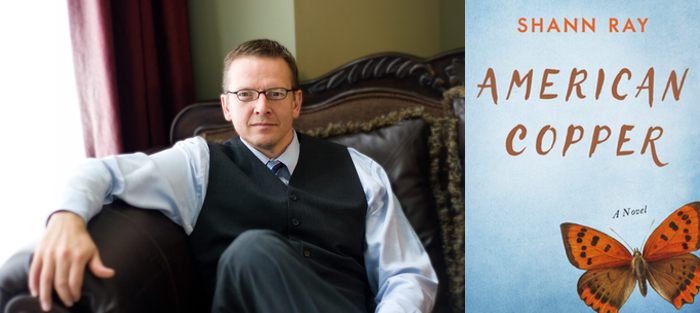

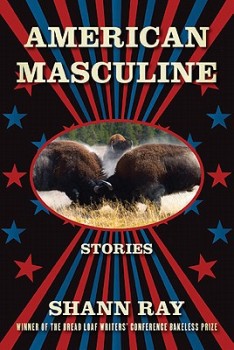

One of the things I crave most in life is the enormous. Seas or storms or mountains. Or feelings. I love it from the trailside or through the windshield, and I love it in the books I read. Five years ago, I came across a collection of stories called American Masculine (Graywolf Press), by a first-time author named Shann Ray, whose ability to conjure the largeness of life—both in the landscape that we inhabit, and in the contours of our heart’s desires—left me scrambling to find new footing in my own life. Isn’t that what the best stories have always done? Sent us back into ourselves for a closer look?

If I’ve always suspected this, I think it’s pretty much irrefutable now, after reading American Copper, Shann’s debut novel, published in November by Unbridled Books. Epic in every way, here’s a book that joins the ranks of the American West’s finest literary achievements without so much as a blush. By turns sensuous and silent and tough and tender, American Copper mines not only the rugged Montana mountains, but the seemingly impenetrable depths of the human heart cast out against the wilderness of the Treasure State.

Shann and I spent several weeks in October of 2015 writing back and forth, trying to parse our ideas on things as divergent as butterflies and rodeos. It was a pleasure to have access to such a thoughtful and wide-ranging mind. And an equal pleasure to be able to share it with you here.

PART II: To Embrace the Divine

Peter Geye: The title of this novel is derived from a couple of sources. Josef Lowry, Evelynne’s father, is a copper baron. He’s a hard, hard man, and he makes his living harvesting the earth. But he’s got a soft-spot for his daughter, to say the least. I wonder if the American Copper butterfly, the second source of the title, is in some way meant to suggest these two sides of the Baron? Are all men—hell, even all people—in some ways duplicitous?

Shann Ray: We all face our own confusing and duplicitous life, and often it breaks us and sets us out on dangerous ground. In that place, I believe we sometimes work our way toward gratitude despite or maybe because of our vulnerability. Sometimes we receive mercy or goodness from others, or the divine. Sometimes we don’t. The Baron got himself to where he couldn’t see the way ahead anymore. His own choices began to lean him continually into his darker compulsions, a path he found himself unable to diverge from. And yet there are those whose lives somehow rise from desperate beginnings into a greater intimacy. Who knows the mystery behind such things? When I read the Book of Daniel, certain lines silence me. Referring to God, Daniel says, “He gives wisdom to the wise and knowledge to the discerning. He reveals deep and hidden things. He knows what lies in the darkness and light dwells with him.” I believe there is still something to the ancient prayer, “Have mercy on me.” I doubt the possibility of God. But I also doubt the impossibility. I believe in a living hell. I’ve experienced it. I’ve seen others unable to escape it. The people who have loved me hold me in a place of hope. Heaven transcends time, in my experience, in the gaze of the beloved. I love Mary Oliver’s bright conception, “…I look upon time as no more than an idea, / and I consider eternity as another possibility.”

Is this an environmental novel? Or at least in some ways a novel about the ways in which the earth—mother earth—stands in for the absent human mothers in this book? Both Evelynne’s mother and Zion’s mother die early in their lives. Both characters are forced to navigate their lives without benefit of the feminine sensibility a mother helps to provide. Zion compensates by becoming almost one with nature. He lives much like an animal. Sleeping outside. Subsisting on very little. Wandering across Montana as if the whole of it were his home. Evelynne lives in a different kind of remoteness, mostly as a kind of prisoner in her father’s palatial home, but also in the isolation of her father’s library and in the poetry she writes. It seems that maybe both of them have chosen the lives they lead as a response to that maternal lack. Is that a fair assessment of them? How intentional was the lack of a maternal influence in their lives?

The idea that mother earth stands in for our absent human mothers is very powerful to me. I do love Zion, his inner wilderness is as vast as the wilderness around him. So he is comforted by the kinship he feels with the land and sky, the water, the stars. There is a feminine essence that speaks gently to him, and that he answers with his bodily sense of abandon. He is both strong, and willing to surrender himself if need be. At times his surrender is shrouded in desolation, and sometimes it is accompanied by joy. Evelynne too is every bit as wild as the wilderness. Like Zion, she embeds herself in wilderness, but for her it is the wilderness of people and poetry whereas for Zion it is more the rugged mountainscapes and the lonely high plains of Montana. Like each of us, they need their mothers, they need the love of a truly exceptional mother. The wilderness, in their mothers’ absence, becomes mother to them both. In the end, Zion is taken back to his mother by the scale and precipitous reach of the mountains, while Evelynne is given a reunion with others and herself in which she sees death and life as part of nature’s most unerring and tender advance. I hope the novel speaks with Evelynne’s environmentally intimate voice. The loss of the mother in the world is, for me, equal to the dominance of man over nature. In the end, the man who dominates nature, cuts off the feminine, loses his capacity to love, and, I believe, loses his will to embrace the divine… loses his will to receive the Divine embrace. Though Zion and Black Kettle walk toward very different fates, they both seek the feminine and, in the end, the feminine receives them.

The idea that mother earth stands in for our absent human mothers is very powerful to me. I do love Zion, his inner wilderness is as vast as the wilderness around him. So he is comforted by the kinship he feels with the land and sky, the water, the stars. There is a feminine essence that speaks gently to him, and that he answers with his bodily sense of abandon. He is both strong, and willing to surrender himself if need be. At times his surrender is shrouded in desolation, and sometimes it is accompanied by joy. Evelynne too is every bit as wild as the wilderness. Like Zion, she embeds herself in wilderness, but for her it is the wilderness of people and poetry whereas for Zion it is more the rugged mountainscapes and the lonely high plains of Montana. Like each of us, they need their mothers, they need the love of a truly exceptional mother. The wilderness, in their mothers’ absence, becomes mother to them both. In the end, Zion is taken back to his mother by the scale and precipitous reach of the mountains, while Evelynne is given a reunion with others and herself in which she sees death and life as part of nature’s most unerring and tender advance. I hope the novel speaks with Evelynne’s environmentally intimate voice. The loss of the mother in the world is, for me, equal to the dominance of man over nature. In the end, the man who dominates nature, cuts off the feminine, loses his capacity to love, and, I believe, loses his will to embrace the divine… loses his will to receive the Divine embrace. Though Zion and Black Kettle walk toward very different fates, they both seek the feminine and, in the end, the feminine receives them.

There’s a very complicated love triangle in American Copper. Zion is better suited at communing with horses and livestock than he is with women. Even though he’s taken with Evelynne, he can’t articulate his feelings even as they consume him. William Black Kettle is absolutely loquacious, and woos Evelynne even as she tries over and over to resist him, for all the obvious reasons. There’s an awful lot of wasted time as these three characters navigate their emotional lives. There’s much starting and stopping. And much heartache and heartbreak.

This triangle takes on an added dimension when set against the political forces working to keep love from finding its bloom. Josef Lowry does not see Zion the horseman as a proper suitor given his lowly class. And as for William Black Kettle, well, Josef becomes murderous at the mere notion of his daughter simply speaking to this man, much less becoming romantically involved with him. How important was it for you to set-up these differences of class as an aspect of their entanglement? It seems that in literature and in life, love is difficult enough without the burden of history or politics, and yet you’ve utilized these subjects to enhance the impossibility of it. Or, rather, the near impossibility of it.

I believe greed sets people on edge, and then cuts them with the same edge. That cutting is a kind of winnowing for those in the dog-eat-dog world, and also a cutting away of legitimate personhood for those who achieve the heights of greed. This progression exists for the privileged and for those who have no privilege. But I’ve experienced greater humility in the poor than the rich, and I’ve seen greater love in those with nothing than those with every convenience money can buy. My own life is full of privilege and I often fear I’ve lost the best sense of what it means to love people, the poorest or lowest among us along with the highest or most financially isolate. My privilege insulates me, keeps me from the streets, and harms my vision. I grew up in trailers and mobile homes in the small towns of Montana, and when I was closer to the ground I was faced with life’s realities every day. I couldn’t distance myself as easily. I witnessed more raw things, and more tumult. I also watched people love one another back from desperation into a hard-earned peace.

I believe class and the side effects of class directly influence our life, the mentors we are able to find, our education, and our future. A society owes all its people a fair avenue toward wisdom, autonomy, liberty, freedom, and health. When we fail to make atonement for past trauma, fail to directly pull down unfair structures, and fail to build new more equitable structures, we fail the whole human community, especially the least privileged among us. I believe the burden of history is our responsibility not only to carry but to generate answers for by following Camus’ timeless advice: “create dangerously.”

You and I have shared an editor and publisher. I remember talking to Greg Michalson eight months ago, when he was just gearing up to edit American Copper, and listening to how excited he was to bring this book to the world. It got me thinking a lot about what an enormous influence he has been on me. An influence as a writer, of course, but also as an author. I think there’s a distinction. I wonder if you’d speak some to the sway Greg has had on you and on this book. What are some of the big lessons you’ve learned from working with him?

What an editor! What a person! Greg is among the most intelligent, generous, and true-hearted people I know. He sees through the places of confusion in my work, helping us arrive through the editorial process at clarity, increased complexity, and greater mystery. Through his understanding of line and paragraph within the larger narrative, I felt liberated. I am a writer who loves smart editing. I believe in it, and welcome it. He has what we call in music, perfect pitch. His ear for what works and what doesn’t, and the way he applies his personal history of editing some of the finest writers in America (first in his twenty years as editor of the Missouri Review, then in his years as editor with Fred Ramey at MacMurray & Beck, and Blue Hen, and now with Unbridled for many years) is something I value more than he knows. His work with me is a godsend. He does what almost no one does now; he spends as many rounds with the manuscript as he feels are necessary to bring it to its most compelling form—line by line, paragraph by paragraph, and finally, the manuscript in its totality. In my experience, most editors work too fast, with little time for the necessary considerations involved in creating an essential editorial crucible. He is patient, and he applies the torque of uncommon wisdom to the manuscript, and the manuscript begins to take on the kind of uplift that is refreshing and beyond what we imagined.

I knew of his work with Debra Magpie Earling and her novel Perma Red, and Unbridled’s work with Emily St. John Mandel in the four books she’d had with them before Station Eleven. I’d admired him from afar. I trust my agent, Emily Forland, implicitly. She and I spoke of his work before he bought the book. We both hoped he’d buy it and when he did we celebrated!

What I learned from working with Greg is how clarity helps the writing transcend itself, how lyricism is beholden to clarity, and how unity below mystery creates greater artistic beauty.

What I learned from working with Greg is how clarity helps the writing transcend itself, how lyricism is beholden to clarity, and how unity below mystery creates greater artistic beauty.

Your own experience with Greg helped shape your work, I know, and now you find yourself working with Gary Fisketjon. Two of the very finest in the business, in my opinion. In our later interview for FWR, slated to appear in a few months when your novel Wintering (Knopf) comes out, we’ll delve more deeply into your experience. But for now, what is one gift you’ve received from each of them?

Greg and I have had many, many conversations about what makes fiction go. I’m talking about conversations revolving around my books, but also, and maybe just as many, about other books. Or generally about the nature of fiction. I can say without hesitation that he taught me more about the shape of a story than anyone I’ve ever known. There’s no question that those lessons have made me a much better writer. A writer who sees the possibilities of a story or a scene when I never would have even caught the scent before working and talking with Greg. I don’t even know if it’d be overstating it to say that he’s taught me more than the books I’ve read.

My experience with Gary is not as deep yet, though I hope, over the years, to continue working with him. It’s been a humbling thing, getting the chance to work with the man who has literally brought several of my favorite books to the world. I mean, he’s worked with Cormac McCarthy and Kent Haruf, Joseph Boyden and Richard Russo. I’d be lying if I didn’t say that I was intimidated when we first started exchanging notes and ideas. But here’s the thing: Gary is the most down to earth guy I’ve met in a long while, and I felt comfortable with him ten minutes into our first conversation. The reason for that comfort had something to do with his mellowness, but it had just as much to do with the absolute clarity of what he was saying. It was like hearing a perfect song. And it remains like that even now, months after finishing the edits on that book. One other thing I’ve loved about working with Gary is that he trusts the author implicitly and without question. It’s hard not to give that sort of confidence right back. There were a hundred times as I went through his manuscript notes that I thought: This man is an artist. A damn poet!

You’re a poet yourself, as well as a professor and fiction writer, and the high lyricism of the poetic line is everywhere evident in American Copper. As a writer blurring many boundaries, how conscious are you of lyric in your fiction? Is it something you strive for—the gorgeous sentence is never more than a line away in this novel—or is it a natural product of your imagination? That is, could you write any other way even if you wanted to? And I wonder also, going back to my first question, how much the landscape of your fictional world informs the language you employ? If this whole novel took place in a hospital bed or an accountant’s office could you reach the same lyrical heights?

I see myself first as a poet, though poetry remains so daunting to me I’m mostly afraid of it. Even so, poems accompany me, in memory, and in daily living. Dickinson, Eliot, Oliver, and Hopkins are part of a mutual horizon my wife and I share, for which I’m so grateful. Nothing like lyrical beauty to carry us over the divide, and to compose in us a shared music for love to flourish. Fiction is somewhat more accessible to people, but in the writing world for me poetry is first love. I love the world, and see the world’s urban sprawl, mountainous frontiers, animal life and plant life, plains both dry and fertile, and waterways riverine or oceanic as a poem written to each of us individually and written to all of us collectively. My first poetry mentor, Chris Howell (Light’s Ladder) said entire passages of Robinson (Housekeeping) and McCarthy (Blood Meridian) can stand alone as poems. I agree with him and hope to write toward that vision, holding narrative drive, character, and plot in balance with lyric capacity.

I believe the natural world, if we envision it infused with imagination, tends toward lyrical beauty even when cloaked by terror, trauma, or disaster. In Jesuit or Ignatian terms, as desolation follows consolation, consolation follows desolation. As I write this I’m in a small plane flying between England and Spain, two gorgeous countries, two empires of historical and hateful colonization, not unlike the U.S. John Newton was a slave runner. Lorca was murdered. Washington and Jefferson were slave owners. No one knows precisely what we can do with our own hateful and dominant histories, but I think we know there is something to be done, and that something must be done. In the sky above the mighty industrial complexes of London and Barcelona there is a blue and crystalline purity over a bed of white clouds that runs to the far horizon. The complex, painful, often deadly world is shrouded in the numinous. Our own healthy detachment—not being too swept away by either desolation or consolation—sustains gratitude for life throughout the continuum of our shared and immanent death. The Jesuits referred to this as, “God in all things.” The Spanish architect Gaudi said death can never be separated from God. I don’t claim to have a grasp of it, but I find the conception beautiful.

To me the landscape, natural or industrial, is charged with generative lyrical force. I absolutely love how Ondaatje reveals that force in every page (The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, Coming Through Slaughter, Anil’s Ghost, The English Patient), and it serves as a vessel for the art of loving that we experience as ever present both within and beyond the horizon of each of his books. The small towns and gigantic landscapes of Montana contain a wealth of intimacy, just as the layered streets of London or Barcelona, New York or L.A.

Last one, amigo. I always told myself that if I was ever lucky enough to publish a book, I would repay the gods by being everlastingly generous toward other writers. And certainly everlastingly thankful to readers.

You’re known as a very generous guy yourself. I wonder if you could tell me how you view your responsibilities as one of the lucky saps who gets to publish his books? Do you have advice that you regularly dole out? What are some of your favorite stories about interacting with readers?

Lucky is right. I hear you, my friend, how that braid of grace and discipline refines us. I don’t know a single writer of substance whose road to publication was easy. Every one of them worked at it, and put in the hours to be an artisan of words. Long before any books were taken for publication, my own path to placing poems and stories in the lit journals took fifteen years. After countless rejections from magazines all around the country, South Dakota Review published my first story, followed by McSweeney’s. After that, came some more years of drought, and these were difficult years. I felt hollow and emptied out. I considered whether I could really give the writing and the work what it demanded of me. I felt darkness, internally. I couldn’t go back to a life without art. And forward seemed like a desert. A renewed commitment to keep working, whether anything further was published, led the way to new, albeit precarious and painful, ground. A few years later, to my complete surprise, my collection of stories American Masculine won the Bakeless Prize from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published with Graywolf. And this was followed a few more years on with Lost Horse publishing my book of poems, Balefire, and the graceful moment when I found out Unbridled Books would be publishing American Copper.

Lucky is right. I hear you, my friend, how that braid of grace and discipline refines us. I don’t know a single writer of substance whose road to publication was easy. Every one of them worked at it, and put in the hours to be an artisan of words. Long before any books were taken for publication, my own path to placing poems and stories in the lit journals took fifteen years. After countless rejections from magazines all around the country, South Dakota Review published my first story, followed by McSweeney’s. After that, came some more years of drought, and these were difficult years. I felt hollow and emptied out. I considered whether I could really give the writing and the work what it demanded of me. I felt darkness, internally. I couldn’t go back to a life without art. And forward seemed like a desert. A renewed commitment to keep working, whether anything further was published, led the way to new, albeit precarious and painful, ground. A few years later, to my complete surprise, my collection of stories American Masculine won the Bakeless Prize from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and was published with Graywolf. And this was followed a few more years on with Lost Horse publishing my book of poems, Balefire, and the graceful moment when I found out Unbridled Books would be publishing American Copper.

I look back on those early excruciating times with an amount of heart trauma, so now I try to do all I can to encourage and affirm other writers. We need each other. Our friendships and conversations can be like oxygen, carrying us through a suffocating place back to a place where we breathe easy again.

I don’t give as much advice as I give time and consideration… I try to give friendship. Kindness from others has always sustained me. I need it now, I needed it then. I try to give what others gave me: generosity, open-hearted contact, belief in the work, belief in the person doing the work, and encouragement toward the courage and love it takes to pursue art as a life passion.

My favorite stories of interacting with readers came with the book tour for American Masculine. Two things surprised me: one, how many women the book seemed to buoy in some interior and hope-filled way, and two, how many gay men received the book with such uncommon insight and generosity. Women who had encountered the kind of tough men in that book told me stories of their own husbands and sons, fathers, grandfathers, and ex-es—men who walk the border between a warped uber-masculine and the masculine surrendering to a more humble and loving life. They spoke of the journey those men are on, the journey these women take with them. Gay men, ranging from men in their twenties to men in their seventies, approached me to speak of the stories in that collection and how the stories moved them. The conversations touched me and made me even more thankful for the long journey for that book to be published. I was struck by how art is such a healer, how truly art helps heal the heart of the world if we remain open to art’s possibilities in the soul of each person. Though it’s not for me, I respect a well-formed agnosticism, or a hard-fought atheism. And though I’m not sure what the soul is, it seems to me to be that place from which we seek something deeper and higher than ourselves, something more attuned to the collective affection, wisdom, and vitality we share, informing our daily lives with one another and leading us through our grave conflicts back to forgiveness and atonement. I think the divine comes into play whenever we cross the threshold of grace. Though the possible existence of God generates a crucible of doubt, I ask for my doubt to be changed. As the sacred text intones, “Lord, heal my unbelief.” In this hope, I believe the soul exists, even as I hope in the ancient notion that God desires intimate communion with the soul. I try to write words on my own heart in order to remember this, and also against impending darkness—words like those of Emily Dickinson, “Not knowing when the dawn will come, I open every door,” and those from Isaiah, “Arise, shine. For your light has come.”