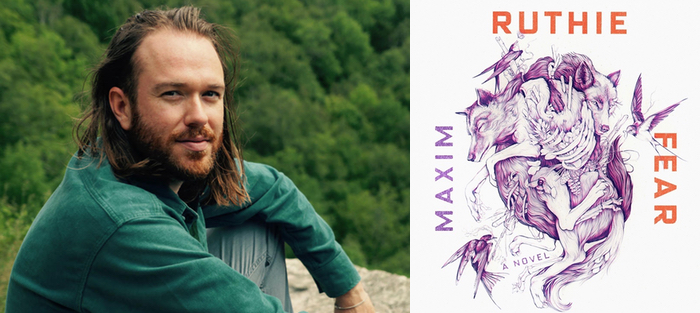

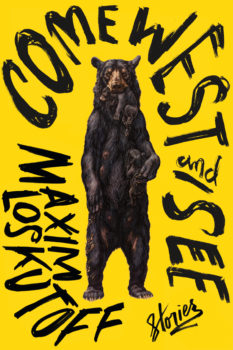

When Maxim Loskutoff’s debut collection, Come West and See, was published by W.W. Norton in 2018, it came to me for a review in this journal mainly because of a simple geographical fact: I’ve spent the bulk of my life in the big, sparsely populated western states on the map of America. It was a strong debut, full of the convoluted, self-conflicted characters that make deep, serious fiction go. (You can read the review here).

When I heard that Loskutoff’s debut novel, Ruthie Fear, was coming out this fall, also from Norton, I sought out an interview, because I knew I’d have a few questions. Loskutoff doesn’t write smooth, “easy listening” fiction. His work is bumpy and layered, like a mountain range with one kind of rock rising through layers of another. Love sticks out of the ground right next to violence. Beauty cuts a trail through the world that destruction paves over. Loskutoff’s characters are moved by tectonic forces shifting both within their psyches and throughout American culture, making them creatures simultaneously determined by their world and convinced that no one else will determine it for them.

Ruthie Fear tells the story of a girl growing into womanhood in the shadow of the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana. Her native territory is gloriously isolated from mainstream America in her youth, but by the time she nears thirty the spandex, lattés, and laptops have caught up with her as the Bitterroot Valley evolves into a getaway for wealthy west coasters. Ruthie’s life is dominated by her father, Rutherford, who lives in an isolated backwoods trailer and makes his living from odd jobs and what he’s able to hunt. She inherits—and eventually claims as her own—his stubborn independence, which verges on self-imprisonment in a vision of who she ought to be. Yet she also shares with him a palpable oneness with nature that, as she grows older, flies in the face of what her country is becoming. As Ruthie grows, and as her community changes, her desire to fit into the world takes center stage until nature returns with a vengeance.

Ruthie Fear is an untamed animal of a novel, and its ending will leave your head spinning. Loskutoff and I conversed via email from the opposite ends of adjoining states—me in eastern South Dakota, he in western Montana.

Interview

Steven Wingate: With Ruthie Fear, you moved from the short story to the novel—a different kind of race to run. Can you talk about how this transition between forms went for you?

Maxim Loskutoff: It’s very important to me to preserve the joy in writing. So many aspects of it are so hard: the solitude, the eternal questioning, living in others’ pain. I’m always seeking the light in the process and one place it comes is the challenge of trying something new. When writing short stories, I often set restrictions on myself, and in a sense the novel was a new kind of restriction. Every time my instinct was to go small, I would instead say “go bigger, go deeper.” And in that sense it truly was a joy. I loved going further with a character and a world than I thought possible. It opened up for me in so many ways, and Ruthie herself surprised me time and again. This is another kind of delight, and perhaps for me the purest kind, when suddenly the world on the page takes on a life of its own. That being said, the memory of short story writing is in the bones of this novel. I wrote it non-sequentially, simply writing whatever vision or situation the characters presented to me next, then in the editing process put it together along a timeline, so in a way it was like weaving together stories. The next challenge I’ve set for myself, in the novel I’m writing now, is to write it in order, with the plot devised ahead of time. Again, simply for the joy of trying something new.

Maxim Loskutoff: It’s very important to me to preserve the joy in writing. So many aspects of it are so hard: the solitude, the eternal questioning, living in others’ pain. I’m always seeking the light in the process and one place it comes is the challenge of trying something new. When writing short stories, I often set restrictions on myself, and in a sense the novel was a new kind of restriction. Every time my instinct was to go small, I would instead say “go bigger, go deeper.” And in that sense it truly was a joy. I loved going further with a character and a world than I thought possible. It opened up for me in so many ways, and Ruthie herself surprised me time and again. This is another kind of delight, and perhaps for me the purest kind, when suddenly the world on the page takes on a life of its own. That being said, the memory of short story writing is in the bones of this novel. I wrote it non-sequentially, simply writing whatever vision or situation the characters presented to me next, then in the editing process put it together along a timeline, so in a way it was like weaving together stories. The next challenge I’ve set for myself, in the novel I’m writing now, is to write it in order, with the plot devised ahead of time. Again, simply for the joy of trying something new.

Sometimes we have novels churning in our minds as our short stories come out. How long was Ruthie Fear churning, and what type of history does it have for you?

Ruthie the character has been churning for six years. I wrote a story about her in 2014, and she simply never left my mind. I thought I had finished the piece, but she had not finished with me. She kept coming back, speaking to me in the night, adding to and deepening her story, so in a way the realization that I needed to write a novel about her was very natural: she led me there. I often felt like I was simply dictating her words, she became that real to me, and my main concern in writing the book was doing her justice. The themes I had wanted to explore—gun violence in America, broken masculinity, the brutal, tragic history of the west which we try to cover up but which remains beneath the dirt—all followed naturally.

Many first novels are of the Bildungsroman variety and closely tied to the life of the author. You share a lot geographically with Ruthie, but there’s a twist to the typical Bildungsroman arrangement in that your protagonist is a girl growing into womanhood. How did this difference in gender affect your “deal with reality” as you drew on your own life and relationship with the region?

In a way, I was writing about myself and the men I grew up with, and one thing we very much lacked was self-awareness. It felt necessary to position Ruthie outside this masculine world, looking in. She’s able to see the men in the Bitterroot Valley much more clearly than they see themselves. And in the end she’s able to see them in context of their forefathers, the settlers who came and pillaged the land—the cycle of manifest destiny that leads to the culminating tragedy of the book. The conflict she feels, of loving these men and being a part of their world, while also wanting to destroy it to create something new, forms the heart of the book.

Your characters remind me a lot of Larry Brown’s—hardscrabble people at odds with the world around them. Is Brown an influence on you, or are their other authors in your family tree who you drew from in writing this novel?

Yes, I’ll just name three books I returned to time and again while writing Ruthie: Train Dreams, by Denis Johnson, which captures the entire tragedy of the west in 90 shimmering pages; The Almanac of the Dead, by Leslie Marmon Silko, which shows with knifelike precision how the sins of manifest destiny have led to the lost society we have today—a truly monumental work in every sense of the word; and Close Range, Annie Proulx’s Wyoming stories, which are relentless but also to me very funny, and capture the wild dreams of men and women in the rural west, and the lengths they go in their pursuit.

Montana has developed its own aura in the fiction world. So many great books have come out of there—Larry Watson’s Montana 1948, Debra Magpie Earling’s Perma Red, almost anything by Ivan Doig. Does Montana cast a shadow on writers, and if so, what’s it like? Are there Montana clichés you need to avoid?

Montana has a gravity. I grew up there always wanting to leave, to go to the city, the coast, where I thought culture lived. And I did, I was gone for fifteen years, but my writing never left. It only revolved around Montana closer and closer, until finally I was pulled home. So for me it’s less a shadow than a light, a source of endless inspiration. I don’t worry too much about clichés because to me clichés are often totems, something with a spiritual significance we don’t quite understand but find ourselves circling around time and again. I was once told that all Montana books have either a wolf or a bear, and my first two books certainly have, but that’s not something I want to avoid, I want to embrace it. Why do we keep returning to these images? What are they trying to tell us? What is it that we know on some deeper level, but are afraid to say?

The lyricism of this book is fueled by Ruthie’s intense supernatural relationship to the natural world. She grew up seeing the world as one living thing—a gift from her father, really—and maintains that even as she grows up and becomes accustomed to the world. I don’t want to make a too-pointed question here, but I’m curious about your relationship with this lyrical aspect of the novel.

It’s the most beautiful feeling I had as a child, and still have sometimes as an adult, wandering through the woods: the feeling of being part of something so much larger than myself, and the strange, powerful thoughts that accompany this epiphany. There’s nothing that’s more important to me to leave readers with than this feeling. I believe it is, not to sound hyperbolic, our only hope. To realize as a species that we are part of the natural world, rather than separate from it. And what freedom there is in that! What an overwhelming sense of calm, to feel a part of the entire breathing world, from long before you were here until long after you are gone. It’s a kind of nirvana, which Ruthie finds in the end.

Several of the stories in Come West and See foregrounded separatist, anti-government politics. Ruthie Fear has its own separate sociocultural concerns, particularly the overdevelopment of wilderness and the class discrepancies it causes. Why did you slide separatism into the background, and did it change the way you wrote?

Separatism has always been in the bloodstream in western culture, Montana in particular. My childhood was punctuated by the Freemen and the Unabomber, my adulthood by the Bundy occupation. Growing up here, these movements didn’t feel like outliers, they felt like the norm, part of the long outlaw tradition of fighting sheriffs, taking what you want, and fighting off everyone who would try to take it from you. That part of the western psyche still persists. To me, it has always felt like it will be our downfall. If we don’t go back and reexamine those violent heroes of our past, and devise a new mythology, one of worshipping the land and animals, rather than the men who slaughtered the bison and razed the forests, we are doomed. It’s a threat I’ve always felt looming in the background, so it only feels natural to have it in the work.

It’s no stretch to see Ruthie Fear as—among other things—an environmental novel. From that perspective, one moment in the book struck me: when young Ruthie wanders the wilderness and sees “what the men could not: that the wild land will someday cast them off.” How does awareness of environmental loss affect your work, and how does it affect the collective endeavor of contemporary literature?

It’s no stretch to see Ruthie Fear as—among other things—an environmental novel. From that perspective, one moment in the book struck me: when young Ruthie wanders the wilderness and sees “what the men could not: that the wild land will someday cast them off.” How does awareness of environmental loss affect your work, and how does it affect the collective endeavor of contemporary literature?

I think it’s the question of our times, and I’m often struck by the arrogance of the way we define it. I often hear language along the lines of “we’re destroying the earth.” No, we’re destroying our ability to live on the earth, but the earth will be fine. It was here for billions of years before us, and will be for billions of years after we’re gone. Again, we are part of something inconceivably larger than ourselves, and inevitably fleeting. No matter what we do, we will someday be gone. So for me it comes back to gratitude. Gratitude for the time we have here, for this miraculous harmony which supports us, the air we breathe, the food we grow, the rivers and lakes which sustain us. If we can shift our collective focus to intense gratitude for the moment we have, and attempt to share that moment with as many generations of our children that we can, we will have achieved our greatest aim. We were given one amazing gift: the ability to experience beauty, and now we are faced with the necessity of preserving the towering beauty of our environment. To me, all literature, contemporary and ancient, has had this goal: of showing readers beauty on the page so that they may more fully appreciate it in the world.