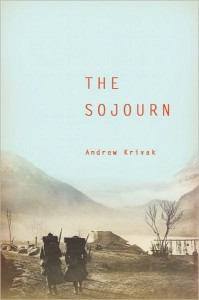

The cover of Andrew Krivak’s The Sojourn shows two men walking—their bodies close, their gaits probably synchronized—toward a mist-shrouded lake guarded by gentle green foothills. These men hail from another time, as the bulky packs on their backs attest, and at first glance they look like hikers from a century ago. But over their shoulders both men carry rifles, letting us know that they (and we with them) are not walking into a romantic natural idyll but into a war in which many lives and stories will end.

The cover of Andrew Krivak’s The Sojourn shows two men walking—their bodies close, their gaits probably synchronized—toward a mist-shrouded lake guarded by gentle green foothills. These men hail from another time, as the bulky packs on their backs attest, and at first glance they look like hikers from a century ago. But over their shoulders both men carry rifles, letting us know that they (and we with them) are not walking into a romantic natural idyll but into a war in which many lives and stories will end.

A lean and intimate tale of war and familial devastation just published by Bellevue Literary Press (which in 2010 gave us Tinkers, Paul Harding’s dark-horse Pulitzer winner), The Sojourn tells the tale of one Jozef Vinich, born in a Colorado steel town at the turn of the 20th century and destined to become a mountain sniper for the Austro-Hungarian army in World War I. Along the way he partners with various characters as he walks through a physical and spiritual wilderness: his own self-alienating father; his adoptive brother Zlee, who becomes a sniper with him; a ghost of a man, nicknamed Banquo, at a prisoner of war camp; and a pregnant Romani girl named Aishe, whose child he delivers. Despite the remoteness of his journeys—and the lives he takes along the way—he is never alone, but always graced by a connectedness to others that sustains him.

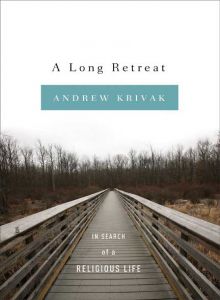

Krivak’s first full-length book, A Long Retreat (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2008), dealt with his journey toward becoming a Jesuit priest, which he gave up after eight-years to become a husband, father, and writer. In both of these books, he achieves an intimacy that neither sensationalizes, nor asks to be applauded. Instead, that intimacy comes across as part of the author’s bargain with the reader: to show the face of human life in the teeth of its own uncertainties, and in its vacillating poles of meaning. We talked about The Sojourn just as Krivak was launching his book tour.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: Most immigration stories that move from Europe to America involve leaving behind poverty and seeking better fortune. But Jozef Vinich is a native-born American citizen who spends time in Europe and returns. Why did you feel it was important for you to write a tale of that particular migration?

Andrew Krivak: This was the experience of my grandmother, her siblings, and her father. Her mother was killed by a train—the prologue of the novel comes from a true family story—and her baby brother was thrown over the trestle and rescued by boys swimming. Her father and his young family then moved back to Austria-Hungary, where he had land, a house, and could arrange to marry someone who would take care of his children. But it was a miserable life for my grandmother, and when she—at the age of 16—asked her father if she could emigrate to America in 1919, she was amazed to hear him say, “I was wondering when you would ask me. There is nothing I want more than to have you go.” Maybe to fulfill the dream he never could. I don’t know. And she loved to tell the story of how she stood in the immigrants’ line as she was getting off the boat in New York Harbor, but found herself shepherded into the citizens’ line because she had an American passport that the customs officials in Prague gave her all very matter-of-factly, without her even knowing what it was. This lore was passed down to us and it never struck me as odd, until I moved out of rural Pennsylvania, that one should grow up in country other than her own.

Andrew Krivak: This was the experience of my grandmother, her siblings, and her father. Her mother was killed by a train—the prologue of the novel comes from a true family story—and her baby brother was thrown over the trestle and rescued by boys swimming. Her father and his young family then moved back to Austria-Hungary, where he had land, a house, and could arrange to marry someone who would take care of his children. But it was a miserable life for my grandmother, and when she—at the age of 16—asked her father if she could emigrate to America in 1919, she was amazed to hear him say, “I was wondering when you would ask me. There is nothing I want more than to have you go.” Maybe to fulfill the dream he never could. I don’t know. And she loved to tell the story of how she stood in the immigrants’ line as she was getting off the boat in New York Harbor, but found herself shepherded into the citizens’ line because she had an American passport that the customs officials in Prague gave her all very matter-of-factly, without her even knowing what it was. This lore was passed down to us and it never struck me as odd, until I moved out of rural Pennsylvania, that one should grow up in country other than her own.

Over time, however, a couple of things began to dawn on me and shape the story toward an interest in this particular reversal, as it were. First, the reality that plenty of immigrants in those first few decades of the twentieth century went back, and I suspect it was often for reasons both fated and willed. For my great-grandfather, it was that combination of both, and I’ve always wondered if he might have struggled in his old age with what it was he might have become in America, if he’d been able to break free of circumstance and stay? Secondly, ever since I read Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses, I’ve wondered about this idea of coming of age in a land not one’s own. The Israelites had a powerful sense of the sojourn—the time of rest in an alien land—as a time when God taught them. And so, in the end, I wanted to sit down and write a coming of age novel in which the main protagonist “becomes” in a land that shapes him and teaches him, but is nevertheless not his own.

A clear vein of withdrawal, awakening, and return runs through your work—you’ve written a retreat and a sojourn. It’s possible to see Jozef Vinich’s sojourn as a very long silent retreat with lots of killing. In what ways did you embrace this common theme in your writing process, and in what ways did you try to separate yourself from it?

I can’t say I’ve ever thought about it in terms of how I embrace or separate myself from the theme of retreat. I can say, though, that I’m seemingly always interested in the search for the self, how we become ourselves, or how we change and grow from one moment of awareness to another. My memoir took up that theme because it was pretty much all that I was engaged with for the eight years that I lived in Catholic religious life. But The Sojourn takes up that theme by virtue of my having wanted to attempt a coming-of-age narrative, as I said, in a land and at a time that was utterly alien to me, but which shaped those who gave me life.

This past semester I was teaching The English Patient in a seminar at Boston College, and we discussed the theme of retreat in the novel, the way in which each of those characters in that bombed-out Italian villa had come to be there, with what love and loss and brokenness defined them, made them who they were, not what mask or role they’d taken up for the purposes of survival in a war. I don’t think that we as humans consider that often: how crucial rest and retreat—with an embrace of loss inherent in the need to do such a thing—is to our own self-awareness. That ongoing search for who we are and what we ought to do. The father-in-law of a friend of mine was a marine in Vietnam, and he saw this same theme that you’ve pointed out in both A Long Retreat and The Sojourn. In an email exchange he said to me, “Finding yourself is hard. Finding yourself in a war is very hard.” That should have been the epigraph to The Sojourn.

This past semester I was teaching The English Patient in a seminar at Boston College, and we discussed the theme of retreat in the novel, the way in which each of those characters in that bombed-out Italian villa had come to be there, with what love and loss and brokenness defined them, made them who they were, not what mask or role they’d taken up for the purposes of survival in a war. I don’t think that we as humans consider that often: how crucial rest and retreat—with an embrace of loss inherent in the need to do such a thing—is to our own self-awareness. That ongoing search for who we are and what we ought to do. The father-in-law of a friend of mine was a marine in Vietnam, and he saw this same theme that you’ve pointed out in both A Long Retreat and The Sojourn. In an email exchange he said to me, “Finding yourself is hard. Finding yourself in a war is very hard.” That should have been the epigraph to The Sojourn.

All authors make their own deals with reality and they vary from not only book to book, but from character to character. What bases in reality did Jozef Vinich have as opposed to his adoptive brother Zlee?

Well, I’ve given away some of the answer to this in my answer to your first question. In many ways, a great deal of the story is based in reality. When I first decided that my book after A Long Retreat would be about these grandparents of mine who were Americans with an old-country education, I thought that I’d be writing a second work of nonfiction. When I sat down to talk to my agent about it, however, she was quiet for a long time while I talked myself more and more into an unconvinced corner, until she said, “It sounds to me like you want to write a novel.” And I did; I just needed her to say that. So, then I felt I had permission to create. And what emerged in the character of Jozef Vinich is actually an amalgam of the many characters who populated the stories passed down to me from my parents and grandparents and great aunts and uncles, and all kinds of folks I grew up listening to. And they all seemed to fit, as though longing somehow for that kind of singular identity. So that kind of seamless move from the nonfictive to the fictive was an easy and interesting one for me to make. Or maybe I should say facilitate, because that’s really what seemed to be going on.

Now let me tell you a little bit about Zlee Pes. When my parents were in their seventies, I took them to Slovakia and to the village in which my mother’s parents had grown up—the same village from which my grandfather had marched off to war. I knew the way and had visited before when I was studying Russian and Slovak as a Jesuit, so it was as easy for me as buying a plane ticket. But this trip with my parents was like no other homecoming I had experienced or could even imagine. To see my mother sitting at a kitchen table in Eastern Slovakia sharing a preserved and common history with her first cousins—separated from her by an accident of opportunity and fate—in a language that, too, had been preserved on two separate continents, made me wish that I could somehow preserve all of this myself, and keep returning year after year to that place of family origin.

And yet, I would never be more than a stranger in that land, someone whose parents happened to have parents whose parents left that land for another. Somehow, this notion of the “double” came to me through that. The idea that re-connected distant family can find a closeness as loyal and profound as brotherhood itself. And on that same trip to Slovakia, I took a photograph of a great wooden door in Bratislava, and on the door were the words, Zly pes. “Beware of dog,” but literally, “Bad dog.” My mother and I both admired this door, and I told her that one day I would write a story in which I would place a character named Zlee Pes. So, there you have it. The intricate weave of what and who is real, and what is not.

The sharpshooter is an ideal character to show working his way through a spiritual dilemma. Jozef seeks in the darkness in so many ways, both metaphorical and real. The spiritual aspect of their hunting is palpable in the reading. Were Jozef and Zlee always sharpshooters for you, or did they evolve into the role?

I love that you see the spiritual element involved in the sharpshooter. Not only the searching in the darkness but the fact that to hide is a kind of sojourn itself, and that the man who excels at this has to be an ascetic in the strictest sense, sacrificing all for the ultimate gain. The answer is that they evolved into this role. My grandfather was a gunner, a boy of seventeen put behind a machine gun retrofitted to shoot bi-planes out of the sky. He no doubt surrendered quickly, when the Italians came over the top, in order to survive. But he was raised in the mountains by his shepherd father, and I knew from my research that the Germans—and thus the Austrians as well—recruited the men of the mountains and the forests for sharpshooter training. It makes sense. And truthfully, I didn’t know how to bring together the two pieces of plot that involved the coming of age in a mountain setting, and the First World War. Around what could these two facts cohere? And then it came to me, while I was reading Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer. In it, a Lance-Corporal, Kendle, is killed by a German sniper. Sassoon writes, “Kendle was half kneeling against some broken ground; I remember seeing him push his tin hat back from his forehead and then raise himself a few inches to take aim. After firing once, he looked at us with a lively smile; a second later he fell sideways. A blotchy mark showed where the bullet had hit him just above the eyes.”

Of course, I thought. My character will be a sniper. And the two pieces of plot began to fit nicely together, once I started researching the ways in which the Austrians chose and trained sharpshooters for the front. After that, too, once I began developing the inner life of Vinich the man, it was clear to me that his role as a sharpshooter, along with Zlee, rose to the level of a calling, or at least for my purposes in the narrative.

You write very lovingly and beautifully of guns in the novel. Was it an interest you had before the book, or is it one of those cases where writing your way through your subject matter turns you on to something you can learn about?

Both. Growing up in northeastern Pennsylvania in the 1970s, guns were a way of life. We had the first day of deer season off from school not because no students would be there but because none of the teachers would be there. My father hunted and my older brothers hunted, and I began that same kind of initiation, but stopped. My older brothers went off to college, and my father lost interest in hunting. I couldn’t just go and do it all on my own, so I left that aside for other things, like fishing and books. But I’ve fired plenty of weapons in my time (all except big game rifles) and don’t feel at all upset around guns. That said, there’s an entirely other world of firearms that one enters into when delving into the weapons of war, especially the First World War, where many of the men at the front really were bringing their own hunting rifles from home with them. This I knew no amount of NRA safe hunter training in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania could prepare me for, so I started my research from square one.

The best part about it was that I was living in London at the time, and so I would get on the Tube and head out to the Imperial War Museum to do everything – from looking at photos and listening to recordings, to peering down the sights of an actual Manlicher 95. There’s also not much systematic information on the Austro-Hungarian army out there. It was an army that existed almost without equal in its disparity and strangeness, which made it as weak as it was strong. Add to that the inherent secrecy of information on sharpshooters and other early forms of stealth warfare, and the research becomes a very narrow and yet focused field, which yielded some fascinating stuff.

The Sojourn has a tight, yet varied pace. Sometimes it reads like an introspective literary novel, other times like a hard-boiled war novel. What happened within (or between) drafts to help define your pace?

At first it began as a story from the past within a story of the present, and I had Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in mind, where Marlowe tells the story of his search for Kurtz to the men at anchor on the Nellie. I was very conscious of imitating that kind of novel almost exactly. But gradually, the number of people in the room listening began to dwindle, from three, to two, to a single person, and I didn’t know what to do with that other person anymore until I realized that he had no greater status than any reader who might come to the story, sit down, and listen to its conclusion. And so, while that single person didn’t disappear, he ceased to make his presence known, and the novel proceeded with that first person voice and point of view, as intimate as though old Jozef Vinich were telling the story to the reader himself.

At first it began as a story from the past within a story of the present, and I had Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in mind, where Marlowe tells the story of his search for Kurtz to the men at anchor on the Nellie. I was very conscious of imitating that kind of novel almost exactly. But gradually, the number of people in the room listening began to dwindle, from three, to two, to a single person, and I didn’t know what to do with that other person anymore until I realized that he had no greater status than any reader who might come to the story, sit down, and listen to its conclusion. And so, while that single person didn’t disappear, he ceased to make his presence known, and the novel proceeded with that first person voice and point of view, as intimate as though old Jozef Vinich were telling the story to the reader himself.

As far as pacing goes, I had hoped to make that imitate the natural ways in which anyone telling a story for an extended period of time will vary his or her pace based on memory, what one forgets as well as remembers, emotional import, and an ongoing gauge of how the listener’s holding up. One of Jozef Vinich’s explanations is that he has been blessed or cursed with being able to remember everyone or everything that has shaped him. But that can’t possibly be true, now can it? That, too, is part of the pace. At times introspective, at times moving hard, all the while calibrating the speed, details, and usefulness or uselessness of what to remember and what to forget in the telling of a story. How well that succeeds of fails in the telling, I suppose, is up to that silent reader to decide.

There’s also a circularity to the novel—it ends with Jozef bringing a child to safety, just as he was bought to safety in Pueblo, Colorado as a baby, both infants having tragically lost their mothers. How did this theme come to you?

That physical act of surrendering, the preservation of life in the face of death, is something I’d had in mind for the book since the beginning. I wondered what my great grandmother must have been feeling—believing—in order to throw her baby boy into a river just seconds before she was killed by a train. An entire strand of fate is preserved by that momentary act of will. And so I wanted to see what would become of that character, now that he had been given the opportunity to live and grow and act on his own. And I tried to keep that motif intact throughout the novel, the physical act of surrendering, right up to the point where Jozef finds himself literally delivering the Romani child from death into life. Salvation begets salvation. One of the things I wanted to resist in the novel was some great narrative arc with a big payoff at the end. I wanted, rather, to let the great arcs give way to the small acts. This seems closer to a whole other kind of truth.

That physical act of surrendering, the preservation of life in the face of death, is something I’d had in mind for the book since the beginning. I wondered what my great grandmother must have been feeling—believing—in order to throw her baby boy into a river just seconds before she was killed by a train. An entire strand of fate is preserved by that momentary act of will. And so I wanted to see what would become of that character, now that he had been given the opportunity to live and grow and act on his own. And I tried to keep that motif intact throughout the novel, the physical act of surrendering, right up to the point where Jozef finds himself literally delivering the Romani child from death into life. Salvation begets salvation. One of the things I wanted to resist in the novel was some great narrative arc with a big payoff at the end. I wanted, rather, to let the great arcs give way to the small acts. This seems closer to a whole other kind of truth.

Jozef’s retrospective voice from 1972 feels distant from the young man we follow for most of the novel, who knows English but has little chance to speak it. Yet when he’s telling the story in 1972, he’s very erudite. What do you imagine happened to him during this time, and how much of his “unwritten” life story did you envision as you built his voice?

I’ve always suspected that this would be a stumbling block for some readers, Jozef’s voice in the novel, but there are a few pieces to this puzzle offered throughout that I hope are sufficient to give the man’s late-in-life voice the reality of a speaking voice, as though he might sit down with the reader and tell The Sojourn in the space of an evening, from dusk to just after midnight. It’s in the books that his father has cherished and traveled with and from which he has read out loud to Jozef in his boyhood. Thoreau, Grant, Melville, Whitman, and the Bible. Those are explicitly mentioned in the novel, clearly books that the older man has held onto from his boyhood.

And the American-ness of the older Vinich’s voice is meant to suggest that he has, in a kind of loyalty to the unorthodox education that his father gave him, continued to read and explore not only the authors he has mentioned, but others that he no doubt discovered on his own. The linguistic soup within which my grandparents grew up, and in which they were both adept at maneuvering has never failed to impress me, especially when you consider how terrible most Americans are at it. My grandfather spoke five languages as a matter of course by the time he entered the army at the age of seventeen. And then he learned three more in the course of fighting, spending time in a POW camp, and immigrating to America. So, part of not just the voice but the landscape that I wanted to capture was that linguistic complexity, within which very simple people were forced to navigate all their lives.

I understand that your next book is another novel. Why did you decide to stick with fiction instead of alternating back to nonfiction (like many writers do), and how do you see your relationship with both genres unfolding?

The one crucial thing I discovered in writing A Long Retreat, my first book of nonfiction, was the importance of story. You know, the old Aristotelian beginning, middle, and end. Whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction, conventionally or experimentally, there is no escaping the fact of story. But to answer your question, yes, my next planned book is a novel. The truth is (no pun intended) the next two books that I have envisioned are both stories that will be better served as fiction, and so that’s where I’m going to put my creative energies. The other thing I have to confess is that I am a failed poet, and I still revel in the beauty and complexity that good old mythos allows, and which one is seemingly cautioned away from in nonfiction these days. We all know that the memoir is a construct. I would rather just go ahead and tell one goddamn lie on top of another at the service of good writing and a good story, than cleave to some false sense of an obligation to tell the truth. What does John Berryman say in the sonnets? “Listen, for poets are feigned to lie, and I / For you a liar am a thousand times.”

The one crucial thing I discovered in writing A Long Retreat, my first book of nonfiction, was the importance of story. You know, the old Aristotelian beginning, middle, and end. Whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction, conventionally or experimentally, there is no escaping the fact of story. But to answer your question, yes, my next planned book is a novel. The truth is (no pun intended) the next two books that I have envisioned are both stories that will be better served as fiction, and so that’s where I’m going to put my creative energies. The other thing I have to confess is that I am a failed poet, and I still revel in the beauty and complexity that good old mythos allows, and which one is seemingly cautioned away from in nonfiction these days. We all know that the memoir is a construct. I would rather just go ahead and tell one goddamn lie on top of another at the service of good writing and a good story, than cleave to some false sense of an obligation to tell the truth. What does John Berryman say in the sonnets? “Listen, for poets are feigned to lie, and I / For you a liar am a thousand times.”

Further Links & Resources:

– Washington, D.C. – Politics & Prose on Saturday, June 4 @ 6pm

– Manhattan – McNally Jackson on Monday, June 6 @ 7 pm

– Brooklyn – Greenlight Bookstore on Tuesday, June 7 @7:30 pm

– Cambridge, MA – Harvard Sq. Coop Bookstore on Thursday, June 23 @ 7 pm

– Dennisport, MA – Dennis Public Library on Friday, June 24 @ 2 pm