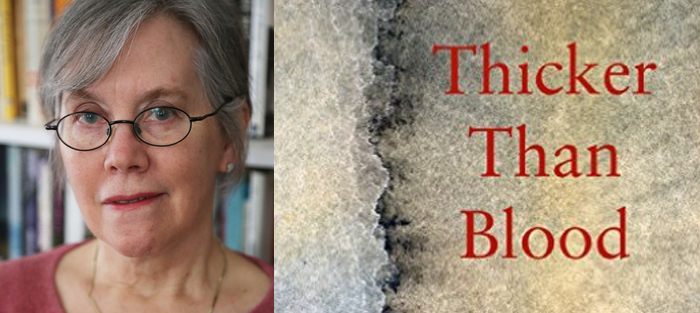

I had the pleasure of meeting Jan English Leary back in the early 1990s when I joined Fred Shafer’s writing workshop in Evanston, Illinois. Jan had already been working with Fred for a few years and was writing lovely, well-polished stories, primarily about teenagers and their troubles. For years now, Jan has been dedicated to doing the hard work of exploring her characters’ depths and describing what it is like to be young in a world where children often feel pressured to grow up fast. In her debut novel, Thicker than Blood (Fomite), Jan explores the ways a mother and daughter respond to transracial adoption. It is a beautiful, moving book that anyone interested in reading about the intricacies of family will enjoy.

Interview:

Katherine Shonk: In your novel, Thicker Than Blood, you portray the adoption of an African American baby, Pearl, by a white woman, Andrea. What drew you to writing about adoption, and transracial adoption in particular?

Jan English Leary: My mother was adopted. I was told this at an early age, and the fact that none of us knew anything about her family of origin or her medical history has always been a part of our lives. After she died, we found a sealed letter in her safety deposit box, and on the envelope was written, “Destroy upon my death.” Although I was deeply curious about it, my father decided to honor her wishes. The good news was that her adoption papers were next to the letter and listed the names of her birth mother and the man who paid her medical bills. I started an ancestry.com search and to find out information about her family of origin. That led to the names of distant family members and a Xerox of a very grainy photo of my birth grandmother, and her obituary, which said she died at 55 in 1961. I wonder what my mother would have felt about the information I found.

The novel started with the idea of that letter and why someone would keep a letter that no one would be allowed to read. I originally wanted my character Andrea find such a letter, open it, and learn that her mother had given up a baby for adoption at birth. I then decided instead not to let Andrea see the letter, not to have any notion of the secrets of her mother’s past. Not knowing is a big part of the life of an adoptee, so I decided that Pearl’s birthmother would abandon her at a church so Andrea and Pearl would not know anything about her origins.

Several years ago, I’d started a story that dealt with a transracial adoption of a Latin-American girl by a married white couple. Over time, the girl became black and the adoptive mother became single. When I found Andrea and Pearl, I realized I’d been gestating this relationship for years in other stories over multiple drafts. I figured the stakes would be higher, that the mother and daughter would have more challenges, with a transracial adoption. It’s that simple. But it allowed me to deepen the material in ways I hadn’t predicted.

My understanding is that Thicker Than Blood changed in some significant ways between the first and final draft. Could you talk about its evolution—why you allowed certain threads to fall away and others to develop?

I never thought I’d write a novel. I am a passionate devotee of the short story and had written them exclusively for years, publishing nearly twenty stories and compiling a collection. However, I knew that novels had a better chance of being published than collections, so I decided to leave my short-story group and to tackle the novel group. Fred Shafer, my long-time mentor, led both groups, so I knew he’d show me the way. I flailed around, writing chapters that seemed to go nowhere. I missed the tight arc of a short story. Then I decided I’d write a novel in stories, a decision which I hoped would bridge the gap, allowing me to write short and long at the same time. For the next couple of years, I worked on stories each with a short arc and a conclusion, but with Andrea and Pearl as central characters. It allowed me to shift point of view and to start and stop without having to keep the thread going.

However, I found that the material from other chapters would creep in or that I needed to reestablish the issue of race in each chapter. Gradually, I broke down the barriers and let in some of the material that I’d been trying to keep at bay. Of course, Andrea would think about her best friend Freya on a daily basis, and Andrea’s relationship with her boyfriend Mike would figure in her thoughts throughout. Whereas in the stories, I’d avoided cluttering her life with too many characters, I was now free to have her think of others and to let them in. The arc stayed the same, the chapters kept the same order, but I let the barriers soften so the ongoing threads could run through more easily. As I incorporated new material, I also removed most of the repetitive expositional material. It felt very liberating.

Which did you enjoy more, writing the first draft of your novel or revising it, and why?

The hardest part was what I mentioned before, the flailing around before I had a sense of the shape, as Antonya Nelson calls it. I think the most rewarding time came when I fully committed to its being a novel and could take the already formed mass and start to shape it more. Definitely, the latter stages of revision were easier than the beginning. I knew the characters. They had a voice and a reality that sustained the writing. Before I knew them, I felt more in the dark. Later on, I could tell myself, no, Pearl would do this, Andrea wouldn’t do that, because by then, I knew them.

Thicker Than Blood is told from multiple points of view. Can you explain how you ended up going this route? Were there any viewpoints that you ultimately chose not to develop?

I knew early on that I’d have Andrea’s voice, and I knew Pearl would have a point of view, but I had to wait until she was old enough for me to be able to render her voice and her view of things. I didn’t want it top-heavy with Andrea’s voice so that was a challenge, and it necessitated my lengthening the time frame so Pearl could grow old enough to have a more mature voice. I knew that there’d be the secret that Andrea’s mother, Nancy, had kept from her, and it had to be told either through a letter or her own memories. Early on, I’d killed Nancy off before the novel started, but then I realized I’d missed an opportunity for interaction, so I kept her alive and let her have a chapter. I briefly considered giving Joanne, Andrea’s sister, one as well, but then I decided that Nancy should be the one whose point of view we should encounter. The last chapter is the only one with a dual point of view, Andrea’s and Pearl’s. I wanted their divergent paths to run closely parallel as they struggled with their estrangement.

How much research did you do for Thicker Than Blood—on transracial adoptions, historical research, etc.? How much of that research made it into the book?

I did a lot of reading on maternity homes over several decades, from the 1920’s to the 1960’s, and on transracial adoption today. I read books, and I talked to birthmothers who’d given up babies for adoption. And I did research on the town where my mother was born and was given up for adoption. That led me to do research on the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company in the tri-city area of Binghamton, Johnson City, and Endicott, New York. My husband and I traveled to the area and drove around, looking at the abandoned factories and doing research in the historical society in Binghamton on George Johnson and Welfare Capitalism. I originally had an additional chapter that took place in the 1920’s, dealing with employees of the factory. It now exists as a short story, but I’m very connected to that material. Because of the letter, I knew the address of the maternity home where my mother was born and although the house had burned down, I was able to envision the setting for the chapter that takes place in 1945.

I also read about the people from different African countries, specifically Ugandans, Burundians, and Rwandans, their history and differences in their cultures. I read about Idi Amin and the torture and abuse he imposed on his people. I also did research on refugee settlement. I talked to a friend who worked at the time for Heartland Alliance, an agency in Chicago that settles refugees and gives them support and job training and was the basis for Breadbasket, Andrea’s workplace. Through Heartland, my husband and I volunteered to help a family from Burundi adjust to life in Chicago.

Andrea is a complex character: She has noble and loving intentions toward her daughter, yet she also has difficulty understanding and relating to Pearl as she grows older. How did you come to your understanding of Andrea’s character?

I was interested in the idea of a mother trying hard to do the right thing but missing the cues about being the parent her child needs. So much of parenting is accepting who your child is, learning to let go of the idealized version of the child you had early on. In fact, the real child is more interesting and rewarding than a fantasy. Andrea is faced with many dilemmas. For instance, she has to decide where to send Pearl to school—the “good” school that’s predominantly white or the public school where she’d have more classmates who looked like her but fewer educational opportunities.

Because of her job as a social worker, Andrea thinks she’s prepared to be the mother of an African American child, but it’s more difficult than she realizes. She is afraid for Pearl and that causes her to be rigid when she needs to listen and be flexible. Where Andrea makes mistakes is in not recognizing soon enough the struggles that Pearl faces, and in not giving her more freedom along with guidance. Pearl is a challenging child, and it’s scary to be her parent. Andrea is at times overbearing and yet naïve. What Andrea has to learn over the course of the novel is to let Pearl guide her, even if it’s not a smooth path.

How did you choose the title Thicker Than Blood?

How did you choose the title Thicker Than Blood?

The novel originally had another title, Endwell, which is the name of a small town next to Binghamton and near the now defunct factory. But that was one of the chapters that didn’t make it into the novel, and so the title didn’t make sense anymore. Marc Estrin, the editor of Fomite Press, encourages collaboration with the authors, and so he had me suggest titles. I sent him numerous suggestions that I’d come up with by looking for significant expressions, lyrics of songs, but nothing resonated. Finally, I did a kind of free association and came up with a long list and sent it to him. He liked Thicker Than Blood and we settled on that as the title. I hadn’t remembered putting it on the list, but it shows that the unconscious is sometimes a lot smarter than the conscious.

What is your writing process: Do you write by hand or on the computer; what time of day do you write, and how often; and so on?

I write on the computer because it’s easiest to get the words out fast that way. At first, there’s a lot of free writing without a goal. Often, I have a sense of a paradox that I find interesting and I list questions to see if I can spark a situation. One trick I have is to tell myself that no one is ever going to see this page and that it’s only practice. Sometimes, when I’m stuck, I start a new file and let fly, just to loosen myself up. After I’ve written several pages, I print them out and edit with a pen, then I re-enter what few good sentences came from that burst of writing. I often start with dialogue and see if I can find a conflict or if a truth can emerge from that. Then I flesh it out with physicality and setting.

I’m a morning writer almost exclusively. I wish I had more staying power to write all day, but I’m best before noon. I belong to The Writers’ WorkSpace in Chicago, a wonderful place to get serious work done. I love being the first person there, to turn on the lights and to claim my favorite chair at a corner carrel. There’s something about going to a place that has no other distractions that helps one produce.

If you don’t mind me asking, what are you working on now?

I’m working on a novel from two points of view involving women who come from the same rural college town but who have very different experiences. One grows up on a farm and marries her high school sweetheart, who’s in the military. The other one is a faculty child who rebels and leaves home after a series of bad decisions. Their lives intersect through a shared history that I won’t reveal here. I know a lot about small-town college life. I need to do research on homeschooling, the anti-vaccination movement, and the lives of Iraq War widows. What’s amazing to me is that I thought I’d used up in the first book all the possible material inspired, admittedly broadly, from my life and family, but I find I have a whole new cache of memories to draw on to inspire new characters and situations. I also love creating a character whose life has been very different from mine. It’s the juxtaposition of familiar and unfamiliar that creates a dynamic energy that propels the story for me.