I met Ben Fountain at the 2008 AWP Conference in New York while we both grabbed a bite to eat and a cup to drink at an overpriced cart that jammed up the hallway. He was a gentleman in the best sense of the word: unprepossessing, not trying to impress himself upon the world, and a snappy dresser (I still remember wanting to trade my suit jacket for his). Naturally we chatted about writing; his first collection of short stories had come out recently, and mine was just about to. He handed me a card with his name and book cover on it, said he hoped to see me while he signed copies at the booth later that day, and then we both dissolved into the crowd.

I met Ben Fountain at the 2008 AWP Conference in New York while we both grabbed a bite to eat and a cup to drink at an overpriced cart that jammed up the hallway. He was a gentleman in the best sense of the word: unprepossessing, not trying to impress himself upon the world, and a snappy dresser (I still remember wanting to trade my suit jacket for his). Naturally we chatted about writing; his first collection of short stories had come out recently, and mine was just about to. He handed me a card with his name and book cover on it, said he hoped to see me while he signed copies at the booth later that day, and then we both dissolved into the crowd.

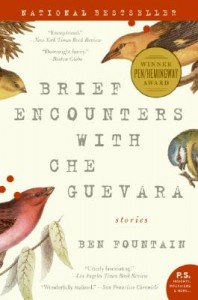

The book turned out to be Brief Encounters with Che Guevara (Harper/Ecco 2006), and as I read its stories I desperately wished that I’d been the one who wrote them. His characters—ranging from a grad student in ornithology who gets kidnapped in Columbia to a soldier who marries a Haitian voodoo deity—seemed to leap into abysses of their own creation, and Fountain followed them all the way to the bottom before watching them climb painstakingly out. I wasn’t the only one who loved the book, as it earned its author a bevy of decorations, including a PEN/Hemingway Award and a Whiting Writers’ Award.

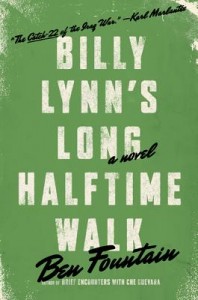

Thanks to Che I’ve been on the lookout for Fountain’s debut novel for quite some time, and have occasionally pestered him by email to find out when it would be published. So when I heard about Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, published by Harper/Ecco just this month, I had to be the first kid on my block to read it.

From the first page, I wanted be the one who’d written Halftime even more desperately than I’d wanted to be the one who wrote Che. The novel grabbed me, started running, and didn’t give me a chance to ask where we were going. Halftime unfolds on Thanksgiving day during a Dallas Cowboys (a.k.a. “America’s Team”) football game, when a group of American soldiers on leave from Iraq are celebrated for their bravery in battle. It turns out that an embedded TV news crew caught a fierce battle on tape, which turned the “Bravo Team” into temporary celebrities.

At the center of this is Billy Lynn, a nineteen-year-old Texan who earned a Silver Star in Iraq but must, like the rest of his fellow Bravos, return there after his Thanksgiving reprieve. Fountain drills into Billy’s life and psyche, not relenting until he has brought all of his protagonist’s dreams, fears, contradictions, alliances, and assumptions to light. The pointlessness and release of war, his own virginity, his miserable wheelchair-bound father, the patriotism that he wishes would be simpler than it has become, the sister who wants him to go AWOL from the war.

At the center of this is Billy Lynn, a nineteen-year-old Texan who earned a Silver Star in Iraq but must, like the rest of his fellow Bravos, return there after his Thanksgiving reprieve. Fountain drills into Billy’s life and psyche, not relenting until he has brought all of his protagonist’s dreams, fears, contradictions, alliances, and assumptions to light. The pointlessness and release of war, his own virginity, his miserable wheelchair-bound father, the patriotism that he wishes would be simpler than it has become, the sister who wants him to go AWOL from the war.

Along the way Fountain sends us into the lives of Lynn’s comrades and the smorgasbord of people he meets at Texas Stadium. There’s Sergeant Dime, who rides his men non-stop but often appears like a mythological trickster, a Loki or Coyote who sees through the world’s folly. There’s Shroom, poor dead Shroom, who expired in Billy’s arms in Iraq and who still offers him, beyond the grave, an alternative way to make America and human life itself add up to more than the sum of its parts. We meet a movie producer who can’t quite land a deal to get the Bravo Squad’s story on the big screen, Beyoncé Knowles (from a discreet distance), the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, and a bunch of angry roadies armed with pipes. Along the way, Billy and his fellow soldiers will gradually learn just how completely they’ve been sucked into the American spectacle-making machine.

It’s as kaleidoscopic and unflinchingly absurd as the novel with which it will most often be compared—Joseph Heller’s Catch-22—or as Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of Night. Fountain’s language, from start to finish, takes brave chance after brave chance as it rages through the book like a storm. I don’t like to throw the “G-word” out casually, but let me say this: Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk is the first great novel of America’s twenty-first century wars.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: May is national short story month, and you’ve made your name thus far as a short story writer. Can you describe your experience of making the transition from one mode to another?

Steven Wingate: May is national short story month, and you’ve made your name thus far as a short story writer. Can you describe your experience of making the transition from one mode to another?

Ben Fountain: The transition started around 1992, and has been painful, slow, and riddled with failure. I’ve got two complete novels in the drawer, along with a big chunk of another, and my only excuse is that I must not be very good at this, and what I’ve managed to figure out about writing novels took me a long time to learn. I think one of the main problems with the defunct novels is that I felt the need to set everything up in logical, painstaking detail—so much backstory before the real story got going, which was maybe my way of being lazy, of avoiding coming to grips with the real story and all the gut-it-out work that would involve.

They say that every project teaches its author how to write it. What was the process like of learning how to write Halftime, and how did that differ from learning how to write Che?

Handling “time” in Billy Lynn was much more of a challenge than I remember it being in any short stories I’ve written. Billy Lynn takes place over the course of one day, but to do what I wanted to do I had to figure out how to slide in significant chunks of past action without, hopefully, slowing down the speed and momentum of the present-tense narrative. There’s one long flashback in the book, but otherwise I found myself going for bits and pieces of flashback, layering those fragments within the present narrative. So maybe I learned a little bit more about how to deal with time in the novel form.

Your relationship to language in Halftime differs from that in Che. It has a load of F-bombs, not only in the mouths of the soldiers but in the narrative voice as well. There’s a go for broke-ness to your language, a verging toward the edge of control. How did you arrive at that?

I arrived at it by the seat of my pants. With pretty much everything I write, the conception of the story seems to arrive with a sound in my head. It’s supposed to sound a certain way, and part of the challenge in writing the story is tuning into that sound, finding the words and rhythms that will get it on the page. It’s always very rough at first, trying to locate that signal, trying to find the right language, and for most of the time you’re flying blind, basically picking your way along.

To write Billy Lynn correctly it seemed I had to find this dense, rude, pummeling, in-your-face sound that maybe–and this is the rationale I arrived at in the course of writing the book—is the sound of the basic insanity of American culture.

From what I can tell of your biography, you don’t seem to have been in the military. But there are soldiers in Che, and Halftime is entirely immersed in the soldier’s world. How do these characters enter your imagination, and how did you inhabit their language and worldview?

You’re right, I was never in the military. So I did what writers always do to appropriate experience that’s not their own—I read everything I could get my hands on, watched all the documentaries, talked to all the soldiers and ex-soldiers who I came across, and generally tried to immerse myself in that world. In other words, research, but that’s just laying the foundation. Ultimately, if you’re to succeed in this type of endeavor, it takes an act—or maybe serial acts would be a better way to put it—of imagination, but you can’t launch unless you’ve done that sort of immersive research. And then you’re also bringing in pieces of your own experience, episodes that might be comparable with the experience you’re trying to imagine your way into. Say, the writing equivalent of method acting? I’m the kind of desperate writer who will use any and every thing that might help me write the story.

After the success of Che, you had a novel called The Texas Itch that never made it off the ground. What happened with that book, and what did you learn from the experience that you could bring to bear in writing Halftime?

The short answer to what happened to that book is that it wasn’t good enough. I’d started that book a long time ago, when I was a much different, and dare I say less able, writer, and despite all my lumbering efforts I couldn’t quite drag it up to whatever level I was operating on once Che was done. Too much backstory, maybe too much labyrinthine plot, and a voice that didn’t quite ring true, or at least fell short too much of the time. I spent a lot of years on that book, many more than I care to admit. The cliche about your greatest strength always being your greatest weakness? That seems to be true in my case—I’m stubborn as hell and find it hard to walk away from anything, but the same hard-headedness that kept me writing long enough that I seem to have arrived at some sort of “career” was also the trait that kept me at The Texas Itch long after I probably should have put it away.

What did I learn that I brought to bear on Billy Lynn? Well, maybe I learned something about compression, about economy of backstory and present narrative. And that I could take a hit like that—having a novel crash and burn in the most spectacular way—and move on to the next thing.

The midpoint sequence of the novel involves the Bravo Squad meeting Dallas Cowboys owner Norm Oglesby, who whips a room full of cheerleaders into a calculated frenzy for media types. You write “The bullshit part of it, isn’t that part of the story too? But not a word, not a murmur, not a peep from the press about how thoroughly they’ve been used this day.” It’s hard not to see this is a critique of American media. I suspect you don’t have a specific “message,” but I’m curious to hear what’s roiling around in your head about media and war.

Right. Well, so much of what passes for “news” in our culture is actually marketing of one form or another, these premeditatively staged public events or PR verbiage that are spoon-fed to and dutifully swallowed by the media, to be in turn shat out into the wider world. I remember something Hunter Thompson wrote about a Super Bowl he was covering, how with all the hundreds or thousands of reporters on hand, with all the tonnage of copy and video stories produced that week, there might be only a couple of stories in which the writer alluded to the actual story that was unfolding, namely, that it was a huge, carefully staged corporate PR event that happened to have a football game attached, and the media were serving as the tacit delivery system for the message that would generate the profits.

My question is, why shouldn’t that be part of the story that’s reported? The experience of the reporting itself, and the varying degrees in which it might be authentic or artificial? Do pay attention to that man behind the curtain.

As for including this line of thought in the book, it wasn’t so much that I have a “message” as that it’s part of the story. To write the story correctly, this needed to be a part of it.

One of your most intriguing characters is Sergeant Dime, who has a complex relationship to the war and to his men. On one hand, he berates his men for representing their country poorly. On the other, he’s an absolute scofflaw who ruins several takes of a publicity video by revealing the true level of violence behind the Iraq war. How did he come to you, and what is he all about?

I don’t think it’s so much that Dime is berating his men for representing the country poorly as it is he stays on their ass because he’s their sergeant, and that’s his job. And, face it, 20-year-old males probably need that kind of constant harassment to stay on task. Dime is part of the machine, but he also has an acute awareness of what the machine is about, and he doesn’t mind sharing that awareness with his men in his own, ah, unique way. I think Dime takes tremendous wicked pleasure in pointing out stupidity—the stupidity of particular individuals, and of the culture at large, and his main method of doing this is speaking the truth. Maybe it’s not so much that he’s on a mission for truth as it is that’s where he gets his pleasure and his energy, by rubbing our faces in it.

Let’s say you can give three bits of advice for short story writers who want to take on the novel. What would they be?

I’m probably the last person who should be giving advice on how to go about writing a novel, but since you asked:

First, and this is obvious but still worth saying, make a close study of the good writers and see how they do it. Read with a pen or pencil in your hand and mark the hell out of the page. Pay attention to the decisions the writers are making, what they decide to leave out just as much as what they put in, and where, and how much, with what degree of directness. Their “technique,” if you will.

Second, don’t wait for that huge block of time to materialize, that chunk of days or weeks or months where you’ll have little or nothing to do besides work on your novel. Those big blocks of free time are hard to come by—harder to come by every year, it seems, the way the culture demands more and more of us. If all you can do is chip away at it for an hour or two a day, well, that’s what you have to do. Maybe it’s the interior equivalent of sailing a small boat by yourself around the world. It’s a long haul, and on any one particular day you aren’t going to make much progress, but if you can string together a bunch of days where you push the book along, after a while you start to see yourself getting somewhere.

Third, don’t make all the mistakes I made.