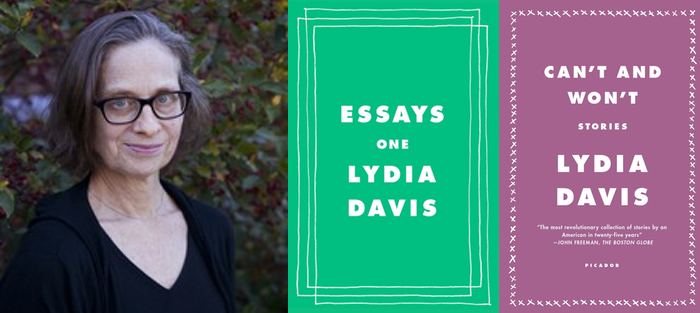

August 3, 2018 was a proud day on planet earth for me. Lydia Davis thought my translation was “fine.” I had an e-mail to prove it. I will repeat it was Lydia Davis who held this opinion. She “particularly liked” how “certain phrases work better in Dutch” and were “somehow more comical,” something I’d noticed as well. It was a beautiful summer day. I considered retiring.

I’d translated one of Davis’s stories for a Belgian magazine called Deus Ex Machina. For some time now, Davis has been my golden standard for—well, many things. Accuracy in word choice and imagery, for one. Thoughtful attention to the texture of language, for another. A fine sense of rhythm and melody. The list goes on, but these might help explain why she’s known as a brilliant translator (of Proust and Flaubert, most famously) and why she received the 2013 Man Booker International Prize for her own work, which includes a novel and a mighty big collection of stories, many of which very short.

She’s best known for the latter. I owe her in this respect. Her work was my gateway into the hard drug of flash fiction. I’ve been getting my regular fix ever since, which is, in Belgium, and, indeed, much of Europe, far less common an occurrence than I sometimes like to imagine. (I recently titled a lecture “Why It’s Okay to Take Micro-Fiction Seriously.”) I also owe Dana Goodyear. I read her article about Davis in The New Yorker and was in the bookshop the same day. This was 2014. How late I was! It was her portrait of Davis as a person that really got to me. Her obsession with language. Her undying curiosity about all things big and, especially, small. Her carefully analytical mind and tendency towards exhaustivity. Her sense of humor. I began to read. I wasn’t disappointed. I found the same qualities in her fiction.

And in her non-fiction. Essays One (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) just came out, a first selection from the essays, lectures, and commentaries Davis accumulated over the years. There’s plenty of interest for fiction writers here. Most of the essays are about writing, reading, observing, or any combination thereof. It’s Davis’s first major book of non-fiction. I was curious. I sent her an e-mail and for a few weeks we went back and forth. I asked her about writing essays and writing short stories, the similarities and differences. I asked her about coherence and digression in fiction and non-fiction. Finally, I dropped all this because a month prior she’d told me that “business as usual” does not seem like an option anymore. So I asked her about our planet, and its climate emergency, and what this means for writers.

Interview:

Sofie Verraest: Essays One just came out. You are mainly known as a writer of stories. Apart from the slim volume Proust, Blanchot and a Woman in Red, this is your first major book of essays. What made you want to publish this book of non-fiction?

Lydia Davis: Well, in a way the answer is quite simple. All these years, I have been writing non-fiction of one kind or another—talks, introductions, the occasional book review, essays on learning foreign languages, on translation, and so on. This work accumulated without my really thinking about gathering it together. Then I realized how much there was and felt it was time for a collection. Actually, there will be two. Right now, while the publisher is preparing the first book, I am preparing to give them the second, which will come out probably late next year.

The texts come from different sources, but they all come together under the heading of “essays.” So, what is an essay for you?

It’s true that only some of the pieces in the book are actual essays in the traditional sense of the word. Some come close to being essays—I suppose you could consider a foreword that describes and introduces the writing of Lucia Berlin, for instance, as an essay that lacks a reasoned and supported, sustained argument. There—have I just defined what I think of as the traditional essay? A piece of thoughtful prose that contains a reasoned, sustained argument or proposition and has an introduction and a conclusion? John D’Agata, however, has put together an anthology of non-traditional essays, in an attempt to show how many forms the essay can take, and thereby broadening the definition of what an essay is. And I suppose that by calling my book Essays, I, too, am forcing many variations of the form to allow themselves to be called by that designation. But really, I use the word for convenience. These pieces are what I have written that is not story, poem, or journal. They are my thoughtful pieces of non-fiction. They are my deliberate, thoughtful, prose responses to other works of fiction, poems, historical figures, and much else.

It’s true that only some of the pieces in the book are actual essays in the traditional sense of the word. Some come close to being essays—I suppose you could consider a foreword that describes and introduces the writing of Lucia Berlin, for instance, as an essay that lacks a reasoned and supported, sustained argument. There—have I just defined what I think of as the traditional essay? A piece of thoughtful prose that contains a reasoned, sustained argument or proposition and has an introduction and a conclusion? John D’Agata, however, has put together an anthology of non-traditional essays, in an attempt to show how many forms the essay can take, and thereby broadening the definition of what an essay is. And I suppose that by calling my book Essays, I, too, am forcing many variations of the form to allow themselves to be called by that designation. But really, I use the word for convenience. These pieces are what I have written that is not story, poem, or journal. They are my thoughtful pieces of non-fiction. They are my deliberate, thoughtful, prose responses to other works of fiction, poems, historical figures, and much else.

In what way is writing an essay for you different from writing a story of similar length? Are the difficulties and pleasures involved different?

This is a difficult question because there are so many different kinds of stories and different kinds of essays, and in many cases they came into being, or were composed, in different ways! The short answer, which doesn’t apply to all the stories or all the essays, would be this: a story usually grows organically from an idea or a first sentence—grows from within, in a sense, driven by an inner necessity as well as a feeling of delight—whereas an essay might more often present itself as a theme or topic on which I will have to organize a coherent argument or development. Thus, approached from the outside rather than growing from the inside out. (For instance, if I have been asked to write a foreword, a review, or an introduction to a translation.) But then, some of the essays, such as those that started as talks for a master class of aspiring writers, did start with a discussion of a certain story, for example, and then grew organically, by association—one discussion suggesting the next in the course of the writing. An essay, too, may be more difficult to begin, and I sometimes experience the same feeling of hopelessness that I used to feel when approaching a university assignment: how will I ever organize this material, and where should I place the emphasis, and what can I leave out, and what should the first sentence be? I don’t feel that same hopelessness or anxiety when approaching the writing of a story.

Do you think this hopelessness might have something to do with the fact that essays are non-fiction? As in: non-fiction implies you accurately depict something, which may imply the idea of depicting it completely (or at least sufficiently for it to be ‘true’). Or do accuracy and completeness also come in when you write fiction?

You ask if the “hopelessness” (which, by the way—as in writing school papers—is temporary, though it can last a long time) has to do with need for accuracy, the depiction of something true. Well, I don’t think so. It may in fact be directly related to schooldays and school assignments. I am gradually waking up to the idea (or realization, if it’s true) that our long years of school have implanted a deep fear of several things: of being late to school, of handing in late work, of not being able to do the assignments, etc. Or I’m speaking only for myself! In any case, no—I think in the case of non-fiction, I have the material all in front of me—though of course there will be surprises as I actually begin to write about it. Whereas, in fiction, I have only a beginning, a starting point of some kind. I have that freedom, no obligation to write to a certain word count, etc., and I don’t have the same task of organizing known material.

So fiction means more unknown material at the start and more freedom to work with it. At the same time, a story also needs some kind of coherence, however minimal. What, in your experience, makes a story coherent?

Yes, a story must have some coherence, of course. It is different in each case. Some of my stories pose a situation and then exhaust all possible permutations of it, and then end—that is one kind of coherence. Another might create a circular pattern: begin with a situation, digress from the situation, or develop it, and then return to the initial situation, but now with a different perspective. Some of my stories are so very short—just a sentence or a line or two—that they are coherent for that reason. Some stay on one subject, for example the imaginary Kafka’s difficulty planning what to make for dinner and then remembering an unfortunate dinner he once gave and then ending with some not very complimentary reflections on himself: it is one long monologue, and its coherence lies in not only the focus on one subject but also in Kafka’s continuing voice. Or a more traditional narrative may find its coherence in the traditional structure: beginning, middle, and end—this is how the relationship started, this is how it developed, and this is how it ended (and these are my feelings about how it ended).

Yes, a story must have some coherence, of course. It is different in each case. Some of my stories pose a situation and then exhaust all possible permutations of it, and then end—that is one kind of coherence. Another might create a circular pattern: begin with a situation, digress from the situation, or develop it, and then return to the initial situation, but now with a different perspective. Some of my stories are so very short—just a sentence or a line or two—that they are coherent for that reason. Some stay on one subject, for example the imaginary Kafka’s difficulty planning what to make for dinner and then remembering an unfortunate dinner he once gave and then ending with some not very complimentary reflections on himself: it is one long monologue, and its coherence lies in not only the focus on one subject but also in Kafka’s continuing voice. Or a more traditional narrative may find its coherence in the traditional structure: beginning, middle, and end—this is how the relationship started, this is how it developed, and this is how it ended (and these are my feelings about how it ended).

How do you get to this coherence in the process of writing (stories, that is)?

It is different in each case, of course. I am working on a story now that is growing by accumulation, for example. I won’t describe it too exactly since I’m still developing it, but it is an ongoing argument, and each day, it seems, I think of another item that comes up in the argument. I add it, and at the same time read over what is already there and change it a bit, if something bothers me. At last I think the topic is exhausted—I could add to the story but enough is enough. The story will be coherent because of the very tight and closely focused way it developed.

In other cases, I might have to make it more coherent in the revising stage of the writing—I might see that I’m wandering off the subject at a certain point, the story is losing energy, I should simply cut part of it out to keep it focused. It’s always a balance, as one writes, between spontaneity, looseness, freedom on the one hand and control, direction on the other. You don’t want either one to be too strong a force.

Is coherence a different thing in non-fiction? How do you make sure your essays are coherent?

I’ll think about the origin, or basic idea, of the word “coherent” (without consulting a dictionary!). To me it means “hanging together” or “sticking together”. In other words, all the parts of it belonging and fitting together. In one sense, there is no difference between coherence in non-fiction and in fiction—as long as all parts of the piece belong together and fit together, it is coherent. We attribute a further meaning to the word, in casual usage—”making sense.” Here, maybe the opposite is useful: in this understanding of the word, something that is incoherent makes no sense to us. A person who is incoherent is difficult or impossible to understand. I might say that the difference in the form of coherence, between a piece of non-fiction and a piece of fiction, is simply a difference in the overall form of the two genres. But already, my generalization can be proved invalid by pointing out that some pieces of fiction—for instance, traditional, formal narrative short stories—achieve coherence in much the same way as pieces of traditional non-fiction. And vice versa: there are formally adventurous, non-traditional pieces of non-fiction that achieve their coherence in much the same way as pieces of non-traditional fiction. Maybe another concept to bring in here is balance. Or, proportion.

And that may answer the second part of your question: when I am reading over my non-fiction, most recently the essays in my new book (and in the book that will follow), I make sure 1) that all parts of the essay are relevant to the main subject of the essay; 2) that the essay has good proportions—in other words, that the opening does not go on for a disproportionately long time compared to the middle and the end, for example; 3) and, perhaps the same thing, or almost, that the balance is good between the parts of the essay—the major parts and also the smaller sub-topics. I do this in two ways: one, by reading and rereading the essay again and again, correcting anything that bothers me; and, two, by holding in my mind a sense of the structure of the whole essay—and this perception, or impression, of the whole is an almost physical sense. I know right away from this sense whether the whole is in balance, is coherent. Then, if it is not, I can work to fix it.

Judith Kitchen believes essays are better suited to digression than stories. (Because they’re non-fiction, the reader feels the presence of the real-life author more and, therefore, would be eager to compare the author’s experiences to her own. This constant back and forth would open up space for digression in the text.) Is this your experience in writing essays?

Well, again, I would say one can’t generalize about essays and fiction. I think of a traditional piece of fiction, perhaps a story by Katherine Mansfield. It’s true that we follow the story closely and aren’t very willing to stop and let our minds wander. But then there is plenty of fiction that is either so dense or so thought-provoking that we do like to stop and think, or bring our own experiences to what we’re reading. For instance, a work of fiction that is not a page-turner, such as Proust’s Swann’s Way. It moves forward at such a leisurely pace, dwelling so long on any one thought or interaction, that we have ample time to put the book down and muse. The non-fiction in my new book takes many forms. Some pieces are over in a minute or two. Others are quite long and work by association, moving straight from a to b to c, so that a reader might want to follow right along, staying close to the progression of the thinking. Others are built in separate, discrete sections, with white spaces between which do invite the reader’s own thoughts. And then there is the phenomenon, which I’ve heard from quite a few different readers, that the very shortest of my “fiction” pieces—just a few lines—allow the reader to add in their own experiences and amplify the piece into something else.

I want to end with a question that has little to do with what we’ve been talking about so far. When I invited you to Brussels for an event, you replied you decided not to fly anymore because ‘business as usual’ does not seem like an option right now. Does the current situation affect you as an author as well? Do you feel it changes anything about the role of the writer?

Thank you for this question, which addresses—instead of “business as usual” as it would have been in more innocent times thirty or fifty years ago (though climate change was already a danger then)—the real subject that should be at the forefront of our minds. Yes, the current situation affects me in every way. A writer is now in the peculiar position of—almost—facing the old “desert-island” question: would I go on writing if I were by myself on a desert island, perhaps the last person alive? Very interesting. Because certainly I have thought that maybe I should drop everything, stop writing, and simply protest permanently in Washington, D.C., outside the White House, which is making such devastatingly bad choices. And perhaps I should. Maybe I’m being a bit cowardly by staying home in my warm, comfortable house, and continuing to write. And what will happen to what I write now, anyway? For a while it might be read, while “business as usual” continues, though it shouldn’t (I mean, business should not continue as usual). But after that, it is quite possible that people will be too busy trying to survive, in one way or another, to read. Or maybe they will continue reading, in snatched moments, to distract themselves. It is hard for me to predict. But I really don’t think that in one hundred years anyone will be calmly reading. So then, am I writing for the culture of the next few years only? Maybe. What I write about will gradually change, I think, because of the current situation. Because, this year, I have focused more intensively on the earth and its life, which we are losing in the world, but which I’m trying to encourage on my own small patch of land, I have begun writing more about the earth and what it produces so generously for us when it is given a chance (even when it is given almost no chance). And I will write about other subjects directly related to our present crisis. As for your question about the role of writers, I would answer that since we have the ability to articulate ideas, that is what we should continue to do. In particular, we should look not so much inward at our own problems or personal history, but outward, at our larger shared communities. And we should be active in our communities to the full extent of our own capacities, reach out to others, speak up.