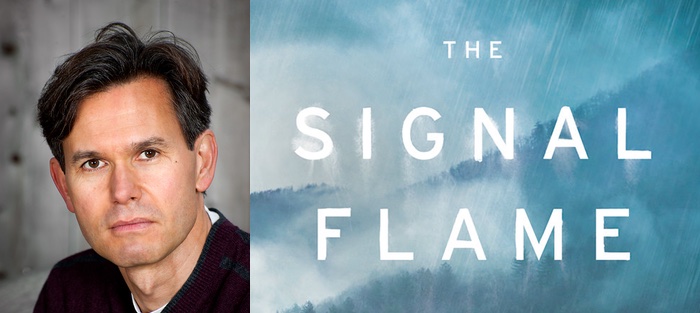

With the novels The Sojourn (Bellevue Literary Press, 2011) and now The Signal Flame (Scribner, 2017), Andrew Krivák reveals inner and outer landscapes peopled by those who live like tempered steel. This is humanity full of shadow and light, beautiful in conception and design—purified as if by fire. Such women and men, made equally of courage and mercy in the face of life’s most fateful and ultimate crucibles, carry readers uncommonly far into places we will remember forever. National Book Award Finalist and winner of the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, Krivák is a writer unafraid to embrace not only complexity, pain, and loss, but also transcendence. The quality his writing brings to mind for me is hope. Hope makes Andrew’s work beloved, and in my experience of him as a person, his restorative and compelling vision of people and the world is equally graced with the will to come through fire together, in order to experience one another in a new light.

In The Signal Flame, with sure clear prose that is by turns rugged as the Pennsylvania wooded wilderness and bright as the day, he reveals a multi-layered inner world in which we grow deeper into love as we understand more fully the intimations that draw people toward one another in the midst of generational alienation. We encounter the will to embody legitimate suffering, and by so doing, become better people. In my experience, few novels contain both an ultimate sense of power as well as the tenderness that helps heal the soul of the world. The Signal Flame meets and surpasses this measure of great literature, and does so with a quiet confidence that is perhaps the central strength of the novel.

In March and February of 2017, Andrew and I engaged in a conversation about the writing life just as The Signal Flame began its journey toward a profound readership. Andrew’s depth of understanding of human frailty and fortitude echoes and adds to the legacy of great moral writers such as Toni Morrison, Shusaku Endo, Flannery O’Connor, Shirley Hazzard, and Graham Greene. I am grateful to Andrew for the gift of this dialogue, and I hope his words meet you with the surprise and delight I’ve grown accustomed to in his life and work.

Interview:

Shann Ray: Your novels present images of family and war that are interwoven, dignified, and that don’t pull punches. What does honesty mean to you as a writer?

Andrew Krivák: Honesty means authenticity, and it’s critical for me as a writer. It’s at the core of good characters and a good story. But how do you achieve that? For me, it has a lot to do with writing about the work a person does, the care he or she takes, or the attention to small things and small acts in the midst of larger events. If I want to write about, say, an Austrian soldier hiking through the Dolomites in 1917, something like the fact that he puts beeswax on his boots to make them waterproof is a detail that illustrates the honesty I’m talking about. You can do all the research you want about this character’s historical counterparts, but it’s the rubbing of beeswax into boots, and sharing rabbit skin mittens with other soldiers that is not only intimate but speaks to a character’s survival. Or may be all the more poignant when that character does not survive. In The Signal Flame, I had my main character, the owner of a sawmill, travel to West Virginia to look at a used ripsaw he was thinking of buying. There’s also a Marine in that same town who was with the main character’s brother the day he went missing in action. I wanted to set up multiple levels of information about these two men, both of whom are excellent at what they do. So I took a few days to teach myself about ripsaws, in order to give my main character a no-nonsense authority. It’s only a few sentences long, but how he looks at that saw speaks to the kind of care he takes in all things. It’s more than realism that I’m after. It’s like a composition of place. The daily hours of characters as they live and breathe, characters who know how to take care as well as take a few punches.

I also strive for honesty in the form of the writing. I want every word to be like a brick placed in a good stone wall, you know? No cracks. No excess mortar. Call it spare, call it economy. I call it taking care to find the best word, to balance a sentence with a feel for the prose, to know when a paragraph has achieved its role in moving the story along. If my characters are going to be good at what work they do in the novel, then I ought to be equal to the task of writing them.

Absence and presence are given deep treatment in The Signal Flame. Sam is gone. Through what he leaves behind, his mark on our lives is indelible. For you, what is the nature of absence and presence in a work of art, in families, in the people we’ve fallen in love with in your novel?

Absence and presence are given deep treatment in The Signal Flame. Sam is gone. Through what he leaves behind, his mark on our lives is indelible. For you, what is the nature of absence and presence in a work of art, in families, in the people we’ve fallen in love with in your novel?

One thing I’ve thought a lot about over the years is the fact of loss in our human experience. We are inheritors of loss, and at the end of it all, a profound sense of loss is first and foremost what we will leave behind for those who love us. That changes over time, once memory begins to fill in the gaps of loss, but this basic fact shapes so much of the arc of our and others’ place in this world. Now, if we take the two characters who are not bodily in The Signal Flame, Jozef Vinich and Sam Konar, they are as present in the memories others carry of them as any other character fully present in the novel. At the outset, Jozef is dead. His loss is mourned and final. Sam, however, is a Marine who is Missing in Action in Vietnam. They don’t know if he is dead, so that uncertainty is both a source of hope and hopelessness. But each absent character in the novel is remembered by those present in ways that accept their absence, while continually insisting on their presence. Right up to the end, like the place setting for Sam at the table of the velija feast, and Bo’s memory of his grandfather telling him the story of the boy who dies in the Italian Alps from The Sojourn. That’s the power of memory. The love for others that keeps memory alive. The old Vietnamese woman mentioned in the story told by Captain Grayson came to me by way of Tim O’Brien. We were in Dayton, Ohio for the Dayton Literary Peace prizes, and when I told him what I was working on, he said, “It sounds like you’re writing a meditation on the missing.” Then he proceeded to remind me that millions of Vietnamese also went missing from their families in not just the American war, but in all of the fighting the Vietnamese had done in their own country since the end of WWII. So, that woman who has been waiting from her son to return from a battle with the French at Dien Bien Phu for eleven years, waiting for him as though he would return whole and unchanged from out of a past that itself had been changed by war, is meant to grapple with that question of, “Who are you waiting for? Who is it that lives in your memory?” Who would Sam be to those who love him, if and when he returned from that war? Inherent in that question is another acceptance of loss. Or, what we find when we engage in a meditation on the missing. So, I strive to keep absence and presence in a balance because we can’t say that one informs our lives more than the other.

Ruth is a new being, symbolizing the body of trauma, the body of love, the body of dignity, self-responsibility, and the will to freedom. Tell us your models in writing of a person with such stunning spiritual and personal bravery. How does she echo her namesake, Ruth, from ancient times?

Ruth is indeed taken from her ancient namesake, Ruth of the Bible. She is both widow and orphan, and the Konar’s take her in. But I was thinking a great deal about my grandmother Anna’s early life when I was writing Ruth. Here was a tall and powerful young woman with four children and a few months pregnant with her fifth, when her husband died in a mine cave in. She raised all five by herself, cleaning schools at night to get by during the Depression. Her version of the subjunctive was finishing a sentence, “with the help of God.” But folks took care of her, when she needed it most, perhaps because of her persistent faith. My father tells the story of one really bad winter when the coal got low and she told him and his brothers to take some wagons and wait by a certain place on the railroad tracks, because Uncle John was coming “down the line,” and he had a little something for them. So my dad and his two older brothers head over to the tracks that ran north and south along the Susquehanna River, and here comes the train, with Uncle John giving them a wave from the coal car. Then he opens a chute for a few seconds as the train rolls by, and when it’s gone, there’s about a hundred yards of anthracite coal on the tracks. They stuffed it in their bags and piled them in the wagons and hiked it all home. More loss, you know? But never loss without that redemptive power and desire of others to do some good, with the help of God.

Why forgiveness? Why not stay with unforgiveness, or at least stay with distancing ourselves from those who have caused us harm? Much of critical gender theory and critical race theory point to forgiveness as codependency, victimhood, and a path to being further harmed. What might be called critical theology, on the other hand, points to forgiveness as liberation, restoration, and call toward atonement, or a return to oneness. Both perspectives, as I see it, dovetail to inform one another and deepen the conversation. Tell us about the reality of forgiveness in The Signal Flame.

Wow. What a tough question. I suppose it’s what you’re taught, and then how what you’re taught lines up with your own experience in life. I don’t know if I’d ever want to live in a world where there was no forgiveness. If you’ve only needed it once, you know what I mean. But then I can’t speak for nations or an entire people. And I certainly don’t want to get in a fight with any literary critics, because I would lose. Let me just say that the forgiveness that is slow but steady between the Youngers and the Konars in The Signal Flame is a simple formula. One person, Hannah, who knows what it is to experience love and loss—who remembers that painful emptying—sees another who is rocked by a loss that is new and raw and nearly total. So she reaches out. Three times she is shown a hand, shown love: in the rain, in the bath, and in the lake. She is able to heal as a result of that, and her healing is as much a part of the novel as the Konar’s waiting for their son and brother. If I could ask people to read one scene in The Signal Flame, it would be the scene in which Hannah gives Ruth a bath. It’s all in that one.

In the end of The Signal Flame, Bo has a vision of his brother Sam. This vision is infused with an ache for brotherhood and sisterhood and love that contains something so visceral it borders on the infinite. Speak to this ending, this elegant finality that transports readers from the concrete expressions of a love that overcomes fire and flood, loss and vengeance, to a love that arrives at a hard-won peace… peace that is, perhaps in essence, beyond us, even as we reach for it from our temporal lives.

This is a good follow-on from the last question. The generational forgiveness that brings Ruth Younger and Bo Konar together fosters their love for each other, though in the shadow of the love that once existed between Ruth and Sam, a love that has been lost to war. Ruth, has in many ways, already laid Sam to rest. But Bo hasn’t. He and his mother are waiting for that signal flame, the ancient harbinger of news about the end of war. And so, although as you so insightfully have read, there is a hard-won peace in the family in Pennsylvania, while the war rages on yet in Southeast Asia, a conflict remains in the brother’s heart. He wants to see Sam. But what will seeing him mean now? Will it be the peace of brothers reunited back in the old homestead? Or maybe, if he is gone, in some better place? Or is Bo aching at once for two loves, both of which will cost him something in the end, regardless of what peace has been achieved? I want readers to see that Bo is utterly alone and conflicted in that final scene. Even though Ruth and Sam are in the dream with him, Ruth is like one of those immovable stick figures that so often occur in our dreams. And Sam is yet a vision on the hilltop, not real until Bo can actually get to him and touch him. In which direction does one turn when that ache divides us? If there is to be a peace in that, it is certainly hard-won.

When you think of landscape, how do you envision its place in the novel, and what role does it play in the lives of Hannah, Ruth, and Bo? How does landscape shape people?

When you think of landscape, how do you envision its place in the novel, and what role does it play in the lives of Hannah, Ruth, and Bo? How does landscape shape people?

Landscape shapes the imagination. I grew up in rural Pennsylvania, in the Pocono Northeast, and lived in the same house on a dead end street at the base of what we called a “mountain” for eighteen years. It wasn’t the most spectacular scenery there is the world, but it has a subtle beauty to it. And you see that when you’re in it all the time. My younger brother and I pretty much lived outside. Our folks didn’t have a lot of money, but there were woods everywhere, and so we made ourselves comfortable in them. We built forts, slept out, fished and shot bows and arrows, pretending we could survive anywhere. We were just kids shaping our imaginations. When I moved away, I lived a long time on the water, around boats, and believed for a time that there was no other place I wanted to be. That wide, subtle beauty, you know? Then, I discovered cities. New York, some Eastern European cities, and London. I loved how cities teemed and were intensely social communities where you could actually disappear. Become a ghost. And now I live in a town outside of Boston, but spend a lot of time in rural New Hampshire, where I wrote a good part of The Signal Flame. You live out west, so you know what sublime landscape looks like. Here, I worry about my kids getting to know the woods. That’s why we have this place in New Hampshire. It’s in the shadow of Mt. Monadnock, which the Transcendentalists loved so well. Every time we go there, I see something that surprises me. The first night we spent there, the loons on the pond were so loud that my kids got scared. They thought they were wolves!

But I’ll tell you a story about a turning point in the novel that made me realize just how important nature and landscape had to be for me. Early on, I was focusing on the people and inventing complicated plot lines among more than one family, and it was going nowhere. At the time, though, I was reading Watership Down to my kids at night. And after one particularly good section, I was thinking about the ways in which Richard Adams wrote the characters of that novel with such a closeness and intimacy to nature, the seasons, the grasses, the ground. What made it come to life so well, I wondered, and it occurred to me: Rabbits! It sounds obvious, but he wrote from the perspective of what a rabbit saw. So, I put my many characters down, and focused on Bo and Hannah Konar for a while. What did they see? What did they know? It made me go back literally as well as literarily to the Pennsylvania in which I grew up. And I wrote about what I had seen as a nine-year-old, season after season, on the hills and ponds and along the streams. Trout lily. Hepatica. Old beech trees towering in the woods. The look of a wide-open field after a long winter. Green fern heads unfolding in the spring. At a certain point, I began to imagine Nature as a character itself in the novel, because it emerged from my boyhood imagination as a thing subtle, surprising, and always beautiful.

In what ways does poetry accompany you as you write?

I started out writing poetry and wanting to be a poet. I wrote poetry as an undergraduate at St John’s College, Annapolis, in between having to translate Homer, read Plato, and demonstrate Euclidean proofs in chalk on a blackboard. And then I did an MFA in poetry at Columbia in 1988, during the bad old days on the Upper West Side, before a lot of things got gentrified. I moved down to the city from Cape Cod, where I was working as a yacht rigger in a boat yard. When I think of the people I got to hear talk about poetry at Columbia in those days, it blows my mind. Daniel Halpern and Deborah Digges were my thesis advisors. And I had classes with William Matthews, Paul Muldoon, JD McClatchy, Ann Lauterbach, and Henri Cole. Henri used to make us memorize George Herbert poems and recite them in class. And I remember when Bill Matthews read “Mood Indigo” to us before his great Blues If You Want came out.

Then there was the city. I heard Walcott read at the 92nd Street Y, Richard Wilbur and James Merrill at the Morgan Library, and John Ashbery at more than one gallery. And I loved my fellow students. We were all in it for the poetry, because we knew, unlike the fiction writers, that we weren’t going to make any money at it. St. John’s College introduced me to the great dead poets, but Columbia introduced me to some great living poets. I just read and read, walking down Broadway with iambic feet of everyone in my head. So, it should be no surprise that my first book was a poetry chapbook called Islands. Lots of poems struggling to described a landscape. Some of them about brothers. Then, I found that a good line of prose could be as alive and powerful as a good line from a poem, and I wanted to tell stories. The Sojourn actually began in a notebook early on as a poem called “At a Bend in the Soča,” a long narrative I was working on about my grandfather in WWI. But the lines turned into pages, stanzas into paragraphs, and the story took on a greater depth. I’ve stuck with prose ever since. On the outside, that is. Sometimes, I’ll tell you, inside I’m twenty-five, and it’s all poetry all over again.

Your prose has cadences that feel sacred. What is the role of sacredness in your writing process?

Well, to keep moving on from the last question, I found that good prose can be measured in the same way that poetry can, if a writer is taking care to hear the words, to weigh the line, to let it come from his or her mouth and ear as well as pen, so that it sings. Prosody comes from the Greek word for song. Now, don’t get me wrong. I understand and accept the strict differences between poetry and prose. But when you ask about the role of sacredness in writing prose, I would hold up a sentence from Cormac McCarthy, or Shann Ray even (because I admire your work so much) as quickly as I would hold up a line from Heaney or Milosz. Because there is an equal amount of “po-e-teis”, an equal amount of “making” in a sentence by you, or McCarthy, or Marilynne Robinson. There’s a beauty in the form. Maybe that’s a way of saying that, in spite of the loss that pervades my novels, I hope that readers feel the continual making in the language, the poetry that shores us up against the loss. All creation, all nature, is groaning, St. Paul says. I hope that the cadences you and other readers feel are the cadences of those groans. Because they are sacred.

You’ve lived a rare life, having spent many years in formation toward becoming a Jesuit priest, and following that having lived devoted to marital and family love. How has this progression influenced you as an artist?

Yes, the Jesuits were the direction I took right after graduating from Columbia. I had been working with some Jesuit priests in the South Bronx during the summer, tutoring kids in math and English for high school. The work those men did was a real inspiration to me, when it came to the desire to make a difference in the world. So, after I graduated with my MFA, I moved to Syracuse, New York, and began my novitiate as a Jesuit Scholastic. Eight years I did that, living in Syracuse, back in the Bronx, and in places like Moscow, Bratislava, and the Dominican Republic. To make a long story bearable, though, it was really the vow of obedience that made me believe I wouldn’t be happy in the long run. I found that it cut against that deep desire I had to be creative. To write. To do it no matter what. And no matter how many Jesuit artists, or any artist in religious life you might point to, that kind of life is not conducive to creativity. The apostolic life is a life moving outward, not inward. So, with the blessing of the Order, I left in 1998.

And here I am, married for seventeen years this August, with three kids, eleven, nine, and seven. I have to say, God sure has a sense of humor. But as an artist, the sweep of that life (which I hope still has some way to go yet) has influenced me in these two seemingly disparate but intimate ways: discipline and letting go. Religious life is a discipline. If you don’t find or fall into a daily order, you won’t last. I was struggling with that basic thing in my philosophy studies, when a spiritual director said to me, “If you want to be a monk in the morning, you’ve got to be a monk at night.” And he meant simply that I had to put down the books and the movies and the late night talks and get to bed, so that I could get up at five and take advantage of my most creative and productive time. I still live by that. The Jesuits were always great ones for getting on with it. Do what you were sent to do. And the letting go part is really just a stance of gratitude. When I can’t write because a kid’s been sick all night, or my wife needs me not to close my door and disappear for the morning but to go get a coffee with her before work because she just needs to talk or hold my hand, that’s when I put my head up and say, “Sure, let’s go into town and get a coffee.” Because that’s what matters most in the moment. So, that’s where this strange journey has brought me. To a place where, in the end, I want them to say about me, “He loved his wife and laughed with his children,” rather than, “He wrote The Signal Flame.”

What are the days like for you as you build toward the next work of art?

My three children are still school-aged, so while I can get some work done in the early mornings, 5-6:30, the bulk of the waking hours are dedicated to getting kids out the door. Then, when I get back home, I sit down to write. Which now means that I’m back to doing research, outlining, and throwing clay on the table, hoping to have something I can shape when the time comes for shaping. And yes, to anticipate your question, I am writing a trilogy. There will be a third and final Dardan novel. But no specifics allowed yet.

What are your favorite aspects of the writing life, and what do you most dread?

Bellow says to Roth in a letter somewhere, that they have the best job in the world as writers, because they get to be alone in a room with words. That’s me. That’s where and when I’m happiest, except for when the people I love draw me out of that room. What I dread most, truthfully, is when a book is done and the publicity starts. I am the world’s worst self-promoter. I’d rather just go on talking to you about sacredness and loss and poetry than post the next reading I’m having on Facebook. But seriously, that’s not a bad problem to have as a writer, is it? I’ll tell you, most days I feel pretty damn lucky that I get to do what I do.

Editors have an important, if often hidden, hand in drawing out the best in writers. Tell us about your relationship with your editor. What have you learned that you can pass along to other writers?

One of the things I love about writing is getting good feedback from my editor, then sitting down and digging in to make the changes. That’s just thrilling to me, especially when it makes a story come to life. And I love that because I have an editor who sends me the good stuff. She really stuck by me and encouraged me to keep at it when I really wondered myself if this novel would ever see the light of day. That’s what I would pass on to other writers. If an editor has chosen to work with you, you have to believe that he or she has your best literary interests at heart and has seen a few stories prior to getting yours. So step back, listen, take a second look, and don’t be afraid to kill your darlings, as they say, in the interest of the story. A good editor is always interested in a good story.

What are your best ways to take a break from writing, to restore the wellspring?

I open-water swim when it’s warm, run and cross-country ski when it’s cold, and fish whenever and wherever I can. I guess the answer is that I go outside.