Module: noun, a unit of information.

By the time graduate students make it to my class – Form and Theory of Fiction II – they are well-versed in narrative theory. Many of them have seen multiple teachers trace Freytag’s Pyramid on the chalkboard. They know about forward-moving plot, and they are certain that they understand how to structure a story so that a reader is drawn in, so that characters move through time and space in rhythm with the reader, so that there is an emotionally satisfying end to their nice, neat story. In short, they think they know how fiction ought to be built. It is, of course, not so simple. Knowing the beats of a good linear story doesn’t necessarily make it any easier to write one, but there’s a confidence that builds when you’ve stared at Freytag for long enough, an assurance that you know where all the pieces of a story ought to go.

I like to throw modular stories at them in an effort to curb that smug knowingness.

On days when it is warm enough, they take my daughter’s daycare class outside to play. There are slides and tricycles and strange, metal climbing constructs, but Erin tends to dig in the dirt. By the time I arrive to pick her up, her hands, arms, legs, and face will be smeared with the stuff. Even once I’ve wiped her clean with a wet rag, lines of dirt stubbornly remain beneath her fingernails.

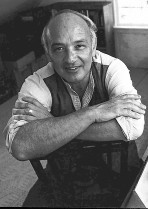

Rick Bass’s “The Fireman” is as static a piece of fiction as you’re likely to read. It is concerned with Kirby, a fireman. He is on his second marriage. Things are getting better, he is happy with his new life, but there is the nagging dissatisfaction with having ended his first life, with having left behind a daughter, a child he only gets to see once a week and every other weekend. The story is divided into modules that discuss the new marriage, the left-behind daughter, the fires he fights. Nothing changes with Kirby. There is no movement to the story, and there are certainly no epiphanies. There is just the steady build of those modules, all of them employing the same language. Words repeat in different contexts. Bats circle back to the chimney of a burning building, searching for their lost young. Meaning accumulates. Kirby’s life sits flat and still. Fire. Grace. Tunnel vision. A miracle.

Rick Bass’s “The Fireman” is as static a piece of fiction as you’re likely to read. It is concerned with Kirby, a fireman. He is on his second marriage. Things are getting better, he is happy with his new life, but there is the nagging dissatisfaction with having ended his first life, with having left behind a daughter, a child he only gets to see once a week and every other weekend. The story is divided into modules that discuss the new marriage, the left-behind daughter, the fires he fights. Nothing changes with Kirby. There is no movement to the story, and there are certainly no epiphanies. There is just the steady build of those modules, all of them employing the same language. Words repeat in different contexts. Bats circle back to the chimney of a burning building, searching for their lost young. Meaning accumulates. Kirby’s life sits flat and still. Fire. Grace. Tunnel vision. A miracle.

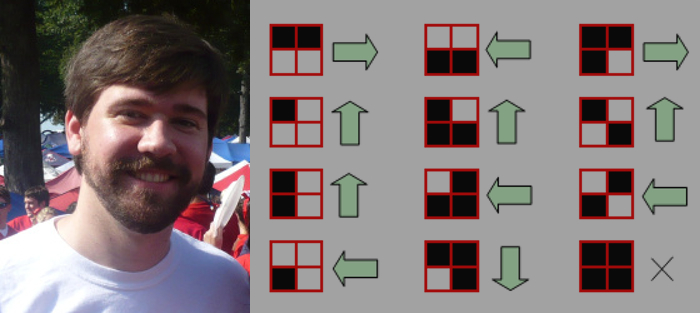

Modules: noun, plural units of information gifted to a reader and laid alongside one another in the hope that there can be an accumulation of meaning, a building and layering that might absolve a work of fiction of the necessity for forward momentum. This is particularly vital in stories centered on loss and trauma, where events themselves resist straightforward categorization. When meaning eludes us, we add and subtract, stack and build, until we’ve mosaicked our way deeper into the mystery.

The fingerprints of modular writing are, of course, all over good fiction in general. The repetition of language in another Rick Bass story, “Redfish,” functions in much the same way as that in “The Fireman,” though the former is linear and the latter is not. Juxtaposed flashback sections play a role in forward-moving novels, and at the end of the day, when we talk about scene selection in a linear story, we are really talking about the same method of organization that must take place when setting modules alongside one another. Just about every book on writing that I’ve read has some brief note telling us that the tags and categories we use to define stories and structures are not, in and of themselves, at all helpful when sitting down to write the damn things, but that never stops us from adding these labels. We like definitions. We like to stake out clarity in structure since, in good fiction, clarity cannot be staked out in content easily or at all.

Some months ago, another writer suggested to me that it was more painful for her to read failed modular stories from her students than it was to read failed linear stories. When I asked why, she told me that the problems with the failed linear stories were almost always problems that could be worked with or learned from. The problems with the failed modular stories were problems of intention. Many of those works, she said, came from writers intent on writing to the form, and the result was a slush of scene and image that could not be parsed and that the reader didn’t want to parse.

Bret Anthony Johnston argues in his essay “Don’t Write What You Know” that, “stories fueled by intentions never reach their boiling point.” That’s the fundamental problem that my friend saw in her students’ stories. They were fraught with intention, too absorbed with the necessity of fitting a form to feel organic and whole.

Poets have a good way of approaching this. If you view form as a tool to be used when necessary rather than as a mold to use when desired, you create a piece where the form echoes the content and not the other way around. At least then, even if your story fails, you’ve got something whole to work with.

File this one under Things I’ve Done That Can’t Be Explained:

In third grade, I sat beside the teacher’s desk, at the side of the classroom. When she stood in front of the chalkboard, her vision narrowed to the center of the room, and I, fidgety by nature, was left to my own devices, just outside her line of sight. I unfolded her paper clips, tore the corners off pieces of her paper, opened and closed and opened and closed her heavy, metal stapler. It was in the middle of that act, the opening and closing, that I slid my finger between the two pieces of hard metal, pushed down, and intentionally sent a staple into my skin. I didn’t cry out, though tears welled in my eyes. I pulled the staple out, wrapped my finger in a sheet of notebook paper to staunch the bleeding, bit my tongue to hold it all in.

Slow building repetition is often a part of modular writing. Think here of Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, where we see the image of a slim, dead, dainty young man enough times that when the full scene is laid out in all its horror, O’Brien doesn’t even need first person to let us know what his narrator experienced in the killing moment and in the long hours after.

The golf tee sat wedged between concrete and grass. Upside down, head buried in the dirt, its pointed tip stuck an inch into the air, waiting. It slid very easily – like a nail – right through the sole of my shoe and into my foot, that sharp head coming to rest a half inch deep. The dirt held it so firm and straight, when I pulled my foot away in pain, I had to tear it from the ground. At the hospital, they gave me the tee. It had once been a rich, dark green, but by the time I held it in my hand, it was scuffed and scratched. I had to wash the dirt from its surface.

Tony Earley’s “The Prophet From Jupiter” pushes the natural fragmentation of the modular structure to its outer limits. The modular units of most stories are paragraphs, strung together and separated by space breaks. Earley denies the reader the ease of that kind of compartmentalization and insists upon modules at the sentence and word level. The story becomes such a jumble of information, students often balk at it within the first three or four pages, not understanding that there is meaning in chaos if the chaos is organized well enough. By the end, most students are on board, even if they can’t figure why the things they disliked about the early pages are the things they value in the full story.

The little round scar at the center of my heel is my most recent, but there have been others. A straight line along the inside of my middle finger, a memory of the jagged metal that hung fringed from the bathroom door in a Birmingham mall. A crescent on the top of my foot, just below the ankle, from the sharp underside of a swimming pool ladder. One you can’t see, round and aching and full, left behind during my third grade year when my father died. I don’t remember the funeral, but I remember being graveside, remember the casket waiting to be buried, the hole already dug. Another that you can’t see: a thin line just below my lip, hidden by facial hair. My own teeth put it there when I, three years old, tripped over a mound of dirt in our front yard.

Modular Story: noun, a piece of fiction composed of isolated units of information. Modular stories rely on juxtaposition of image, action, dialogue, language, and idea more than on traditional plot structures. They repeat themselves. They accumulate meaning. Where traditional stories insist that meaning comes from movement, a modular story insists that meaning defies movement, that individual modules create understanding that otherwise escapes us. They shift from one subject to another, a slight-of-hand move that gets me every time I read “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried.” I can’t wait until my daughter is old enough for that one. She’s got the right temperament, even at three, for Hempel’s brand of unflinching humor. She’s not yet learned compromise, even in the face of danger. She’d jump from every high place, run her hands across each surface, step on each hard barb the world has to offer, if we let her. We hold her back from such dangers, though she strains against that holding. When I show my daughter the scar in my heel, she tells me I need a bandage, pushes a finger against the white tissue. Her nail, still so small, is caked with dirt.

Further Links & Resources

- Read Madison Smartt Bell’s craft textbook Narrative Design, which attempts in great detail to explain how modular storieswork.

- See “An Online Resource Guide to Freytag’s Pyramid“

- Read Bret Anthony Johnston’s “Don’t Write What You Know” at The Atlantic

- Read Christopher Lowe’s story “Offender” in Steel Toe Review and his collection Those Like Us