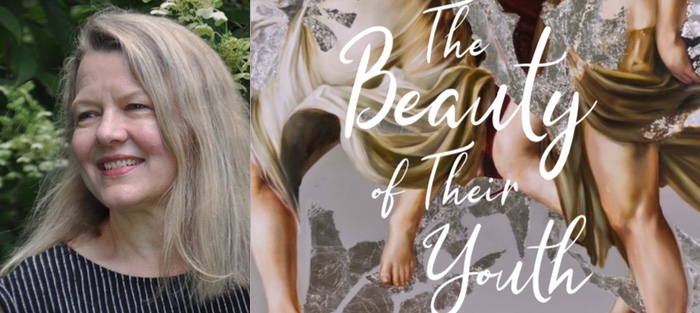

In Joyce Hinnefeld’s latest short story collection, The Beauty of their Youth (Wolfson Press/Indiana University South Bend), people are haunted by what is not physically present: the past, their youth, clarity, and understanding. They gaze back on their histories, or at the person sitting beside them, and find themselves negotiating what it means to be related to someone. Whether those relationships are blood ties, bonds by marriage, circumstance and proximity, or neighborly habit, characters are always trying to understand their relativity to the world and others—and discovering, even after all that life and experience, what they still have to learn.

I met Joyce when I moved to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, over five years ago, and knew right away that I’d met a kindred writer spirit, one with whom I’ve shared enormously fulfilling conversations over the years about words and stories, and the joys and the difficulties of balancing writing and life. I’m so happy to have a chance to talk with her about this collection.

Interview:

Kate Racculia: The stories in The Beauty of their Youth are diverse in character, tone, and voice, though I was particularly struck by how masterfully they employ setting—as a foil, as a character, as a necessary part of the whole. What kind of research went into these settings on the page? And what draws you, as a writer, to create specific places?

Joyce Hinnefeld: The main research for all the stories, really, has been doing what I think most writers do, which is to look and listen, wherever I am, and to try to imagine myself into life in whatever place I’m visiting, or maybe even living in.

That was definitely the case with “Polymorphous,” which grew out of the experience of living in a restored mill along a creek below Easton, Pennsylvania, almost into Bucks County. A number of our neighbors at that time were people (some, though not all, from New York) who’d lovingly restored old Pennsylvania Dutch farmhouses in that area. Others were “old-timers,” like Joan and her husband. And one neighbor in particular was the inspiration for Richard—though Richard was actually a composite character based on that neighbor but also several people I knew when I lived and worked in New York in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was fascinating to me, during that brief period of living in the old mill, to observe how these various kinds of people and their very different worlds came together in that beautiful green valley where we were living. In many ways I felt like an outsider there (I’ve felt that pretty much everywhere I’ve lived, honestly), and yet there was also something familiar, and comforting, about that semi-rural landscape. I think the character of Joan was born of that familiarity and comfort, and her relationship with Richard echoes feelings of my own through the years, connected with being a kind of rural/small-town person in the midst of “city folks”—people whose taste and sophistication were things I sort of feared, but also longed for.

That was definitely the case with “Polymorphous,” which grew out of the experience of living in a restored mill along a creek below Easton, Pennsylvania, almost into Bucks County. A number of our neighbors at that time were people (some, though not all, from New York) who’d lovingly restored old Pennsylvania Dutch farmhouses in that area. Others were “old-timers,” like Joan and her husband. And one neighbor in particular was the inspiration for Richard—though Richard was actually a composite character based on that neighbor but also several people I knew when I lived and worked in New York in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was fascinating to me, during that brief period of living in the old mill, to observe how these various kinds of people and their very different worlds came together in that beautiful green valley where we were living. In many ways I felt like an outsider there (I’ve felt that pretty much everywhere I’ve lived, honestly), and yet there was also something familiar, and comforting, about that semi-rural landscape. I think the character of Joan was born of that familiarity and comfort, and her relationship with Richard echoes feelings of my own through the years, connected with being a kind of rural/small-town person in the midst of “city folks”—people whose taste and sophistication were things I sort of feared, but also longed for.

One of the things I love to do, in writing fiction, is create a place through the eyes of an outside observer like myself (so, south Florida through the eyes of German tourist Inge in “Everglades City,” and tourist sites in Greece and Rome through the eyes of both young and older Fran in “The Beauty of Their Youth”). I like depicting details of setting—like the alligator-handler show in “Everglades City,” or the remote mountain church on the Greek island of Naxos in “The Beauty of Their Youth”—through a visitor/outsider’s eyes. But I also like depicting that outsider character’s longing, and inevitable failure, to truly know and understand “the locals” in these places. That longing, and that acknowledged failure, are absolutely my own.

I’m glad you’ve started with this question, Kate, because—as you know, having just finished your most recent book, Tuesday Mooney Talks to Ghosts (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), I’m eager to hear about the decision to make your beloved Boston the setting for that novel’s quest story. I’m curious whether you consider yourself a Boston “insider” or “outsider”—or maybe somehow both? Especially now that you’ve moved away. And I wonder, too, if leaving Boston made you want to write about it in the way that you do in Tuesday Mooney—a way that I can only describe as steeped in deep affection. I won’t soon forget the scene of Tuesday riding the T and, even in a statement of bewilderment and despair, watching her city go by outside the window with such tender and loving attention.

I would’ve said, once, I was an insider-outsider in Boston, which is sort of the classic Boston experience; there are plenty of locals, but it’s also a city of transplants, people who come for school or work, which creates its own kind of insider-outsider community.

I left Boston in 2014, so I’m definitely an outsider now when I go back to visit. The neighborhoods I’ve lived in are gentrifying, some of the restaurants I ordered weekly takeout from are closed. But I have so very many memories, and the Boston on the page in Tuesday Mooney is my own. I had to leave it, had to get a little more distance, to see it with any clarity, even as my view of Boston is deeply sentimental; it’s a view of a place fueled by great affection and gratitude for the life I made there, and grief for missing it. That, I think, was where the novel began—a desire to travel back to my Boston and spend some time there, recreating it on the page and sorting out what the previous 11 years meant to me.

What comes first for you when you’re writing a story? The setting, the characters, or a question that feels as though it can only be tackled through fiction?

For a long time I would have said setting; certainly that’s the case for two of the earlier stories in the collection, “Everglades City” and “Polymorphous.” For “The Beauty of Their Youth,” it was a combination of setting and character—in this case the characters of the sisters, Valeria and Carlotta, who own and run the Hotel Cinecittá. They were loosely based on two women I observed over the few days I stayed in a hotel in Rome back in 2012.

But it was definitely “a question that feels as though it can only be tackled through fiction” that prompted both “A Better Law of Gravity” and “Benedicta, Or a Guide to the Artist’s Resumé.” In the former, that was simply the question of what might have happened, a few years later, to a sad adolescent girl like Frankie in Carson McCullers’s A Member of the Wedding. In the latter, I remember that I started out with just a kind of vague curiosity about the genre of the artist’s resumé, and the thought that surely certain artists had chafed against the autobiographical focus of a number of artists’ resumés that I’d read through the years at gallery shows, etc. The character of the Painter Van Lloyd was born, at least in part, from that question: what if an artist doesn’t particularly want to peruse—and share—his personal past in an effort to chronicle and somehow explain his art? (And I use the masculine pronoun here deliberately, because there’s a certain reckoning with his own sexism that happens when the Painter Van Lloyd tries to construct a resumé in this way; how successful that reckoning is is open to question!)

To turn this question back to you (and speaking of—maybe—chafing against the expectation to share autobiographical detail!): I was so intrigued by Tuesday’s line of work in the novel, and also by your very interesting take on extreme wealth—who has it and what they choose to do with it. I think your book is such a quietly powerful critique of late capitalism, Kate, which is one of the things I just loved about reading it. Of course I did wonder, as I read, to what extent you were drawing on actual experiences during your time as a development researcher; I wondered in particular about your feelings about the fact that so many of the details of our lives (like our net worth—and also our various surgeries!) are actually publicly available.

I’m so glad you enjoyed that element! Tuesday Mooney is a love letter to my eleven years in Boston, and a reckoning with the full-time jobs I held while I was writing my first two novels on weekends: first as a marketing writer in institutional finance, then as a prospect researcher, compiling dossiers on wealthy donors, in fundraising. The implicit critique of wealth disparity and extreme financial (and social) privilege is absolutely intentional; as much as the novel is a comedy about a treasure hunt, and figuring out your life while you’re well into living it, it’s suffused with my own indignation about just how grossly out of whack—money, power, care and responsibility for other people and the planet—modern life is under late stage capitalism. It doesn’t have to be this way, either, which smacked me in the face when I was researching and profiling the wealthy professionally: the problem, as such, isn’t that we don’t have the literal or figurative capital to solve the complex issues that face humanity, it’s that we don’t, as a culture, have the will. Yet. Which can sound bleak—and I’m not saying it isn’t—but wills can change, with imagination and intention, education and action.

Being exposed to the details of those financially insulated lives, the stock transactions and property records and foundation tax filings, was a wake-up call for me (and enormously interesting, what can I say; I’m nosy), and it honestly doesn’t bother me too much that that information is discoverable. I’d rather have facts about money transparently available, and for people to have access to financial reality. When it comes to privacy, I’m much more concerned about and cognizant of the data I give away simply by living digitally: my online behaviors that corporations collect and analyze for their own financial purposes, which is an insidious, hidden-in-plain-sight engine of capitalistic waste.

“Seeking balance” can sound like a buzzword these days, a cute way of naming the stress reaction we’re all having under the tremendous imbalances of modern life. And yet! Have humans ever achieved balance? (Is acknowledging balance as a goal to strive for as good as we’ve ever gotten?) As a full-time professor of writing, how do you balance your own work with the work you do in (and outside of) the classroom?

You know me well enough, Kate, to know that I feel like I never get the balance between teaching and writing right. It’s just an ongoing struggle for me, but I try to remember Grace Paley’s contention that this is an “interesting” struggle—one I’m honestly lucky to have (and I’m so aware of this, in an era of an ever-shrinking academic job market and exploitation of contingent faculty).

Very few writers manage to avoid this struggle with the demands of making a living while also trying to clear the time and the mental and emotional space for writing. You’ve had your own struggles with this, I know; how do you cope with those inevitable times of doubt, or exhaustion, or both?

It really is an interesting struggle, and one that I’m also enormously lucky to have. But there are always weird doldrums; either the topic or the simple act of writing doesn’t feel necessary or good. The best way I’m able to manage those times, as much as they probably should be managed (I’m increasingly convinced that fallow periods are crucial to the process, like mandatory rest), is through structure and action. I structure my weeks (and my budget) with part-time jobs, volunteer commitments, freelance and teaching assignments, so that they’re not interminable periods of “well, you could/should be writing” stress, but defined and discrete. I try to remind myself that the writing itself is the thing, its own reason and its own reward; it doesn’t have to be or mean anything other than what it means at the moment that I’m doing it. Frequently those times of extreme doubt come from worrying about everything that happens long, long after the writing happens: Will someone like this? Will someone read this? Will someone buy this? Terribly stressful questions that inevitably poison the meditative practice of writing itself, which, it turns out, is the best, healthiest way for me to think about the work.

And: I like to travel! Whether it’s a quick trip into New York to visit friends or a longer stay somewhere I’ve never been, getting outside of my routines and my own head always helps.

To that end, tourism—the frisson of being strange in a new place (or an old place, as freshly seen through someone else’s eyes)—is a recurrent theme in the collection. What is it about tourism that intrigues you as a writer?

I have loved travel, and also felt troubled by my love of travel, for a long time now. Troubled by it for reasons that are connected with Fran’s daughter Miranda’s telling her mother that study-abroad, even in a “rain forest ecology program in Mexico,” would feel like “like plopping her big, American-hiking-boot-shod foot down in the middle of a fragile eco-system.” As a traveler, particularly abroad, I go back and forth between feeling like well, at least I’m contributing to the local economy, and then feeling like the ultimate privileged imperialist. I also feel incredibly guilty when someone else has to make me breakfast and clean my room; I always have. You can see all these feelings throughout “The Beauty of Their Youth” and also, to some degree, in “Everglades City.”

And yet I also share many of Fran’s delights and enthusiasms about ancient Greek structures and Roman fountains, and—unlike Fran—I also love old churches. The Florida Everglades fascinated me, ecologically certainly, but also sociologically. I love sitting in public places—a park, a library courtyard, a café or restaurant—in a place that’s far from home. I even love doing that at home, by myself, with no one I know nearby. These tend to be the moments that set my mind going with story ideas.

I guess it’s that writer as outside observer thing again. Mostly—when I’m rested, when I’m not giving in to the pressures of work or the distractions of the internet or some combination of these things—I’m at my best, writing-wise, when I do not feel at home. Traveling/tourism is probably the best way to make that happen. But I can feel like an absolute stranger in the Indiana town where I lived for the first eighteen years of my life, and even in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where I’ve now lived for going on eighteen years. And it’s that sense of beautiful strangeness that I think I’m always looking for. Even when it feels sad to me—when, for instance, I return to Evanston, Illinois, where I lived for two years in the mid-eighties, and discover that the house where I lived in an attic apartment is simply gone. Clearly torn down at some point (which wasn’t all that surprising; it was already on the verge of falling down when I lived there). Or when I drive through that Indiana town where my brothers and I grew up and discover that our house is now covered in brand new siding, with a new shed and a trampoline in the backyard.

How do you feel, now, when you go back to Boston? Or to upstate New York? And does traveling energize you for writing, or does it maybe have the opposite effect? (I’ve definitely taken trips that have left me kind of flattened and uninspired too.)

Traveling typically does energize me for writing, for practical reasons: anytime I’m in a car or a plane or a bus, listening to music, daydreaming, I always get some good thinking done, the part of the writing that isn’t putting words together in sentences but is equally important. Sometimes I’ll get my thinking done while I’m writing, but more often than not the big ideas come when I’m doing something else. Plus, while I’m traveling, I’m usually not writing, so it creates a bit of an absence-making-the-heart-grow-fonder situation.

I definitely have that same experience you describe, the inspiration of beautiful strangeness—when I go back to my hometown of Syracuse or Boston, it’s as if everything is double exposed, or my memories start to feel like they may have been dreams. Was that strip mall always there? Didn’t that restaurant used to have a blue sign? But there’s always some recognizable feeling, like the place I knew is still singing the same song, even if it’s progressed to the next movement in the symphony. I love that dislocation, too, even if it’s sad (ha! especially if it’s sad). Sometimes it’s disarming, but it’s also a little like proof of time travel: to have known a place long enough to remember its previous lives.

The stories in Beauty of their Youth capture that slipperiness beautifully, of fumbling to grasp something once or almost known. In several of the stories, characters act without being able to name their own motives: FJ gets in the car with her sister-in-law Janice even though she knows something is amiss, and German tourist Inge purchases firearms in Florida without owning why she’s compelled to do so. What do you think makes fiction—and the short story in particular—a useful way of investigating understanding itself, and the tension between what we do and why we do it?

I think of fiction—and the short story in particular—as one place that doesn’t try to explain everything about our behaviors and decisions actually. I read a review of a novel from a few years ago recently that was positive overall, but near the end basically took the author to task for having inserted a whole, long backstory for one of her characters that seemed to be designed to explain everything about this character’s later life and actions. Basically, this reviewer seemed to feel that that inserted explanation diminished the novel’s power considerably, because it removed (or tried to remove) the fundamental mysteries that lie at the heart of all of us as humans. I haven’t read the novel (I still might, disappointing review or not, because I’m curious about it), but that particular critique really resonated for me.

We make so many choices without really knowing why—and our backgrounds, I think, can only go so far in explaining our present lives. I’m aware of struggling, in my much of my writing, with the need for a story or novel to end in a way that feels satisfying—that leaves readers feeling that they understand characters more fully, whether those characters understand themselves or not—and a concomitant need for what I see as necessary ambiguity. For characters to remain, fundamentally, opaque, at least in certain ways. The world I live in certainly feels that way—mysterious, unaccountable, ultimately not fully knowable. That’s why it’s still interesting to live here.