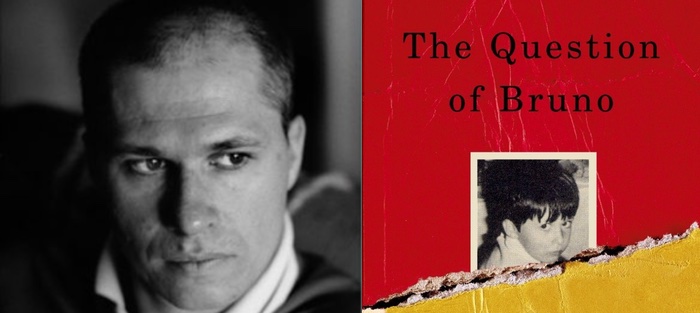

We’re in a disturbingly polarized time in the US, in the world, but there’s a certain sort of flaw that unites humanity: a desire to simultaneously consume tragic news from around the world and ignore it. Maybe it took an accidental immigrant to put this into words as acutely as Aleksandar Hemon did in his first book, twenty-one years old now, The Question of Bruno. Displacement can make a mind go to all sort of reflective places, places a person with recognizable ground under their feet and a clear future doesn’t go.

Hemon, though, has reason to ruminate on, to pinpoint, the very moment when the war that displaced him began. An impossible task, but as far as defining moments—and first shots—go, Franz Ferdinand’s assassination is certainly a place to start. The spanning years and turmoil that follow become only loosely related to the Bosnian war, but were I to spend all day at a soul-deadening job in a city where I am out of place and have no purpose, I might go back that far, too. Hemon’s narrator, himself displaced, as there are many similarities between author and character in this book of short stories, has the time to trace back the lineage.

Hemon, though, has reason to ruminate on, to pinpoint, the very moment when the war that displaced him began. An impossible task, but as far as defining moments—and first shots—go, Franz Ferdinand’s assassination is certainly a place to start. The spanning years and turmoil that follow become only loosely related to the Bosnian war, but were I to spend all day at a soul-deadening job in a city where I am out of place and have no purpose, I might go back that far, too. Hemon’s narrator, himself displaced, as there are many similarities between author and character in this book of short stories, has the time to trace back the lineage.

We know of Hemon, both from biography and as briefly mentioned in part two of “The Accordion,” that he is Bosnian and living in Chicago, stranded and not to fulfill his lifelong dream of parking cars in Chicago. His mind goes fluidly from stories of his great-grandfather to history books he read as a child, connecting the two, perhaps easier to do from a distance, where memory is memory and none of the real is present in a foreign land with no reminders, very few even flashing images of Sarajevo where it should be in the news. This second part, the part of the story where Hemon reveals that the story we’ve enjoyed and let ourselves buy into, is not even based on a story passed down from generations but is in fact not fact in the remotest sense but the product of a vivid imagination and a long train ride. This organization of story and then confession does two things. The first is that for this to be a story of a man who is displaced[1], who is unhappy and alone, the confession must come last. An admission before the story that the narrator is tired from a long day of an unfulfilling job and missing home and family and even to some extent war being helpless and useless in the US—and then revealing that he is a gifted writer and that he has this outlet available to himself—would change the story to somewhat of a happier one, where the narrator gets what he wants, which is a connection to home, even if self-created, at the end.

The second part at work here in this organization of part one and part two is that it allows us to readily buy into the spectacle. Spectacle of war is important to Hemon, it makes a good story but one we should feel a little ashamed to have enjoyed, but Hemon gets huge satisfaction in writing the story that lures us in. It is his obsession as much as ours. Most people don’t entertain themselves at the end of a workday by writing about, and making beautiful, historical events and assassinations, but everyone likes a good war story. It’s hard to turn away from, the gorier and more shocking the better. His creation of a little human-interest story of this famous ride is a harmless daydream on its surface but more telling of human nature underneath. Hemon brings up this spectacle of war more graphically later on in the book, in “A Coin.” Here in “The Accordion,” he—in just a couple pages—plays to our natural eagerness to participate and go along with the “irresponsible imagination and shameless speculation.” It didn’t take us very long at all to suspend disbelief and omit the obvious facts (that Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in a motor car, not a horse-drawn coach) and trust our narrator, a narrator who half a page later reveals that he’s not to be trusted, and we’ve already bought what he sold us.

Hemon’s disdain for Americans looking on at horrors as a way to feel a fleeting pity and do nothing to act is more pronounced two stories later in “A Coin.” Aida works as an assistant to foreign TV companies, “helping them to get by in hell, to approach and bribe government officials, and find good parties” and editing war footage for them, cutting up hours of which only a few minutes will ever be used. These companies are in and out, there for as long as there’s the spectacle of war, and gone as soon as the story is either over or just old. Aida is aware of the need to entertain them. If they lose interest, they’re gone. She says of the cameraman with whom she has been having a relationship, “The other day I took Kevin on a tour of my favorite places in Sarajevo. . . . There is a truce in place these days, which always scares me a bit. . . . I’m afraid that Kevin might get bored and leave.” There isn’t a chance that he’ll stay for Aida or that he’d fall in love with the country or find some other story to tell. There’s only what he can openly gawk at with his camera, and the rest doesn’t sell.

Aida has reservations about what she sends of the footage to the television companies. At first she includes all the gory bits she can find. It’s a mistake most people make when something terrible but common is happening to them to assume that anyone will care enough to take action, that anyone has the energy to come save them based on pure shock and horror and outrage. It’s never like that, though. Americans, the world at large, don’t sit at home, action-less, because there’s a lack of media coverage, they wouldn’t budge even if they knew. (I myself am drinking coffee and eating cake as I write this. It’s not the mid 1990s, so the call to action isn’t quite the same, but it’s not as if my country isn’t involved in its own wars right now, it’s not as if I’m not aware that generations of children are growing up in fear of the sky, that their schoolmates have been massacred by drones, by an enemy that doesn’t even look them in the face. It turns my stomach, and then I turn to the next article, take a sip of coffee, momentary pity forgotten.) And after a few news stories run, Aida realizes this, too. She doesn’t even bother to provide what she used to see as provocative and now sees as the entertainment that it will become. She saves it, though, withholds it from the world, puts it all on one tape, a “montage of death attractions.”

At the bottom of page 129 is a break. I call this part two of the story. Part one is a conversation, though very broken and time-lagged, but it is Aida’s voice, presumably not made up but her real (at least within the bounds of this story) letters or thoughts from Sarajevo. At the bottom of page 129, the narrator despairs, “Since April I have received no letters from Aida. From that time on I had to make up her letters,” and the fiction-on-fiction begins. Suddenly Aida’s reports are suspect, and they seem to become more dramatic, if less graphic. The narrator imagines Aida surviving in an environment that through all of Aida’s descriptions seems beyond the capacity of human strength. He writes for her, “I feel I might burst out into madness,” and “My hair is all gray now.” To the narrator, these are the tolls that the horrors he can’t know firsthand must be taking on the people he left behind. The horrors being so profound that he wonders if maybe they sit around and contemplate how they’d best like to die. On the next page, Aida spends a paragraph defending being shot by a sniper as preferable to being raped. As if that’s a tradeoff anyone should have to consider.

This break is the opposite order from the two sections, fact and fiction, in “The Accordion,” but here in “A Coin,” the break is so seamless (there is no “1” and “2” to announce it) that it’s hardly broken our gaze or disrupted our trance. It is so subtle that we remain willing participants of the spectacle, even as the narrator imagines himself removed, plucked from the scene entirely, safely behind a camera of his own. The bleeding is done overseas. The real living, the fear that we all die in, the adrenaline that propels us, that animates a person to risk life and limb to traverse point A to B, is all in Sarajevo. In Chicago, life is unfeeling, empty, safe but purposeless and helpless. Hemon’s use of italics for the narrator’s part, the part he sees as less real, is an effect that is usually used for letters written within a story. Here the italics belong to the narrator as if his life in Chicago is the aside, but the real story belongs to Aida, and it’s Aida who has the real story to tell.

[1] That his characters are displaced does not show up in the language of the writing, Hemon’s mastery of English a little freakish for his late arrival, except for in some subtle ways. My favorite of these instances is from “The Accordion” when the Archduke announces to his wife that he sees a man with an accordion and the Archduchess “winces, as though he’s delirious.” I imagine Hemon writing on the L, pausing, then leaning to the person next to him and asking, “What’s the word for when someone goes like this” and then making a face as if to say a skeptical “Whaaaat?” and the person sees a squinting eye and the head pulled back, as if in pain, and says, “It’s a wince.”