To be pulverized is to be fractured, to be led through a process in which the essential contained embodiment of an object is shattered with such force that the body is fundamentally changed, altered, or ground to dust. Painter Makoto Fujimura’s works, some as small as the palm of a hand, others vast and corporeal, ranging to 33 feet by 11 feet, follow a process of pulverization in their creation. Fujimura was trained in the ancient Japanese technique of Nihonga in which earthen materials such as malachite and azurite, silver and gold are pulverized and mixed with animal glue to form a palette more subdued and radiant than any I’ve ever seen. They burnish and deepen over time. Pulverization leads to diminishment, elemental solidity to greater fluidness characterized by quietness. In this space the sisters and brothers of quietness attend us: patience, anticipation, awe, desire, drawing the viewer close, taking us deeper into silence.

Silence, then, can lead to beauty.

Silence, then, can lead to beauty.

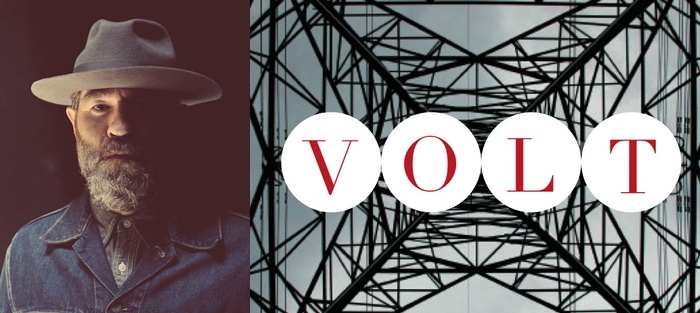

Alan Heathcock’s palette as a fiction writer is no less illumined. He takes as his central ethos the pulverization of the human form until it arrives at a place of death or sleep, in body and spirit, before it awakens again. The luminous text Heathcock achieves with his prose is uncommon in contemporary American letters. Heathcock followed a National Magazine Award in short fiction with a stunning and critically acclaimed debut collection of eight chiseled stories called Volt (Graywolf, 2011). Pulverization is an echo of mortality, and perhaps also a subtle harmony in fiction that beckons apocalypse. Notably, the American West, sutured as it is with rail-lines symbolic of the cold mind of manifest destiny, features heavily in Heathcock’s sensibility in “The Staying Freight,” the first story of the collection. The weight of westward expansion, heedlessness, and loss, places profound pressure on the story, and succeeds in the kind of gravity that embeds the story more in the body than the mind, like a thorn the flesh harbors for years. Later in the collection, a quirky fierce female sheriff speaks true: “You think some are just bad or evil or whatnot, but somewhere along the way they was someone’s baby, suckling the teat like anybody. Then something puts a volt in ‘em and they ain’t the same no more…”.

“The Staying Freight” first appeared in the Harvard Review, and shows a man named Winslow plowing his fields: “Dusk burned the ridgeline and dust churned from the tiller discs set a fog over the field.” The pulverization comes early. “Winslow simply didn’t see his boy running across the field… [He] dabbed his eyes with a filthy handkerchief. The tiller discs hopped. He whirled to see what he’d plowed, and back there lay a boy like something fallen from the sky.”

That beauty lies below pulverization is a view distinctly held by ancient mystics of the east and west. That a writer from Idaho by way of Chicago creates work that aligns with mystic pronouncements by housing such grace and power in the bodies of everyday men and women is astounding. Heathcock’s Winslow moves like an ancient creature through shadowlands known only to the interior of those who have suffered unnamable loss. Who is Winslow’s dead child? What can be done when we’ve killed, accidentally or unconsciously, our own children? Winslow, unable to bear the weight of his grief, abandons his wife and home and wanders in a wasteland in which he must continually face pulverization, finally ending in a place where he earns his keep by being the physical whipping post for the violence of other men.

“I got a deal for you,” Ham said. “So just hear me out.”

Winslow gripped the cleaver. Gave Ham his eyes.

“You’re about the toughest fella I ever knew, and now”—he jutted a thumb out at the corral—“these boys want to bet a hundred bucks their boy can knock the wind from you with a punch.” Ham rapped his knuckles on the block. “I know this boy. He’s as big as a bus, and just as big a pansy,” he said.

“What’s say, Red? Forty for you, sixty for me?”

Winslow’s hands glistened with blood. He disgusted himself. I deserve this much, he thought. He lay down the cleaver. Nodded to Ham.

As the days progress, the violence escalates: this truism echoes the current state of American culture, and perhaps the inevitable murmur of homeostasis in American life. In a landscape in which suicide and homicide are more and more enacted by the bodies of white men, Heathcock’s visceral wisdoms extend into the heart of dominant culture to exact a tremendous price: redemption gained through identification with pulverization. Historically and presently, dominant-culture America has succeeded in pulverizing nondominant cultures, ensuring a grave association with projected patriarchal fears that has inevitably resulted in genocidal tendencies: from slavery to ingrained structural racism; from massacres of Native peoples to the uncounted contemporary femicide of Native American female bodies; from foreign wars pursued under the guise of justice to the same wars shown to be driven by a capitalistic narcissistic injury that thrives on ravenously securing greater economic gain.

What does art have to say to the death of the human project?

What does art have to say to the death of a child, let alone to the death of nations?

Perhaps mercy.

Consider the powerful and graceful embrace art gives to the beloved. We wait with bated breath to receive her influence. We seek revelatory literature in order to find a new and transformative sense of life. Devotees of fiction that delivers on this promise are always seeking new authors whose work will not only satisfy but also challenge, draw us up from pain, and help us engage the future with greater dignity. Such devotees waited some years for Heathcock’s debut collection, Volt. The same devotees have waited some years again for his debut novel, purportedly complete and held like a gemstone in the safe of a Manhattan editorial office until the time comes for its release. The pulverization we encounter in Volt changes us even as it slowly transforms Winslow and the community of characters who people Krafton, Heathcock’s city of the plains. Heathcock’s debut novel, titled 40, set in a contemporary world blighted by waters that rise to a flood of Biblical proportions, promises to engage the heart of the beloved with a deepened iteration of the subtle ways beauty emerges from desolation. If pulverization is sometimes the harbinger of apocalypse, Heathcock’s forthcoming novel is sure to be an apocalypse in which valleys rise, mountains are laid low, and the crooked is made straight.

Winslow somehow finds a way home. He walks past the open door to his son’s room, to his own room to find his wife Sadie. She’s not there. He returns to his son’s room and opens the door as light from the window shrouds him in a soft metallic sheen.

His wife is curled inward on the twin bed:

There Sadie slept, the covers drawn to her chin.

He glanced down at Sadie. Hair fell loose across her mouth. Her eyes were open, staring up at him.

Winslow held his side and lowered himself to the floor. He rested his cheek on the mattress. Her eyes stayed on him. Slowly her hand emerged from the covers. She brushed the hair from her lips. Those same fingers reached across the mattress. Winslow closed his eyes. He nuzzled her hand. She didn’t pull away.

Alan Heathcock’s work begs the question: who is America’s child? Listening closely to the questions Heathcock’s narratives give rise to might cause us, after deep reckoning, to walk homeward, step by step like Winslow, until we are held again in the arms of the beloved. A new day is near, promising to be as filled with dark gravity as ever. Like the multitudinous star fields that encompass the known universe, Heathcock’s universe is made not only of dark material, but light—light that is nonbinary, unified, and held in the gravity of darkness, conducting life. Heathcock’s stories keep our feet firmly planted on earth while at the same time helping us transcend ourselves and reach toward heaven. He’s working on the end of time now and it’s a strangely beautiful feeling, standing here with others on the rim of the world, waiting for the apocalypse.