Editor’s Note: This is the first installment of Quotes & Notes, a monthly craft essay series by Steven Wingate. Each essay responds to a (famous or obscure) dictum on writing from a prominent fiction writer.

“You are not your characters, but your characters are you.”

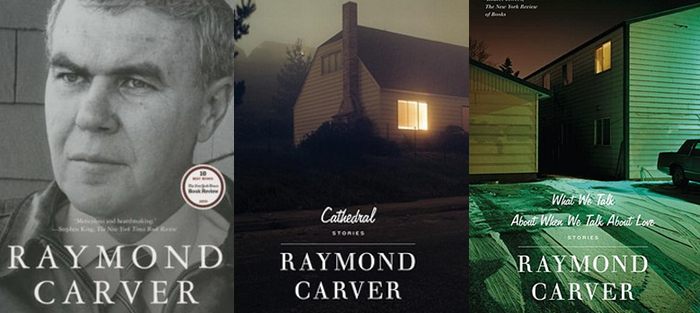

– Raymond Carver

Let’s face it: fiction writers do not have a reputation for being carefree, untroubled souls. Even our fellow artists consider us broody navel-gazers who are overly introspective and perhaps even in love with our own problems. (We do, after all, tend to keep writing about characters whose psychic profiles overlap significantly with ours.) The general public is hardly more charitable, usually assuming that (a) we study them to gather material, or (b) we all write thinly-veiled autobiography, and are so blind as to not even be aware of it.

Do we deserve assessments like these? Probably so. We spend a great deal of our time listening to (and talking back to) characters who do not exist, a behavior which might lead to incarceration if the grand tradition of fiction did not justify it. We create our personal bag of archetypal characters, many of whom resemble each other, and we often aren’t aware of their similarities until (a) we have worked with the characters for years, or (b) someone else brings those similarities to our attention.

When we write fiction, whether of a literary stripe or in the genres, we are bound to run up against the truth of Raymond Carver’s dictum. All of our characters—whether they arise from our imaginations, from real-life individuals, or from the conventions of a genre—are determined by the scope of what we ourselves are able to envision. We can move them to places we have never lived, in centuries yet unseen, and they will still be bound by the restrictions of our own emotionality. We can sail them down the Amazon in tuxedos if we wish, but our characters will always experience life through the lenses we make for them, seeing only those colors in the spectrum that we can see.

But seeing a color in a spectrum and discerning it with the mind are entirely different actions, which is why the relationship between our authorial psyches and our characters’ psyches is so unclear and rich. Our characters can see hues that we are not aware of seeing, and for this we should be grateful. It means that our character set is not limited by what we are, but by what we are capable of being—a vastly larger pool that leads to a richer experience for both writer and reader. But in order to get into this larger pool, we need to resist the temptation to embrace only the second half of Carver’s quote, simply accepting that our characters will always be us. This can be a dangerous and too-comforting fact when considered on its own, lulling us into a malaise that keeps us from working to make our characters unique and full-bodied.

But here the first half of Carver’s dictum—You are not your characters—puts the lie to any facile interpretations. If our characters are us but we are not them, there is a necessary gap between us and those we create on the page, and this gap is of supreme importance to the practice of fiction. Carver’s observation is not a free pass on the task of forging characters that are discrete from (though admittedly spawned by) the authorial self, but an invitation to throw ourselves into an author/character vortex that becomes less clear the longer we look at it, and that gives us more freedom the longer we cultivate its paradox.

In this vortex, each of our characters can see aspects of the spectrum that their authors can’t—at least not all the time. They embody what we might become, what we are afraid of becoming, what we have missed the chance to become, etc. It’s as if some aspect of ourselves has jumped into a petri dish and become a full human being with its own wants, confusions, and contradictions. By exploring these characters on the page, we naturally learn more about the world and about ourselves through their eyes. It might be as simple as learning a certain cuisine because we want to know how a character cooks it, or as complex as discovering how our childhood fears have influenced our choice of adult friends. I suspect and hope that all fiction writers have experienced this, and I don’t believe it’s trivial. The time we spend alone and in silence naturally leads us to grope toward self-understanding, and that groping itself is what pulled many of us into writing to begin with.

The specter of self-understanding is always there, underneath the surface of what we do, and we should feel free to recognize its imprints on our lives and work when we see it. Recently, when looking at some old (mostly unpublished) fiction, I noticed several male characters who either work with wood or have fathers who do. I know that this isn’t just me bleeding into my characters because my father could barely pick up a saw without swearing, and I myself exult over simply cutting a 2 x 4 straight. But this recurring character has, through iteration and time, moved out of my imagination and into my consciousness. What these woodworking characters are trying to tell me, I don’t know and can’t know, but chances are that I won’t come up with any new ones. They aren’t coming out of the vortex anymore, and any not already “alive” would feel like stock characters. I am sad about this, but must accept that their rising from my imagination to my mind is part of the fiction process—a necessary by-product of the interaction between me and the characters who carry my psychic DNA.

For years I was deeply ashamed of moments of realization like this. I tried to bury them, as if what was once hidden needed to remain so forever in order for me to create. (By the same logic, some writers won’t undergo psychoanalysis or counseling for fear of destroying their creativity.) But lately I’ve been seeing it differently. When the worm of the self burrows into the muddle of our lives, it sometimes digs its way back to the surface again and bring hidden things to light. When that happens we can either (a) lament that we have lost a rich source of characters, or (b) acknowledge that the worm is set loose again to find new characters to burrow through. In this way we can have our cake and eat it too: we can be in love with our problems (as we are often accused of) and yet not have to stay in love with the same problems forever.

Of course it isn’t that simplistic. But if we approach the practice of fiction sincerely, we can’t stop these self-understandings from happening any more than we can try to manufacture them. Consciously engaging in this burrowing process will invite us to regurgitate our problems onto the page, which always yields dreck. When such moments arise, however, we should see the opportunities that they offer: refreshment of the imagination, new territory to plow, and perhaps even a reconnection with what brought us to fiction in the first place. Trusting the mind and imagination to work in concert as we explore the author/character vortex is no grave sin—provided that we let both mind and imagination do their jobs in peace—and it can keep us from repeating ourselves in ways that sap our energy. The question remains whether all this vortexing, burrowing, and self-understanding can ever amount to anything in a writer’s life.

But this is another issue entirely, one I would like to explore in the second half of this essay by launching from the words of Gustave Flaubert: “Do not imagine you can exorcise what oppresses you in life by giving vent to it in art.”

Further Resources

– Via carversite, explore a choice selection of Raymond Carver quotations.

– The first of these two interviews with Carver touches on the question of autobiographical elements in his own work.

– In this (London) Times Online piece, Melvyn Bragg (author of Remember Me) asks: “Why not step inside yourself [when writing fiction]?”