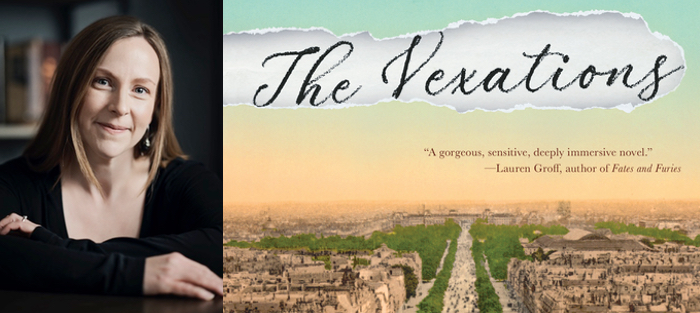

Caitlin Horrocks’ novel, The Vexations (Little, Brown and Company), follows the life of the French composer Erik Satie (1866-1925), as well as the lives of several of his friends and family members. We see Erik’s brother Conrad, his estranged sister Louise, a poet and collaborator named Philippe, and the artist’s model Suzanne Valadon. Through these alternating points of view, she explores the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Bohemian Paris art scene of Renoir and Debussy and the circumstances that cultivated Satie’s genius while stifling the musical ambitions of his sister Louise. Kirkus Reviews calls the book “finely written and deeply empathetic,” and Rachel Duboff, writing for the Los Angeles Review of Books, says that in spite of the author’s obvious understanding of classical music and French history, “What’s most extraordinary about The Vexations is the writing itself.”

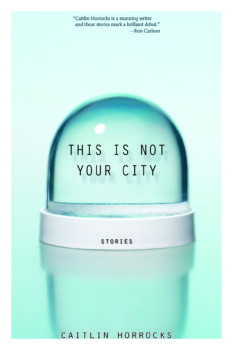

Caitlin and I met more than a decade ago as MFA students at Arizona State University, and I have admired the range and skill of her writing since then. Her short story collection, This is Not Your City, was named a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice, a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and one of the best books of the year by the San Francisco Chronicle. Her stories and essays have appeared in anthologies such as The Best American Short Stories, The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories, and The Pushcart Prize, as well as in journals such as The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The Atlantic, Tin House, One Story, and Salon. We conducted this interview by email.

Interview:

Marian Crotty: The Vexations pulls off a lot of things that are hard to do—it covers a huge time period (1872-1944); tells a story about real people; draws on historical research about art, music, and daily life in early twentieth century France; and includes multiple storylines. Did the novel feel ambitious while you were writing it? Which technical aspects proved the most challenging?

Caitlin Horrocks: The book always felt ambitious, right from the beginning. I’d been trying for a few years to get going on a novel, but all the ideas I had were story-sized ideas. Then I wrote a short story inspired by some brief research into Erik Satie; as a story, it was a mess, with way too much going on. If it was going to be anything, it was immediately clear to the workshop group that it would need to be a novel. I met the news with mingled joy and terror: “Yes! I’ve finally got a novel idea that I’m excited about!” but also “Oh geez, this is my novel project? Set in a country and a century I don’t live in, where the characters are all speaking a language I read but barely speak, and are based on historical figures that other people are already experts on?”

The most challenging aspects ended up being not so much technical concerns, but larger, vaguer fears about how much research I needed to be doing, or how faithful I ought to be to the historical record. I kept changing the characters’ names, to give myself more freedom, and then changing them back. Choosing the right moments and character interactions to stand in for huge sweeps of time was challenging, but my biggest obstacle was a sort of reoccurring anxiety about the nature of the project.

How much of the novel is based on real events? Did you have any guidelines for yourself that helped you decide what could be invented and what couldn’t?

Despite all my huffy name changes, the novel ended up being very closely based on real events. All the major life events for all of the characters follow what’s known about their lives. I often didn’t know the how or why of an event, so my imagination took over there, but I didn’t really mess with the what, when, or who.

Despite all my huffy name changes, the novel ended up being very closely based on real events. All the major life events for all of the characters follow what’s known about their lives. I often didn’t know the how or why of an event, so my imagination took over there, but I didn’t really mess with the what, when, or who.

The general rule I arrived at was that, if I knew it couldn’t have happened, I didn’t write it. I’m sure I put people in rooms together who maybe weren’t in real life, or who, when they were, didn’t say quite what I’ve got them saying. But if I knew based on the historical record that certain characters couldn’t have been in that room together, I didn’t write that scene. The research provided as many gifts as it did constraints, and even the constraints ended up feeling like part of the game. Removing them would have been, for me, like removing goalposts or side lines, leaving me wandering aimlessly around the playing field.

(One exception I’ll cop to: when the Satie children were brought to their grandmother’s house in real life, their grandfather was also alive. I tried like heck to give his fictional counterpart something meaningful to do, and every scene he was in was better without him in it. So, my apologies to Jules Satie.)

What inspired this book and what, if anything, do you wish more people knew about Erik Satie and his music?

I first played Satie’s “Gymnopédie No. 3” as a kid, and fell in love with it. I immediately wanted to learn more Satie music, assuming it would have the same melancholy beauty I loved in the Gymnopédie. Some of his pieces do. But many others are more fragmentary or experimental, more playful or comedic. Where another composer might write simple performance indications like “Allegro” (fast) or “Lento” (slow), Satie wrote ones such as, “Like a nightingale with a toothache.” As a piano student, I was more dismayed than anything. But I was curious about the person who had created this wildly diverse range of music. I held on to that question for a long time, until I was an adult and a writer.

I wanted The Vexations to be equally accessible and equally entertaining both to people who were already interested in Satie, and to readers who knew little or nothing about him, but I would love for readers in the latter camp to listen to some of his music, especially anything other than the Gymnopédies. If Satie is listening in on us from beyond the grave, I think he’s thoroughly annoyed that those three pieces are played more than the rest of his work put together.

In an interview for The Indiana Review, you spoke about two ways that research got in the way of writing—first by doing too much research before you began the novel and second by letting a minor research question stop the drafting process. I’m wondering if you could say a little more about research strategies. What types of research ended up being the most useful? What advice would you give to someone working on a historical novel?

The research came in waves: there was an initial push during which I attempted to learn absolutely everything there was to know about Erik Satie’s life and music. I read a lot of biographies and music scholarship. Knowing everything about Satie was impossible, but not nearly as impossible as what I tried to do next, which was a second wave of research focused on learning everything there was to know about daily life in France between 1872 and 1925. Then there was a third wave, once the book had come into firmer focus, of trying to track down specific information I needed about custody law or perfume production.

If I could do it again, I would give up earlier on the impossible goal of knowing everything about everything. I’d also read more contemporaneous novels and personal narratives from the beginning. The biographical and musical research wasn’t wasted, but it wasn’t what I needed once I sat down to actually write scenes between these people and realized I didn’t know what they were wearing, or whether they had running water. Books where foreigners recorded their observations about French life, whether as tourists or residents, were especially useful, especially How Paris Amuses Itself by F. Berkeley Smith (1903) and Home Life in France by Matilda Betham-Edwards (1905).

My most general advice to writers working on historical fiction is to do as I say, and not as I did, and to try to relax at least a little, and trust in both the power, and the necessity, of imagination. A quote from E.L. Doctorow that’s been meaningful to me, that I wish I’d found earlier: “The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.”

Two of the most vivid characters in the book are women whose lives are deeply impacted by sexism (Louise and Suzanne). Juxtaposing these characters’ storylines with Erik’s narrative makes the freedoms of early twentieth century bohemian Paris feel much more gendered. Were you thinking about the relationship between gender norms and the production of art when you were writing this book?

I wasn’t at first, but then came to realize that I couldn’t write the book without grappling with these issues. Satie is about as close to a solitary genius as you can get, and it’s still impossible to separate him or his work from the whole network of family and friends and financial stresses and professional pressures that make up a life, and that shape how art gets made and distributed, both then and now. Satie made sacrifices for his music, but he also had opportunities and resources that weren’t available to other people, for reasons of class or education or geography or, especially, gender.

We’ve now had a few decades of stories telling forgotten or suppressed or unrecorded narratives, highlighting women who weren’t able to tell their own stories, or whose stories weren’t considered worth telling. But I think some of those modern stories risk repeating exceptionalist clichés about the sassy princess, or the badass warrior woman. People can’t achieve anything they want through sheer gumption (although Suzanne Valadon, a self-taught painter and Erik Satie’s one known romantic interest, had about as much gumption as anyone who’s ever walked the earth); they can’t now, and they certainly couldn’t in 19th century Europe. There’s zero evidence that Satie’s sister had the ability or inclination to replicate his achievements, but she also didn’t have the same opportunities; there’s no amount of gumption that can rewrite custody or inheritance laws, for example.

I was interested in The Vexations in what happens when a character’s Life Plan A doesn’t work out, and that person has to figure out what Plan B, or C, might look like, and how to achieve contentment within that. But I never wanted the book to ignore that what A, B and C might look like were all partially defined by factors outside any one person’s control.

Before you wrote The Vexations, you published a celebrated short story collection and many subsequent stories. How did your experience as a short story writer prepare you for writing a novel? What skills were transferrable and what new skills did you learn?

Before you wrote The Vexations, you published a celebrated short story collection and many subsequent stories. How did your experience as a short story writer prepare you for writing a novel? What skills were transferrable and what new skills did you learn?

Pretty much everything transferred. I can’t think of anything short stories taught me that wasn’t useful in writing the novel, except for perhaps my over-inclination to want the individual chapters to make their own story-like arcs. A lot of them do, but I had to remind myself a few times that they certainly didn’t need to, and that it was infinitely more important that they build on each other in interesting ways. I also remember worrying that my instinct for compression would get in my way, that I just wouldn’t have enough to say about anyone or anything to fill a whole novel. But as it turned out, I was plenty long-winded. The Vexations is not a short novel, and the early drafts were even longer.

Something I thought I’d learn in this process, but I’m not sure I did, is how to structure a novel-sized plot. A lot of my plotting was sifting through sixty years of real events and deciding which scenes the reader would need or want to see dramatized, and what could happen offstage. There was a lot of selection and omission, but actually inventing a novel’s-worth of events is something I still need to learn.

In a 2011 interview with Roxane Gay, you said of novel writing, “I feel like a middle-distance runner trying to retrain for a marathon.” I imagine this feeling resonates with a lot of writers who have written short stories but haven’t yet completed a novel. What advice or encouragement can you give from the other side of the finish line?

Short stories don’t have a ton of commercial potential, but they can offer the satisfaction every few months of finishing something, sending it off, having it accepted, seeing it in print. I hadn’t realized how dependent my self-confidence as a writer was on those little boosts. I found it really, really hard to work on the same thing day in, day out, without anyone (myself included) able to tell me whether it was any good. I ended up wasting a lot of time trying to edit chapters into stories, not for the sake of the book, but because I was so antsy about not publishing anything for months or years at a time that I wanted to get pieces out the door. This wasn’t a good use of my writing time. Once I stopped cheating on the novel with shorter projects, and just settled in for the long haul, I didn’t necessarily feel more confident, but I started having more fun. The world of the novel got easier and easier to enter the more time I was spending there, and it finally started feeling like somewhere I actually wanted to be, rather than a place I dragged myself, wallowing in stress and uncertainty.

What has your work as an editor at the Kenyon Review taught you about fiction? What makes you fight for a story? What makes you pass on a story that’s skillfully done?

I passed constantly on skillfully done stories. My personal queue was chockful of previous contributors, or pieces already recommended to me by other readers, so most of the stories I passed on were skillfully done. Beyond that criterion, memorability was important to me. When I liked a story, I’d set it aside for at least a few days to see if it stuck with me. If little or nothing about it had stayed with me by the time I returned to it, I passed. That is obviously a wildly subjective test, and I always tried to be mindful of a possible selection bias towards high concept or weird stories. Sometimes stories with unusual premises can stick with the reader for that reason, and provide an easy shorthand for talking about the story with other editors. But “the love story set on the moon” needs to be every bit as good as the love story set in, say, Ohio. Making sure I wasn’t reading too quickly through quieter or more conventionally-told stories was important, and something I always tried to consciously remind myself of.

My time at Kenyon Review reinforced for me how noisy it is in a magazine’s queue, and how good work will get turned down for a variety of reasons (i.e., what if we’ve already accepted one love story in space for the upcoming issue? Are we really going to have two? Probably not.). Something else it didn’t teach me, exactly, but certainly clarified: I think every story or essay needs to contain an answer, whether implicitly or explicitly, to the question “Why does this story exist?” As a reader, I always need to feel the presence of an answer.

Almost all of the reviews of and interviews about your first book, This is Not Your City, noted your range as a writer—both in subject matter and style. Do you have any theories about what produces this diversity? What role does formal and technical experimentation play in your writing process?

I don’t know how else to write. I mean, I guess I can imagine it, but the only thing that’s going to get me to the blank page every day (or more accurately on sporadic days—I don’t write every day) is the experience of trying something new. Sometimes that’s a really deliberate effort to try something, technically, that I haven’t done before. Several stories in This Is Not Your City emerged out of self-assignments: the first story in the collection, “Zolaria,” came from an attempt to write a story with a present tense timeline that branched off into both the past and the future. The novel rotates focus between five characters, meaning it rotates between different POVs, tenses, and locations. My range, such as it is, is a product of my desire to keep trying different things, and learning from the attempt. Also, probably my desire not to find myself just writing the same story over and over.

In addition to working as a writer and editor, you teach creative writing at Grand Valley State University. What are the most common issues beginning fiction writers have with their short stories? What are two to three key concepts you want your students to take away from your fiction courses?

The most common issue I think undergraduate fiction writers have is just underestimating the amount of time and skill it takes to get an extended piece of fiction up and off the ground. I’m not saying poetry is easier (it certainly isn’t for me), but I think it’s possible to write a good poem or two nearly by accident; you can try some folds in a piece of paper and realize you’ve made an airplane that arcs nicely through the air. Trying to write a short story, let alone a novel, is by comparison like building a cargo jet. It’s bigger and heavier and has a lot of moving parts. You have to have some serious design and engineering skills just to fit everything together and get it up into the sky. Then you hopefully also have the skills to land it.

The most common issue I think undergraduate fiction writers have is just underestimating the amount of time and skill it takes to get an extended piece of fiction up and off the ground. I’m not saying poetry is easier (it certainly isn’t for me), but I think it’s possible to write a good poem or two nearly by accident; you can try some folds in a piece of paper and realize you’ve made an airplane that arcs nicely through the air. Trying to write a short story, let alone a novel, is by comparison like building a cargo jet. It’s bigger and heavier and has a lot of moving parts. You have to have some serious design and engineering skills just to fit everything together and get it up into the sky. Then you hopefully also have the skills to land it.

I teach at a university where the students are routinely taking fifteen credits plus working a lot of hours, and sometimes they can’t or don’t make the time to really see an idea through from conception to execution. Some of them underestimate the amount of both drafting and revision it’s going to take to come out the other side with a successful story. Commitment to the writing process, to their own ideas, is the single biggest thing some of them need.

Other than that, I tell my graduating students that the goal isn’t just “to get published.” It’s to publish work you’re proud of, in places you feel proud to be in, working with people you’re proud to work with and who can do things for your writing that you wouldn’t be able to do yourself. Just because you think you can place a given piece somewhere doesn’t mean you should. Think about the word “publishable”: its food equivalent is “edible,” which is a pretty low bar. Challenge yourself to write and revise your way to something that actually tastes good.