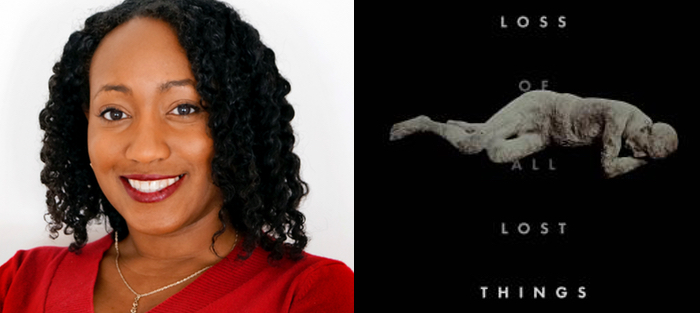

In less than a decade, Amina Gautier has established herself as one of America’s foremost short story writers. A recent winner of the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story, Gautier has published the prize-winning collections At-Risk (2011, University of Georgia Press); Now We Will Be Happy (2014, University of Nebraska Press); and The Loss of All Lost Things (2016, Elixir Press). In At-Risk, Gautier’s stories are thematically linked by young people navigating troubled childhoods, in Now We Will Be Happy, by bicultural relationships between mainland and island-born Puerto Ricans, and in The Loss of All Lost Things, by journeys of loss and rebirth.

Gautier’s work teems with life, is thrilling in its complexity and dimension. She whisks readers into packed cities, high school classrooms and quiet suburbs, to bodegas and bedsides. Gautier’s rendering of the human condition, whether it be through the loss of a child or lover, or the desire to find hope after tragedy, is captured with loving detail and immersive beauty. In Gautier’s “Now We Will Be Happy,” a meditation on the fried plantain dish tostones gives way to an elegant story about a woman recovering from a painful marriage who falls for a man who shares her love of Puerto Rican dishes. By the end of the piece, you too believe that “bruises can heal…and fall away…the way rain, gathered in the large folds of banana leaves, pours off in a rush when it has become too heavy to hold…” All of Gautier’s stories touch the heart. Her craft makes these tales of love and loneliness feel as if they are your own, and those of everyone you know.

The literary world has rightly honored Gautier’s talent. In addition to being a recipient of this year’s PEN/Malamud, Gautier has been awarded the Flannery O’Connor Award, the Prairie Schooner Book Prize, the Elixir Press Award in Fiction, the Eric Hoffer Legacy Award, the International Latino Book Award, the Phillis Wheatley Award, and the Chicago Public Library Foundation’s 21st Century Award. She has been the recipient of fellowships from the Camargo Foundation, the Chateau de Lavigny, Dora Maar House/Brown Foundation, Hawthornden Castle, Kimmel Harding Nelson Center, the MacDowell Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Woodrow Wilson Foundation. Her fiction has also been published in Agni, Blackbird, Callaloo, Glimmer Train, Oxford American, Prairie Schooner, and Southern Review, among other places.

Every time Gautier releases a new collection, I can’t wait to get my hands on it. Amina Gautier is an essential voice in contemporary fiction, and her work is not to be missed. In this interview, conducted via email, we discussed the art of crafting a short story, finding the right point of view, and writing about blame and moral ambiguity, amongst other topics.

Interview:

Jennifer Maritza McCauley: Congratulations on the PEN/Malamud Award! At-Risk, Now We Will Be Happy, and The Loss of All Lost Things are spectacular collections. Bernard Malamud, who the prize is named after, said of the short story: “…. A short story is a way of indicating the complexity of life in a few pages, producing the surprise and effect of…profound knowledge in a short time.” I’m struck by how you pack lyricism, searing emotional notes, and a superior handle on pacing and form into every single story. After teaching and studying literature, and writing stories prolifically, do you have strategies or go-to approaches when you face a blank page?

Amina Gautier: For starters, I never face a blank page. That’s simply too daunting to me. I typically write my first draft, or portions of it, the way I first learned how to write when I was young and poor—by hand, with a pen or pencil in a notebook, or on a notepad. That way, there’s no pressure. I’m simply scribbling, dabbling, recording bits and pieces. Later, I transcribe those bits and pieces, typing them into various word documents on my computer. Every so often, I add to the documents. It’s a slow process; I don’t write quickly, but I do write a lot. I work on multiple stories simultaneously in this manner, until I’m ready to focus on something for a stretch of time.

Eventually, I’ll think of one of those story drafts so long and hard that I won’t be able to get it out of my mind—I won’t be satisfied until I check in on it and see how it’s doing. So I open up the draft and—lo and behold!—I’ve got somewhere between 2500 and 4000 words to work with, so I go in and work with the draft, figuring out its beginning, middle, and end, writing its scenes, fleshing out its setting, until I find the story. Working in this manner prevents me from feeling any of the pressure I’ve heard other writers describe—for me, I’m simply working with something that’s already there and I’m just endeavoring to find its best form. I’d never write anything if I had to start with a blank page.

I’m less haphazard when revising, however. Once I’ve decided to devote my attention to a particular story/draft, then I’m obsessed. I’ll work on it day after day, for eight to twelve hours a day. I’ll start working on it when I wake up and, except breaking to eat, I’ll work on it until it’s time for me to go to sleep. Then I’ll turn around and do it all over again the next day, going through two or three drafts a day. During this time, I’ll be working scene by scene and I’ll never work on more than one scene a day so I can build the desired mood, rhythm and pace.

How do you define a successful short story?

A successful short story is one you read because you want to, because the subject matter is thought-provoking and its importance is buoyed by expert craftsmanship. Its attention to language and concrete detail make the story alive and visceral in such a way that when you close your eyes you can’t help but see the story. A successful story makes you feel that every single word and punctuation mark is serving the purpose of the story and being used to reveal meaning. You can read it on the page and hear it in your mind. A successful story is one that makes you feel that even its commas and em dashes had a job to do and they did it. A successful short story can take a little and make much. It can show you an entire world in a detail, an event, or an interaction that would normally be overlooked. It can capture the world for you and put it in the palm of your hand.

How would you compare the compilation processes of At-Risk and Now We Will Be Happy to The Loss of All Lost Things? Now that you’ve published your third collection, do you find the short story writing process easier?

I don’t find the short story writing process easy at all. If I did, I wouldn’t do it. Or perhaps I should say that when the process of writing short stories becomes easy, I will cease to write them. I write short stories because the process challenges me, keeps me on my toes, and never gives me a lazy moment. Each and every time it is a daunting endeavor to take all of what you want to say and refine it, and boil it down to its essence. To say what’s necessary with as few interactions, as few scenes, and as few words as possible—that’s quite the task!

As far as the three collections go, they were all compiled at the same time, so there was no difference in the way they came to be. In early 2009, when I was thirty-one years old, my fiftieth short story was accepted for publication and I thought that was a good time to stop and take stock of what I’d written. When I did so, I discovered that, with the exception of the short-shorts, my stories fell into four thematic piles. As I continued to write, those piles continued to grow, until three of those piles became At-Risk, Now We Will Be Happy, and The Loss of All Lost Things. I actually finished the stories for The Loss of All Lost Things before Now We Will Be Happy, but Now We Will Be Happy was accepted first. While Now We Will Be Happy was in press, I revised two stories in The Loss of All Lost Things and the collection was picked up just a few months afterwards, but we delayed publication for almost a year, just so the books wouldn’t come out on top of each other.

Your work often examines loss, and features characters in pursuit of safety, stability, and happiness despite their troubled circumstances. In the story “The Loss of Lost Things,” the protagonists grapple with denial after their child goes missing. They say: “Their misery was nourishing; they fill up on it…They prefer to live in limbo, in this new waiting world where they have not wronged each other…they do not have to be good people…as the parents of the lost boy they are entitled to a break…” In “Lost and Found,” after being kidnapped, a boy thinks, “He is lost but not the way he is taught to be …,” realizing the lessons he’s been taught by his parents aren’t always applicable to the horrors of real life. In “Palabras,” three generations of Puerto Rican men reflect on their relationships with their fathers, their lovers, and the loss of the island they left behind. Do you see loss and survival as unifying themes in your work?

I don’t know why I’m reading or writing fiction if not to learn how to be human, how to be more human, how to understand the human condition and the humanity of others, and connect to the humanity within all of us. That’s what I’m interested in. I’m not looking for a book to be “different” or “original” or to find “something I’ve never seen before” (especially since when people say these things about books, they simply reveal that they haven’t read widely or deeply enough). All of the stories have been written. They’ve all been told. So why are we still writing stories and why are we still clamoring to read them? I am doing so to understand my humanity, your humanity. To be human is to be vulnerable and the ways in which we yearn for the understanding of others while often trying to protect ourselves from being hurt is utterly fascinating to me. There could be a hundred million more stories about this human paradox of ours and they’d never be enough.

I’m interested in the “All” in the title of your third collection/short story, The Loss of All Lost Things? Why did you choose to include “All Lost Things” in the title or emphasize collective losses?

I never considered the title without including the word “All.” In addition to its thematic necessity, emphasizing all losses great and small, tangible and ephemeral, real and imagined, it is a linguistic necessity. Without the “All” the title would emphasize the “oh” sound i.e. The Loss of Lost Things that would then force you to over pronounce the “s” sounds as well and thus end up lisping, but the use of “All” creates an elision of “l” sounds between “All” and “Lost,” which is then followed by another elision of “t” sounds between Lost and Things, so the inclusion of the “All” elides three words and produces a continuous sound of loss.

I never considered the title without including the word “All.” In addition to its thematic necessity, emphasizing all losses great and small, tangible and ephemeral, real and imagined, it is a linguistic necessity. Without the “All” the title would emphasize the “oh” sound i.e. The Loss of Lost Things that would then force you to over pronounce the “s” sounds as well and thus end up lisping, but the use of “All” creates an elision of “l” sounds between “All” and “Lost,” which is then followed by another elision of “t” sounds between Lost and Things, so the inclusion of the “All” elides three words and produces a continuous sound of loss.

In all three collections, there’s a wonderful variety of POV and voices. How do you choose the right POV for your stories? Have you ever changed your mind on a POV mid-draft?

All the time. I change my mind about POV on a constant basis. I’m not interested in writing the same story over and over and I’m not interested in writing every story in my own voice, so I carefully make each POV selection for my stories. Because first-person seems to have now become a default choice for writers, I try to avoid it, unless the character’s voice and reliability (or lack thereof) become necessary to the telling of the story. This is one of the reasons my drafts of stories stay in the vault for so long—I often have to wait until I’ve figured out the right point of view and the appropriate level of psychic and narrative distance for the story. If I draft a story and it seems to work in two or three points of view, that means I haven’t found the right one yet, the one that says the story can only be told this way.

Tolstoy says: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” In many of your stories, families try to resolve cultural and generational gaps or overcome heartbreak—or they happen upon deception. Why do you think writers are interested in the conjuring of and deconstruction of the family unit? Why are themes of family interesting to you as a writer?

I’m unable to conjecture as to why other writers are drawn to writing about family, but themes of family are interesting to me because we all have or have had a family—whether it be a biological family, an adoptive family, a church family, a family we’ve assembled of close friends and/or colleagues, or fantasy families we’ve read about in books or watched on television and wished were our own. And, based on our happiness or dissatisfaction with those families, we’ve formed ideal notions of what families are and should be and how members of families should behave and we’ve measured how we and our families compare with our ideal. This, to me, seems the basis for as many stories as Scheherazade had nights.

In the story “The Loss of All Lost Things,” blame is a reoccurring theme. The protagonists obsess over the days their missing son is gone; they insist something or someone else is to blame. They wonder: “Whose fault is this? Who would do such a thing?” and think “blame is the glue that keeps them together…” Similarly, in your story “Push,” the idea of blame, after two girls get into an in-school altercation, factors meaningfully into the plot. And in “Most Honest,” there is a question of who is to blame for the burn-out of a marriage. Why is blame, or moral ambiguity, another thematic interest of yours?

I primarily write realism and what’s real is that we are human and no one wants to be at fault. If you can shirk the blame for something, then you can escape accepting responsibility or further action. If it’s not your fault, then you can abdicate responsibility for making a thing right. Admitting fault means accepting responsibility and, hopefully, taking action to reconcile or heal the breach. That seems to be an incredibly hard thing for people to do. Many have mastered the knack of the empty apology, the one that comes with no repentance or atonement. People apologize for mistakes and then blithely continue to make them. We live in a moment of constant surveillance, in which many people, celebrity and non-celebrity alike, consider themselves to be brands.

These two factors, along with others, create a culture of denial and false apology, sorry not sorry. People are not apologizing because they sincerely regret their acts of wrongdoing or because they feel remorse over causing another person harm. They are apologizing because they were caught on camera, tape, and video, and their act was shared and displayed, and they don’t want to lose financial security or damage their brand/platform/sales. If you can dodge the blame, you can absolve yourself of further action. So yes, blame, is a great interest of mine. It seems that everything we read, watch, see, or listen to shows us scores of people who are locked in lifelong battles of trying to recover from past hurts, people who are emotionally stunted because of a hurt caused by another, who can’t get past it or over it or heal from it or let it go because the other person denies it and refuses culpability, and as long the other person does so, the hurting person can’t obtain closure and healing.

These two factors, along with others, create a culture of denial and false apology, sorry not sorry. People are not apologizing because they sincerely regret their acts of wrongdoing or because they feel remorse over causing another person harm. They are apologizing because they were caught on camera, tape, and video, and their act was shared and displayed, and they don’t want to lose financial security or damage their brand/platform/sales. If you can dodge the blame, you can absolve yourself of further action. So yes, blame, is a great interest of mine. It seems that everything we read, watch, see, or listen to shows us scores of people who are locked in lifelong battles of trying to recover from past hurts, people who are emotionally stunted because of a hurt caused by another, who can’t get past it or over it or heal from it or let it go because the other person denies it and refuses culpability, and as long the other person does so, the hurting person can’t obtain closure and healing.

I think the ambiguity of blame is a distinctly modern problem in fiction, a problem that rears its head in twentieth- and twenty-first-century fiction in a way we didn’t see in much of nineteenth-century fiction (with the exception of Hawthorne). You think of Jane Austen’s novels, Charles Chesnutt’s novels and stories, George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss, Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, to name a few—it’s always very clear who is at fault, who has done an unpardonable thing, and who all are to blame for someone’s downfall, misrepresentation, or loss of opportunity. It’s not so easy to point literary fingers now and many contemporary characters have no desire to be bound by heroic ideals. For me to work with such blame-dodging realistically human characters invites an exciting measure of unpredictability into my stories, because you just never know what my characters will do.

There are so many killer openings and punch-in-the-gut endings in your short stories, as well as individual lines that go beyond the story itself: “Worse than mourning is the wait that never ends”; “It’s not like you’re the first girl to fall in love, you know”; “So frail, the new, new being…”; “Nelida lets her soul fly to her island across the ocean and take her where it will….”. Would you discuss how you shape and define your writing style?

I believe in making each word count. If a sentence isn’t going to serve a purpose, go to work, and accomplish a goal, then it’s not a sentence that gets to stay in my story. As I revise, I listen to the sentences in my head and if they don’t sound right (i.e., they don’t achieve the tone or pace I’m looking for), they have to go or be reworked until they do. You can always tell who doesn’t listen to their sentences when you hear a writer give a reading and there’s no beauty at the level of the sentence. When we go back to the foundations of literature, we have to remember that people were telling stories long before they transcribed them, so stories were always meant to have an oral/aural component. Stories, tales, were memorized, recited, chanted, and sung by bards, griots, and prophets.

As for openings specifically, I am ever mindful that readers do not have to read your work or finish reading it just because they’ve started it. I think we often forget this because of the workshop format, which does not allow you to stop reading a story just because you don’t like it or it has flaws. But that’s exactly what can happen outside of the workshop, in the real world. We don’t live in that long ago world where people composed literature and read it aloud to groups and gatherings of friends as a form of evening entertainment. We have TV and internet and cable and video games and Netflix and any other number of technological forms of distraction that make it unlikely that someone is going to pick up a book that he or she has not been assigned or compelled to read and wade into it and be willing to wait two hundred pages for it to become interesting.

And even if we had an abundance of those kind of readers, we don’t have those kind of book or journal editors who would pick up such a book. So, stories and books have to announce themselves as worthy of being read all the way through. I think the way to do that is to start out strong, from the very first sentence, to write in a way that reassures readers that you, the writer, know what you are doing and where you are going and assures readers that if they will just put their hands in yours that you will lead them safely to the destination. As far as endings go, well, you’ve always got to stick your landing! That’s what separates the professionals from the amateurs.

In addition to the PEN/Malamud, you’ve won numerous literary awards including the Flannery O’Connor Book Award for Short Fiction, the Prairie Schooner Book Prize, Crazyhorse Prize, the Jack Dyer Prize, and many others. Do you see literary prizes as motivational or validation of your important work?

While I don’t write stories in order to win awards, I do recognize that awards do important work—especially for marginalized writers of color based at small presses without publicity funding, like myself. Prestigious awards get your name out there and bring you before the eyes of the public readership. For me, literary awards are incredibly validating. We all write for different reasons, for different audiences and thus have various ways of measuring our success as writers, but I am first and foremost a writer who is a literary critic and scholar and, as such, I am writing not only for the mainstream reader, but also for my peers— for those fully trained in the study and analysis of literature. As a literature professor, I am deeply interested in the canon and am invested in ways of opening and expanding it to become more inclusive. Mainstream sales and commercial successes are all well and good, but many books owe their long lives to having been embraced and taught by scholars such as myself, having been identified and selected for critical analysis and serious study in literature courses in secondary and postsecondary educational settings, becoming the meat of dissertations, conference presentations, and scholarly monographs.

While I don’t write stories in order to win awards, I do recognize that awards do important work—especially for marginalized writers of color based at small presses without publicity funding, like myself. Prestigious awards get your name out there and bring you before the eyes of the public readership. For me, literary awards are incredibly validating. We all write for different reasons, for different audiences and thus have various ways of measuring our success as writers, but I am first and foremost a writer who is a literary critic and scholar and, as such, I am writing not only for the mainstream reader, but also for my peers— for those fully trained in the study and analysis of literature. As a literature professor, I am deeply interested in the canon and am invested in ways of opening and expanding it to become more inclusive. Mainstream sales and commercial successes are all well and good, but many books owe their long lives to having been embraced and taught by scholars such as myself, having been identified and selected for critical analysis and serious study in literature courses in secondary and postsecondary educational settings, becoming the meat of dissertations, conference presentations, and scholarly monographs.

Therefore, being selected for awards, by juries and panels of fellow literary experts, is indeed validating. It is even more validating for me to have received these awards since my books are considered atypical winners because they are short story collections from small, independent and university presses (i.e., not novels). It often seems that there’s an unspoken rule that only big books from major presses and books with large publicity budgets can and should win prestigious awards.

I’ve had quite a few people in the publishing world pity me and/or express regret that my books were published in small places because they assumed that my books would not have a chance to be noticed, or write me off because I’m not a novelist and haven’t subscribed to the short story collection followed by a novel formula they espouse, or who only bother to talk to me just to ask me when I’m going to write a novel. So I find that garnering awards is rewarding in the sense that it silences the naysayers and proves that the staying-true-to-yourself-and-your-artistic-vision method works just fine. More importantly, the validation that comes from receiving awards further gives hope to other writers out there who follow their own stars and corroborates what I have always believed, which is that excellent writing is excellent writing and that it will always have its day.

Are you working on any new projects?

I am always writing.