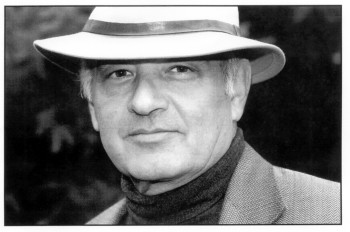

Editor’s Note: In honor of Nicholas Delbanco’s retirement from the University of Michigan, Fiction Writers Review is dedicating this week’s content to a celebration of Delbanco’s influential career as both a writer and a teacher. Delbanco is the author of nearly 30 books of fiction and non-fiction and is the recipient of numerous awards. On December 4th, a symposium entitled “The Janus-Faced Habit: The Art of Teaching and the Teaching of Art” will take place in Ann Arbor as part of a tribute to his legacy.

<hr/ >

“But do you think I can, like, do this?”

At least once or twice each semester a writing student turns up in my office to ask me this. In the enormous old armchair that sits in the corner, they look small, too much like children.

Today it’s a quiet brunette who has missed four classes (mono, maybe) and doesn’t seem to read very much but honestly does have a prose style that sometimes makes me close my eyes and thank the heavens. She’s juggling two jobs and creeping toward graduation and fielding questions about career paths from her father, who has read somewhere that no one reads any more.

“You are doing it,” I tell her, which is not the answer she wants.

“It’s just…” She hesitates, embarrassed by the seeming audacity of her question: “I mean, am I good enough?”

I wish for the thousandth time I had a poker face. The truth is, at her age, twenty-one, almost no one is “good enough” to make it as a writer. The best we can hope for is potential, but potential is a slippery, unreliable thing. I’ve seen too many wunderkinds run out of steam, and some talent-challenged worker bees exceed all expectations. So I’m just not very comfortable playing fortuneteller. What if something I say sends her down the wrong path, and twenty years later she’s miserable, bitter, and destitute? I’m not sure I can carry that kind of burden.

But she’s staring at me, and we’re good, decent people, and what she’s asking isn’t exactly unreasonable. I say, “You have a lot of talent.”

She tilts her head to one side to dismiss the compliment.

“You’re uncommonly talented,” I try again, and she braces herself as if I were a surgeon about to announce the results of her biopsy. “But this is just not a question I can answer for you. If you love writing, you should do it. If you love it so much you would do it for free, then do it with every ounce of yourself and you will already have found success.”

This is the real, end-of-the-line truth. Every serious writer knows that the joy we experience on a good day at our desks surpasses the pleasure found in any publication or award.

This is the real, end-of-the-line truth. Every serious writer knows that the joy we experience on a good day at our desks surpasses the pleasure found in any publication or award.

But a look of defeat shades her young, unlined face, and I know I’ve wounded her. She has come a long way to ask me this question. She has worked up the courage and climbed all these stairs, and here I sit like a cut-rate prophet who refuses to anoint her and speaks only in platitudes. Doesn’t her tuition cover a little more than this?

I go on about how hard a writing life can be, how we are plagued by uncertainty and frustration, how much time and passion and luck are required, how many brilliant writers never publish a single book. But her mood has changed now, and maybe I’m paranoid, but her face seems to be saying, You managed to do it. How hard can it be?

It’s a fair question. It takes me back to two similar conversations I had years ago, when the roles were reversed.

In my second or third year of grad school, a PhD program in Slavic Literature, I reached a particularly low point on the misery scale. My grades were fine, my progress was good, but in every class and task I felt I was in way over my head, and sinking deeper. Finally I went to my mentor, the brilliant and lovely Professor Bogdana Carpenter. It was late afternoon on a gray day in Ann Arbor, but she hadn’t yet turned on the lights in her office, so the air between us grew hazier as I edged my way around and around to this question: “Does it ever get any easier?”

She chuckled and said something along the lines of, “I wish.” When my face fell she shifted in her seat and tried to backtrack, for courtesy’s sake, but soon she wandered into a detailed list of all the hurdles and heartaches that stood on the path between my position and hers. Then she described the tensions and politics and indignities that I hadn’t even realized were a part of her job. She said, “The truth is, it really just gets harder and harder.”

Maybe I caught her on a tough day, I think now, as maybe my student has caught me. But my sense at the time was that Carpenter was trying to say something very kind: “We all have our moments of doubt, of struggle. You are not alone.”

This is a rare admission in the academy, where so much of success rests on the projection of confidence. It seems particularly courageous coming from a female academic of Carpenter’s generation, who had to work even harder to gain respect.

I thanked her for her honesty, though it made me feel even worse. She was one of the most esteemed scholars in her field, tenured at the University of Michigan. And she had always appeared so composed and astute, so elegant in her every insight and action. If she found the job this hard, how could I ever do it?

Looking now at the student in my own dim office, I start to wonder: “What if all she’s asking for is a little bit of reassurance, hope?” What if the thing that comes out of a student’s mouth isn’t actually what she’s trying to ask?

One thing I know, rather than just believe, is that making art, if you love it, is an inherently valuable way to spend our time on the planet. Some people feel this way about gardening or prayer or nature hikes. For me, it’s art—it’s writing. I know art will enrich a person whether they make a dime from it or not.

So would it be so bad if I fibbed a little and lent my student the courage to try that path? I imagine her parents and some of my colleagues, and scores of administrators and Internet trolls, might consider my thinking impractical, even irresponsible.

But with everyone over at the flashy career center waiting to help her with those practicalities, whose job is it to attend to the matter of her imagination?

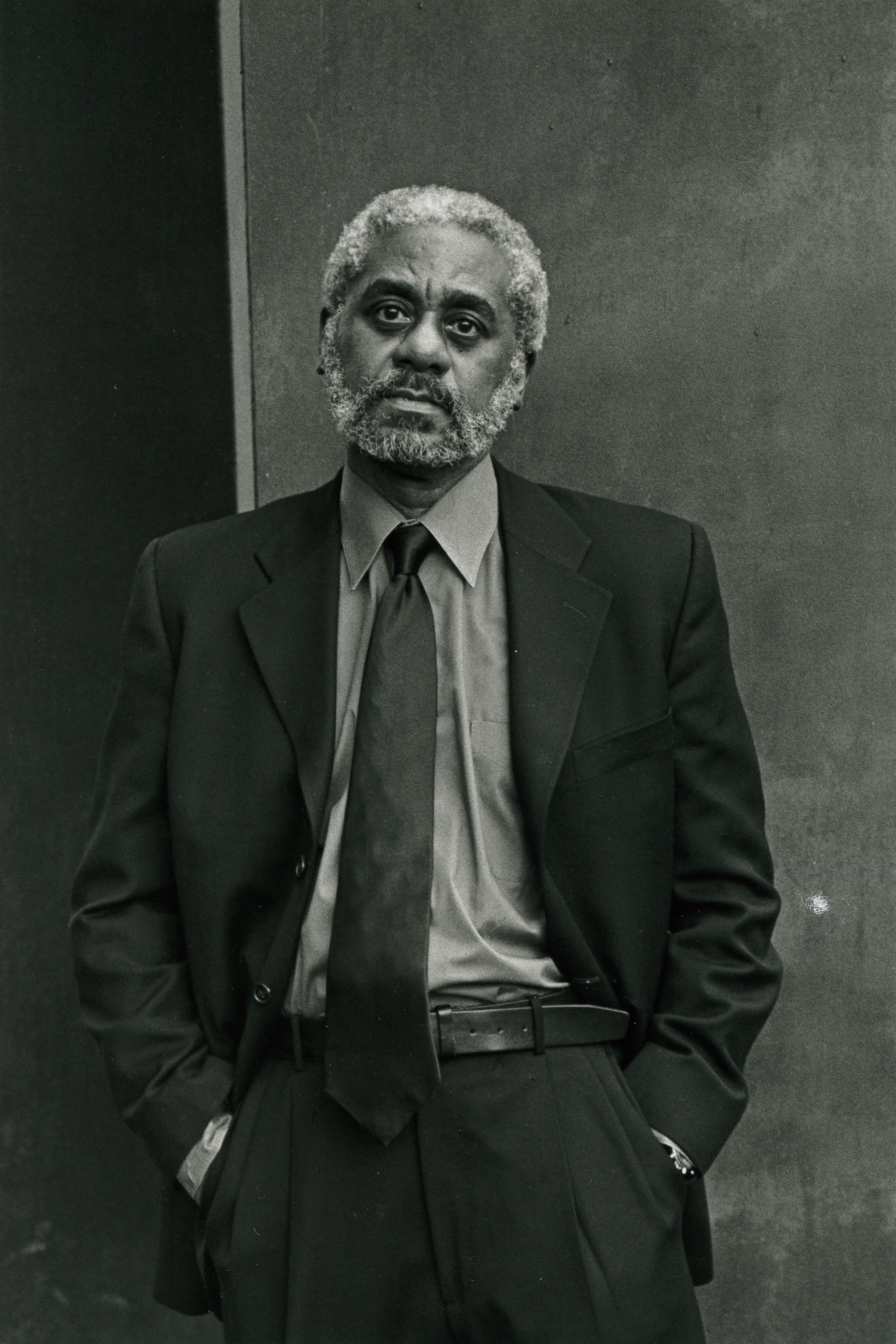

It’s likely I wouldn’t be thinking this way if it weren’t for a second conversation that happened a few months after that first one with Carpenter. My feelings of doubt and inadequacy in the Slavic Department should have made me step up and study harder. But instead I started stealing time away to write fiction, an earlier dream I’d never had the nerve to pursue. I enrolled in a fiction workshop with Professor Nicholas Delbanco, who at the time, and for many years, was director of Michigan’s esteemed MFA program.

Throughout the semester, Delbanco invited, then urged, then shamed all of us to attend the Hopwood Tea, a two-hour hob-nob situation for writers that was held every Thursday afternoon. This kind of socializing with strangers melts the hair off my head, so I avoided it as long as possible. Only at the end of the semester, out of guilt and respect for Nick, did I finally stop by.

Just inside the grand portico of Angel Hall, the Hopwood Room is lined with hundreds, maybe thousands of books by Michigan alumni. There are armchairs and reading nooks and cookies and tea, and underneath many piles of literary journals, a huge round oak table that can seat a dozen or more. The room itself announces, “What we do here, this writing thing, is very important.” As Director of the Hopwood Awards Program, which has given away millions to young writers, Delbanco presided over the Hopwood Room and occupied the large, airy, art-filled office attached to it. When I complimented him on the rooms, he laughed. “I told them if I was going to be asking donors for money, we’d damned well better make it look like we already have some.” His approach clearly worked; he has transformed Michigan from a very good program to one of the best, and best-funded.

Just inside the grand portico of Angel Hall, the Hopwood Room is lined with hundreds, maybe thousands of books by Michigan alumni. There are armchairs and reading nooks and cookies and tea, and underneath many piles of literary journals, a huge round oak table that can seat a dozen or more. The room itself announces, “What we do here, this writing thing, is very important.” As Director of the Hopwood Awards Program, which has given away millions to young writers, Delbanco presided over the Hopwood Room and occupied the large, airy, art-filled office attached to it. When I complimented him on the rooms, he laughed. “I told them if I was going to be asking donors for money, we’d damned well better make it look like we already have some.” His approach clearly worked; he has transformed Michigan from a very good program to one of the best, and best-funded.

Delbanco asked me a lot of questions that day–where was I from, how long had I been writing, how fast did I write, and what was I doing, exactly, in the Slavic Department?

I wasn’t very used to teachers asking personal questions. In Slavic, we mostly transmitted and received information that could end up on tests.

He asked if I was serious about writing. He asked if I could choose to have, on one hand, a published book of fiction, or on the other hand, a tenure-track job in Slavic Literature, which would I want? I laughed and pointed at the book-of-fiction hand, because that option seemed as likely as winning the lottery.

But his face was serious when he said, “Then what are you doing in that PhD program?”

My eyes flared open, my fraudulence again in plain sight. Before I could dwell on it he said, “I have been doing this a long time, and I mean it when I say you have what it takes.”

I had what it took. To be a writer. Said this man who ought to know.

It was like he was throwing me a lifeline.

I doubt Nick remembers the conversation; he must have had it with so many writers over the years. And I’m utterly blank on what either of us said next. All I know is I floated home and told my husband every word. Then I called my mother.

No, I wouldn’t have dropped out of my PhD program and declared myself a writer on the basis of Nick’s or anyone else’s words. But they were a first step, a permission slip to dream, and to commit myself.

Bogdana Carpenter retired a few years ago; Nick Delbanco is retiring this year. The thing about mentors is, you can’t really get the full sense of what they’ve done for you until long after you’ve stopped seeing them regularly. Until you’ve jumped all those hurdles and felt all those heartaches, you can’t fully grasp just how much they were juggling, and how generous it was of them to put down their own writing, their own dreams, and say, “Come on in, there’s room for you right here.”

I set out to write something in Nick’s honor on the occasion of his retirement, and somehow I brought Carpenter along for the ride. And mentioning her makes me want to name all the others, the whole constellation of bright lights by which I steered my course.

They’re on my mind tonight as I write this. My student has gone home, and I’m wondering which of my mixed messages she absorbed. Maybe I should have shielded her more from the difficulties of a writing life. Maybe college should provide not just training for but a temporary shelter from certain aspects of the so-called “real world.” After all, she goes home to it every night. Maybe it’s my job to help her believe there’s another way.

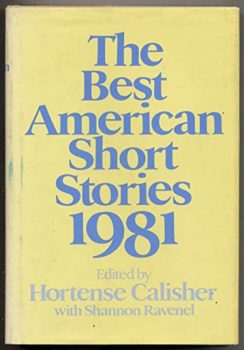

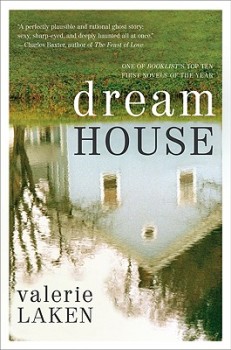

This is one of Nick’s extraordinary talents: making people believe. He’s made a career of bringing together, supporting, and celebrating writers, and in doing that he made them all believe—not just in themselves, but in the value of literature itself. As someone who has published over twenty-five books, Nick seems immune to the wallowing self-doubt that plagues so many writers, and this makes his very presence reassuring. In his nearly five decades of teaching and through the programs he did so much to develop, Nick has thrown lifelines to thousands of writers flailing in the shifting currents of doubt and belief, writers wondering if they were deluding themselves or if they might be the real deal. No, we shouldn’t need outside validation if we love it so much we would do it for free, but especially in the early days, when the best we can hope to have is potential, three words of encouragement can fuel a whole bonfire of hope. Those little milestones at the beginning—an acceptance letter, an award, a first publication—still strike me as the sweetest achievements of all. Without them, the later, grander achievements couldn’t have happened because I wouldn’t have believed they could.

This is one of Nick’s extraordinary talents: making people believe. He’s made a career of bringing together, supporting, and celebrating writers, and in doing that he made them all believe—not just in themselves, but in the value of literature itself. As someone who has published over twenty-five books, Nick seems immune to the wallowing self-doubt that plagues so many writers, and this makes his very presence reassuring. In his nearly five decades of teaching and through the programs he did so much to develop, Nick has thrown lifelines to thousands of writers flailing in the shifting currents of doubt and belief, writers wondering if they were deluding themselves or if they might be the real deal. No, we shouldn’t need outside validation if we love it so much we would do it for free, but especially in the early days, when the best we can hope to have is potential, three words of encouragement can fuel a whole bonfire of hope. Those little milestones at the beginning—an acceptance letter, an award, a first publication—still strike me as the sweetest achievements of all. Without them, the later, grander achievements couldn’t have happened because I wouldn’t have believed they could.

So this is me saying I’m grateful, Nick. (Likewise, Charlie and Peter and Eileen, not to mention Bogdana and Omry and Mila and more.) And I know I’m not alone. There are scores of us spread all over the globe, passing on what we took from you.