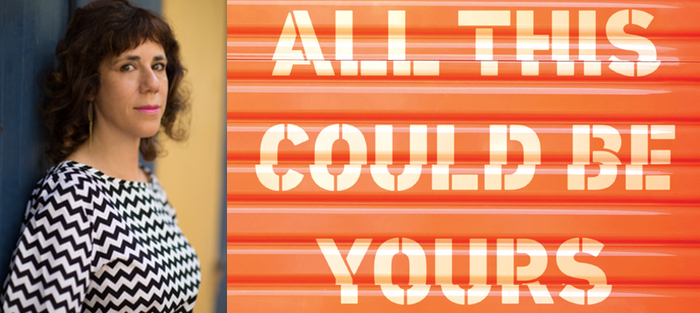

I’m waiting in a window seat in Lulabelle’s Sweet Shop on Upshur Street in Washington, DC on a rainy October morning. It’s 11 a.m. on a Sunday and author Jami Attenberg is meeting me to chat about her latest family saga, All This Could Be Yours (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). A local raises his canned Miller Lite to me through the glass in a toast as Jami rushes in from the train station; DC is just one of her many stops on a packed book tour for her seventh book. With doo-wop tunes blaring in the background and the sugared aisles of pastel lollipops beside us, Jami and I settle in to talk about the writing life, family dramas, and the insatiable and exhausting urge to tell stories.

Every family has secrets, but the story of the Tuchmans’ buried ones might soon spill if Alex, the insistent meddler, gets her way. Faced with her father’s imminent death, Alex presses for answers about Victor’s many sins. Her brother, Gary, is absent, but his wife has made it to the hospital bedside in time to have her own mental breakdown. With New Orleans as a vibrant backdrop, the Tuchmans’ matriarch, Barbra, is tight-lipped in her frustrating defense of her husband’s toxicity. Still, the family persists in exploring their dysfunction, trauma, and many regrets. All This Could Be Yours is an honest examination of whether knowing the truth ever helps anyone heal.

After our coffee, we head next door to Loyalty Bookstore where Jami is treating select readers to an exclusive boozy brunch. Hannah Oliver Depp, the owner, introduces Jami as a true “litizen” or “literary citizen,” because she’s a writer who cares for all parts of the world of words. Jami quips back that Hannah “is the future of bookselling.” It’s the perfect introduction to a book about community and the power our relationships hold in our desire for happiness.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: I’ve been thinking so much since I read your book, Jami, about whether family secrets ever protect us?

Jami Attenberg: It doesn’t necessarily matter what you do or don’t know about your family. Maybe it’s better not to know. That’s part of the relationship between Alex, the daughter, her mother, Barbra, and her sister-in-law, Twyla. They’re in this dance about what the other does or doesn’t know and trying to get the other to tell.

Sometimes secrets are interesting to know, but in the end, we’re responsible for our own actions as adults. At a certain point in life, you have to stop blaming your family and move forward.

There are so many stories about having to recalibrate. Do we have to go backward in our lives to go forward?

Alex has to figure out how to move forward. She’s going through a process. I spend a lot of time writing Alex’s thoughts. Her determination to get answers drives her, but she’s still on this emotional path that needs her attention and mine.

You write that her father’s death might be Alex’s last chance to know him: “She had given up on her parents years ago. Things would never be honest between them. So why bother with any relationship at all?” Yet, here is Alex is not giving up at all and trying to learn everything about her family’s pain all in one day.

I knew the book was always going to happen over one day. I always knew that in the drafting. It wasn’t my plan but sometimes what holds a story just shows up and you have to follow it.

Even with a one-day structure, you have all the backstory to manage.

Often we don’t talk about things in the order in which they happen. There’s a linear path to Alex’s flashback but it was still a struggle to sort. How to reveal what and when is always a challenge to manage in a book. And Gary, her brother, gets off the hook in most of the family drama because he misses his flight and is high. He chooses to check out and that leaves more burden on Alex’s shoulders. It’s not fair and yet it’s completely predictable.

Often we don’t talk about things in the order in which they happen. There’s a linear path to Alex’s flashback but it was still a struggle to sort. How to reveal what and when is always a challenge to manage in a book. And Gary, her brother, gets off the hook in most of the family drama because he misses his flight and is high. He chooses to check out and that leaves more burden on Alex’s shoulders. It’s not fair and yet it’s completely predictable.

There is an intimacy for readers generated by the novel’s structure, because we know more than the characters. For example, Alex doesn’t know everything that is happening in Gary’s life because he avoids the family but we do through the book’s telling.

That was a new approach for me. It felt risky to be so present as a narrator on the page. The authorial intrusion only happens a few times, but I felt the power of it in the story, especially in the beginning.

I don’t actually believe in closure. There are so many things we just don’t get to know. You have to take charge of your own happiness.

Happiness is just about our dogs, right?

Absolutely. They’re always happy to see us.

I’m curious about where this book began?

The book began with chapter six, Alex’s big chapter. That’s my comfort zone. I’m a character-driven writer and we’re in Alex’s head. I wanted to write about New Orleans and Alex is the first character who showed up. I saw the whole scene at once. Alex at the rooftop hotel pool and the layers of family secrets she wanted to uncover and how the rest of the family, especially Barbra, wanted to protect her husband, even at the risk of sacrificing her own identity and truth.

If the story started with chapter six, what led to the revision?

I have a lot of early draft readers and one of them wanted to hear from Victor at the beginning. I resisted but then I tried it. I didn’t want to spend time inside this toxic man’s head. I did not want Victor to lay claim to my book in any way. I don’t want to give any space to his patriarchy. I don’t even like him.

How do you write a character you don’t like?

You only give him two pages.

You’re still understanding to him, though, even when he’s horrible.

Every character gets understanding. That’s what a writer does. But abusive humans only get two pages. That’s it.

We met at the Unbound Book Festival last year in Columbia, Missouri, but we’ve mostly stayed in touch over Twitter. Can you talk a bit about how you manage social media as an author? Do you have a strategy?

We’re just writing our books, and I wish there wasn’t this intense scrutiny of our lives.

Here’s the thing about Twitter, I’m the same person in real life as I am online. I have a finite amount of things I’m willing to talk about.

Your dog, writing, and New Orleans.

Exactly. That’s all that matters. I don’t overshare.

What New Orleans writers have you enjoyed?

I don’t read a lot set in the place I’m writing about when I’m drafting, but I loved Sarah Burns’ The Central Park Five, and Margaret Wilkerson Sexton’s The Revisioners, and Zachary Lazar’s Vengeance. Those writers know how to uncover truths.

Does fiction have to be truth?

That’s an interesting question. Barbra would say the mystery is better or that the truth is only yours and you get to tell it or not.