Introduction:

Sometimes the muse assumes the unlikeliest forms. When composer Eric Moe began searching for a lyrical inspiration for a new piece, a collection of Hideous Men might have seemed an odd place for lightning to strike. But in the chopped-up, pseudo-classical, post-modern melange of David Foster Wallace’s “Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko” he found both personal connection and musical possibility. The resulting piece debuted in 2005, and enjoyed a New York revival earlier this year. Here Moe describes his long, strange journey. The interlude quotations come from Wallace’s original short story.

Or like stout Cortez, when with eagle eyes He stared at the Pacific—and all his men Look’d at each other with a wild surmise— Silent, upon a peak in Darien. —John Keats, “On first looking into Chapman’s Homer”

A whole new kind of ritual narrative, neither Old Comic nor New Tragic – the sit-trag.

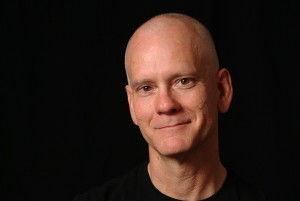

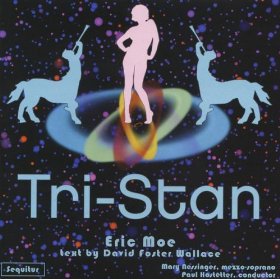

This spring I had the good fortune to have a New York revival of my one-woman opera/situation-tragedy Tri-Stan, a musical setting of David Foster Wallace’s story “Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko.” Also this spring, I had the spectacular good fortune to be awarded a residency fellowship as a composer at the Camargo Foundation in the south of France. The excellent writers in residence at Camargo were very much interested in how a composer collaborates with a writer and deals with setting a text to music. After all, how any composer works with writers and their words is shrouded in mystery to anyone but the composers themselves. (In fact, everything a composer of contemporary art music/concert music does is a well-kept secret in America). But the writers were interested not only in this process in general, but also regarding this particular writer and this particular text. After all, DFW’s work is not exactly simple, not to mention everyone’s fascination at the idea of collaborating with a literary icon.

This spring I had the good fortune to have a New York revival of my one-woman opera/situation-tragedy Tri-Stan, a musical setting of David Foster Wallace’s story “Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko.” Also this spring, I had the spectacular good fortune to be awarded a residency fellowship as a composer at the Camargo Foundation in the south of France. The excellent writers in residence at Camargo were very much interested in how a composer collaborates with a writer and deals with setting a text to music. After all, how any composer works with writers and their words is shrouded in mystery to anyone but the composers themselves. (In fact, everything a composer of contemporary art music/concert music does is a well-kept secret in America). But the writers were interested not only in this process in general, but also regarding this particular writer and this particular text. After all, DFW’s work is not exactly simple, not to mention everyone’s fascination at the idea of collaborating with a literary icon.

[Before going any further, it’s a fair question to ask what a musical setting of a literary text offers. I mean, from the composer’s point of view, why bother? Thousands of songs, operas, and whatnot, many of them well-loved and some of them masterpieces even, have texts that can only charitably be described as mediocre. And getting permission to set a published text under copyright—even if the author is enthusiastically in favor—can be excruciatingly difficult, as contemporary publishers seem incapable of drawing a distinction between an individual concert music composer and, say, Disney. For my part, if I’m going to be spending serious time scrutinizing the structure, syntax, phonemes, and, yes, even the meaning of a text, I want to work with something that’s going to be truly rewarding.]

Our discussion at Camargo continued: What’s in it for the writer? A Shakespeare sonnet, for instance, is complex enough without adding a layer of musical structure. I suggested this extra layer would be an asset in my lapidary soliciting abstract to DFW. I explained: “…musical setting can expand, even further, the range of allusions, make the C#-minor aria audible, and in general add another dimension to the (admittedly already incredibly rich) piece.” But music can also focus, heighten, and unify and thus can offer an inviting way into a text, roll out a red carpet by giving the listener a persuasive interpretation, like a masterful actor.

Plus it can sneak a firecracker of smartass irony in with a beautiful tune.

…the dark logic of a genuine entertainment-market inspiration.

I’ve heard that writers often struggle with structure. So do composers. If you want to see some serious structure-struggle, try writing a large-scale piece of music. But composers do have one advantage writers don’t: we can use their texts as a skeleton, or at least scaffolding. I did this in two earlier big vocal pieces, Sonnets to Orpheus and Siren Songs. Both of these resemble the classical song cycle, a genre invented by Beethoven, I believe. Sonnets to Orpheus was a setting of eight of Rilke’s fifty-odd sonnetsin Stephen Mitchell’s translation, a selection that preserved the narrative arc of the Orpheus story. Siren Songs took an opposite tack, setting six siren-related texts from all over the geographical and temporal map: Alexander Pope’s eighteenth-century translation of Homer (eighth century BCE); my own contemporary translations of Dante (early fourteenth) and Kafka (early twentieth); an explorer’s chronicle (early seventeenth century); and two freshly written works by living American poets, Janet McAdams and Paula McLain.

For the next big piece, I wanted to try something different still. Mary Nessinger, an amazing singer living in New York who could sing anything I could dream up and a lot of things I couldn’t, commissioned me to write a dramatic concert piece for her. After my previous globe-hopping and time-traveling, I was curious to see if I could write a distinctly American piece, a national epic for my generation of ironists, who want nothing more than, as DFW puts it, to “put a happy-face mask on a nation’s terrible shamefaced hunger & need.” A Ring of the Brady Bunch, a Fanfare for the Pop Ironist. Not an easy task, since our national sagas are all computer-generated-imagery fests with recycled plots and our folk music consists of TV-sitcom theme songs and advertising jingles.

…at this point Ovid the O. got the idea to turn the entire affair into this sort of ironically contemporary & self-conscious but still mythically resonant & highly lyrical entertainment-property, a ‘…high-concept miscegenation-of-Romantic-archetypes-type metamyth,’ a kind of hottub-swingers’ incest among Tristan & Narcissus & Echo & Isolde

I was looking for a text that might be suitable for a musical setting. I had already read many, many collections of poetry, short stories, flash fiction, and one-act plays. But I’d been having a lot of trouble. Finding the right text is a tricky business. First, there are practical considerations. It has to be short; singing words generally takes a lot longer than speaking them, which in turn takes a lot longer than reading them. Plus it’s helpful if the words are short but with lots of long vowel sounds, and arranged in short sentences. (Long vowels allow a singer to hold a note easily without causing listeners to scratch their heads). Rhyme is also a plus, because it’s hard to understand sung speech. Everyone has their favorite mondegreens—imperfectly perceived lyrics. A classic example from Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”: “Excuse me while I [pick one] (1) kiss this guy or (2) kiss the sky.” Professional lyricists specialize in making texts that retain their intelligibility when sung. I didn’t want to write a Broadway musical, though, and I wanted literary quality. I also wanted something profound and funny.

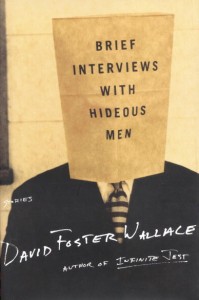

Then I began reading David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It was in the middle of a story called “Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko” that I slowly began to realize that this was what I had been looking for. I’m not sure exactly where or what triggered it. Was it the passage where the demiurge Erythema appears to the suffering Reggie Ecko, victim of a massive self-esteem displacement, in the mortal guise of Robert Vaughn hosting Hair Loss Update? (I reluctantly admit that I actually do remember this late-night infomercial from UHF TV). Yet there was more to it than nostalgia. For example: “… it was just one of those large-r Romantic love-at-initial-reception things, the stuff of chivalric myth, the Tristian/Lancelotian fuck-it-all plunge, the Sicilian thunderbolt, the Wagnerian Liebestod.” I was also struck by DFW’s empathy for his all-too-mortal and all-too-fallible fame-seeking or substance-abusing characters. Postmodernism with a heart.

Then I began reading David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It was in the middle of a story called “Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko” that I slowly began to realize that this was what I had been looking for. I’m not sure exactly where or what triggered it. Was it the passage where the demiurge Erythema appears to the suffering Reggie Ecko, victim of a massive self-esteem displacement, in the mortal guise of Robert Vaughn hosting Hair Loss Update? (I reluctantly admit that I actually do remember this late-night infomercial from UHF TV). Yet there was more to it than nostalgia. For example: “… it was just one of those large-r Romantic love-at-initial-reception things, the stuff of chivalric myth, the Tristian/Lancelotian fuck-it-all plunge, the Sicilian thunderbolt, the Wagnerian Liebestod.” I was also struck by DFW’s empathy for his all-too-mortal and all-too-fallible fame-seeking or substance-abusing characters. Postmodernism with a heart.

The sense of recognition became stronger when I read some of DFW’s essays and discovered that we were about the same age, that he, too, had grown up in downstate Illinois in an academic family, and that he had played a lot of tennis on summer days hot enough to melt asphalt. We had both spent serious time at the Illinois State Fair, sampling corn dogs and viewing the world’s largest hog. Reading Infinite Jest, I discovered that we also shared an interest in addiction issues and popular culture, a fantasy of creating complexly addictive artworks, and a fascination with the troubling nature of competition and celebrity.

…myth, classic & Classical myth: rich, ambiguous, archetypal, cosmological, polyvalent, susceptible of neverending renewal, ever fresh

True, the story was on the long side. And the sentences were long and complex, containing long and complex words. (The first less-than-scrutable sentence begins with the phrase “The fuzzy Hensonian epiclete Ovid the Obtuse…” and rolls on for thirty or forty more words. “Hensonian” refers – I’m pretty sure – to Jim Henson, the muppetteer; you won’t find “epiclete” in the unabridged OED). Words like “thanataphiliacal” and “mithradititic” pose challenges for musical text setting. So much for the practical side of things. I would just have to find some extraordinary solutions. Making art is a lot more exciting when big risks are being taken.

But I was most excited by the subject matter and its treatment, to see how the text dealt self-referentially with myth, the common stuff of high and low art, of grand opera and Hollywood. Add the timely and timeless themes of obsession and addiction, self-image and self-regard, and late ‘70s TV sit-coms – neither timely nor timeless, but definitely fascinating – and it had me.

…in a nation whose great informing myth is that it has no great informing myth, familiarity equaled timelessness, omniscience, immortality, a spark of the vicarious Divine.

The first words of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, one of the first operas ever,are “Io la Musica son,” or “I am Music.” From the start, operas often did not make a distinction between words and music, since words exist, sonically, in the domain of music. Tuneful parts are often segregated from wordier parts, however. In Schönberg’s Moses und Aron, the seductive Aaron sings his lines, while the stammerer Moses speaks.

For Tri-Stan, I decided to use both rhythmic speech and song. Sometimes the use of song is predictable. In the big dreamsong aria, for instance, a vision sent by the goddess Codependae who appears in the dream disguised as a singing three-headed siren (the three heads belonging to the three CEOs of Tri-Stan, each named Stanley). The words needed to be visible as well as audible, both to highlight the text’s literary quality and to aid the assimilation of the baroque complexities of the language. Supertitles in opera productions are now commonplace, but I wanted Ultra-Titles®, wherein the very presentation of the text itself would be artistic. To my delight, I was able to persuade the brilliant video artist Suzie Silver to make a video incorporating the text, which now accompanies live performances of the work, synced by Suzie in real time to the music through various high-tech means.

But there was nothing high-tech about my collaborative relationship with DFW, which was an old-fashioned correspondence. The printed word, via the USPS. A certain delay and distance was built into the arrangement that felt odd in the age of instant communiqués. It didn’t involve sound, aside from the CDs he asked me to send him; my proposal/fan letter and his cheerful agreement kicked off a literary friendship. I was disappointed that I didn’t have closer contact with him—an email address at least—but I was also relieved. I needed to perform some surgery on the text to fashion it into something I could use, and I was glad to have a trusting, hands-off writer to deal with. I was clear on the need to abbreviate the story, and on the strength of a vague promise “to cut as little as possible,” he mercifully allowed me free rein.

Alas, we no longer get to say “alas” with a straight face…

We had only one point of divergence. The Guggenheim Museum was interested in presenting the work on its Works & Process series (the NYC premiere of the Sonnets took place in this series). Works & Process is all about collaboration, and so DFW’s presence was necessary. At this point I found out how phobic he was to public appearances. I’m grateful to Jonathan Franzen, a close friend of DFW’s, for eventually explaining the situation to me. I had trouble understanding it at the time. Music is a performing art and thus ultimately a collaborative venture, even if it requires a vast amount of solitary preparation. Every performer has felt the hot breath of the composer on the back of their neck. And a public audience is generally involved as well. There are plenty of shy composers (myself included), but not many reclusive ones. I wrote the piece in the mountain solitudes of Montana, but I wrote it for New York City musicians – and a New York City audience – to bring to life. Luckily, an alternate and excellent venue was soon found that didn’t require the writer’s presence: Merkin Concert Hall near Lincoln Center.

Long-jaded viewers were rapt, Vanna’s show stolen, critics indulgent, & sponsors all but manic.

So even in the writer’s absence, the piece had great success. Mary Nessinger dazzled, effortlessly switching from Valley Girl-ese to mock-Puccini to pseudo-Wagner to bizarre hip-hop; Paul Hostetter, the conductor, carved out a sizzling interpretation of the piece with great performances from the Sequitur musicians, an orchestra of new music superstars. The audiences loved it. So did the critics, who gave it close-to-rave reviews in the New York Times and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. The piece was a hit, as much as anything in the culturally marginalized world of contemporary classical art music can reasonably hope to be.

But one more test was to come.

I packed up a copy of the fresh-pressed commercial CD recording plus a DVD dub of the video and mailed it off to DFW. I wondered. Time passed. I wondered. I stopped wondering. Then one day I got a card in the mail from him with a funny and warm appreciation. I was greatly relieved and very, very pleased. He was my target audience, after all. There was talk of a special performance of the piece at Pomona College, where DFW was on the faculty and where the story is set, the fluorescent basin of [post-] medieval CA itself.

It’s right around here that Ovid the O. tone-shifts to Lament.

Like so many others, I read the news flash of his death over and over. I was bereft. I went to the gym to distract myself, and, in an eerily Tri-Stanian moment, heard the news again there on TV. A lot of friends and even people I don’t know so well contacted me to express sympathy. A few trawled for inside information or gossip. I was way too sad to say much by way of thanks for the condolences, and I was way too sad to work up much indignation about the voyeurs. I was touched when one friend, a composer, told me he was listening to Tri-Stan as his personal memorial service for Wallace.

When someone I know dies, I find myself thinking about the last communication I had with them, to see if I can draw any comfort from it. This can be painful. I once was very late in answering an extraordinarily nice letter I’d received from a composer whose music I’d programmed. I got my letter back, unopened, with a terse note from the grieving spouse: “Lou died last month.” With DFW, at least, I could skip the self-reproach. I even allow myself, from time to time, a consoling fantasy. More than a few times, I’ve had the exhilaration of hearing a performer give a truly revelatory performance of a composition of mine. And I hoped that my musical setting might have made DFW feel this same sort of exhilaration.

In the last pages of “Tri-Stan,” Sissee Nar sees herself fatally reflected in mirrored sunglasses, and she is “…transfixed & shocked by an image which actually she alone in all the fluorescent basin saw in truth as imperfect nay flawed & inadequately Enhanced & like totally gnarlyly mortal.” In contrast, I like to think I might have given DFW a mirror to see one facet of the beauty and depth of his own story. I like to imagine his pleasant surprised smile, a mirror of my own wild Keatsian surmise upon reading “Tri-Stan” for the first time.

Further Links & Resources

- Visit Eric Moe’s website – ericmoe.net – for more about his work and compositions, visit Suzie Silver’s site – harpsilver.com – for videos from Tri-Stan and stills from her Ultra-Titles® for the opera.

- Read the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette review of Eric Moe’s Tri-Stan here.

- Read contributor Scott F. Parker’s essay / homage to David Foster Wallace, “The Real Question” (FWR, 1/7/2010). In it Parker describes the powerful impact of Wallace’s story “Good Old Neon” and the fragile, mysterious connection between writer and reader.

- A New York Times mention of a brand new staging of Moe’s “miniature monodrama” titled, “Jozaphine Freedom,” by the ensemble Sequitor.

- Interested in questions of translation? Jennifer Solheim unearths the inspiration required to convert one art form to another, in her essay, “The Seamless Skin: Translation’s Halting Flow.”