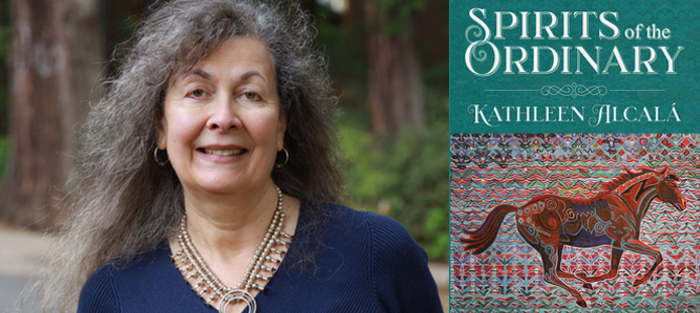

When Spirits of the Ordinary was first published in 1997 by Chronicle Books, critics at Publishers Weekly, the New York Times Book Review, and the San Diego Tribune praised the complexity and mystery of the world Kathleen Alcalá described, a place where Christian and Jewish cultures mixed, a shifting border land somewhere between Mexico and the US in the 1870s. Two more novels followed: The Flower in the Skull (1998) and Treasures in Heaven (2000). Together, the three formed a trilogy, a web of the characters and themes that drive Alcalá’s plots. As for her sentences, they sometimes nearly mesmerize, echoing the sounds and patterns of other languages; they make us feel history, which is very different from understanding it as an intellectual construct.

The title, Spirits of the Ordinary, promises the mystical in the mundane. The subtitle, A Tale of Casas Grandes, refers to the cliff face where Zacarías, the protagonist, achieves enlightenment. The city of gold he has been searching for, “the kind a Spaniard would kill for,” manifests itself before him when the light of the setting sun strikes rock. Seeing this “city from another world, another time,” Zacarías understands the difference between the gold nuggets he sought and the real wealth before him now: “The gold was in the brown skin of the people, the stone, the quality of light upon the cliff face.” An enlightened Zacarías stops searching for gold. He seeks forgiveness and peace instead.

As I wrote for Writer Unboxed, Alcalá’s work offers me, a Latina and a writer, both solace and inspiration. The solace derives from Alcalá’s willingness to write at the intersection of so many cultures (Mexican, Spanish, US, Opata) and so many religious traditions (Christian, Jewish, Islamic). She has the courage to insist that we all have more in common than not; that what we call “reality” is a thin, misleading veneer painted over the mystery that is life. As for inspiration, Alcala’s The Desert Remembers My Name: On family and Writing, a collection of essays published in 2007, serves well. The essays capture the experience of how we remember through our families, through family stories that have been shattered by time and exile from primary cultures. I look at those fragments and despair for what can never be told. Alcalá looks and finds joy, the possibility of orchestrating those fragments, of moving from cacophony to euphony. I am forever in her debt for teaching me another way to see and grateful to speak with her directly about Spirits of the Ordinary, which has recently been reissued by Raven Chronicles Press.

Interview:

Elizabeth Huergo: You wrote in “Pancho Villa Doesn’t Sleep Here,” an essay in The Desert Remembers My Name, that your “stories have been criticized for having unsatisfactory endings. Characters are revealed, but they often don’t take a conclusive action that sums up their existence in the way that American short stories are supposed to end.” The ending of Spirits of the Ordinary strikes me as symphonic precisely because, while it repeats themes, there is no attempt at a very tight summation.

Kathleen Alcalá: I wrote much of the novel sitting on the floor of a ballet studio while my son took piano lessons. There is something about classical music and its movements that seemed appropriate. The music got caught up into the mix as I was trying to express the inexpressible. In a novel or a movie, it’s often silence that communicates what cannot be said through words. I also think the space of the West infiltrates my subconscious. I was trying to give my experience of the West as a wonderful place, not a hell on earth, which is something other writers tend to do.

Intervals of silence, short or long, can trigger so many feelings of loss, proximity, sadness, triumph. Your writing conveys such a powerful sense of history. The way you told the story kept me thinking about the difference between aesthetic vision and expectations, and how expectations are shaped by culture.

Yes, that was important and why I ended up with three novels instead of one. I realized when I got to the material about the Opata, which is in the second novel, The Flower in the Skull, that it had to be told in a different way than the first, Spirits of the Ordinary, because of the cultural setting. The physical settings are the same, but the cultural way of being in The Flower in the Skull required me to tell the story differently.

Yes, that was important and why I ended up with three novels instead of one. I realized when I got to the material about the Opata, which is in the second novel, The Flower in the Skull, that it had to be told in a different way than the first, Spirits of the Ordinary, because of the cultural setting. The physical settings are the same, but the cultural way of being in The Flower in the Skull required me to tell the story differently.

Telling a story differently takes courage.

My editor had enough faith in me to go ahead and publish the next two novels as I wrote them. I initially told Chronicle Books that Spirits of the Ordinary was part of a trilogy. But since I had never written a novel before, nobody wanted to take the chance on a trilogy. So each book was treated as a separate entity as I wrote it.

In terms of telling stories based on cultural differences, do you consider yourself a “magical realist”?

The term became an easy way to classify a set of writings that didn’t match up with North American expectations. I ended up writing/talking a good deal about magical realism in relation to my work. I had already read One-hundred Years of Solitude when I was in college, probably because that was when it was translated into English. I sent a copy in Spanish to my parents, saying, “Look this is just like our family stories!” And they said, “Yes, this is like our story-telling tradition.”

García Márquez observed that what US and European critics termed “surreal” elements in his stories were quite real to Latin Americans. We are habituated to seeing in a particular way by culture and history. What one audience interprets as figurative can be quite literal and devastating to another, an audience that needs to maintain hope for a metamorphosis.

Fiction is all about that moment of transition from one to another state of being. If that metamorphosis doesn’t occur, the character doesn’t change. We, the readers, don’t change. This reminds me of Walter Benjamin, who observes that stories transform the storyteller as well as the listeners. Spirits of the Ordinary was rejected about 24 times before Chronicle Books accepted it. All the editors would say, great book, but we don’t know how to market it. Until quite recently, any Latinex writing had to be the same story about poor people who come up north to work on farms and make good and send their first child to college. That story falls within another story about the Protestant work ethic, the American Dream. This was the story we were allowed to tell. I don’t tell stories about earned success.

There is nothing “ordinary” about your characters, who are often on an alchemical quest. You also explore how religious practices mutate; for example, how a Jewish prayer is hidden in a Catholic one.

Spirits of the Ordinary is a book about the survival of people who considered their primary identity and reason for existence to be Jewish. Rather than abandon their faith when they left Spain under the Inquisition, they changed their practices into something they could carry with them and continue in the New World. I finally have read the historical accounts of my ancestors who came from Spain. I had never made that specific link between Spain and Mexico and how people really did just escape by the skin of their teeth. They were being hunted down by the Catholic church. But the experience didn’t make them saints. Once established in Mexico, they treated the indigenous people not quite as badly but almost as badly as they had been treated. That’s been on my mind lately. This notion, yes, we celebrate survival, but being a survivor does not necessarily make you a good person.

Spirits of the Ordinary is a book about the survival of people who considered their primary identity and reason for existence to be Jewish. Rather than abandon their faith when they left Spain under the Inquisition, they changed their practices into something they could carry with them and continue in the New World. I finally have read the historical accounts of my ancestors who came from Spain. I had never made that specific link between Spain and Mexico and how people really did just escape by the skin of their teeth. They were being hunted down by the Catholic church. But the experience didn’t make them saints. Once established in Mexico, they treated the indigenous people not quite as badly but almost as badly as they had been treated. That’s been on my mind lately. This notion, yes, we celebrate survival, but being a survivor does not necessarily make you a good person.

I’ve been fortunate that my family always acknowledged its background. Both of my parents came to the US as children with their parents, refugees from the Mexican Revolution. For many people their story begins the moment their families arrive here. That’s only one way of telling their story. When I did the research, especially on 19th-century Mexico, I learned things that were not taught in the California schools where I grew up. The fact that California was part of Mexico before the Gold Rush of 1848-1855; and the fact that there were entire indigenous nations never mentioned at all.

I wrote Spirits of the Ordinary before there was an Internet. I went to Chihuahua to use my Uncle Francisco’s library. That’s how and where I started to put the facts together and form a chain of causes and effects. When I was out promoting the novel, people would come up to me and say they had never heard anyone outside their own family speak about a topic. Or they would notice I used a Spanish turn of phrase they recognized as being from northern Mexico. It was very important to me that readers got that subconscious emotional charge that comes from recognition. I gave them back something they had only heard from a parent or grandparent, something they associate so strongly with the place they come from.

There is also something so universal in those particulars.

Estela could have been one of my Cuban great aunts. In your story I can hear my mother’s anecdotes about growing up on a farm, about her grandparents at the turn of the century. There is an emotional component as well as a cadence, the way you tell that fragment of story and then you transition to the next anecdote without forcing a resolution.

That’s what made me a writer as much as anything. I wanted to hear the endings of stories that didn’t have endings. A family member would tell a story. I would ask, “What happened?” No one would say because no one knew. So I had to write stories.

That’s beautiful. Those open endings critics sometimes object to are actually your way of representing the lost details, the spaces between anecdotes.

When I was growing up these stories were dismissed. They were about a time and place our teachers did not recognize. They brought in other stories and said, “You’re American now, so these are your stories. You must adopt these. You must forget those.” There is no reason, though, for the stories of our grandparents to die just because we speak English now. Stories have emotional as well as practical value.

In my research for The Deepest Roots: Finding Food and Community on a Pacific Northwest Island, I came across these narratives by First Nations women in Canada. Their stories revealed information about how indigenous people coped in times of famine. What do you do when the fish don’t return, or a particular crop fails? What is a secondary source of food? All of this practical information is couched within a story about the salmon offering themselves up to you. These are didactic and practical stories. The stories I tell are not quite like that, but they do carry a world within a world.

Is storytelling a form of healing?Absolutely. This is how we heal ourselves. We remake our world by reimagining it, by sharing our idea of the world. People say: I have a writers’ block. But it’s not because of a lack of stories to tell.

It’s a fear of telling the story.

I spent most of last year unable to write. I consider it a block if I can only imagine the story. Anyone can imagine a story. Writers imagine and get the story down on the page. I was so anxious during the last Administration that I couldn’t focus. I wrote very little during the worst of the pandemic, though in the past I have written through times of personal crisis. I kept thinking we would have to leave the country.

What are your writing habits?

Writing every day worked for Hemingway and Dineson. Dineson advised writing a little every day, without hope or expectations. I don’t write every day, but if I intend to write every day I do more than I would otherwise. I write on the computer. When I am really rolling, I type a draft of a section, print it out, and then go through it by hand focusing on one chapter at a time. I type up the changes and start the process again. I go through many drafts, maybe twelve drafts.

Spirits of the Ordinary is beautifully episodic. The way the episodes are developed and organized gives the story great propulsion. There are points, though, where the episode is a dream or a passage of verse. How did you decide on the organization of those passages?

I have to give my editor credit for that. He was brilliant at telling me to delay a chapter. He has what I call a “cool eye.” We only disagreed on a set of canticles I kept coming across as I did the research. They are by an anonymous writer, probably written by a prisoner in Peru. I translated them, and I fought to keep them in the story. He wanted me to include one canticle, but all nine together tell a story of exile and return.

There are several prophets in the novel. Zacarías prophesizes to the indigenous people; the twins, Manzana and Membrillo, are prophets of sorts; Julio, Zacarías’ father, longs for prophetic skill; Zacarías’ son, Gabriel, becomes a preacher; and you end the novel with a passage from Isaiah (60:1-3). All of them are, like the Biblical Isaiah, split in two: exile and return.

I don’t remember why I selected Isaiah. One thing that’s interesting to me is how differently each person reads the novel. For this new edition I asked a friend, Rigoberto González, to write the “Foreword.” His interpretation is based very much on his own queer identity, and how as a young poet he related to Manzana and Membrillo, characters with fluid identities who adapt in order to survive. Another scholar, Dalia Kandioti, sees in the novel how we, the descendants of crypto-Jews, are narrating our place in the world, legitimizing it by naming it. How has Judaism diffused itself into our lives, our worldview? Claudia Castro Luna, a recent poet laureate of Washington State and a Salvadoran refugee, talked about how worlds are nestled within worlds in the novel, and the role of poetry in social justice, as we think about da Silva in his prison cell, writing the canticles.

I grew up on the edge of the Mojave Desert in a very rural part of southern California until I was six years old, when we moved into town. Every time I start writing a new piece, I write a description of that landscape; it’s as if I have to ground myself in those very early memories and relationship to the land before I move on to the next thing.

Like Didion? She has a way of making the landscape into a character.

Like Didion? She has a way of making the landscape into a character.

The first person I read who had something to say about that part of the world was Didion in an essay, “Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” and it starts out with a description of the landscape. The essay is about a court case in the late 60s, which I remember.

We can’t understand the case and its characters without the landscape.

Her nonfiction is so compelling. She finds exactly the right words that she needs to establish setting and character and not one word more.

At what point did you realize you wanted to be a writer?

I did my undergraduate work in Linguistics at Stanford. I knew I was interested in language. I thought about journalism. My double major at Stanford was in Psychology. I took a lot of courses about how our brain works; how we perceive the world.

As a graduate student, putting words on the page terrified me. I would leave a lot of space between each paragraph. Then I would go back to set them up as “normal” paragraphs.

Why were you separating the paragraphs?

I was afraid. I could only handle what I wrote in these little blocks of language. Now I don’t have a problem.

Fiction or non-fiction, mine were compressed like a rebus. Unpacking and finding a narrative voice was like jumping off a cliff.

I got started in 1979, when I opened up a newspaper in rural western Colorado and there was a contest out of Grand Junction, a Science-Fiction/Fantasy short-story competition. I wrote “Midnight at the Lariat Lounge” [later anthologized and reprinted in Lost Trails: Forgotten Tales of the Weird West] and won. When we moved to Seattle in 1983, I used that story to apply to the MFA program at the University of Washington.

What are you working on next?

I am working on two novels, which I don’t recommend! One is about a near-future alternative reality, Los Voladores. I was inspired by a troupe of acrobats I saw in Aguascalientes, Mexico. The other is a novelized biography of a 10th-century Taifa king in Spain. I was about eighty pages in when the pandemic began.

What is your advice to Latinex writers?

Don’t devalue your own stories. Two of my role models are Ana Castillo and Denise Chavez, who draw on their backgrounds for the work they do. They are fearless. I look at them and know I have no excuse. For years I wondered who had given Castillo permission to write? I wanted to ask her in person. By the time I met her, I realized she gave herself permission. Apparently, that was what I was waiting for, for someone to say, it’s okay. Well, I gave myself permission, and it’s okay.