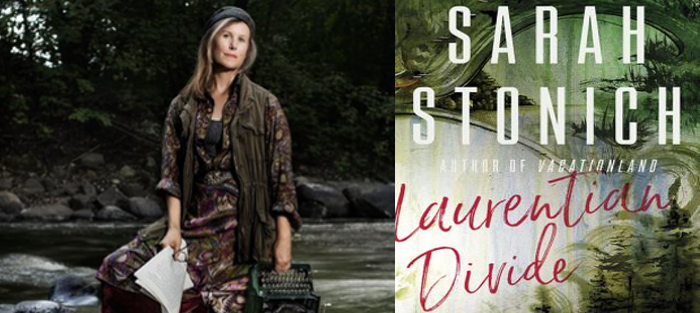

Though Sarah Stonich and I have been friends for eight or nine years, I feel I’ve known her for much longer. Back in the early aughts, I remember hearing and reading about a book set in Northern Minnesota, the only enticement I needed. I tracked the book down, and read it, and fell in love not only with the author’s great elegance, and the remarkable storytelling, but with a fierceness of virtue that I have come to think of as its author’s centrifugal force.

That book was These Granite Islands (reissued by the inestimable University of Minnesota Press). It’s a pretty amazing thing, to know someone so intimately and so profoundly before you know them at all. But isn’t that what good books do? Anyway, what I thought I knew about the author turned out to be true. In fact, has only become more true with the passing of each year of our friendship, and with each book of hers I’ve read.

Sarah is brilliant as a writer, political advocate, and a friend. Her capacity for empathy, in life and in fiction, is astounding. She’s also determined, which is no small thing unto itself. But she’s determined for the right reasons: because she thinks the world can be better for everyone. She holds both herself and the characters she writes about up to standards that could help the world improve.

Perhaps Sarah’s most distinctive quality is her generosity. This is true of her work itself, of course, but also in the ways she engages with and encourages other writers. In a world that can be cutthroat, she fosters community and respect and mutual admiration. Any one of these qualities would be enough to distinguish her from most of her colleagues. That she has all of them, and so much of each, is explanation enough for why she stands out in the vibrant community she’s so much a part of.

Interview:

Peter Geye: We’ve wandered many of the same woods up in northern Minnesota. We share an affinity for the water and wilderness. I wonder what it is about this particular part of the world that draws you to it? What particular and peculiar qualities does it possess that you find magnetic?

Sarah Stonich: Spending so much time on a specific chunk of land meant growing into my own skin almost as a moving component of the place. My physical draw to the north is probably more sentimental than I am, in the way magnets have that brief moment of resisting each other. Still, when in flux, it’s one of those places that can center me—moss, black spruce, and deep lakes are a sort of Xanax. One challenge is sheer inhospitality of the landscape—humbling reminders to curb swagger when regarding mortality.

Does your lack of sentimentality about this place give you a lens onto it that a more sentimental writer couldn’t see through? What does that lens, without the burden of sentimentality, focus on? What does it skip altogether?

Well, certainly there’s an omission of the cliché stereotype of rural Midwesterners. They aren’t all nice and folksy-yet-tight-lipped in the Garrison Keillor model. I’m compelled by what makes these characters tick, more interested in what their motivations are, and what social skills (or not) helps them thrive or fail in these small, divided communities.

Well, certainly there’s an omission of the cliché stereotype of rural Midwesterners. They aren’t all nice and folksy-yet-tight-lipped in the Garrison Keillor model. I’m compelled by what makes these characters tick, more interested in what their motivations are, and what social skills (or not) helps them thrive or fail in these small, divided communities.

A lot of us writers are one-trick ponies, but you’re decidedly not. You write with equal sureness in tones that are serious or humorous or tragic or ordinary. How do you make choices about which keys to write in? Are the choices subconscious? Do the characters themselves help you to make decisions? Do you ever tell your characters to fuck off? That you’re set on doing things your way?

Is subconscious choice really a choice? If so, I suppose that’s how I roll as a writer. Sitting back and letting characters make the decisions and allow situations to evolve naturally is probably the only arena in life where I willingly relinquish control. More often than not, it’s my characters telling me to fuck off—best for everyone when I do, leave ego and authority at the door when I sit down to write. I guess I do employ a range of keys, but the story and topic are what sets the tenor and tone.

The first book in the Northern Trilogy is called Vacationland, and it’s one of the most dynamic and inventive books of fiction I’ve ever read. I wonder if you can explain how it took shape in your mind? I also wonder if you were conceiving and planning for Laurentian Divide while you were writing Vacationland? What about the next book in the trilogy?

In Vacationland, I was creating a community and populating it with all the disparate characters in my head. At the same time, I understood that the place is a character in its own right–that every character had a relationship with the place and each other, in varying degrees of separation. In writing that book I was essentially seeding ground for the next without realizing it. I never set out to write a series, but found I wasn’t only not finished, I was just getting started. Laurentian Divide delves deeper into the lives of fewer characters. The next book, Watershed (working title), is more about how the past is so often ignored even though it almost always holds lessons for the present. But humans are human and by definition carry the curse of hubris. Watershed is about one guy looking for meaning and the tragicomic consequence of certitude. I often find myself cracking up while working on this new book. Also, the writing is starting to remind me of Phillip Roth. Should I be worried?

One of the things I find most fascinating about your writing life is how much of a chameleon you are. You wrote and published your first two novels with big, New York city publishers. Then you published a memoir with a small Minnesota press, which has since been reissued by the University of Minnesota Press, which has also published your last two novels. On top of all this, you published a fifth novel under a pseudonym (Ava Finch). Would you tell me how you view your publishing history? What have the highs and lows been? Why did you decide to publish under a pseudonym? I ask these questions because I think it could be instructive not only to aspiring writers, but also to writers weathering their own careers, even as we speak.

Wasn’t there some legendary European or Asian writer who wrote every book under a different name? Obviously, the guy wasn’t worried about brand unity or any cohesive oeuvre. Every book I write is unlike the last, and every publishing experience is as different as one Disney ride to the next. As writers we’re all at the mercy of the vagaries of publishing and bookselling, so maybe it takes a chameleon to survive it. In an order that makes no sense, I have been: a successful debut author; a struggling mid-list writer unable to get an agent; a chameleon adapting a pen name to break into another genre; and now, doing a one-eighty into screenwriting. Currently, as my fiction goes, my goal is to break out of the constraints of “regional” authorhood. Here I am on my sixth book and still really feeling like an emerging author, reaching for the larger readership beyond “flyover country,” however much I dislike that term. There’s no predictable trajectory of a writing career, and as you know it’s not easy, but if tenacious wasn’t my middle name, and if stories weren’t something that I need to wring out of myself, I’d be living happily and simply–probably as a dog trainer.

Aside from being a writer, you’re an advocate for the arts and other political organizations. How important is it for a writer to have diverse interests? How important is it for writers to be politically active? How important is a connection to a broader artistic community?

Photo Credit: Shelly Mosman

Characteristics my favorite writers have in common are curiosity, decency, and engagement. I want badly to capture the big story from above that dome containing all the small details that comprise stories. Immediately after 9-11, I was in Italy and France touring with my first novel, These Granite Islands. I was a debut author garnering seemingly unwarranted attention, until I realized that almost anywhere outside of America, writers are looked to as a sort of voice of their time and culture. In so many countries creative thought seems as integral to society as its industry and government.

So, yeah, I’m a writer with things to say. If depicting humanity as it is and writing “true” fiction from varying viewpoints can connect readers with characters that might spark empathy, why not—we could all use a whopping dose of empathy about now. Fiction shouldn’t be a soapbox, but it can be a reminder. I occasionally do a panel with other writers called “Novel Activism,” and in fact participated in one at the South Dakota Festival of Books. I do occasionally hear from readers who want to be entertained and entertained only. To them I’d say, “Sorry not sorry.”

You’ve arrived at this moment in your career in ways that aren’t entirely conventional. I hope it’s okay to say that. You didn’t go to college or get an MFA. You weren’t raised in New York or California. Your mom wasn’t a famous writer. How did you decide on this life? Are you satisfied with what your choices have brought to you? Not just professionally, but personally and artistically?

The best and maybe only way to describe my path is that I’m a “primitive,” coming to writing in a very organic fashion through reading. If I’d studied it in college (or even stayed in college) I’d surely have had the storyteller intimidated out of me in favor of a writer. Having never learned the rules or structure of fiction, I don’t even know what rules I’m breaking, so that’s a plus.

One the other hand, no academic connections means certain doors just never open—invitations to be a visiting author, or getting published or reviewed in academic publications, nominated for prizes. Que será. I didn’t choose writing so much as succumb to it.

You throw a great party. What’s your secret?

Combine the right cocktail of characters. Then give them cocktails.