Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

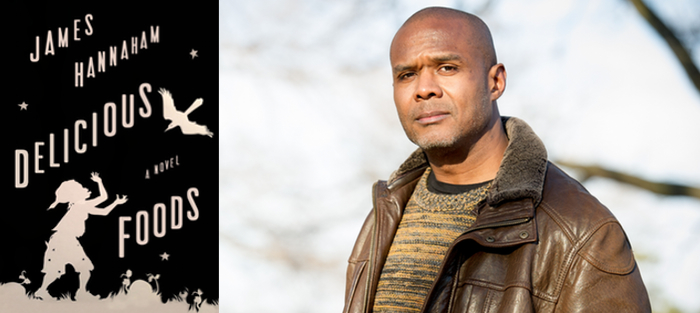

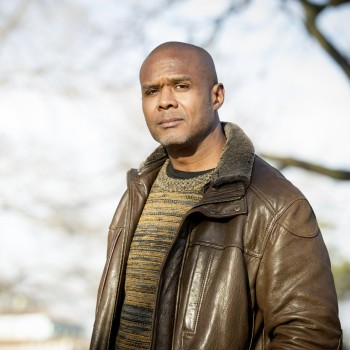

In today’s feature, Joshua Furst talks with James Hannaham about his novel Delicious Foods. The interview was originally published on March 16, 2016. Hannaham’s new novel, Pilot Imposter, was published by Soft Skull in November of 2021.

There are few writers alive whom I respect more than James Hannaham. His work is by turns lush and severe, baroque and spare, tender and perverse, intimate and worldly and always archly intelligent. He slips in and out of voices with the facility of a born mimic. He restlessly questions and subverts form, sometimes simulating existing templates—the artist statement, the review, and in his first novel, God Says No, the memoir—in ways that would edge toward pastiche if not for the ironic sincerity (or maybe, sincere irony) he brings to the endeavor, sometimes scratching out new forms to contain his meaning.

But to simply call Hannaham a writer is to delimit and misrepresent both his talent and his approach to art making. He is part of maybe the last generation of artists to hone their sensibilities in the renegade, cross-pollinating downtown New York art scene. Though his primary focus is fiction writing, he’s also done notable work over the course of decades as a conceptual artist, a critic, and a founding member of the internationally acclaimed theatrical provocateurs Elevator Repair Service. He teaches in The Pratt Institute’s unorthodox new Writing MFA program.

Hannaham’s new novel, Delicious Foods, is the sort of book that makes a career. It begins with the image of a black man named Eddie migrating north to escape the depravations he’s experienced in the south. The man has no hands—they’ve been brutally chopped from his body, the price he must pay to extricate himself from the indentured servitude of his earlier life—and his journey takes place now, not a hundred years ago. The story that follows attempts to account for how he got this way and why, while questioning how far America has truly come from the grotesqueries of slavery we like to believe are so far behind us. It’s also a love story between Eddie and his mother, a college-educated, politically-conscious woman named Darlene. And between Darlene and crack cocaine. In fact, much of the novel is narrated by crack, which in Hannaham’s imagining is a silver-tongued pimp named Scotty. Delicious Foods is that rare book that manages to grapple with history while remaining firmly lodged in the present.

James Hannaham and I have known each other for a long time and I was pleased to be asked by Fiction Writers Review to interview him. Here’s what happened.

Interview:

Joshua Furst: I suppose we should set this up. How do you want to do it?

James Hannaham: What do you think will yield the best results? The email interview is always sort of stilted and non- spontaneous, but often more thoughtful, and the in-person has to be transcribed.

We do live close enough to one another and are good enough friends that doing it via email would be pretty lame. Then again, it might be funny to do it entirely by text message or tweet or something despite those facts. We could text each other while in the same room.

Maybe the interview has already begun? Maybe that was your first question? And look! I have already begun to discourse on a philosophy that extends to my work, i.e., a belief that people respond to new forms, or new ways of presenting old forms, as much if not more than they do to new stories, or good stories.

You’re right. Our choice of interview mode will create subtle but possibly profound differences in your answers. I wonder, which James Hannaham do you think will show up in person and which James Hannnaham will be sculpting answers out of words? And maybe most importantly, which of the many James Hannahams do you want to present yourself as in this interview?

I’m trying to integrate myself a little bit more. Since you are friends with all of the James Hannahams (except, of course, my late uncle and my even later grandfather), you are perhaps uniquely qualified to unearth as many of those rascals as you wish.

I’m trying to integrate myself a little bit more. Since you are friends with all of the James Hannahams (except, of course, my late uncle and my even later grandfather), you are perhaps uniquely qualified to unearth as many of those rascals as you wish.

Maybe we should start with figuring out which James Hannaham wrote Delicious Foods? Did the same one who wrote the Eddie parts write the Scotty parts?

They’re all me. There’s that Fitzgerald quote from The Last Tycoon (which I only know because of Elevator Repair Service, amusingly), “Writers aren’t people exactly. Or, if they’re any good, they’re a whole lot of people trying so hard to be one person.” I think I took that to heart because I believed it to be true of myself. Creating characters has always been a kind of coping mechanism for me. I was born in the middle of a divorce, and as I got older it became a great strategy for me to distract and amuse my warring relatives by adopting various personae and making faces, particularly at my sister and my mother, who both needed a lot of cheering up at the time. But I was also buying myself some peace and quiet at the same time. So, win-win. If I’ve stopped you from crying, I’ve stopped you from crying. And that’s been kind of a theme throughout a lot of what I’ve done with my life, as I discovered that the skills I’d started out using to smooth things over in my family were useful in other contexts as well.

But that’s not exactly an answer to the question. I guess the answer is yes.

It’s interesting that, from an early age, you were thinking about how the way you presented yourself might please, amuse, distract, and otherwise provide relief for other people. There’s something both generous and self-protective in this. The more competing versions of you we see, the more we understand what unifies them. And, I find it fascinating that you developed certain of your aesthetic sensibilities out of a desire to “smooth things over” or “cheer people up.” I’d never associate you with social uplift, at least in the ways it’s been codified at this late stage. In your work, and especially in Delicious Foods, you use your amusing voices to disrupt and challenge the reader’s pieties. No matter how funny and magnetic Scotty is, he’s still crack cocaine and he will still kill you if he can. When and how did you begin to put your various personae to their own uses?

I’m not sure my thinking was that complicated at that age. One is too busy just surviving as a kid, testing things out to see what works.

Between the impulse to cheer up my family and Delicious Foods, there are at least forty years of thinking and schooling and reading and living to complicate that idea. My mother didn’t censor our reading as a child; so my sister and I naturally ran for the dirtiest books we could possibly find. That was my introduction to literature—William S. Burroughs and Anaïs Nin! De Sade! Nabokov! The Olympia Reader. Portnoy’s Compliant. Jean Genet. I still don’t trust a book if it’s not filthy in some way, if it doesn’t have the potential to offend someone, if not me.

I’m not sure that I have completely shed the idea that social uplift is part of my project. I’ve just tried to avoid going about it in a clichéd, familiar and/or artless sort of way. Social issues are fascinating and important and juicy to me, but my allegiance is really to art and truth—well, “truthiness,” anyway—and making people aware of some things they don’t want to face but must in a way that makes those things faceable. Or even, in a perverse way, enjoyable. But not purely enjoyable. Entertainment is one of the least interesting things that literature can do, but people seem to hold it in high esteem nevertheless. I’ve always preferred to be entertained in a rollercoaster sort of way by any culture I consume. You know it won’t kill you, but you might throw up.

How does this translate into issues of form?

I suppose that for all of my love of words, I enjoy accepting the “material” for what it is, and using it in the many ways that it works. I’m always aware that language can never quite say exactly what it needs to, it’s an imperfect delivery system for reality, essentially, and it conceals as much as it seems to reveal and can be used for all kinds of lying and half-truthing and obfuscation. Though I think those qualities can be horrible and fatal in real life, in literature they’re fun to mess around with. Hence a character like Scotty—although that voice didn’t come from so pedantic a place.

And of course, you spent a long time trudging around in the New York experimental theater scene before dedicated yourselves to fiction. How did these untraditional paths affect your experience in grad school of the classic “let’s workshop our autobiographical realist short stories” workshop model?

Coming to fiction via art and performance, I had already built up a natural resistance to orthodoxies of all kinds. If you’ve cut your teeth on Richard Foreman and The Wooster Group and worked with David Herskovits, to say nothing of my time sharing the sheer brainpower of Elevator Repair Service, the idea of taking seriously the concept of “realism” will probably just make you laugh your ass off. By the time I went to grad school I was thirty-five, and well-formed enough that I felt impervious to a lot of the Best American / New Yorker story ethos. I also found it impossible to imagine a place for myself in Alice Munro’s world. How many stories by or about urban black gay men have those places ever published? Talk about a VIDA count, honey, those places are like, zeros across the board! I’d also met Susan Steinberg by that time, and immediately sought her out as someone whose work proposed new possibilities for fiction that the Normals could not invalidate out of hand just for being “experimental,” in part because of the intense emotional impact that is her stock in trade.

Given all this—the general conservatism of the publishing industry, the long odds of success for an urban, black gay man, the complicating factor of your inability, or refusal, to play into our culture’s expectations about what an urban black gay man is supposed to be—were you surprised by the excitement Delicious Foods garnered when it started making the rounds at the big publishing houses?

I’m still a little baffled. The book is so profane and violent and weirdly put together. I guess I was responding to a lot of things floating around in 2000s culture—torture, torture porn, dystopia fiction, fantasy novels—but in a way that could never be mistaken for any of those genres, and I assumed that that approach would be sort of disappointing to people. I was sort of thinking to myself, “Why do you need to invent a dystopia when there are so many real dystopias out there in the world already?”

I tried to make it the best book it could be, but that’s never a guarantee that anyone will get it or like it. And I’m skeptical of success anyway. When Americans say success, we always mean “money.” Often with undertones of corruption, conformity, and/or whiteness—not things I really want to be associated with, to say the least.

We’re talking about literally ten days between when I turned in the manuscript and when we sold it to Little, Brown. I remember wishing that every writer friend of mine could have the experience of talking to publishers who were fighting over their book. The fawning didn’t always seem deserved, or even real, but it sure beat the one-line ding letter. Especially the one-line ding letters I was accustomed to getting from universities in, like, Oregon that I’d forgotten I’d applied to for teaching jobs with 4/4 loads.

Did you want to talk about being in school and balancing your terms for art against the prevailing “normal” expectations of the MFA? How to get their approval without compromise?

In grad school I was so wary of the pressure to conform to the vague standards of normal fiction that I acted out whenever I could. But as you know, any writing professor worth his/her salt is likely to be *starving* for something unusual to discuss in workshop. In Joy Williams’ class, I once turned in a story that consisted of a re-constituted file of various letters, out of chronological order, concerning the bequest of an abusive parent to a well-known charity. She really liked it, but Joy is a legendary odd bird. I turned in another story written entirely in what I called “Alzheimer talk” and got really great, useful feedback from Elizabeth Harris. For the most part, my professors didn’t discourage risk-taking, and my classmates didn’t police each other’s aesthetics. We were all tilling our unique little plots of literary land.

How did those experiences—both that of being a student at UT [the Michener Center at the University of Texas at Austin] and the years of trying to land a secure job—affect the way you approach teaching?

I started out teaching with the notion that writing itself wasn’t necessarily teachable, but I wanted to figure out what habits or ways of thinking could help someone approach the problem of writing effectively.

So I tried to come up with a kind of Suzuki method that would force my students to address directly the most basic elements of good fiction or story. I gained a lot of experience with student fiction and analyzed the sorts of bad habits most commonly associated with stories that didn’t work. And what I eventually realized was that beginning writers have a tendency (maybe an anxiety of influence kinda thing) to try to compose beautiful imagery and to turn clever phrases without paying enough attention to clarifying context (especially not in the oblique way I prefer) and—surprise!—all but ignoring narrative. So I’d start the semester by insisting that my students imitate the style of a police blotter as closely as they could while writing a few short pieces, and then I gradually weaned them off that style, first in terms of subject matter, and then I’d suggest that they amp up the lyricism a tad while trying to maintain the police-blotter level of reporting and frankness of voice. The most recent time I taught this way, I got the sense that it had a huge effect on my students and their writing. They really seemed to love it.

As for the job search—I’m not sure that I let it affect the way I taught. One of the few pleasures of adjuncting is that you usually don’t have someone breathing down your back and evaluating your classroom manner every day, so you’re more or less autonomous. I did gradually start to talk a bit more openly with my students about the plight of most of their profs who were adjuncts, because I got tired of perpetuating the myth that all professors were full-time, full-benefits employees unworthy of student sympathy.

Do you find that your teaching feeds your writing in any productive way?

Mostly in that I feel as if I have to walk it like I talk it. Having to explain your thinking about fiction writing is really helpful to shore up your own understanding of what the hell you’re trying to do, because as many classes or workshops as you might take, you’re truly on your own when you try to write that first novel. I mean, you’re pretty much lost in the wilderness and nobody gives a fuck—even the people who say they give a fuck don’t give a fuck. Even if they actually care, they can’t care enough to do it for you. The stakes just aren’t as high for anyone but your sorry ass.

Any idea what direction your work might go in next?

Any idea what direction your work might go in next?

I do have some idea about where I might go next, but I have to work in secret for a while before I can say anything about the substance of what I’m working on. I didn’t say a word about Delicious Foods for about four years of working on it. That was just the rule it wanted me to follow. The work needs to be exclusively mine for at least a little while.

It seems like I’m working on art these days. I started renting that studio that I can do both writing and art things in, and once I got done with DF, I started going in there and making a mess. I bought a vinyl cutter from these Hasidic guys over by Pratt and so now I’m making these pieces I call “Lengthy Statements,” they’re long sentences—about 20 feet long—that wrap around the walls, mostly musings about art and the art world, but that could change.

Any last things you’d hoped we’d covered but couldn’t because I failed to ask you the right questions?

You didn’t really ask any questions about the story or the characters in the book. Was that deliberate?

Oh! Do you want to talk about the characters? About Darlene’s dual nature? About Eddie and the “Magical Black Man” trope that you were so conscious of in the writing of the book? I could ask some questions about the larger context for the story, about the relationship between the farm in your book and the real world. Would you like to talk about that stuff?

Aren’t you going to be getting those same questions in every single interview you do?

If you don’t want to ask me any questions like that, I won’t answer any. But I’m not yet tired of hearing those “How much of this is true?”-type questions.

By all means! Answer those questions about the characters! And about the troubles in Florida!

Nah.

How do you think this interview would have gone if we’d met up and talked face to face? Would a different James Hannaham have shown up?

I’m the only one left, so I hope not!