When I heard about David Heska Wanbli Weiden’s Winter Counts (Ecco/Harper Collins), I knew I had to get hold of it. The novel unfolds in two geographies that are closest to me: Colorado, where I’ve spent more time than anywhere and which is home, and South Dakota, where I’ve lived for the past decade. I figured that if ever a novel would speak to me about the places that shape my psychic outlook, Winter Counts would be it.

It didn’t disappoint. The novel tells the story of Virgil Wounded Horse, a half-Lakota from the Rosebud Indian Reservation who makes his living as an enforcer who metes out justice when authorities will not. When heroin shows up on the reservation, tribal leadership asks Virgil to investigate. His search brings him to Denver to pursue an old nemesis, but he has to return to Rosebud when his orphaned nephew Nathan gets arrested for distributing pills. In true noir fashion, Virgil unravels a nest of lies until he finds the truth beneath it.

But what makes Winter Counts a distinctive title isn’t just its bare-knuckled protagonist and white-knuckled pace. It also explores the borderlands of Virgil’s identity and his troubled sense of belonging to the Lakota community that he has resisted accepting. His journey through the novel’s world involves him learning to let his Lakota and non-Lakota selves move in synchrony, and that stuck with me at least as much as its action.

Winter Counts has been a sensation since its publication in August, garnering positive reviews all over America and going into multiple printings its first two months on the market. Though classified as a crime novel—and certainly part of that tradition—it has spilled over genre barriers into a readership that cuts across the spectrum. Don’t be surprised if you see it shortlisted for “2020 book of the year” when those lists start coming out.

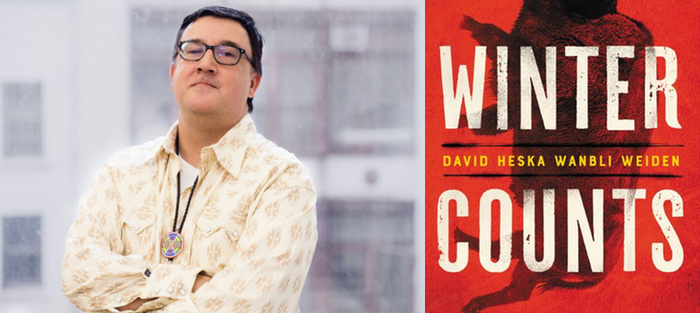

Weiden is also the author of the children’s book Spotted Tail (Reycraft, 2019), a biography of the great Lakota leader and winner of the 2020 Spur Award from the Western Writers of America. He is Professor of Native American Studies and Political Science at Metropolitan State University of Denver, and lives in Colorado with his two sons.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: In your Crimereads essay “Why Indigenous Crime Fiction Matters,” you talk about a variety of indigenous writers who have taken on crime fiction, including Linda Hogan, Louis Owen, Stephen Graham Jones, and Joseph Bruchac. What is your relationship to this tradition, and how much was it on your mind as you wrote Winter Counts?

David Heska Wanbli Weiden: I was (and am) strongly influenced by Native crime writers, and I thought deeply about the question of whether there’s a uniquely indigenous style of crime fiction. For what it’s worth, I believe that Native mystery and suspense fiction tends to be characterized by a focus upon political issues—specifically the effects of colonization on the indigenous peoples of this land—and also by an occasional use of surreal prose and plot elements. But, when I wrote Winter Counts, I was completely focused upon the characters and the story, and not the deeper traditions of indigenous literature. Writing a novel requires a single-minded fixation on the plot and subplots, and I’m not able to consider anything else until I’m finished with the manuscript.

However, after I finished revising the novel (eighteen drafts!), I was able to step back and assess where Winter Counts might fit into this tradition. I’ll leave it to others to make the determination of how I fit into the canon of indigenous literature, but my sense is that my work has more of a legal and political slant than many other works in the genre, no doubt due to the fact that I’m a (nonpracticing) attorney and professor of Native American studies.

You also wrote a New York Times op-ed on federal laws—particularly the Major Crimes Act of 1885—that make it difficult for native communities to enforce the law on their sovereign lands. How has the publication of Winter Counts changed the way you participate in activism and your vision of what might be accomplished?

I’ve been bowled over by the critical reception to the book and the feedback I’ve gotten from readers. I’ve received praise from folks who’ve worked for the federal justice system and also from academics and policymakers. I hope that the novel has helped to start a dialogue about the Major Crimes Act and whether that law should be amended or abolished altogether. That’s been my vision from the very beginning, and my somewhat higher visibility in the public realm may help to achieve this. I’ve tried to use my platform to spotlight these issues, and I hope that the changing political landscape in this country may work in our favor. I’m not sure how likely it is that the criminal justice system on reservations will be reformed anytime soon, but the first step is bringing attention to the problems.

In the Crimereads essay you also write that “Crime fiction is uniquely suited to serve as a call to action for examining structural inequalities affecting Native citizens in the American political system.” This brings up the balance any writer with activist leanings needs to strike between the emotional life of their narrative and their desire to inform and change. Finding the right mix is important, a bit like a carburetor on an old V-8 engine. How do you, in your everyday writerly practice, find that mix?

Ha! I love that metaphor, and I feel like an old V-8 engine myself these days. My sense is that being in the public eye, even in a minor sense, is fleeting for most writers. There’s some attention when a book is released but then folks move on to other things. So, I’m trying to use whatever small interest I’m receiving now to highlight these issues. Of course, I’m trying to keep the writing going, but it’s a challenge, given that I have a day job and two children to raise. I wish I had a great answer to the question of finding the right mix of pursuing activism and art, but it comes down to simply using one’s time as effectively as possible. I get up most days at the brutal hour of 5 a.m. to write, before the demands of the day begin.

Can you talk about your writing process for Winter Counts? How long did it “cook,” so to speak, before you got it into words?

I originally wrote a short story, also titled “Winter Counts,” way back in 2011. That story was published in the literary journal Yellow Medicine Review in 2014, and I moved on to other projects. But the character of Virgil Wounded Horse stayed with me—I kept thinking about how he’d react in certain situations and circumstances. Finally, I decided in 2017 that I needed to take the plunge and try my hand at writing a novel, and so I made the decision to return to Virgil’s world. The characters had thus been marinating, if you will, for some years in my head.

I originally wrote a short story, also titled “Winter Counts,” way back in 2011. That story was published in the literary journal Yellow Medicine Review in 2014, and I moved on to other projects. But the character of Virgil Wounded Horse stayed with me—I kept thinking about how he’d react in certain situations and circumstances. Finally, I decided in 2017 that I needed to take the plunge and try my hand at writing a novel, and so I made the decision to return to Virgil’s world. The characters had thus been marinating, if you will, for some years in my head.

But, once I started writing the book, I came up with completely new characters and plot lines, and the project took off in unexpected directions. I wrote the first draft in about eighteen months and then spent another six months revising the manuscript. After it sold to Ecco, I worked with my editor there and made one last revision. Overall, the process was fairly speedy once I started writing the book. Of course, this was made possible by the years I’d spent thinking about these characters and their lives.

One of the classic opportunities of writing in first person is exploring the character of a narrator who turns out to be something other than who he thinks he is. Virgil Wounded Horse is a man adrift from himself who, over the course of the narrative, moves closer to self-understanding. Can you talk about the process of shaping him, both in terms of the novel’s arc and the arc of your own writing process?

Virgil’s arc involves his rejection of his Native identity and his denunciation of Lakota customs and culture, and his eventual acceptance of indigenous ways as a means to heal himself. But he has some related journeys: deciding to stop working as a hired vigilante and also whether he can return to his previous romantic relationship with Marie Short Bear. All of these are linked, of course, and I had a lot of fun shaping Virgil’s character and his emotional transformation. To accomplish that, I wrote a lot of back story about Virgil that never made it to the book. These journal entries were critical to me in the process of determining Virgil’s arc and the changes he’d make. Of course, all of the characters in the book are engaged in a journey of discovery, and I put in just as much time determining how Marie, Nathan, and even Tommy would change over the course of the novel.

Every fiction writer makes their own deal with autobiography. What experiences of yours have made it into the book, and are there any that surprised you—sneaking up on you in revision, perhaps?

Well, as an iyeska (Lakota slur for half-breed) myself, I certainly drew upon those experiences when writing Virgil’s story. He was relentlessly bullied as a kid for being an iyeska, and it created a lot of his anger and resentment. Although I didn’t have it as bad as Virgil, I did tap into my own feelings of being an outsider, and I think that experience resonates for many of us.

What surprised me were the scenes involving Nathan, Virgil’s fourteen-year-old nephew. When I started writing the novel, my own children were quite young, and Nathan’s character was completely drawn from my imagination. Yet I discovered that my own son, David Jr., was a lot like Nathan when he hit his teen years (although David Jr. certainly doesn’t mess around with hard drugs.) I found myself writing scenes with Nathan that were drawn, in some way, from real life. For example, Marie’s back story of wearing wolf ears and howling in elementary school came from David Jr., who told me about his classmate who did just that. In so many ways, my actual life as a parent and Virgil’s fictionalized guardianship came to resemble each other, in spirit if not in the details.

You received your MFA in creative writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts, which at less than a decade old has produced some quite accomplished writers—yourself and Tommy Orange, for starters. Could you talk about the program, both in terms of your personal experience and what it means to indigenous communities?

Photo by Aslan Chalom

The Institute of American Indian Arts was critical to my development as a writer, and I’m so grateful I was able to study there. I was actually enrolled in another school, but transferred to IAIA when I heard about their new MFA program. I was in the very first class at IAIA, but I took a hiatus and didn’t finish until 2018. By then, students like Tommy Orange and Terese Marie Mailhot were streaking across the literary landscape, having graduated a couple of years before me.

The success of students from IAIA is a testament to the importance of the school for Natives around the country. Most tribal colleges draw from local populations, but IAIA is truly national in scope, and I studied with students from various Native nations in the U.S. and Canada. It was a joy to be able to discuss indigenous issues with other Native students, and the faculty were superb. As you note, the school is quite new, but has graduated a fair number of accomplished authors. I believe this speaks to the need for education that is designed for indigenous students and students of color. Many commentators have lamented the lack of diversity and inclusion in most MFA programs, but I believe a change is beginning to occur.

There’s something eerily similar about the characters in this novel who sell stuff. Whether it’s coffee, legal marijuana, teen detention centers, or indigenous food, they’re all bullshit artists with an eerily similar schtick. It made me think of what I’ve heard from Lakota up here in South Dakota: The white man is always selling you something. But in this case, it’s not just the white man who’s doing the selling. I’m not sure I have a specific question here, but I’m curious to hear you rap about how that schtick plays into your vision of America as it stands today.

That’s so interesting! I never made the connection between the folks in the novel who are all selling something, and the idea that they all have a line or a sales rap. I think it relates to the capitalist system in which we’re embedded, and how many folks seem to be trying to get ahead by selling something, whether it’s cannabis, fancy coffee, or gourmet cuisine. Especially in these times of economic distress, there’s always the fear that we might fall behind, lose our jobs, or suffer some other setback. Although I didn’t consciously intend to write an economic critique, I see now that it’s certainly present in the novel.

Not everybody likes this question (sometimes because they’re afraid to jinx themselves) but what’s your next literary project and why are you drawn to it? How does it compare—both thematically and in terms of writing process—with Winter Counts?

I love this question! I’m so happy to be able to share that I’m currently writing the sequel to Winter Counts. All of the main characters from that book will return, along with at least one new character. There will be a different theme and plot, of course, but I believe that fans of Winter Counts will enjoy it. As far as the writing process, it’s radically different in that I’m under a deadline, whereas I had none for the first book. Naturally, there’s also some pressure to deliver a novel that will live up to the acclaim that Winter Counts has received, but I don’t think about that. Right now, I’m in the really fun stage of determining the plot and character arcs for Virgil, Marie, Nathan, and Tommy.

I’ll close by expressing my gratitude to all who have read and enjoyed Winter Counts! Thank you for this support, which has humbled and honored me.