As the director of a creative writing program, I receive a lot of books in the mail, from Best Poetry Anthology Ever to How to Write Your Novel without Tears, and yes, I made up those two titles. Most are well-intentioned, even the ones that seem less like craft assistance and more like therapy. As it happens, I’ve published a wide array of words myself (full disclosure: I’m a shameless eclectic who’s written everything from novels to doggerel verse to literary criticism and worse). And because I’ve been teaching creative writing for over two decades, people occasionally ask me whether I have any intention of writing a textbook. My answer used to be no, not because I had nothing to say but because many other writers had said it already, whether on notions of plot continuity or how to rig up a convincing character in a paragraph.

As the director of a creative writing program, I receive a lot of books in the mail, from Best Poetry Anthology Ever to How to Write Your Novel without Tears, and yes, I made up those two titles. Most are well-intentioned, even the ones that seem less like craft assistance and more like therapy. As it happens, I’ve published a wide array of words myself (full disclosure: I’m a shameless eclectic who’s written everything from novels to doggerel verse to literary criticism and worse). And because I’ve been teaching creative writing for over two decades, people occasionally ask me whether I have any intention of writing a textbook. My answer used to be no, not because I had nothing to say but because many other writers had said it already, whether on notions of plot continuity or how to rig up a convincing character in a paragraph.

In my creative writing courses, I tended to rely on short material, which I found both pedagogically useful and convenient. Given the all-too-limited interval of a workshop, with brief narratives, we could discuss three diverse stories in the same time we’d take for one longer story, and with a good prompt, I’d be looking over fifteen two-page stories rather than just as many seven-pagers. Around the mid 80s, this short-form fiction got a boost from Robert Shapard and James Thomas’s anthology Sudden Fiction: American Short-Short Stories, which featured Donald Barthelme to Tennessee Williams. Tom Hazuka, Denise Thomas, and James Thomas’s Flash Fiction: 72 Very Short Stories came out in ‘92, and shortly thereafter the internet changed the world of flash as we know it. The web proliferated flash fiction, as it does with everything from news to commerce—but with one gap. There really wasn’t a textbook devoted to flash fiction. Rose Metal Press came out with what it termed a field guide to the form, and though it’s got some neat stuff, it’s basically a series of author interviews. In the last few years, a couple of books have advertised themselves as flash guides, but they mainly start talking about flash fiction and soon veer into general lessons about how to write well.

So about three years ago, I started making notes for a book that would teach people how to write flash fiction. I’m not into the zen of writing or the wonder of it all, though I recognize the value of cheerleading. What I want in a textbook are nuts and bolts, elements of craft. To truly help flash fiction writers, I wanted every chapter devoted to a particular kind of story, some technique or form that worked well in a small space. I started with the vignette, from a column I had written for The Writer on the subject. I moved on to the dialogue, the character sketch, the rant, the flash fiction posing as a letter, and so on, but also prose poems, fables, even anecdotes, and my favorite, the what-if premise. I’ve just been told that the world will end in half an hour. What will I do in that period? (I still use a variant of that prompt for a nanofiction exercise, which dictates 140 characters or fewer to complete the story.)

When I had an outline and some sample chapters, I prepared a pitch letter. An editor at Macmillan liked the idea but thought that people were ripping off rather than buying textbooks these days. Someone at W. W. Norton said yes, then no. But Columbia University Press asked to see more, and after a lot of back and forth, that led to the submission of the whole manuscript. The book went through not just two but four reader’s reports and many revisions, partly because many other writers have good suggestions, and everyone has opinions.

When I had an outline and some sample chapters, I prepared a pitch letter. An editor at Macmillan liked the idea but thought that people were ripping off rather than buying textbooks these days. Someone at W. W. Norton said yes, then no. But Columbia University Press asked to see more, and after a lot of back and forth, that led to the submission of the whole manuscript. The book went through not just two but four reader’s reports and many revisions, partly because many other writers have good suggestions, and everyone has opinions.

One aspect I labored over (so it wouldn’t seem labored over) was the tone. I wanted to include humor to offset the earnest nature of too many instruction manuals. I wanted to include fun prompts that would get people excited, like writing a dual viewpoint piece that veers from who’ll take out the dog to the topic of mortality. I wanted to include flash samples that students would actually enjoy, since some anthologies don’t even break the 50% rule, that the average reader likes over half the stories. Gaining permission to reprint the stories I wanted took a long time, since some of the authors were dead but protected by tough agents, some involved translation rights, others involved a welterwork of print and electronic rights, or US, Canadian, and United Kingdom rights, and on and on. And it all costs money—as it should, since I believe in paying writers for their work

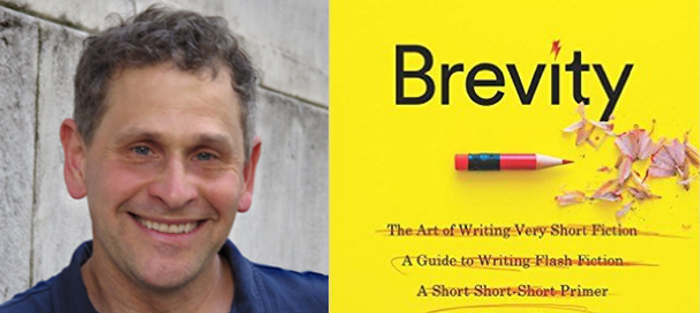

And now, three years after its inception, Brevity: A Flash Fiction Handbook is out, with a flashy cover and some very kind blurbs on the back cover. The term handbook instead of textbook was the editor’s idea, on the assumption that people don’t love that last term, and he may be right. But I do hope it’s as useful in the classroom as it may be to individual writers plugging away.

Here, an excerpt from David Galef’s Brevity: A Flash Fiction Handbook

How to Make Fiction in a Really Small Space

In 2012, the British newspaper the Guardian posted “Twitter Fiction: 21 Authors Try Their Hands at 140-Character Novels,” with results by novelists ranging from David Lodge to A. M. Holmes. Some writers have also attempted serialized stories via tweets, but the results don’t always fit into even flash fiction space constraints. In any event, nanofiction isn’t exclusively a cyber-age phenomenon.

“The Dinosaur,” by the Spanish author Augusto Monterroso, published in 1959 and translated by Edith Grossman:

When he awoke, the dinosaur was still there.

Here, two tips and a prompt for writing nanofiction:

Leave the ending open to suggestion. Just set up the premise, and let the reader fill in the rest.

Here’s an example by David Galef:

The night my father died, he was having trouble breathing, terrified. I held his hand and told him I’d return in the morning.

Here I am.

Variations on a theme: if you build on a known context, such as Little Red Riding Hood, you need only a few words to tie into a full-length narrative, or a news story that everyone remembers years later.

Here’s a variation on a well-known fairy tale, by Daniel Galef:

It turned into a prince, like it said, but its lungs were still on the metal tray, and it still stank of formaldehyde. I wiped my mouth.

Where can you go from here? All the humans on Earth will change into ferrets a minute from now. What will you do in that time? Write your answer in no more than 140 characters

Adapted from the “Vanishing Point” chapter in Brevity: A Flash Fiction Handbook, by David Galef, published by Columbia University Press (plus two samples of nanofiction by Galef & Galef)