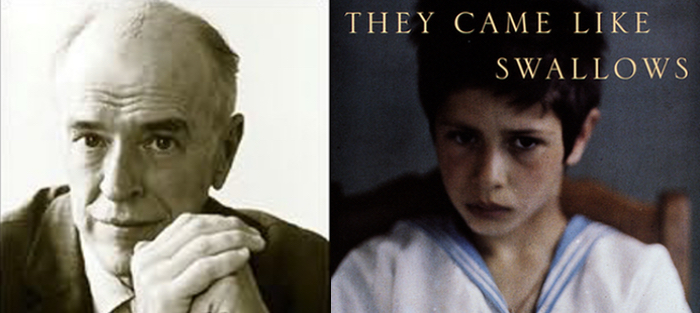

Passing by the old white house on my walk after dinner, I look up at the windows. For as long as I’ve lived in this little town, the place has been empty. But tonight my head is full of history, and now a lonely pair of figures walks from room to room. It is January, 1919. An influenza pandemic has been unleashed upon the world, and in every city and town across America, families are mourning. The worst that could happen has happened—that’s how the novelist William Maxwell, who is ten years old this winter, will one day remember this terrible time, looking back. “My father was all but undone by my mother’s death. In the evening after supper he walked the floor and I walked with him, with my arm around his waist.” From living room to front hallway, where the grandfather clock stands ticking. From hallway to library, library to dining room. Over and over.

A full century after that winter when William Maxwell lost his mother to what has been called the greatest plague in human history, we are again confronting a global pandemic unlike any seen in our lifetimes. Shut away in our houses and apartments, ordered to stay home, we scan our phones for the latest news of COVID19, reach out to comfort friends and loved ones, and in doing so are ourselves comforted a little, at least until the next batch of sobering news arrives. Some days it doesn’t quite seem real. That’s what my daughter tells me when I ask how she’s holding up. This doesn’t seem real. I can’t believe this is really happening. Nothing in our experience has prepared us for this moment. Plagues don’t happen, not anymore anyway. But then I go to the grocery store, only to find empty shelves and shoppers in surgical masks and gloves eyeing one another warily. Driving home, I pass the middle school and see a line of cars stretching out of the parking lot, newly out-of-work parents patiently lining up for donated food so their children won’t go hungry. That same afternoon, my wife telephones on her way home from the clinic where she works, and immediately I hear the exhaustion in her voice. It’s her birthday, but we don’t talk about that. Instead she tells me about the older couple she passed in a hallway today. The man wore a surgical mask and had a Bible open in his hands, and when my wife went by she could hear him reciting the Lord’s Prayer over and over. For those of us whom the pandemic has forced to stay home, the days are mostly an emptiness waiting to be filled: with work and chores, with whatever solitary exercise we can get, with books and movies, with Facebook, Instagram. And with the news, of course—always more news. We do our best to banish the tedium of enforced isolation, while cautiously keeping a storm-eye on the dark clouds on the horizon, which for now keep their distance. For others like my wife, out there at the edge of the storm, or in it, there isn’t this same stultifying stillness. The sick and injured must be cared for, fires still have to be put out, grocery shelves restocked. One day soon, my wife tells me, she may not be able to come home. Dorms are being set up by the university for medical professionals like her in case they contract coronavirus. A surgeon she knows has plans to send his family away to their country home if the need arises, and has offered his house to coworkers afraid of passing the virus on to loved ones. It’s best this way, my wife tells me. Best for us, her family, she means.

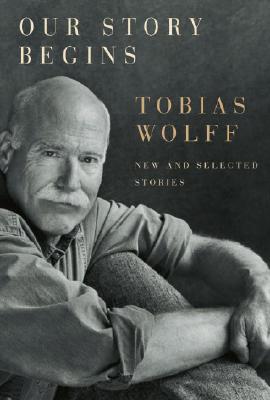

But that stillness I was talking about, which so many of us stuck at home are now confronting. It’s what I can’t help but notice immediately, rereading William Maxwell’s 1937 novel They Came Like Swallows. The book opens on a Sunday in early November, 1918. Eight-year-old Peter Morrison—Bunny, to his family—wakes to the whisper-tap of water dripping from the roof and hears his mother’s voice downstairs. When he hurries into the library to kiss her good morning, his mother asks, “‘Whose angel child are you?’” She is knitting diapers. Discussing his novels, William Maxwell admitted that they were in many ways autobiographical. “They are fragments in which I am a character along with all the others,” he once told the Paris Review in an interview. In They Came Like Swallows, Bunny is essentially the boy Maxwell was in 1918, just as the mother we see knitting diapers on this quiet Sunday is, or was, Maxwell’s pregnant mother, Eva, who turned thirty-seven that year. What we are witnessing then is memory clothed in fiction, memory which will not let go. Pregnant with her third child, Bunny’s mother, Elisabeth, radiates a heavenly tranquility that is already beginning to fracture at its edges. The influenza pandemic which has killed millions all over the world has finally reached their small Midwestern town. Yet somehow, miraculously, this luminous moment between Bunny and his mother isn’t suffused with dread; we don’t sense fear or panic, don’t hear the rumble of approaching thunder. On this quiet Sunday there is only love.

After my walk, I check my phone for the latest news on the plague. It’s March 24th. The United States is reporting over 47,000 confirmed cases of COVID19. Four days ago that number hovered around 14,000. Who knows what the tally will be a week from now, or two weeks from now. Worldwide, the coronavirus has sickened nearly 400,000 and already killed some 17,000 people. Johns Hopkins University has an interactive app on its website which allows you to track the pandemic. There’s a map you can scroll over, with corresponding red circles representing the number of confirmed cases in various countries and states. The larger the circle, the more cases. Italy’s circle is enormous. So is Spain’s, and Iran’s. Four days ago, you could sweep a finger across the broad plains and mountains that span the middle of the U.S. and hit only the odd red pinprick. Now every pocket and patch of the country is turning red, like a leaking boat rapidly filling up with water. At my wife’s clinic, which will as of tonight close down as healthcare providers like her are shifted to the city’s main hospital, every day is a crash course in plague preparedness. Doorknobs and desktops are constantly decontaminated, emergency protocols hashed out via videoconference. Elective surgeries have been cancelled in order to make room for the surge of cases that is expected to begin showing up any day. After work she shows me the blue N95 mask she’s been assigned—one mask, which is all the hospital can currently provide its staff, and on which she’s written her name. She tells me all the beds in the respiratory ICU are now filled. As it has so many times before, our conversation turns to the possibility of her getting sick. Of course she’ll have to be isolated, we both understand. And if her condition worsens? Yes, what then? I tell her I won’t let her be alone. You won’t have any choice, my wife says. She’s right, I realize. What am I going to do, try and fight my way past security? Who’ll look after our children? By now everyone has seen the stories in the news. We all know what happens to people who end up in the hospital with coronavirus. Whatever outcome, good or terrible, you’re going to be alone.

In the winter of 1918, news of the pandemic’s approach was slow to spread. If you wanted to find out where the virus was and where it might be headed, you had to read the newspaper. Radio was still years away, and the suggestion that we might one day track plagues with handheld telephones small enough to fit in a coat pocket would have been met with guffaws of scornful laugher. When the schools in my town closed down twelve days ago, I learned about it by email. When our governor ordered all residents to shelter at home, the message instantly appeared on millions of phones across Michigan. In Maxwell’s boyhood, such public health notices would have been nailed onto church doors and posted in barbershop windows, then passed around by word-of-mouth. Early in They Came Like Swallows, there’s a scene where Bunny is sent to the store to buy a bottle of milk, where he’s told by the shopkeeper, Mrs. Lolly: “In Chicago I hear there’s people dying of influenza. And in St. Louis.” This at a time when much of America was reeling under a second wave of influenza deaths, to the point where funeral homes were running out of coffins. Worldwide, millions had already died. Despite this, Bunny’s family remains untouched by tragedy. For now, on this quiet Sunday, the stillness holds. But we know it won’t last. In fact, a boy at Bunny’s school named Arthur Cook has been sent home sick, we learn. We were playing three-deep, Bunny tries to tell his mother and father at supper that night. And Arthur Cook got sick. But his father won’t listen. There are much more important things to talk about—politics, for instance, and that blunderer President Wilson. “How would it be son,” he tells Bunny, “if you kept quiet until I finish what I’m saying?” And so Bunny does.

In the winter of 1918, news of the pandemic’s approach was slow to spread. If you wanted to find out where the virus was and where it might be headed, you had to read the newspaper. Radio was still years away, and the suggestion that we might one day track plagues with handheld telephones small enough to fit in a coat pocket would have been met with guffaws of scornful laugher. When the schools in my town closed down twelve days ago, I learned about it by email. When our governor ordered all residents to shelter at home, the message instantly appeared on millions of phones across Michigan. In Maxwell’s boyhood, such public health notices would have been nailed onto church doors and posted in barbershop windows, then passed around by word-of-mouth. Early in They Came Like Swallows, there’s a scene where Bunny is sent to the store to buy a bottle of milk, where he’s told by the shopkeeper, Mrs. Lolly: “In Chicago I hear there’s people dying of influenza. And in St. Louis.” This at a time when much of America was reeling under a second wave of influenza deaths, to the point where funeral homes were running out of coffins. Worldwide, millions had already died. Despite this, Bunny’s family remains untouched by tragedy. For now, on this quiet Sunday, the stillness holds. But we know it won’t last. In fact, a boy at Bunny’s school named Arthur Cook has been sent home sick, we learn. We were playing three-deep, Bunny tries to tell his mother and father at supper that night. And Arthur Cook got sick. But his father won’t listen. There are much more important things to talk about—politics, for instance, and that blunderer President Wilson. “How would it be son,” he tells Bunny, “if you kept quiet until I finish what I’m saying?” And so Bunny does.

The houses crowded along my street form a timeline. Mostly there are the houses like mine, built in the 1950s and 60s, but there are also a handful of older houses that have stood here a hundred years or more. The silver maple saplings once planted around the relatively “newer” houses now tower overhead like sleepwalking giants. When my son and daughter were little I would rake the leaves from our backyard maple into hills and let my children dive into them like acrobats. A neighbor with whom I’ve become good friends over the years tells me silver maples are relatively short-lived, and that our trees may be nearing the final decades of life. Is this true? Is it really possible that we will see the end of these magnificent trees? After dinner I walk along the grass two-track alley behind my house and into the heart of town. Again, there’s that patchwork of old and older, with some cottages dating back less than fifty years and some houses as old as the town cemetery, where one sees graves dating back to the Civil War and beyond. Barns which once held horses line the unpaved back alleys. Passing one particularly magnificent mansion, I look up at the intricate scrollwork along the eaves, marveling at the craftsmanship. Blocks away, the old white house sprawls like an abandoned castle. Not so much as a stick of furniture on the front porch, no hedges or flowers in the yard, though the grass appears to be cut regularly, and the paint and roof are in perfect condition. As old houses go, the place doesn’t look haunted so much as completely stripped of life and frozen in time. One almost expects to hear the whinnying of horses coming from the outbuilding in back, and from inside, the deep, resonate gong of a grandfather clock, chiming the hour.

In another of Maxwell’s novels, his masterpiece So Long, See You Tomorrow, the narrator recounts the pall of grief that fell over his house after his mother’s death.

I overheard one family friend after another assuring [my father] that there was no cure but time, and though he said, “Yes, I know,” I could tell he didn’t believe them. Once a week he would wind all the clocks in the house, beginning with the grandfather’s clock in the front hall. Their minute and hour hands went round dependably and the light outside corroborated what they said: it was breakfast time, it was late afternoon, it was night, with the darkness pressing against the windowpanes. What the family friends said is true. For some people. For others the hands of the clock can go round till kingdom come and not cure anything. I don’t know by what means my father came to terms with his grief. All I know is that it was more than a year before the color came back into his face and he could smile when somebody said something funny.

Once, when discussing the novelist Willa Cather over lunch with a friend, the playwright Peter Lemay, Maxwell mused on what caused some people to become writers. Why, Lemay replied, what makes anyone a writer—deprivation, of course. “And then he begged my pardon,” Maxwell later recalled in the Paris Review. “But I do think it’s deprivation that makes people writers, if they have it in them to be a writer.” Having spent most of his life circling the bottomless crater his mother’s death had left behind, a crater into which he flung book after book, Maxwell knew this better than anyone. Even when he tried to write about other things, he couldn’t help but be drawn back to that winter in 1919. “I meant So Long, See You Tomorrow to be the story of somebody else’s tragedy but the narrative weight is evenly distributed between the rifle shot on the first page and my mother’s absence.” The past is never dead, wrote Faulkner. It’s not even past.

None of us knows what these coming months will bring. Shut away in our homes, we sweep our finger over the map of the world, watching those red circles expand. We find new ways to fill the time, ways to hold back the boredom and fear. We hope those we love will remain safe, and when a sudden urge to be outside grips us, when the stillness becomes too much, we walk through our empty towns and cities, and look at the houses we pass, and wait.