Editor’s note: A version of this essay appeared earlier in Dutch in the Belgian literary magazine Deus Ex Machina (translation by the author).

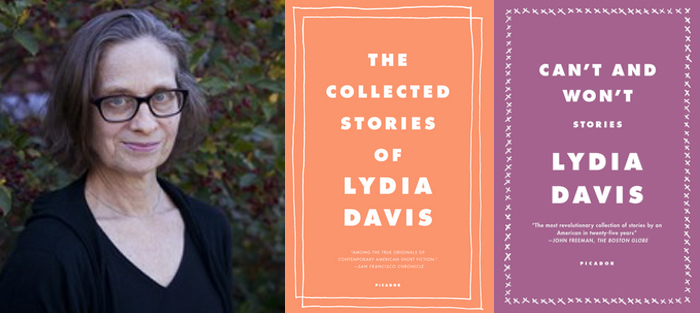

“I write from my own interest. If something interests me, whether it’s a piece of language or a family relationship or a cow, then I write about it. I never judge ahead of time. I never ask, Is this worth writing about?” —Lydia Davis, The Paris Review (2015)

No matter how unspectacular the goings-on, Lydia Davis is happy to write about bovines and relatives, as we learn from an interview conducted by Andrea Aguilar and Johanne Froth-Nygren for The Paris Review. Davis will write about what interests her. A simple enough statement, but it has the tone of confession. She’s basically saying she refuses to worry about the tellability of her stories.

I’ll admit I’m not much inclined to question her sincerity. Both as an author and a translator, Davis is a champion of accurate word choice, and I have a tendency to confuse precision with truthfulness. But open her Collected Stories at random and you’re likely to find confirmation. You might come across a story about practicing the piano, for instance (“The Way to Perfection”), or about spelling (“Nietszsche”). You might read about having to hurry through a museum (“20 Sculptures in One Hour”). “Absentminded” is about letting a cat in, but not just that. It’s also about feeding the cat. More, it’s about the thoughts that keep interrupting you while you let the cat in and feed it. Which, granted, still doesn’t amount to the kind of story that’ll keep barflies awake in the wee hours.

Three writers walk into a bar…

There’s No Story There

Tellability is what gives stories a right to exist. It’s the reason they’re allowed to be told. The reason they can use up time and space, energy and oxygen. Tellability is the magic spell that turns an ordinary occurrence into this thing with vastly more meaning, a story.

Sociolinguist William Labov began looking into tellability in the early 1970s. He wanted to know what becomes worthwhile telling in everyday conversation. Afterwards, narratologists got to work with the concept. They applied it to the study of stories in general, and of literary stories in particular. They wondered what gains tellability in narrative prose, and looked for answers, first, on the level of content. Their conclusion was usually a variation of: “Tellable is what disrupts a pattern of expectation.” Labov already noted that some “violation of an expected role of behavior” had to occur if an incident was to become a story. Second, they went looking for answers on the level of form. They considered the ways in which stories are told, focusing, among other things, on the order of events and the style of narration.

I’m interested in tellability because Davis seems to have so very little of it. Many of her stories are about the most banal facts of life. Counterintuitive as it may sound, narrative prose actually has a privileged relationship with such facts. Ordinary events are a vital part of narrative literature as we know it nowadays. In The Rise of the Novel (1957), Ian Watt describes “the novel’s closeness to the texture of daily experience,” the ease with which it includes the trivialities of life. According to Watt, before the eighteenth century, when the novel became more or less what we know today, “much of man’s life had tended to be almost unavailable to literary representation, merely as a result of its slowness.”

I’m interested in tellability because Davis seems to have so very little of it. Many of her stories are about the most banal facts of life. Counterintuitive as it may sound, narrative prose actually has a privileged relationship with such facts. Ordinary events are a vital part of narrative literature as we know it nowadays. In The Rise of the Novel (1957), Ian Watt describes “the novel’s closeness to the texture of daily experience,” the ease with which it includes the trivialities of life. According to Watt, before the eighteenth century, when the novel became more or less what we know today, “much of man’s life had tended to be almost unavailable to literary representation, merely as a result of its slowness.”

“Almost but not entirely,” might have been Mikhail Bakhtin’s reaction. The Russian philosopher and literary scholar argues that instances of “everyday time” and of random day-to-day life can be found as far back as Antiquity. Yet he agrees with Watt that they become particularly insistent and widespread in modern narrative prose.

Ironically, the everyday is just as easily lost. Narrative prose and the everyday have that special bond, but it’s of the love-hate kind. Watt points out that while in “earlier narratives” coherence was based mainly on “disguises and coincidence,” the novel needs “a causal connection operating through time.” A novel is coherent if readers can make this causal connection, if they can explain what happens logically by going back to what came before, taking into account the biography and context of characters. The novel differs from older forms of narrative literature “by its use of past experience as the cause of present action.” But, as Michael Sayeau explains in Against the Event (2013), this is not without consequences for those everyday scenes that are identified as causes.

This causal logic retroactively translates uneventful daily experience into the causal grounds of “present action,” and in doing so establishes a structure that permits the ordinary or uneventful entry into the form, but only under the condition that it is structurally determined as the subsidiary backdrop against which significant, revelatory action can occur.

The irony of the novel, in other words, is that it brings everydayness into literature only to cancel it out again. As soon as trivial events are identified as precursors of more important ones, they’re not so trivial anymore. The novel “translates” day-to-day experience “away from the very contingency and ordinariness to which [it] seems to offer representational space,” Sayeau writes. It has to, or there would be no story. You’d stop turning those pages. Tellability vs. the everyday: 1-0.

Three random writers walk into a random bar…

The Promise of Micro-Fiction

In a 2005 interview with Michael Haneke, film critic and journalist Serge Toubiana asks the Austrian filmmaker about his Seventh Continent, in which a family of three commits suicide. To the urgent question of why, various media – the film is based on a true story – had formulated the obvious answers: the couple was in debt, their relationship was in crisis. The Seventh Continent was Haneke’s attempt not to give such easy answers. He wanted, in fact, to give no answers at all. He slaved on the screenplay for six weeks and got nowhere. The problem, he came to realize, was causality. Whatever he wrote into the story before the suicide seemed to be the reason for it. It made the task he’d set for himself impossible. He’d wanted to honor the inexplicable nature of this family’s extreme act. He’d wanted to depict their lives the way they were, which is the way all our lives are – both entirely plain and infinitely complex. He was doing neither.

His predicament was the same as the novelist’s. The everyday gets caught in a web of causal connections – and dies. Haneke tried to solve the problem by tearing apart the web. He imposed a strict protocol. From the life of this family he would select three days that were exactly one year apart. Last in line would be the day of the suicide. Each of the three sections would begin with an intertitle that shows what year we’re in. The idea is to make it look like three arbitrary moments in time. It’s randomness as a selection criterion and a structural principle. He also uses it for 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance. One of the seventy-one fragments is a mass murder in a bank. How it results from the banal sequences preceding it remains unclear. It’s a chronology, nothing more. Of chance, at that. Rather than answer questions of causality, Haneke wants to highlight the messy and often arbitrary nature of events.

His predicament was the same as the novelist’s. The everyday gets caught in a web of causal connections – and dies. Haneke tried to solve the problem by tearing apart the web. He imposed a strict protocol. From the life of this family he would select three days that were exactly one year apart. Last in line would be the day of the suicide. Each of the three sections would begin with an intertitle that shows what year we’re in. The idea is to make it look like three arbitrary moments in time. It’s randomness as a selection criterion and a structural principle. He also uses it for 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance. One of the seventy-one fragments is a mass murder in a bank. How it results from the banal sequences preceding it remains unclear. It’s a chronology, nothing more. Of chance, at that. Rather than answer questions of causality, Haneke wants to highlight the messy and often arbitrary nature of events.

Whether he has effectively remedied the problem of causality is not so much at issue here. I’m more interested in what this means for micro-fiction, or flash fiction, or whatever you choose to call the stories that seem shorter than short. Because the brevity of the form now seems to hold a promise. In a micro-story, causal connections don’t need to reach very far. The story can present an ordinary event not as the run-up to a more decisive moment, but as the thing itself, with the texture of day-do-day experience intact. And this without testing readers’ patience. Depending on who’s breaking it down, this is a great weakness or a great strength of micro-fiction. Personally, I’m appreciative of a win-win situation. It’s like a white lotus: beautifully symmetrical, and you almost never find one. Micro-stories make it possible to prioritize the everyday over the tellable without having to compromise the reader’s pleasure. Win-win.

This is not what most theories of the genre emphasize, though. Most emphasize tellability, especially when it comes to English-language micro-fiction. In “Microfiction,” an oft-quoted article from 2012, William Nelles writes that in very short stories the action is typically “more palpable and extreme” than in longer ones.

[O]ne might, of course, write microstories in which nothing significant happens, but as far as I can tell, no one does, probably because stories in which “nothing” happens depend so strongly upon our intimate knowledge of, and emotional investment in, that particular character to whom that particular nothing happens.

He speaks in the general terms of genre, but many of the stories Nelles discusses are written in English. He’s not wrong in that context. Much of the micro-fiction that is so frequently anthologized in the US and the UK nowadays fits his description. It tells realistic stories, and it tells them well. They’re emotionally gripping and crisply dramatic and capture crucial moments in people’s lives. The fabulous wikiHow is on the same track. Here’s “How to Write Flash Fiction,” according to the website: “Begin your story at a moment of change; a crucial moment to the narrative.” And, “Your flash-fiction piece should arrive at its main narrative or plot conflict in the first paragraph—or even the first sentence.” Right. Got it.

Three random writers walk –

Micro-Fugue

Not very flashy, by comparison, are Davis’s stories. Their level of tellability is deplorably low. Davis herself blames the everyday. She likes to create characters who simply “focus on one thing at a time,” she tells Sarah Manguso in The Believer (2008), “as we tend to do in life.” Tranche de vie. Meet the cockroaches who engage in expected cockroach behavior in this ordinary house, for instance (“Cockroaches in Autumn”). Enter the universe of a woman who prepares fish at the end of the day (“The Fish”). You might notice she’s a bit tired.

Some of Davis’s stories do contain more drastic events, but these tend to be told in strangely undramatic ways. According to Manguso, Davis’s protagonists are prone to observations that “might be described as dispassionate – sometimes humorously so – and for this reason the considerable emotional component of Davis’s stories is often subtextual.” Even dramatically charged situations don’t seem particularly eventful in this kind of flash fiction. The intensity of emotion is left out. The drama is missing.

Some of Davis’s stories do contain more drastic events, but these tend to be told in strangely undramatic ways. According to Manguso, Davis’s protagonists are prone to observations that “might be described as dispassionate – sometimes humorously so – and for this reason the considerable emotional component of Davis’s stories is often subtextual.” Even dramatically charged situations don’t seem particularly eventful in this kind of flash fiction. The intensity of emotion is left out. The drama is missing.

This is how Davis portrays a serious relationship crisis (“City People”): “The country is nice enough […] but they are uneasy. They quarrel more often. They cry, or she cries and he bows his head. He is pale all the time now.” Here’s a daughter describing events that can only be traumatizing (“How Difficult”): “For years my mother said I was selfish, careless, irresponsible, etc. She was often annoyed. If I argued, she held her hands over her ears.” I picture the mother who does this. Who, like a big child, covers her ears whenever her daughter tries to say something. That’s pretty extreme. But that’s not how it’s told.

Davis translated the French writer Maurice Blanchot and feels kinship, she says, with his “going deeply into a small, mysterious moment” in such a way that “he didn’t need a dramatic story line.” Asked about her music education and how it influenced her writing, she replies, in The Paris Review:

[O]ne of my favorite composers was always Bach, and he still is. Think of the fugues. Here you have a highly cerebral structure, something almost mathematical. And yet it’s very emotional at the same time. So within that very mathematical and very disciplined structure, you have this huge emotional impact.

In the fugue, polyphony and variation are curbed by a fixed structure and patterns of repetition. The turmoil is there, but it’s subdued. The same can be said of the micro-stories in which Davis does write about more drastic events. Emotions are at their core. They’re stories of passion and suffering. They talk of desire that devastates, the horror show of fear. Below the surface all surges and rages. But to the naked eye the sea is calm.

Three random writers walk into a random bar. They are apparently without emotion…

Everyday Wonder

An interesting observation is that I’m not bored to tears reading about people feeding theirs cats and cooking fish on a weeknight. Why is that? How is Davis turning the most ordinary vignettes into such tellable stories while still preserving the fabric of the everyday? How is she carrying out this promise of micro-fiction?

Part of the answer is undoubtedly that hinting at an emotion can be more powerful than endlessly belaboring it. This is what Michael Haneke took away from Robert Bresson’s Au hazard Balthazar. The lead for this French film from 1966 goes to… a donkey. The animal’s not acting. It’s not trying to express any emotion, but it does so anyway. It plays a convincing and endearing Balthazar. In “Terror and Utopia of Form,” an essay about the film, Haneke writes that it had always “struck [him] as obscene to watch an actor portray, with dramatic fury, someone suffering or dying,” because “it robbed the viewers of […] their most precious possession as viewers: their imagination.” Emotions can hit you harder if you have to imagine them yourself. Isabelle Huppert by the window in Haneke’s Amour. A desperate daughter in an impossible situation. But we see her from the back only. At a distance. There’s no music. There’s hardly a sound. Her posture betrays something.

Another part of the answer is humor. I gladly keep reading if a good joke is in the cards. Fact. (Three random –)

But there’s something else still. Something special. For want of a better term, I’ll call it everyday wonder. So many of Davis’s micro-stories are steeped in it. And, again, I want to know how exactly she does this. The first thing to note is her style. The portion of literal language, for one. How few metaphors and similes she uses, and how close the ones she does use stay to the fictional world. In her stories, the sound of the ocean is “enough of a silence” for a mother and her son to sleep peacefully, and a woman’s eyes glow “with satiety, as though she has eaten a large meal.” A space is “like stone […] because of the coolness of it and the gray shadow.” Pain is “hard and cold, like a bar of metal.”

None of this imagery is particularly far-fetched or surprises the reader by bringing in a completely different universe. Davis also tends to opt for simple words. A sample of literal and sober language from “City People”:

She wakes in a panic at night, hearing him sniffle. She wakes in a panic again, hearing a car go up the driveway. In the morning there is sunlight on their faces but mice are chattering in the walls. He hates the mice. The pump breaks. They replace the pump. They poison the mice. Their neighbor’s dog barks. It barks and barks. She could poison the dog.

This is the “pared-down style” Davis appreciates in Beckett, and of which she says, in The Believer: “I don’t believe, in the end, that there is any such thing as no style. Even a very neutral, plain style, one that doesn’t use colloquialisms, lyrical flourishes, heavy supplies of metaphor, etc., is a style.”

Davis is also very good at pointing out what everyone already knows. In “Our Trip”:

My mother asks on the phone how our drive home was, and I say “Fine,” which is not the truth but a fiction. You can’t tell everyone the truth all the time, and you certainly can’t tell anyone the whole truth, ever, because it would take too long.

“Not the truth but a fiction.” “Because it would take too long.” The reader is forgiven who, after such insights, retires to a darkened room in order to process for the rest of the day. It’s thrilling how reckless Davis’s narrators are with perfectly redundant information. They’re masters of stating the obvious.

And one last thing: “They have moved to the country. The country is nice enough […].” This is “City People” again. Further down: “The pump breaks. They replace the pump.” Another example, from “How Difficult,” where a mother, as mentioned, is of the opinion that her daughter is “selfish, careless, irresponsible, etc.,” after which the story continues:

She did what she could to change me but for years I did not change, or if I changed, I could not be sure I had, because a moment never came when my mother said, “You are no longer selfish, careless, irresponsible, etc.”

“Vary thy vocabulary” is an imperative you’re likely to find in every style guide (minus Shakespearean possessive perhaps), and rightly so. But fiction is a different thing. A narrator’s voice has its own laws to obey. And the stubbornness with which Davis’s narrators refuse to vary their vocabulary is highly effective.

Effective how? What is the result of this style? The literal and simple language, the fondness for stating the obvious, the lack of variation in wording – all conspire to create a specific gaze onto the world. A gaze that is childlike. The world and its happenings are approached with a degree of innocence. A sense of wonder emerges, also with regard to the everyday. Especially with regard to the everyday. Any adult can marvel at the seven wonders of the world, but it takes a child to appreciate the miracle of an average Tuesday. Either that or the collected stories of you-know-who.

Three random writers walk into a random bar. They are apparently without emotion. One begins to investigate the doorknobs. Another takes an interest in the bottom of her glass. A third in the soft middle part of her palate…

Lydia Davis Is Phenomenal

She is. I can say it and still maintain a semblance of credibility provided I use the word in its philosophical sense.

Phenomenology starts from the idea that it’s no use talking about the world in itself, as an external and objective entity. The reasoning is that we don’t have access to this world anyway. It needs to pass through the gates of our consciousness and senses first, and transforms in the process. Subjective experience is all we know. So phenomenology proposes to shift the focus, away from objective situations in the outside world and towards so-called “phenomena,” those same situations as they are actually experienced, colored by perception.

Davis frequently operates as kind of phenomenologist. In her fiction, we get access to the outside world only if it’s part of someone’s inner world. The filter of perception is always there. This is, I think, the final ingredient to complete the recipe for everyday wonder in the style of Davis. According to Ben Marcus in The New York Review of Books (2010), Davis’s work combines “a nearly autistic failure to acknowledge the emotional heart of the matter” with “a curious lack of interest in narrative scenes between characters.” Asked about this by Manguso, the author concedes: “I’m shying away from a certain artificiality that I perceive to be present in many such scenes as written.” What artificiality? Where does it come from? Her explanation is illuminating:

We all have an ongoing narrative inside our heads, the narrative that is spoken aloud if a friend asks a question. That narrative feels deeply natural to me. We also hang on to scraps of dialogue. Our memories don’t usually serve us up whole scenes complete with dialogue. So I suppose I’m saying that I like to work from what a character is likely to remember, from a more interior place.

It would feel artificial to Davis to portray an objective, external world, complete with ready-made dialogue. The stance is phenomenological: that’s not how the world enters consciousness. It’s not how we experience things, or how we remember the things we go on to tell. To Davis as a storyteller, only the realm of phenomena feels natural, the world from the inside out.

The End of the Story (1995) is a testament to this. Davis was reluctant to partition the novel into chapters because that would break “the illusion that you got inside someone’s head and they’re just thinking on and on.” It’s probably no coincidence that her only novel is not just about a love affair, but also about the impossible task of writing that novel, at least in any coherent way. All along we see the novelist-narrator call her own choices into question. Doubt seeps in from the beginning. She arranges the material one way, changes her mind, arranges it another way, changes her mind again – and ultimately exposes the arbitrary and deceptive nature of any arrangement. Subtext: “Because in actual experience, love relationships are anything but coherent stories.” Instead, they’re a succession of haphazard situations, unintended outcomes, attempts both fruitful and failed. They’re a big pile of loose ends, and don’t we all know it.

The End of the Story is a fitting title. This is a story that cannot end in any objective world. It can only end inside the protagonist’s own head, as something phenomenal. While she’s sipping bitter tea in a bookshop, she abruptly decides – spoiler alert – that this is it. The official end of her love affair. It’s a random decision that in one go ends the novel too: “since all along there had been too many ends to the story, and since they did not end anything, but only continued something, something not formed into any story, I needed an act of ceremony to end the story.” As David Winters points out in his 2014 essay “Like Sugar Dissolving,” “the narrator selects the scene almost arbitrarily, purely to put an end to something endless.” Yes. Even without the “almost.” The title already suggests it. The novel ends not with a conclusion but simply with a stop. Events and narration come to a halt. It’s an end more than an ending. One of many, and loose as gets.

Something similar often happens in Davis’s micro-stories. It’s another reason why she is at odds with much of contemporary micro-fiction, especially written in English. According to Nelles, the protagonist of a micro-story is typically two-dimensional, a flat character. “The nuances of individual perception and psychology have become irrelevant.” If Davis is interested in one thing, it’s the nuances of individual perception and psychology. They’re usually examined in forensic detail. How very scrupulous this observation in “Liminal: The Little Man,” for example:

Outside a mockingbird sang […] She heard him every night, but was not reminded every night but only now and then of a nightingale, which also sings in the dark. The mockingbird sang, and behind it was the sound of the ocean, sometimes a steady hum, sometimes a sharp clap when a larger wave collapsed on the sand, not every night but when the tide was high at the time when she lay awake in the dark.

It’s a level of precision that makes me trust a narrator. I trust she has something to say, even about things that, at first sight, are aggravatingly banal. Consciousness goes the same way as perception: “At a certain point in her life, she realizes that it is not so much that she wants to have a child as that she does not want not to have a child, or not to have had a child.” This is “A Double Negative.” The whole story.

So here’s my two cents’ worth. If I’m not bored to tears reading Davis’s micro-fiction, I think it’s because the phenomenal world she depicts is mundane, yes, but also deeply fascinating. Because I cannot escape it any more than Davis’s narrators and characters can. Nothing feels more familiar to me than this phenomenal world. At the same time, nothing feels stranger and more fantastic. And that’s what she so strikingly portrays. The everyday miracle of this world. This dazzling prison we’re in.

If Davis increases the tension in her stories, it’s often in this sense. Narrators begin obsessively to analyze and overanalyze, to correct and re-correct the workings and motions of their own mind. They rattle on and on, bringing up incredibly detailed reports from the underground of consciousness. How many rooms it contains. How we get from one to the other. On the page you see endless subordinations and juxtapositions. And no vocabulary shall be varied.

A structure of repetition and alteration ensues, in which the narrator incessantly redirects her own analysis. A real Davis fugue. “Affinity” is one such fugue. It consists of one tireless sentence that attempts to explain why we feel affinity with certain thinkers. The narrator of “Go Away” spends the whole micro-story trying to assess what exactly someone meant when he told her to go away, and how it is she feels about this.

But though he does mean “Go away,” he does not mean it as much as he means the anger that the words have in them, as he also means the anger in the words “don’t come back.” He means all the anger meant by someone who says such words and means what the words say, that you should not come back, ever, or rather he means most of the anger meant by such a person, for if he meant all the anger he would also mean what the words themselves say, that you should not come back, ever. But, being angry, if he were merely to […]

– etc., etc. It’s phenomenological precision to the point of absurdity. The smallest of moments is broken down to its constituent parts. Every last building block is identified. Davis lifts it out, dusts it off, and puts it down where you can see it. It’s not just that it’s psychologically revealing. It’s so psychologically revealing it makes you see things anew. What you thought was familiar, turns out strange. You’re surprised at a flood of thoughts, feelings, and impressions you usually don’t notice is there. You wonder at the everyday twists and bends of a mind that is also your own.

Three random writers walk into a random bar. They are apparently without emotion. One begins to investigate the doorknobs. Another takes an interest in the bottom of her glass. A third in the soft middle part of her palate. They pay very close attention. They are fascinated by everything that happens, which is nothing much. They don’t speak. They leave.

Author’s Note: The author would like to kindly thank Tadzio Koelb for his valuable comments and Wim Michiel for his permission to republish the essay.