“The aim of literature,” Baskerville replied grandly, “is the creation of a strange object covered with fur which breaks your heart.”

—Donald Barthelme

On the wide sill near the table in our foyer where I write (and eat meals and do art projects with my daughter and anything else that requires a flat surface), an abstract structure sits below the window. The base is a roughly cut rectangle of foam board, that light yet rigid backbone of middle school science fairs and witty political protests. The two walls are constructed partly of foam board and partly of small scraps of wood cut into blocks and stacked into a pattern reminiscent of mid-century modern interior design. The foam sections of wall are braced at the base by more wooden blocks glued into L-shaped brackets. One of the columns of blocks is built, inexplicably, atop a flat gray stone that looks as if it were plucked from a riverbank. The roof is constructed of paper plates, scalloped around the edges and stacked four deep. A small red whelk sea shell stands on toothpick stilts fastened to the roof by—you guessed it—small wooden blocks. A string of plastic pearls is intertwined through a distended spring, one end of which sits in a puddle of dried glue. A sprig of polyester bluebells juts upward from the far wall. Two flaps of felt enclose the ends. And the entire thing is swathed in a crude coat of hot pink paint.

Anytime someone enters our house, their eyes are drawn almost immediately to this blazing apparatus. “Oh . . . my! What’s this?” they ask. One woman, who had once professed to me that she rejected perfectionism despite the fact that the books on her shelves were divided precisely by the color of their jackets, took one look, grinned, and remarked, “How . . . creative!”

The structure, a cat house built by my seven year old daughter, is an object that demands attention and invites questions. When my daughter brought the cat house home from an art class given by a retired potter friend of ours, I was stunned by the sight of it. It is not beautiful (though perhaps parts of it are), but there is something breathtakingly enticing in its grotesqueness, in its abstract geometry, in the unlikely engineering and faux ornamentation. I had no hope, of course, that either of our cats would recognize the thing, looking as it did like a piece from the Hirschhorn sculpture garden, as a habitat. Yet, nearly as soon as my daughter had set the house down, our older cat sniffed it over appraisingly, ducked her head through one of the felt flaps, and curled up inside. She proceeded to sleep in the hot pink cat house for weeks on end. My daughter’s creation had served its purpose, along with some other unintended purposes, and also filled me with an unexpected sense of joy. Our cat has since abandoned the house, but the house still stands on the sill near the table for me to gaze at frequently while I work. To me it is more than a child’s haphazard craft—but we’ll get to that later.

Like the cat house, strange objects in fiction act as powerful magnets for the reader. The use of concrete objects is a vital part of building the narrative world. Objects make fiction tangible. They become the physical details that we can see, smell, touch, taste, hear on the page, inviting us to engage in a more thorough participation with the text. When we read about a ceramic bowl filled with oranges or a fluttering windsock with the face of a Jack-o-Lantern, we are pulled more deeply into the story by our senses which can imagine the physical reality of these objects. Objects, too, serve as tangible representations of the intangible within a story. They can help direct us to what is not immediately obvious on the surface of the text. They can point us to the subtext. They can tell us about the characters who exist around them.

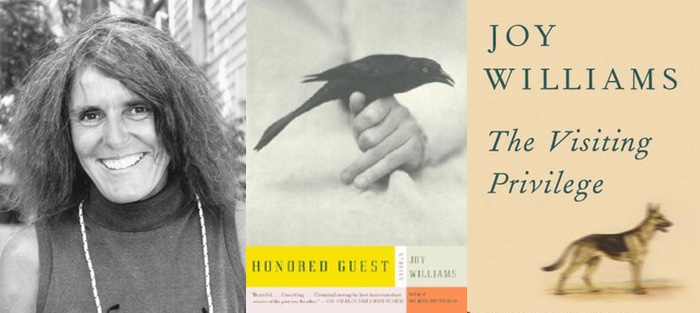

Strange objects in fiction, I would argue, go a step further. Strange objects, objects that exist beyond our expectations, do all the work of ordinary objects; but by making the imagination work harder, by requiring the reader to see beyond the everyday, they also create an even more thorough engagement with the text. In “Congress” by Joy Williams and “Sewing for the Heart” by Yoko Ogawa, bizarre objects play dominant roles. In both stories, strange objects serve to mesmerize the reader as well as the characters themselves. Their strangeness fixes our attention, drawing us with curiosity deeper into the narrative while also revealing more submerged themes within the texts and illuminating the characters around them.

1. I thought you’d like to make a lamp: Juxtaposition and Humor

Joy Williams’s “Congress” centers on Miriam, who, at the story’s outset, is living with Jack Dewayne, a revered forensic anthropologist who can identify from the merest fragment of bone the human entity which once possessed it. Miriam, however, has no discernible vocation. She reads from “overdue library books.” She steals sheets. She rescues wilting plants from the beds outside supermarkets and plants them in the corner of the yard. We learn: “She had become a woman who was still waiting for her calling.” From the beginning, the two characters are counterpointed. Jack is an expert, Miriam is a floater.

Joy Williams’s “Congress” centers on Miriam, who, at the story’s outset, is living with Jack Dewayne, a revered forensic anthropologist who can identify from the merest fragment of bone the human entity which once possessed it. Miriam, however, has no discernible vocation. She reads from “overdue library books.” She steals sheets. She rescues wilting plants from the beds outside supermarkets and plants them in the corner of the yard. We learn: “She had become a woman who was still waiting for her calling.” From the beginning, the two characters are counterpointed. Jack is an expert, Miriam is a floater.

The story takes its first turn when Jack’s student Carl—“an ardent hunter”—presents Jack with four cured deer feet. “‘I thought you’d like to make a lamp,’ Carl said.” Our attention is caught immediately by the absurd juxtaposition of the “four cured deer feet” and Carl’s nonchalant suggestion that they be made into a lamp. To Carl, the creation of the lamp seems to be a natural conclusion, yet to us the idea is preposterous. The effect of this incongruity is at once hilarious and intriguing.

Miriam feels intensely adverse to the idea. She tries to dissuade Jack from pursuing the craft: “‘You should resist the urge to do this, Jack, really,’ Miriam said. The thought of a lamp made of animal legs in her life and turned on caused a violent feeling of panic within her.” Not only does Miriam dislike the idea of the lamp, it fills her with “a violent feeling of panic.” Her reaction is intense and visceral. The emphasis on the thought of the lamp “turned on” being the catalyst of her anxiety suggests her fear lies in the reanimation of the parts. The deer feet will not just serve as a stand for a bulb; they will be electrified, imbued with energy, brought back to life. For Carl and Jack, there is nothing odd in this undertaking—it is simply a “hobby.” For Miriam, however, it is a Frankenstein-esque pursuit that fills her with terror.

Unmoved by Miriam’s visceral revulsion of the idea, Jack spends a weekend crafting the lamp. Once born to fruition, the lamp elicits yet another surprising response in Miriam:

Miriam, expecting to be repulsed by the thing, was enthralled instead. It had a dark blue shade and a gold-colored cord and a sixty-watt bulb. A brighter bulb would be pushing it, Jack said. Miriam could not resist the allure of the little lamp. She often found herself sitting beside it, staring at it, the harsh brown hairs, the dainty pasterns, the polished black hooves, all fastened together with a brass gimp band in the space the size of a dinner plate. It was anarchy, the little lamp, its legs snugly bunched. It was whirl, it was hole, it was the first far drums. She sometimes worried that she would begin talking to it. This happened to some people, she knew, they felt they had to talk.

Miriam is “enthralled” by the lamp. It seems to have some strange power over her—she cannot “resist [its] allure.” She stares at the lamp in an almost trance-like state of contemplation.

The lamp is drawn in vivid detail. Its description is vibrant with color: the “dark blue shade,” the “gold-colored cord,” “the harsh brown hairs,” and “polished black hooves.” The lamp takes on life through color. The repetition of the adjective “little” suggests something delicate, almost child-like about the lamp, with its “dainty pasterns” and “snugly bunched” legs. The language connotes something recently birthed, something small and precious and new to the world.

A complete description of the lamp defies concrete language. The lamp is “anarchy”—the electrified deer hooves resist the rules of how things should be. It is “whirl” and “hole” and “the first far drums.” Here, the rapt, mystical language not only expresses Miriam’s awe of the lamp, the lyricism of the language itself creates a rapturous effect on the reader, and, as we are awestruck by the swirling description, Miriam’s wonder for the little lamp becomes our own. The last lines of the passage foreshadow the evolution of Miriam’s relationship with the lamp as she worries she will “begin talking to it.” Through the vibrant details and Miriam’s magnetic reverence for the lamp, our curiosity is piqued.

Jack decides to take up bowhunting. We learn that “Miriam did not object as she might once have. Nevertheless, she could not keep herself from waiting anxiously beside the lamp for Jack’s return from his excursions with Carl.” As Jack and Carl begin to spend more time together, so too do Miriam and the lamp. Soon, the lamp begins to take on more humanistic characteristics: “Miriam and the lamp continued to wait solemnly for his empty-handed return.” No longer is Miriam simply waiting “beside the lamp,” now she and the lamp are “wait[ing] solemnly” together. Though subtle, this shift in language marks the lamp’s movement from mere object to active character.

Just as the lamp becomes more animated, Jack suffers a hunting accident, piercing his eye and brain with one of his own arrows. His injuries are catastrophic:

A month later, he could walk with difficulty and move one arm. He had some vision out of his remaining eye and he could hear but not speak. He emerged from rehab with a face expressionless as a frosted cake. He was something that had suffered a premature burial, something accounted for but not present.

Jack’s attempt at hunting leaves him dehumanized. His movements are stilted. He has only one eye, the use of only one arm. Like an animal, “he [can] hear but not speak.” We are told, with triumphant intonation, that Jack “emerged from rehab,” the word “emerge” evoking a sense of birth or bursting forth. This emergence is quickly juxtaposed, however, with the image of his face—“expressionless as a frosted cake.” The simile is both unexpected and aptly descriptive. The idea of a “frosted cake” carries with it associations of celebration, but also suggests an inanimate limpness. Despite the dire consequences of Jack’s accident, the surprise of the simile is humorous.

It is almost as if the reader is being nudged toward the comical irony of the accident—in his attempt to slay another creature, Jack has butchered himself; he has reduced himself to a “frosted cake.” Jack is no longer the man he once was. Now, he is “something accounted for but not present.” Here, the repeated use of “something” rather than “someone” is pointed. Jack has devolved from person to “thing.”

2. The lamp had witnessed a smattering of Kierkegaard: Anthropomorphism

As Jack becomes more object than man, the relationship between Miriam and the lamp grows in intimacy. We are told: “The lamp was a great comfort to Miriam in the weeks following the accident.” This statement is broad, suggesting nothing more special than a security object. The description, however, soon gathers momentum, and we see the lamp is no longer a stagnant, inanimate object to Miriam but something, or someone, much more:

But the crooked, dainty deer-foot lamp was calm. They spent most nights together quietly reading. The lamp had eclectic reading tastes. It would cast its light on anything, actually. It liked the stories of Poe. The night before Jack was to return home, they read a little book in which animals offered their prayers to God—the mouse, the bear, the turtle and so on—and this is perhaps where the lamp and Miriam had their first disagreement. Miriam liked the little verses. But the lamp felt that though the author clearly meant well, the prayers were cloying and confused thought with existence. The lamp had witnessed a smattering of Kierkegaard and felt strongly that thought should never be confused with existence. Being in such a condition of peculiar and altered existence itself, the lamp felt some things unequivocally. Miriam often wanted to think about that other life, when the parts knew the whole, when the legs ran and rested and moved through woods washed by flowers, but the lamp did not want to reflect on those times.

The lamp is described with succinct yet evocative language. The use of the word “crooked” implies something idiosyncratic; this lamp is an individual. “Dainty” suggests a sort of humanistic politeness, while at the same time the modifier “deer-foot” reminds us of the lamp’s animalistic roots. Now, beyond being a comfort to Miriam, the lamp is “calm.” It possesses its own emotional state. Miriam and the lamp read together, and the lamp has “eclectic reading tastes” and “cast[s] its light on anything.” We are told that “it like[s] the stories of Poe.”

Up until this point, it is possible to read the habits and tastes of the lamp as Miriam’s own. Of course the lamp will “cast its light on anything”—does a lamp have any choice in what it illuminates? It would be reasonable to believe that perhaps it is really Miriam who has eclectic reading tastes. Perhaps it is Miriam who likes the stories of Poe. Even the calmness of the lamp could be a projection of Miriam’s own state of mind.

This notion, however, is quickly contradicted when “the lamp and Miriam [have] their first disagreement” over a book “in which animals offer their prayers to God.” Here, the distinction between their tastes is clearly drawn. Whether in the world of Miriam’s imagination or otherwise, the lamp has become its own discrete entity, separate from Miriam’s own consciousness. Further, the lamp has matured by bounds since its initial creation. That the lamp finds the prayers “cloying” implies that its own tastes have grown too erudite for the book. At the same time, because it refers to animals—“the mouse, the bear, the turtle, and so on”—praying, the lamp’s dislike of the book may suggest the lamp has transcended its former state as an animal.

The lamp feels the author is “confus[ing] thought with existence,” implying that animals live in a state of existence absent of thought, a state of pure existence which the lamp has now left behind for its new “altered existence.” The lamp’s belief that “thought should never be confused with existence,” along with its “smattering of Kierkegaard,” exhibits a humorous loftiness, while at the same time broaching much deeper philosophical questions within the story. What does it mean to exist? Does thought make one’s existence more meaningful or valuable than the existence of one who does not (or cannot) think?

Despite the lamp’s advanced state, markedly absent is any evidence of the lamp’s own thinking. We are repeatedly told how the lamp “felt” things. Though the lamp seems to have grown intellectually, it retains an untainted ability to feel in an absolute way. This is highlighted by Miriam’s desire “to think about that other life.” It is Miriam who wants to think about the time “when the parts knew the whole, when the legs ran and rested and moved through woods washed by flowers.” Here, the image rendered is one of a deer running through woods; however, the wording also calls attention to the lamp’s amputation. The beauty and rhythm of the language serve to evoke an emotional response in the reader, a feeling of both freedom and loss, of truncation and nostalgia. The lamp, however, does “not want to reflect on those times.” It has passed from that plane of existence. It does not care to reminisce.

As the story goes on, Miriam grows more protective of the lamp and sensitive to its feelings. When Carl, who has moved in to care for Jack, wants to take a trip, Miriam’s only concern is for lamp: “The only thing she didn’t like was that the lamp would have to travel in the back with the luggage.” Here, the lamp is delineated from the “luggage.” It is not just something she will take with her, it is something which will “travel” itself. Before they embark, Miriam secures the lamp: “Miriam got a cardboard carton and arranged her clothes around the lamp. Her plan was to unplug whatever lamp was in whatever motel room they stayed in and plug in the deer-foot lamp. Clearly, this would be the high point of each day for it.” It is as if Miriam is tucking a child in for bed. The action is careful and tender.

Miriam constructs a “plan” for the lamp’s enjoyment of the trip. That the lamp’s illumination will “clearly” be the “high point” of its days shows with deadpan humor how thoroughly real the lamp’s emotional state is to Miriam. Miriam, without caveat, caters to the lamp’s needs as if it is a dear friend or even, perhaps, her child. At the same time, Jack is compared to “a large white appliance.” There is nothing human in his description. He is without thought or feeling or expression. His existence has become one of cold blankness.

3. She had skipped that cross-species eroticism and gone right beyond it to altered parts: Violence and Intimacy

As they drive, Miriam views her surroundings but remains conscious of the lamp in the back of the truck:

The land was vast and still there seemed to be considerable resentment toward the nonhuman creatures who struggled to inhabit it. Dead coyotes and hawks were nailed to fence posts and the road was hammered with the remains of lizards and snakes. Miriam was glad that the lamp was covered and did not have to suffer these sights.

Here, the term “nonhuman creatures” grabs the reader’s attention. A sharp line is being drawn between humans and all of the other creatures who must “struggle to inhabit” the land. Without being told explicitly, we can see from the context that humans are, of course, the source of this “resentment toward the nonhuman creatures.” The resentment exists despite how “vast” the land is. This vastness of the land increases the senselessness of the destruction Miriam views. There is space here for these animals. Their eradication is beyond reason.

The language suggests that the crimes against these creatures result not just from negligence—they are an outright attack. We see this in the creatures’ “struggle” to simply “inhabit” the land. To live has become a fight. The animals are “nailed to fence posts.” The road is “hammered with [their] remains.” The language is violent. With the image of this multitude of corpses, the story is injected with a sudden flash of gore. This is roadkill elevated to the homicidal. This is horror which supersedes simple human vice.

The language suggests that the crimes against these creatures result not just from negligence—they are an outright attack. We see this in the creatures’ “struggle” to simply “inhabit” the land. To live has become a fight. The animals are “nailed to fence posts.” The road is “hammered with [their] remains.” The language is violent. With the image of this multitude of corpses, the story is injected with a sudden flash of gore. This is roadkill elevated to the homicidal. This is horror which supersedes simple human vice.

Miriam’s thoughts are of the lamp. She is “glad that the lamp was covered and did not have to suffer these sights.” Here, not only do we see Miriam’s intense affection and protective attitude toward the lamp, we are also reminded of the lamp’s former state as a “nonhuman creature.” The lamp, too, struggled to inhabit the land. The lamp, too, suffered the violence of man.

We see Miriam’s instinct to shelter the lamp again as they read a book from a motel library: “The other book was about hunting zebras in Africa. I shot him right up his big fat fanny, the writer wrote. She had read this before she knew what she was doing and felt terrible about it, but the lamp held steady until she finally turned it off and got into bed.” Here, humor is juxtaposed with horror in a way that keeps us unsteadied and engaged. The colloquial voice of the hunter in the book and his use of the phrase “big fat fanny” is funny, however, Miriam’s reaction throws us into reverse and makes us question the seriousness underlying the humor. Why does Miriam feel “terrible” about reading the book? We learn that “the lamp held steady until she finally turned it off.”

By reading about the zebra hunter, Miriam has drawn attention to the lamp’s own experience of being hunted. The hunter’s casual, boasting tone—though initially funny—becomes instead careless and demeaning. Still, we are told that “the lamp held steady.” Despite the hunter’s idiocy and Miriam’s faux pas of reading the passage, the lamp is stoic. Once again, the lamp is characterized with dignity, existing in a state somewhere above crude humanity. Here, also, we see the psychic connection between Miriam and the lamp. It is not just the lamp’s light that exposes it to the insensitivity of the hunter, it is Miriam’s action of reading the words. The intimacy between Miriam and the lamp goes beyond companionship, beyond even any physical explanation; the relationship is spiritual, indefinable.

The truck stalls in a small town home to a “wildlife” museum curated by a revered taxidermist. Pilgrims flock to the museum to query the taxidermist. After plugging in the lamp in their hotel room, Miriam goes out to the Horny Toad, the town bar, and encounters some of the pilgrims. By the end of the evening, she finds them “all so desperate.” We are told:

Other people gathered around the table, all talking about their experiences in the museum, all expressing awe at the exhibits, the mountain lions, the wading birds, the herds of elk and the exotics, particularly the exotics. They had come from far away to see this. Many of them returned year after year.

The visitors’ “awe” of the museum is ironic. The animals are all dead. The creatures’ lives have been appropriated in order to create an experience of wonder—wonder of the natural world—for humans who visit the museum. The experience of nature has become a fabricated act of consumption.

The phrase “particularly the exotics” calls attention to the consumeristic nature of the museum-goers. The exotics are presumably rarer and more endangered, making them more desirable to view. However, the rarity of their breeds makes their lifeless effigies all the sadder. The animals have been hunted, carefully, with an attempt “not to mangle,” so that their forms can be preserved for the pleasure of these people. The people adore the animals, marvel at them, but give no thought to their former existence as living, breathing creatures.

Despite being put-off by the pilgrims at the Horny Toad, Miriam is eager to visit the museum the next day. After the bar closes, she returns to her hotel room and the lamp:

Miriam sat with the lamp for some time. The legs were dusty so she wiped them down with a damp towel. She was thinking of getting different shades for it. Shade of the week. Even if she slurred her words when she thought, the lamp was able to follow her. There were tenses that human speech had yet to discover, and the lamp was able to incorporate these in its understanding as well. Miriam was excited about going to the museum in the morning. She planned on being there the moment the doors opened. The lamp had no interest in seeing the taxidermist. It was beyond that. They read a short, sad story about a brown dog whose faith in his master proved to be terribly misplaced, and spent a rather fitful night.

This wonderful encounter is relayed in short, declarative sentences, expressing a sort of purity about the relationship. There is a sweet simplicity in Miriam’s actions. Like old friends, she and the lamp enjoy the act of merely existing near each other. The addition of “for some time” emphasizes how comfortable they are in this posture. Then, “she wipe[s] [it] down with a damp towel.” The act is intimate, recalling a mother wiping the face of a child. Miriam ponders “getting different shades for it,” as if she wants to dress it up.

The depth of the connection between Miriam and the lamp is revealed when we learn that “even if she slurred her words when she thought, the lamp was able to follow her.” The idea of Miriam slurring her thoughts is funny (she seems to be a bit intoxicated), but it also enforces the psychic connection between herself and the lamp. When we learn further that the lamp is able to understand “tenses that human speech had yet to discover,” we are directed again toward the mystical nature of their relationship and that other, higher plane that the lamp seems to inhabit. It has moved beyond the physical world of human speech, beyond, even, the metaphysical formation of thoughts in the mind.

Of course, the lamp has “no interest in seeing the taxidermist.” Of course, it is “beyond that.” Here, the meaning is double: the lamp is beyond seeing the taxidermist both because of its advanced state of existence, and also because it literally is beyond the point of taxidermy. The lamp’s former body cannot be preserved. Its legs have already been repurposed into a dainty accent lamp. The taxidermist can offer it nothing.

Miriam, on the other hand, is so “excited” to visit the taxidermist that she plans on arriving at the museum the next morning “the moment the doors open.” The description of her anticipation suggests something almost juvenile. The wording also hints at the consumeristic nature of the museum itself, reminiscent of a so-called door-buster sale.

Miriam’s interest in the taxidermist and the museum seems to cause a rift between herself and the deer-foot lamp. We see their differing views through the story they read together that night. The plot of the story, “about a brown dog whose faith in his master prove[s] to be terribly misplaced,” draws an immediate comparison to Miriam and the lamp. The “brown” of the dog recalls “the harsh brown hairs” of the lamp. Miriam, as caretaker, is associated with the dog’s “master.” Hence, the falling out in the story comes to represent a falling out between the lamp and Miriam. When the dog’s faith “prove[s] to be terribly misplaced,” we understand the letdown is twofold; it is not just a breach of fidelity, it is a fracture of the deep psychic relationship. This notion is supported by the “rather fitful night” that follows. The uneasiness is reminiscent of the disturbed sleep of quarrelling lovers.

Miriam arrives at the museum the next day. She bypasses the long line of pilgrims waiting to speak to the taxidermist, and the taxidermist, who in deific fashion has been watching her, invites her into his office for a private conversation. In the midst of their conversation, Miriam’s thoughts are drawn back to the lamp in the hotel room:

Back in the room, the lamp was hovered over Moby-Dick. It would be deeply involved in it by now. It would be slamming Melville like water. The shapeless maw of the undifferentiating sea! God as indifferent, insentient Being, composed of an infinitude of deaths! Nature. Gliding . . . bewitching . . . majestic . . . capable of universal catastrophe! The lamp was eating it up.

Here, Miriam’s contemplation becomes a vehicle for seguing to a broader contemplation of nature. Now, the lamp is able to process fiction without Miriam. We see the intensity of the lamp’s interaction with Moby-Dick, as imagined by Miriam, by its being “deeply involved.” Here, the word “deeply” also suggests a sort of submersion, as does the phrase “slamming Melville like water.” The word “slamming” immediately brings to mind the crashing of waves, while also connoting the consumption of alcohol. It is as if the lamp has been overtaken by the “undifferentiating sea” of the novel. It is drunk with Moby-Dick, who, as a hunted creature himself, shares a sort of kinship with the lamp.

The image is strange and humorous, but at the same time it digs to deeper points below the surface. Miriam is grappling with the sublime, contemplating the divine and its relationship to the natural world. The progression of excitement in the imagined scene is evidenced by the use of exclamation points. We can feel the acceleration of Miriam’s thoughts—the sea as God! God as insentient! God as Nature! Nature! And then: “Nature. Gliding . . . bewitching . . . majestic . . . capable of universal catastrophe!” Here is the antithesis of the “wildlife” museum. Here, nature is truly wild. It is awesome and beautiful; it is relentless and omnipotent. Here, in this museum of once living creatures, God as an “infinitude of deaths” has become a spectacle. The lamp has known this all along, and, now, Miriam understands as well.

The taxidermist explains to Miriam, rather abruptly, that he wants to retire and for Miriam to take his place. When Miriam hesitates, the taxidermist persists:

“No stuffing would be required. I’ve done all that, we’re beyond that. You’d just be answering questions.”

“I don’t know anything about questions,” Miriam said.

“The only thing you have to know is that you can answer them anyway you want. The questions are pretty much the same, so you’ll go nuts if you don’t change the answers.”

“I’ll think about it,” Miriam said. But actually she was thinking about the lamp. The odd thing was she had never been in love with an animal. She had just skipped that cross-species eroticism and gone right beyond it to altered parts. There was something wrong with that, she thought. It was so hopeless. Well, love was hopeless . . .

The taxidermist assures her that the “stuffing” is all done, that they are “beyond that.” This wording recalls the lamp’s dismissal of the taxidermist and his museum: “It was beyond that.” With the taxidermist’s insistence that Miriam would “just be answering questions,” this situation expresses a moving beyond the physical realm to one more abstract and metaphysical. The taxidermist’s macabre preservation of the animals in the museum is an act of creation. With the creation now complete, the taxidermist is ready to bequeath the answering of questions to Miriam.

When Miriam still hesitates, he asserts: “‘[Y]ou can answer them anyway you want. The questions are pretty much the same, so you’ll go nuts if you don’t change the answers.’” Here, the taxidermist’s comment, flippant on the surface, can be read with deeper implications. His words imply broader philosophical questions, questions like those raised by the story itself, on the nature of existence. Yet, he tells Miriam that there are no definite answers. The answers can be anything, limited only by the bounds of the imagination. New answers, in fact, are necessary to keep one from going “nuts.”

Once again, Miriam’s thoughts are not on the conversation but rather with the lamp. We learn: “But actually she was thinking about the lamp.” This repetition of her thinking of the lamp is both poignant, signifying their intimacy, and comical—it is still, after all, just a lamp. Although Miriam finds it strange that she has moved “right beyond it to the altered parts,” for the story it seems essential. What exists between Miriam and the lamp far transcends any coarse bestiality. The relationship, like all love is “hopeless”—baffling and consuming and inexplicable. At the end of her musing, the open punctuation of the ellipsis suggests Miriam’s surrender to the hopelessness of love. She is in love with the deer foot lamp—so be it!

In a last attempt to refuse the taxidermist’s offer, Miriam insists: “‘I have certain responsibilities . . . I have a lamp.’” Here, again, we witness the story’s wry humor. The line is laughable but also true. The lamp has become Miriam’s sole concern. The taxidermist coaxes her with the idea of all the animals she’ll have if she takes his place, of all the stories she’ll be able to make up about them. This seems to be the final nudge Miriam needs, for the story proceeds: “It seemed a pretty good arrangement for the lamp. Miriam made up her mind. ‘All right,” she said.” Here, Miriam’s final, conclusive decision is based entirely on the arrangement being “pretty good” for the lamp. It is this devotion to the little deer foot lamp that allows Miriam to advance from “a woman who was still waiting for her calling” into the revered, quasi-divine position of elucidating taxidermist.

The final passage of the story belongs, of course, to the lamp:

Miriam continued down the corridor and opened the door quietly to her own room. She looked at the lamp. The lamp looked back, looked at her as though it had no idea who she was. Miriam knew that look. She’d always felt it was full of promise. Nothing could happen anywhere was the truth of it. And the lamp was burning with this. Burning!

The paragraph is relayed in short, simple sentences. Miriam looks at the lamp and the lamp looks back at her. There is no sound. This quietude imparts a sense of suspense, moving the short paragraph onward, as if building toward something greater. The lamp looks at Miriam “as though it ha[s] no idea who she [is].” This lack of identification, however, is not negative; in fact, Miriam feels “it [is] full of promise.” By not girding her with its own expectations, the lamp allows Miriam to be whomever she wants. This brings us to the beautiful crux of the passage and emphatic conclusion. Here, nothingness becomes an open range, a wild field of possibility. Nothing is expansive and free and can “happen anywhere.” The lamp, who does not think but rather instinctually feels, is “burning with this.” The exclamation point after the final “burning” reads like an ecstatic whisper. The story ends in illumination with the burning lamp and the distinct feeling of openness and possibility.

Upon first reading, this final punctuation leaves us in a state of wonderful bewilderment. After inspection, the layers of the story unfold. We are made to question the value of existence and how humankind determines what forms of life carry value. We see the carelessness and arrogance of human destruction. For Jack and Carl, hunting—and the construction of the deer foot lamp—is simply a “hobby.” The taking of nonhuman life is a way to pass the time. The patrons of the museum, yearning for some sort of mystical experience, do not even acknowledge that the taxidermist’s animals are all dead. Humans here are blind consumers, ravaging these nonhuman lives, denying their existence.

These are intense ideas, ones that could easily cause the (human) reader to freeze into a defensive posture. Yet, somehow, we are not rebuffed. The strangeness of the lamp and the absurdity of Miriam’s affection for it are powerfully enticing. The peculiarity and humor of the situation draw us into the story and push us to read further. Williams is able to point to the grotesqueness of humanity, while the humor, absurdity, and tenderness of the little deer foot lamp shield us from feeling chastised. The reader is charmed and stunned into awareness.