Joan Didion writes in The Year of Magical Thinking, “Grief, when it comes, is nothing like we expect it to be… Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life.” This intrusion of grief is relentless in Steven Wingate’s latest novel, The Leave-Takers; it is a novel ripe for pandemic reading and a gift of solace. The living and the dead are constant companions as protagonists Laynie and Jacob crash into each other and scratch their way to healing. Each carries heavy heartache through art, addiction, love, and hope. It’s the cracks in their sorrow that help each other see the light and the future they might make. The Leave-Takers is a modern love story and a compassionate road trip through loss.

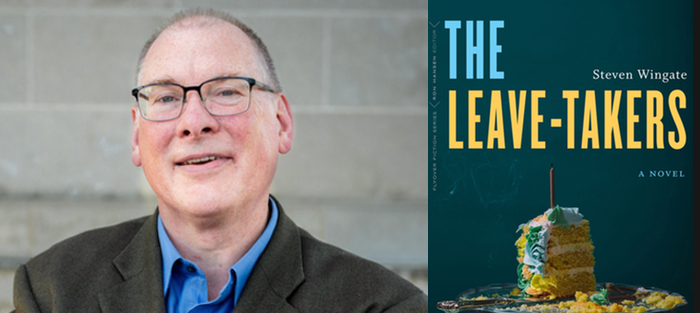

Steven Wingate is the author of the novels Of Fathers and Fire (2019) and The Leave-Takers( 2021), both part of the Flyover Fiction Series from the University of Nebraska Press. His short story collection Wifeshopping (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008) won the Bakeless Prize in Fiction from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. He has taught at the University of Colorado, the College of the Holy Cross, and South Dakota State University, where he is currently associate professor of English.

As fellow editors and devoted readers of Fiction Writers Review, it was a treat for Steve and me to join forces virtually for this conversation.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: George Saunders was on the Ezra Klein NYT podcast last week and spoke of revision as hearing the pitch of voices in your head. They were discussing the versions of you that show up for fiction writing. Does that resonate with you as a writer?

Steven Wingate: I’m all about the voices in my head, and fiction writing is one of the few callings in life that normalizes them. For most people, hearing voices is pretty scary. But if I wake up with a voice in my head, I know it’s going to be a great writing morning—I ride the wave of the voice and go where it goes. I’m not an analytical writer at all, which is one reason it takes me forever to write my books. My number one concern is whether the musicality of my sentences lays bare my characters’ emotional truth. Plot? Character arcs? They work themselves out if I follow the voices.

I’m thinking of the breadth of your novels and wondering if you wrote them in different spaces/places and whether that altered the work?

The Leave-Takers and my first novel, Of Fathers and Fire, were written in both Colorado and South Dakota, where I’ve split my time so far this century. Their physical setting of course influences how they turned out, but their psychogeographies are more important. For the first novel I dwelt in the land of teenage angst and spiritual confusion; for the second I dwelt in the land of trying to pull your life together before it’s too late. These psychogeographical circumstances naturally exposed me to different pitches of voice in my head, each with its own preoccupations. I like to think of them as radio stations. Writers have a whole range of stations playing inside us, and the ones we tune into shape what comes out on the page.

The Leave-Takers and my first novel, Of Fathers and Fire, were written in both Colorado and South Dakota, where I’ve split my time so far this century. Their physical setting of course influences how they turned out, but their psychogeographies are more important. For the first novel I dwelt in the land of teenage angst and spiritual confusion; for the second I dwelt in the land of trying to pull your life together before it’s too late. These psychogeographical circumstances naturally exposed me to different pitches of voice in my head, each with its own preoccupations. I like to think of them as radio stations. Writers have a whole range of stations playing inside us, and the ones we tune into shape what comes out on the page.

The way we show up in our own work was actually one of the first things I wrote about for Fiction Writers Review. Way back in 2009, I did a two-part essay called “Peering and Leaping into the Character/Author Vortex” that riffs on the Raymond Carver quote “You are not your characters, but your characters are you.” I think of my all characters, regardless whether or not they resemble me superficially, as petri dishes containing isolated strains of my emotional DNA that grow into other people. Discovering the shared resonances between us is the labor and joy of fiction.

Let’s talk about ghosts and their usefulness to the living. Jacob hosts his brother Daniel’s ghost and celebrates Deathiversary Day. Laynie writes letters to her lost ones and hears their voices woven with her own thoughts. When did the ghosts appear in the draft?

I can’t remember a draft without the ghosts, though their role strengthened over time. At first those ghosts—I focus mainly on Jacob’s brother Daniel and Laynie’s father Bill—felt like furniture for me, existing only to move the protagonists along. The longer I sat with the book, the more they came to have personalities and backstories, hopes and fears for those still living. I don’t put much stock in ghosts as an ectoplasmic phenomenon, but I do think the dead are present in our lives if we’re attuned to them. They live in us, some in a biological way. We carry our ancestors around everywhere.

The ghosts are as alive as the living and their haunting is welcome as a companion in grief.

Honoring the dead like Jacob and Laynie do is not just a way to stave off loneliness, but also instructive and guiding. The dead can act as an external super-ego that sees patterns and options in life that we can’t. They’ve “been to the other side,” so they naturally know more, and we often set them up in our minds to represent a superior wisdom. This guidance can be as simple as asking, “What would grandma think?” or as convoluted as the pretzels Jacob and Laynie twist themselves into with their ghosts. Consulting the dead in this way is an ancient human habit I find very lovely—not to mention formative for a great range of cultures.

As a Midwesterner, the road trips were comforting. The aimless wandering and watching of landscapes creates calm. Scenery rarely changes but then becomes suddenly violent through weather. Laynie’s road trips are a sprinkling of loved ones’ possessions to shed grief. She leaves behind cologne bottles, CDs, jewelry, books hoping that “someone could use them…someone could love them.” How is the road trip also a useful plot device?

I don’t think of myself as a Midwesterner so much as a Great Plains person, but I sure do love a road trip. They figure heavily in my life and in my fiction because they’re vehicles for discovering new possibilities and for self-examination, which are separate things that work best hand in hand when we’re trying to forge a new self. They’re great plot devices because they’re so fraught with potential change. But change usually happens slowly and our old selves always come with us. This makes the things we can’t change through the self-interrogation of travel as central to our stories as the things we can.

Migration, which is historically one of the most powerful forces in human culture, is a kind of road trip. Laynie’s cross-country journey with her father’s belongings turns out to be a migration without her even being aware of it. She takes off from LA not knowing when she’ll be back or where her trip will take her, and she’s ready to let herself change based on the result. She rolls the dice, and it ends up being the great migration story of her life. Later in the book, when she and Jacob take road trips together, they don’t simply want to leave behind the objects of the dead. They want to leave behind pieces of themselves that they know are getting in their way. Road trips are my favorite metaphor for self-renewal, probably because I’ve spent so long living in places where you have to drive hundreds of miles to get anywhere.

As Laynie and Jacob join forces, their grief dancing continues. They each remain in familiar rituals and patterns, often to their detriment.

I love that phrase “grief dancing,” and it makes me see my own work in a new way. The whole novel is about Jacob and Laynie learning to dance with each other, and it’s terribly awkward at first because they’re stuck in their own overly familiar patterns. They’re both broken records that repeat and repeat. Over the course of the book, they transition to new patterns of movement that are about each other and about life itself. By the end, they’re finally dancing about something other than their own grief. So, thanks for that metaphor!

I love that phrase “grief dancing,” and it makes me see my own work in a new way. The whole novel is about Jacob and Laynie learning to dance with each other, and it’s terribly awkward at first because they’re stuck in their own overly familiar patterns. They’re both broken records that repeat and repeat. Over the course of the book, they transition to new patterns of movement that are about each other and about life itself. By the end, they’re finally dancing about something other than their own grief. So, thanks for that metaphor!

How do you write characters with such compassion who are also sometimes frustratingly self-destructive?

Writing these kinds of characters with compassion is a result of constant exposure to them. I grew up around frustratingly self-destructive people, and in my innermost mind I fit that description perfectly (though my self-destruction is much subtler than Jacob and Laynie’s, and I play the role of Responsible Man in society reasonably well). Loving my characters is as crucial to me as following the voices in my head, and it’s my greatest obligation. If I love them and commit to seeing their joy and pain in the same light, then I can make them whole for readers. When I have a character who fails, it’s because I haven’t found a way to love them. I can’t stick with them long enough to understand how it feels to be them, so there’s no reason to think I can make readers understand that either. Those are the ones I let go.

They’re also wrestling with addiction and codependency. With so much heartache, is fusing a family futile, hopeful, or both? Maybe it’s the pandemic but I’m thinking a lot about our capacities as humans to hope and to be constantly crestfallen.

The pandemic is revealing so much about who we are and our capacity to endure, in addition to the incredible difficulty millions have in simply living. I really hope that when it’s over, we don’t just rush back to our old ways but instead reflect enough to see how little regard we’ve come to have for life in all its forms. Life isn’t a picnic, and heartache is always going to be with us. The big questions are whether we succumb to our personal heartache and whether we dismiss the heartache of others as irrelevant or somehow deserved.

Hope and crestfallenness are human constants, and we’re cyclical creatures in a cyclical world. Tide comes in, tide goes out. Breath goes in, breath goes out. How can we not accept that we’ve built our cultures and our psyches around those cycles? This is another aspect of the “grief dance” you mention—Jacob and Laynie, over the course of the novel, learn to accept their own cyclical filling and emptying without being afraid of it. They don’t expect to be hopeful all the time and they refuse to be crestfallen all the time. They grow toward accepting the vacillation between those two poles, even understanding their own interlocking rhythms a bit.

Recurring miscarriages is a specific grief Laynie and Jacob endure. How does this particular pain bond them or drive them apart?

Miscarriage, after addiction, is the other big “hopeful/crestfallen” dynamic in their lives. Wanting to have children and not being able to can be an existential crisis that causes you to question everything about yourself, and I remember that phase of my marriage too well. Our sons did not come along instantly. The hardest thing about miscarriages—whether they’re full-blown medical emergencies or unsuccessfully implanted embryos masquerading as late periods—is how they contribute to grief. Even if those embryos never “lived,” they’re still might-have-been people that started toward life but didn’t quite make it. I don’t know how much more of that phase I could have handled in real life, and I’m grateful that things turned around. We have two sons now, sixteen and thirteen, but I can still close my eyes and dial up the feeling of We’ll never have kids, will we? like it was yesterday.

The wanting is so palpable, but there is a sweetness, a gentleness in their shared pain. The longing is there too, both for children and for a place to escape from the desire. The potential to change their geographies unites and creates conflicts for Jacob and Laynie. When they consider moving back to LA, Jacob balks at the ghosts still haunting them there and blames the place: “LA crushed people who carried even an ounce of excess doubt….” Is their communal wanderlust spirit ever possible to satiate?

I think they’ll settle down in South Dakota for the long haul, and Laynie will be happier than Jacob because she doesn’t torture herself about the place the way he does. Jacob will always resent South Dakota for not welcoming him and his brother when they moved there as orphaned teenagers; one day he’ll be hopeful about belonging there, and the next he’ll be crestfallen about never belonging there. I don’t have a sequel planned or anything, but these characters still live in my imagination and I can see that about them.

Settling down doesn’t mean there’s no more wanderlust, and they’ll always have their “dreams of away.” This wanderlust isn’t fueled by a desire to be constantly on the move physically, but by a sense that they have to keep in motion to find a balance within themselves and between themselves. Where that motion happens doesn’t matter much. The Jacob and Laynie from the end of the novel, after they’ve put themselves through the wringer, could handle living in LA again because they’ve found the groove of their life together. They’ve reached a point of maturity and balance that will let them live anywhere. They understand that even though geography shapes them, their personal psychogeographies ultimately shape them much more.

The psychogeographies of characters is such lovely fuel in fiction. Is exile also a useful condition in storytelling?

Exile is an enormous force in my fiction, but I don’t think it is in everybody’s. There’s plenty of great fiction about belonging to a place and being part of a community—with the opportunities and obligations this brings—but that’s not a state of being I understand well. I typically write about people who are displaced by circumstance or simply choose not to settle, and I find them more interesting than “belongers,” because their relationship to their setting is varied and can change on a dime. They’re in constant interplay with their environment, always thinking about what places mean to them and what (if anything) they mean to those places.

That perspective is hard-wired into my personality and my family history. I’m an Ellis Island mutt whose family came to America with few resources around 1900, mostly from central Europe. Three of my four grandparents weren’t native English speakers, and my mom’s parents never became American citizens. My father’s side of the family often referred to her as “the Polack,” and I spoke bits of Polish every day until my grandfather died when I was five.

So deep in my psyche lives a sense that I don’t belong. It’s admittedly a continuous self-exile, and I’m drawn to that mentality more so than I am to the very real stories of physical exile and migration that are (with good reason) getting so much attention today.

What other authors traffic in exile that you admire?

The primary example of this approach to writing for me is Joseph Conrad—and I say this knowing that his reputation is taking a beating right now. On the surface he was a Pole who became an Englishman, but he was no “belonger.” He saw that we carry our internal dramas everywhere we go and unfold them like traveling amphitheaters, acting out our plays with whatever props and supporting cast we have at hand. Our physical geography will change how each drama plays out, but the fundamental things that make us individuals—the array of voices on our internal radio stations—keep playing wherever we go. And they aren’t a burden. They’re what gives us our beauty.