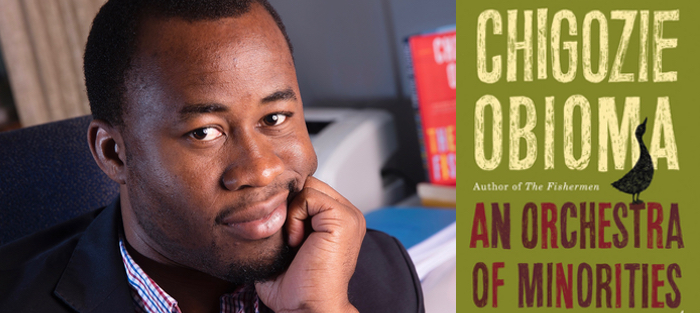

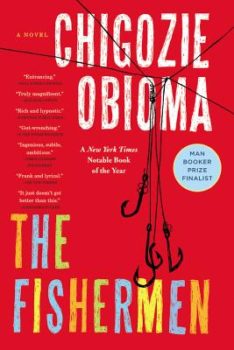

Chigozie Obioma’s second novel, An Orchestra of Minorities (Little, Brown and Company), is a sweeping odyssey in which the protagonist Chinonso finds love, loses it, and then tragically tries to win love back again. Told from the perspective of Chinonso’s 700-year-old chi, or spirit in the Igbo tradition, the novel dives deep into magical realist fiction, where human characters commit actions with cosmic implications to which they are often unaware. For this reason, Obioma’s new novel is distinctly different from his award-winning debut, The Fishermen, a novel that explored brotherhood in Nigeria, and which was grounded in realism rather than the fantastical. Still, fans of Obioma will be delighted to find in this new novel the same brooding questions of innocence and suffering, fate and agency, and the paradoxical capabilities of the human condition: that we are sublime in the throes of love just as we are capable of the darkest crimes.

With beautiful, immersive styling, An Orchestra of Minorities asks much of the reader: how far are we to go for love, and when does love cease to become love and morph, rather, into something disordered and tragic?

Interview:

Aaron Brown: Could you describe working on a novel so heavily steeped in Igbo tradition while you were living in the American Midwest and traveling to promote your first novel? How did you immerse yourself back into the culture of your homeland?

Chigozie Obioma: While I love the US for many reasons, it is the conditions of inadequacies in Nigeria that displaced me and made me an exile in America. I wish that Nigeria could provide me with what I need to thrive, and I’d be living there permanently rather than splitting my time between here and there. There’s no place like home, as they say. So, I have been thinking of these things for as long as I have been in existence, as well as the questions of Igbo cosmology and philosophy, which populate An Orchestra of Minorities.

Can you describe your process of discovering the voice of the chi narrator? Why do you feel that the book had to be written from this perspective, rather than, say, your protagonist’s point of view?

I have always been drawn to unorthodox narrative techniques. Even though the narrator of The Fishermen is first-person, the mode itself is somewhat unique to the character. He narrates the story by equating things—phenomena and situations—to animals and various objects he better understands. Here, in Orchestra, I wanted to explore the fundamental axiom of the Igbo ontology and belief system which is, in essence, a belief in radical duality. This worldview is encoded in the dictum: Egbe belu, ugo ebelu (Where one thing lies, another will lie beside it). The chi is at the center of this worldview in that it is the spirit double of every individual, existing in the metaphysical sphere. If there must be a duality of everything, then there must be a dual version of our reality—the terrestrial, physical. That opposite reality is the spiritual plane in which lies the chi.

I have always been drawn to unorthodox narrative techniques. Even though the narrator of The Fishermen is first-person, the mode itself is somewhat unique to the character. He narrates the story by equating things—phenomena and situations—to animals and various objects he better understands. Here, in Orchestra, I wanted to explore the fundamental axiom of the Igbo ontology and belief system which is, in essence, a belief in radical duality. This worldview is encoded in the dictum: Egbe belu, ugo ebelu (Where one thing lies, another will lie beside it). The chi is at the center of this worldview in that it is the spirit double of every individual, existing in the metaphysical sphere. If there must be a duality of everything, then there must be a dual version of our reality—the terrestrial, physical. That opposite reality is the spiritual plane in which lies the chi.

It is a fascinating and rather complex worldview and I wanted to situate a story in that reality, and thereby write for the Igbo people something approximating Paradise Lost, in which a principle, free will, is explored through a story. For me, my focus here is the Igbo dual belief in predestination and determinism all which come to being in the person of the chi, which helps an individual navigate his path through life.

Lastly, I also wanted to chronicle the landmarks of Igbo history and civilization which includes, amongst other things, the encounter with the Portuguese in the 15th century, the transatlantic slave trade, colonial rule and formation of the nation state of Nigeria, and the Nigerian civil war (also known as Biafra War). Thus, the chi is a 700-year-old narrator who is able to go back in time at every given moment to prop up instances from when it ensouled other hosts in order to give its current host advice on various things. This also meant that I was able to blend the first and second-person point of view by having the chi as the narrator.

In the twenty-first century, do you think that we shut ourselves off from the spiritual? How was writing a book about spirit narrators, fate, and ancestry meaningful to you in this day and age?

In as much as we can still write about belief systems, which often are spiritual or psychic, we can write a novel about the spirit world and these metaphysical subjects. Also, I see myself as an ontologist—one who is primarily interested in the metaphysics of being and existence. Thus, I’m often plumbing territories that are often not much discussed in fiction: fate, destiny, predestination, and the sublime.

Your choice of the chi narrator is also risky because it is unconventional. Do you worry that writers sometimes aren’t taking enough risks? Is that a problem that has resulted from MFA programs or the market and readership, etc.?

I think there has been a retreat from the metaphysical, for the most part. But I think people are writing inventive fiction—fiction that pushes the borders of what we can understand as individuals, and that reinstructs us on how to understand life and its complexities. I’m thinking for instance of Lincoln in the Bardo, which many have said is similar to Orchestra, The Luminaries, by Eleanor Catton, and Satin Island, by Tom McCarthy, amongst others. But you’re right in saying that there seems to be a limitation, and it is increasing. Modern politics in the west might be putting a lot of shackles around what can be written about, and by whom. Sensitivity can be dangerous for the arts, and can result in damaging homogeneity even though I sympathize with some of the motivations behind various movements.

This book is also about loneliness. The chi narrator frequently laments that the protagonist suffers from “despair [that] is the disease of the soul.” Later, he observes that “loneliness is the violent dog that barks interminably through the long night of grief.” I want to say that love is the cure for loneliness, but judging by the outcome of the novel, I’m not so sure. What do you think?

[Laughter.] I tend to think you’re right there. Love can be a viable panacea for loneliness. Indeed, finding Ndali brings great shine to Chinonso’s life, though that shine soon fades when he—it has to be stressed—instigates that the relationship be taken further. I don’t think it is love that destroys him. She opposes his traveling to Cyprus, but it is he who makes this choice, and the consequences are his. The novel was inspired in part by a true story, and in that story and many comparable situations, those who end up making such journeys are often doing so out of gullibility borne from desperation. Chinonso becomes desperate and makes extreme decisions. And the reason he does is because he is too afraid to be lonely again. To him, it’s like death.

And we can’t ignore the social commentary occurring in Orchestra. In the book, we see how classism divides lovers and how Europe in the imagination of men like Chinonso is often a false and perilous dream, leading one to sacrifice everything with the hopes for a better life. What are some of your goals as a writer when addressing social concerns?

You just divined rightly that there is a critique of the classism in Nigerian society. My focus first of all when I write any fiction is often the larger story, then the characters in the story, and then philosophical framework around it. Other things simply fall into place as a consequence of directing my focus on these key elements of the story. When you are gazing from a distance at a hill directly in front of you, if your sight is good enough, you will see other things too. So, those other things are usually other social concerns many of which you will find my new novel including race, revenge, immigration amongst others.

The title of the book, An Orchestra of Minorities, comes up in conversation several times in the course of the novel, a phrase Chinonso’s father used to describe the wailing of chickens when one is taken from their midst. Later, the chi observes that Chinonso is part of the “minorities of this world whose only recourse was to join this universal orchestra in which all there was to do was cry and wail.” Can you speak more about the title and this concept of collective solidarity and suffering?

One of the most fascinating things I often witnessed as a child was the sight of a hawk or kite attacking a hen and its chicks. It is often very violent, yet interesting in the sense that the hawk invests so much in precision that when it strikes, it hardly ever misses. In the aftermath of the strikes, often, what happens is that the chickens scurry about and cry helplessly. It’s that elegiac sound that is loosely translated as “an orchestra of minorities.” For me, I’ve often seen it as a metaphor for the larger society in which there are multiple players and forces that contend against each other and in which the stronger—herein, say, the rich, the privileged, the abler—prevail. In Nigeria, a rich person can ask the police to arrest his neighbor who is poor based on a provocation and that poor person can languish in jail for no reason. This results in the orchestra of minorities reaction. When a child is doing homework and suddenly a bullet from some drive-by shooting nearby hits her, that’s an orchestra of minorities. It is the brutality of fate, and it is the regeneration of life in the aftermath of tragic events.

One of the most fascinating things I often witnessed as a child was the sight of a hawk or kite attacking a hen and its chicks. It is often very violent, yet interesting in the sense that the hawk invests so much in precision that when it strikes, it hardly ever misses. In the aftermath of the strikes, often, what happens is that the chickens scurry about and cry helplessly. It’s that elegiac sound that is loosely translated as “an orchestra of minorities.” For me, I’ve often seen it as a metaphor for the larger society in which there are multiple players and forces that contend against each other and in which the stronger—herein, say, the rich, the privileged, the abler—prevail. In Nigeria, a rich person can ask the police to arrest his neighbor who is poor based on a provocation and that poor person can languish in jail for no reason. This results in the orchestra of minorities reaction. When a child is doing homework and suddenly a bullet from some drive-by shooting nearby hits her, that’s an orchestra of minorities. It is the brutality of fate, and it is the regeneration of life in the aftermath of tragic events.

Orchestra is, in some sense, a novel of a character on trial. As the chi narrator defends Chinonso to a council of the gods, did you find yourself taking one side or the other?

I tried not to, as I wanted to explore the Igbo question of destiny, fate, determinism, and effort. I wanted also to have this play out in the metaphysical milieu of an afterlife transmigration of the chi—a person’s incorporeal double—into the testimonial court of the supreme deity, Chukwu. This also gives me a lot of technical advantage to explore what I wanted to do—which is to have the chi chronicle the life of this man in the context of its own efforts to help its host. So, it is not only Chinonso’s story, but also the story of chi’s own existence during this period. The chi is basically trying to make a concerted argument that it is itself a good chi and not a bad one. This is one of the reasons for its loquaciousness, its needing to be expansive and broad, and the reason for the seemingly endless tangents on which it goes through the course of narrating the story.

So, An Orchestra of Minorities is an unusual novel because it is the history of an unfortunate individual from before he was born up to age thirty, I think.

In some ways, traditional concepts of masculinity are also on trial in Orchestra. Chinonso is on trial, after all, for having committed the “great crime” of harming a woman. And as a tragic character, Chinonso’s hubris is that he does not listen to his lover, Ndali, but instead tries to forge his own way to love. For this reason, we might say he is unaccepting of or even resistant to the feminine. Can you describe the way masculinity operates in this novel?

Well, this is not a western novel. So, it might be a bit unfair to treat it as such. That said, the novel is showing that there might be some errors in the way people see African cultures like the Igbo culture. When people act in ways that are unfair to others, it doesn’t matter the gender, they receive justice. In the Igbo culture especially, Ala being the supreme gendered deity, crimes against women are punished in serious ways. Hence, Chinonso’s chi’s grave fear is that his character will not be well-served by her judgement. It is afraid that if it does not tell everything, Ala and Chukwu will wreak punitive judgement on Chinonso. In some ways, the chi is making a failing case, and it seems to be increasingly aware of this because of the gravity of what Chinonso may have done, which is an abomination. In most of Igbo land, Chinonso’s actions are punishable by death. So I wanted to have the chi in this difficult situation where it had to explain and rationalize the actions of a host whose actions may be unexplainable.

Speaking of actions, the character of Jamike, at once a suspicious con man, experiences a radical transformation in the course of the novel. In my opinion, characters undergoing similar transformations are so difficult to pull off without sounding trite or fake. And this is why Dostoevsky himself suggests at the end of Crime & Punishment that the story of Raskolnikov’s redemption is a greater and more difficult story to tell, which is why he leaves it unfinished. Could you talk about the challenges of writing a character who experiences redemption?

I see your point, but in real life there are people like that—I know quite a few. In fact, most of the things that happened in this novel are figments of actual stories I have heard. For instance, I knew a guy back in Nigeria who killed someone inadvertently and became so transformed by it he turned into a priest. This was the inspiration for the later Jamike. But there is also a reversed arc: Jamike begins the novel as a conman acting out, at least it seems, in response to something that has been done to him in the past. When he learns that his actions has caused someone else’s death, he makes a complete change to his life to atone for what he had done. And the best way such atonements happen in a religious country like Nigeria is usually through religious transformation. So, Jamike starts out bad, and ends up good. Chinonso, on the other hand, starts out good, selfless, willing to give up anything to save others. But he ends up consumed with rage and resentment, tirelessly looking to revenge, to gain back his old life. I think the tragedy in this is that the later Jamike, in trying to save Chinonso, ends up destroying him when Jamike brings news that he has found Ndali. It is a string of unintended consequences throughout.

I see your point, but in real life there are people like that—I know quite a few. In fact, most of the things that happened in this novel are figments of actual stories I have heard. For instance, I knew a guy back in Nigeria who killed someone inadvertently and became so transformed by it he turned into a priest. This was the inspiration for the later Jamike. But there is also a reversed arc: Jamike begins the novel as a conman acting out, at least it seems, in response to something that has been done to him in the past. When he learns that his actions has caused someone else’s death, he makes a complete change to his life to atone for what he had done. And the best way such atonements happen in a religious country like Nigeria is usually through religious transformation. So, Jamike starts out bad, and ends up good. Chinonso, on the other hand, starts out good, selfless, willing to give up anything to save others. But he ends up consumed with rage and resentment, tirelessly looking to revenge, to gain back his old life. I think the tragedy in this is that the later Jamike, in trying to save Chinonso, ends up destroying him when Jamike brings news that he has found Ndali. It is a string of unintended consequences throughout.

While reading the book I couldn’t help but think of Ben Okri’s The Famished Road while picturing the animation of Hayao Miyazaki at the same time. In the past, you’ve referred to Amos Tutoula as an influence. Were there authors, especially ones readers may not be familiar with, who were an influence as you worked on Orchestra?

Yes, Tutuola, but there is also D.O. Fagunwa, who has been translated into English by Wole Soyinka. There are also writers who have written within a metaphysical framework like John Milton, Dante, and most recently George Saunders, even though I read him after I had submitted the manuscript for Orchestra to my publishers, I think.

Many readers in America may not realize that some of the best novels in English are being generated in countries like Nigeria and India. What will it take to make America more aware of world literature, and are there some books you have read recently that you would like to recommend?

A lot is hampering it, sadly. In today’s America, I think there are not that many individuals who are open to reading books from other cultures and coming to these books not through their own western lens but on the terms of the cultures in which those books are set. They are the ones who can read without serious ideological bias, and they are the ones who can truly appreciate that we live in a world where everybody does not think like us or act exactly the way we act. This is the essential beauty of the world.