rich, textured, gospel-flavored song, shot through with loss and anticipation. The singer is saying goodbye, telling her friend she’ll miss him, she’ll wait for him, she’ll put her life on hold until he comes back. The vocals are plaintive and stirring, especially when the song modulates—the strings swell, the harp goes crazy, and the singers go into a sort of call-and-response that takes us to church.

I waited forever for the song to be released digitally. Fortunately, like Addie, I’ve held onto my turntable and all my vinyl.

* Kim Church photo by Anthony Ulinski; Elaine Neil Orr photo by Karen Tam.