What do a poem by Yeats, a painting by a mad British artist, a neurogenetic disorder, some random remarks from friends, and a bizarre medieval legend have in common? They were the mental notes—the imaginary file cards—from which I constructed my novel, Come Away (Dzanc Books, November 2014).

In a long-ago interview, Vladimir Nabokov spoke of his eccentric method of preparing to write a novel: He kept a box of file cards, he said. Each time he had an image, a character, a moment, a sentence, an event that he believed belonged in the novel, he would write it on a file card. When the box was full of cards, he would start writing the novel.

I always liked that idea, though I have never been organized enough to keep a box of file cards. But I do jot down notes, and mentally file away images and ideas which I hope to put to further use (though often, I have no idea what possible use they might be).

I like to think of them as my imaginary file cards.

When my daughter Anna was 4, she had a minor accident which shouldn’t have—but did—cause huge cranial bleeding and landed her in the emergency room. Seven months and seven doctors later, she was diagnosed with the dreadful neurogenetic disorder Niemann-Pick C.

When my daughter Anna was 4, she had a minor accident which shouldn’t have—but did—cause huge cranial bleeding and landed her in the emergency room. Seven months and seven doctors later, she was diagnosed with the dreadful neurogenetic disorder Niemann-Pick C.

The stress and anguish this caused cannot really be quantified. One of the only things that assuaged my sad soul was re-reading poems I had once found beautiful or moving. William Butler Yeats, a longtime favorite, engaged me again in a way I had not anticipated. His famous poem, “The Stolen Child,” resounded in my thoughts for months, especially the haunting chorus “For the world’s more full of weeping/Than you can understand.”

That event—coupled with those words—was the first imaginary file card for Come Away.

Some years later, a neighbor, also the parent of a special needs child, admitted to me that when his son was diagnosed with autism, he felt as if the child he loved had been spirited away and replaced with a changeling child. That image too clicked with me—not so much that Anna or her neurologically different friends were changelings, but that the lore of the changeling, the tale of a healthy child stolen by fairies and replaced with some kind of alien being, seemed so clearly a folktale explanation of neurological impairment in children.

That observation was my second imaginary file card.

The process of writing a novel—of creating anything, really—is quite mysterious even to the one who is writing it. The Yeats poem and the observation about changelings put me in mind of my youthful enthusiasm for the mid-Victorian British craze for fairy paintings, and especially the work of Richard Dadd, who spent most of his life in a mental hospital (the infamous Bedlam) after killing his father. His masterpiece, The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke, which hangs in the Tate Gallery in London, had caught my eye in college when I was perusing a book about symbolist art. When I looked at it again, it somehow resonated with the idea of a secret world swarming with creatures we could not discern, creatures who were not the benign fairies of Disney confections, but might easily decide upon a whim to whisk your child away and replace her with a withered husk.

Yet another imaginary file card! So far, I had Yeats, childhood illness and disability, the creepy legend of the changed child, and the sinister unseen world of a fallen painter.

I should add here that I have always been fascinated by the supernatural, more as a metaphor for all we do not understand about the universe than as a belief system. As Woody Allen observes, “There is no question that there is an unseen world. The problem is, how far is it from midtown and how late is it open?”

So, when I read the review of a book cataloging unexplained mysteries, and discovered the tale of the Green Children of Woolpit—a greenish boy and girl who appeared in a medieval English village, claiming to have wandered there from a world inside our world—I was so smitten by the idea that I actually jotted it down to research for a future project.

OK, it was on a napkin, which I promptly lost, but the idea lingered as another significant (if imaginary) file card.

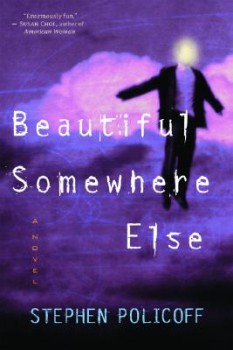

Around this time, I became frustrated with the novel I had been working on; I began to think about writing a companion piece to my first novel, Beautiful Somewhere Else (Carroll & Graf, 2004). Although BSE was largely ignored by press and public alike, the handful of people who did like it seemed especially intrigued by the interweaving of mordant domestic comedy with inexplicable events (alien abduction, mostly). I began to think that I was not done with this kind of interweaving nor with that novel’s characters (the narrator Paul, his wife Nadia, Nadia’s New Age philosopher father, Dr. Maire).

Around this time, I became frustrated with the novel I had been working on; I began to think about writing a companion piece to my first novel, Beautiful Somewhere Else (Carroll & Graf, 2004). Although BSE was largely ignored by press and public alike, the handful of people who did like it seemed especially intrigued by the interweaving of mordant domestic comedy with inexplicable events (alien abduction, mostly). I began to think that I was not done with this kind of interweaving nor with that novel’s characters (the narrator Paul, his wife Nadia, Nadia’s New Age philosopher father, Dr. Maire).

When I confided in a colleague about my unending anxiety over Anna’s health, my fear that she could be snatched from me at any moment, as in some dark myth, I was presented with my final imaginary file card: My friend said, “That’s the novel you should start working on.”

Reader, I did.

I cannot claim any profound lesson from my use of imaginary file cards or from the act of constructing a narrative out of random—yet somehow linked—ideas. As in Dadd’s vibrant painting, sometimes the most compelling moments in life happen along the margins of what we take to be important. I remain intrigued by randomness, by the shuffle of life’s deck, by the connectedness of that which appears unconnected. I try to allow what is simmering away in the background of my mind to inch its way into the foreground. Sometimes, it even seems to work.