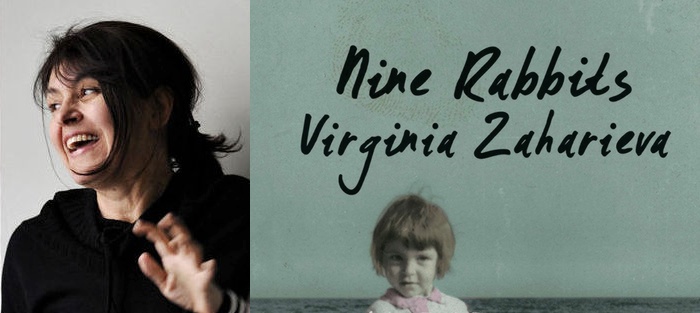

Bulgarian fiction coming into America in recent years has been a man’s club, as I noted in my recent FWR review of Albena Stambolova’s Everything Happens as it Does. Now, Black Balloon Publishing has come out with Virginia Zaharieva’s Nine Rabbits, giving us a more complex and complete portrait of fiction by Bulgarian women. Nine Rabbits is translated by Angela Rodel, who has worked with many of Bulgaria’s leading writers and been recognized for her work with grants and awards from PEN and the NEA. Originally published in the UK by Istros Books, which specializes in the literature of the Balkans, Nine Rabbits is an intense study in the barely-controlled chaos of its protagonist, Manda, at two crucial stretches of her life.

We first meet her in childhood, living on the coast of the Black Sea under the thumb of a traditional (and abusive) grandmother. The situation is hardly idyllic, as the grandmother quite literally imprints her will and rules upon Manda’s own flesh. We also follow Manda through a rough patch of her adulthood—the dissolution of her marriage (which produces one child) and her awkward, sometimes self-inflictedly painful emergence from being defined as a wife and mother to defining herself. This section, which is the larger of the two in the novel, is more convoluted, reflective, and full of emotional peaks and valleys than the part about childhood. I got the sense, in reading Nine Rabbits, not of one story unfolding before me, but of a world of stories—each of which I glimpsed a portion of as it broke the surface of its protagonist’s life before submerging itself again, only to return.

Like Stambolova’s book, Zaharieva’s unfolds in short chapters; one could even call it a novel-in-stories. But where Stambolova is cipher-like, Zaharieva is positively unruly. Her protagonist swears, drinks, doubts, curses, and fucks with the kind of inhibition appropriate to people who are going through crises. What appealed to me most about Nine Rabbits was exactly how the book handled Manda’s crises. Its careening shifts in focus and emotion, which give it great energy, stems from Zaharieva’s ability to dive into the spots of her protagonist’s psyche that are most vulnerable and uncertain. And there are quite a few spots—the book’s overall depth increases because it plumbs so many different spots beneath its surface. Zaharieva delves into body image, gender roles, Communism, careerism, Eastern spiritualities, and food—the latter of which serves as the most salient undercurrent of the novel. We get a host of Manda’s favorite recipes throughout, not gratuitously but with thematic purpose—as when a recipe for nettle soup appears in the text just after Manda’s grandmother beats her with nettles. Food serves as a connection point for the various iterations of Manda that we see, in large part because preparing food is done with the body at a level beneath language—a place where Zaharieva, as you’ll see from the interview below, is very at home.

In addition to her writing life (she is a poet as well as a fiction writer), Zaharieva is a psychotherapist whose practice combines Western and Eastern traditions; she directs the Bulgarian Institute of Body Psychotherapy. Nine Rabbits is her first book to reach American shores. In this interview, I was struck with how facile Zaharieva is in talking about the relationship between the self we call the “writer” and the self that is beyond writing—that both pre-exists and supersedes the act of putting words on the page. Even the most fanatically disciplined among us typically write for less than a third of each day. Zaharieva gives much needed attention (and implicitly asks us to give attention) to the health and unity of the self who, in those other hours, is not writing, but merely living a human life in a human body.

Interview:

Steven Wingate: Every novel makes its own deal with autobiography (and sometimes more than one). You’re a self-described grand-daughter of a gardener and a licensed practitioner of what we know in the US as somatic psychology—both traits you share with your protagonist, Manda. What kinds of deals did you strike with autobiography in Nine Rabbits?

Virginia Zaharieva : I believe in the power of the experienced story, and this book is based on autobiographical moments. My idea is to tell real stories, seek their personal meaning for me, and—by exploring the insight to which I was led—look for the universal message in them that I can share with others. Before, a good metaphor in poetry was enough for me. Now, writing prose, I take the whole narrative as a metaphor. The first part of the book is told in classic form; forty years’ distance allows me to see it as a strong metaphor. Nothing can stop life, the desire of the child to trust, to experience and to love the world.

The second part is more breathless as a text, because it requires conscious living in every moment in order to be able to see and describe life while experiencing it. The difficulty in this is to live and at the same time to transcend the meaning, to feel the metaphor. Therefore, the second part is a mix of fiction, story, document, diary, stream of consciousness, narrative by a third party—all of them shedding light on my insights of the true nature of things.

In general, both parts rely on my real experiences and reflections. But I’m looking for the distance of fiction—for meditativeness and being in the unknown—to find out things I do not know. With this book, I do try to reorder and replace, for good, some details of my own life, as I do with the appearance of Mother Efrosinia. Her role is to be a counterpoint to the brutal education methods of grandmother Nikula because, in reality, there is no one to defend the child from Nikula because the mother and father are absent. In reality Efrosinia appeared in my life when I was twenty-six years old, but she somehow absolutely naturally took her place in Manda’s childhood and supported her.

Somatic psychology focuses on the body/mind relationship in healing. Your book strikes me as using language to understand how the mind and body heal each other. Could you talk about the mind/body/language relationship and how it played into writing this novel?

Well, let’s start with the fact that it damaged my body as I wrote in bed. Writing is torture for the body; to stand still for hours is not easy. The way we see ourselves and the way we think affects our body. My yoga teacher told me that writing this book has changed my body. In the frozen blockages in our body there is a memory of primordial trauma, of buried emotions, of words and images as well. Writing is nothing but entering the memories of the body. Things start after a smell, then come the images, then come emotions, and then comes… emptiness. So writing this text I read myself through sensation. Walking back was not easy, because the body remembers the pain.

So I had a lot of fear, often ending up in places from which I didn’t know how to get back. I was feeling lost, didn’t leave the house, didn’t dress, eat. There were tears and laughter. It was good that I meditated. I wrote this book in Kovatchevitsa, a village in the heart of the Rhodope Mountains in the powerful land of Orpheus, in my garden, supported by my beloved. The aromas of the fruits and vegetables, and my cooking were also good anchor. What also helped me to convey these feelings into words were forty years of working with the language. However, this long journey started with poetry, especially in haiku form.

FWR has been very interested in covering Bulgarian literature, so our readers have seen interviews with and/or reviews of many of your contemporaries. Where do you fit with other Bulgarian writers that our readers may have met through FWR? I’m not thinking of compare/contrast so much as whose genetic makeup you feel you share.

I learned good Bulgarian language from the Bulgarian literary tradition. As my best teacher, though, I can name the poet Boris Christoff. I also learned from the Russian tradition—Gogol, Dostoevsky, Mandelstam, Tolstoy, Bulgakov, as well as the leading Anglo-American writers. I love Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, Marguerite Duras, Joan Harris, Clarissa Pinkola Estes, Sylvia Plath, Nancy Huston, Ingmar Bergman. In recent years, I’ve almost stopped reading. Only Buddhist teachings from time to time.

The original translation of Nine Rabbits was published by Istros Books in the UK. I understand you’ve added some new material for the North American version from Black Balloon. The book originally came out in 2008. What was your experience going back into it and changing it so long after you “gave birth” to it originally?

The original translation of Nine Rabbits was published by Istros Books in the UK. I understand you’ve added some new material for the North American version from Black Balloon. The book originally came out in 2008. What was your experience going back into it and changing it so long after you “gave birth” to it originally?

I am extremely grateful to the Black Balloon team, especially my editor Buzz Poole. I would describe the sensations of working with him in three words: trust, satisfaction and professionalism. For the North American version I removed a couple of texts from the Bulgarian version and I wrote two new ones. So the book became much more compact and impetuous. It was a strange experience to re-enter something finished. I made these changes while repairing a cracked thirty-foot high stone wall in my house in the Rhodope Mountains. I had to make those changes in the book while struggling with stone and a dozen tattooed ironworkers, and I wrote when I wasn’t drinking with them in the pub. Not accidentally, to this day, when I mean “house” I sometimes lapse and say “book,” and vice versa. In the physical world things require continuous care. Books and houses both need to be repaired, reinforced.

At one point, Manda writes that she participated in “the experiment called Communism,” which she refers to as “an idea that eats people.” Nine Rabbits comes out in America just a few months shy of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s fall. What role do you see Communism playing these days in Bulgaria and in the world?

Communists now are again in power in Bulgaria and the language is again replaced by lies. Again under slogans like “We care about people,” they make their dirty political moves and are only interested in power. This is depressing because we had witnessed this demagoguery for fifty years. The problem is that people are still limited within a lifeless civil disobedience. And Communists are so arrogant that they will not give up power without using violence. See what happens in Ukraine. The problem with long demagoguery is that people begin to lose the sense of truth, the sense of their own dignity and hope.

But we should not forget that when a government does not serve people, does not make and respect laws, it is immoral, and it gives a moral right to people to seek their rights with civil disobedience and violence if needed. There are two million in the Bulgarian population, mostly younger people, who live abroad and could hardly vote. In Bulgaria at the moment, we are ruled by people who are easily subject to manipulation. This is democracy gone all wrong. We are still under the heavy shadow of Communism.

Manda also writes of her fear that “if I’m not anyone’s love interest and I’m no longer of childbearing age that I’m not important to anyone.” In this, Nine Rabbits feels like a novel about the female “midlife crisis.” Is there a particular dynamic to the Bulgarian version of that crisis? In what ways is Manda typical and atypical of other Bulgarian women?

The cult of youth is typical of modern Western society. Unfortunately, Bulgaria is no exception. In our country aging is related with shame, isolation, loneliness and poverty. It takes awareness to get away from the influence of cultural and historical layers. In China, for example, it is just the opposite. They call the age after forty-five the “Second Spring” because a woman has fulfilled her social obligations. Her eyes are turned to the mountain and her vocation is to take more care of herself, balancing mind, spirit and body. She does not waste energy to produce and throw away eggs, and can take advantage of her strength, experience, and freedom in order to achieve other aspects of herself.

Sooner or later, every person faces the need to rethink herself in the context of aging and death. My character is trying to do just that—she frankly names the fears of most women at that age, but she is also seeking her solution on how to go through “second spring” with dignity, beauty and joy. The part entitled “At 46” ends with a poem for the body. Our body is the wiser tool for dealing with fears.

At the novel’s end there is a great deal of travel, and Manda opens up beyond the borders of a life that had been fairly constrained. She travels all over Europe, visits the Caribbean, practices yoga and tai chi and Zen meditation. Reading this metaphorically, I couldn’t help thinking about the process of Bulgaria opening itself up to the world after emerging from Communism. Did that play into the creation of the work for you at all?

Yes. I’m from the generation that lived thirty years under Communism, and during the subsequent twenty-five I’ve been learning how to deal with democracy and capitalism. I know what it’s like to live behind the wall and imagine the worlds beyond it. Manda is a typical representative of what we call the “Un-tied Generation.” Our passion to travel is an obsession to know, to see, and to see ourselves through the eyes of others, from which we were separated for so long.

Manda suffers from an identity crisis and a crisis of belonging as well. Moving in geography also means an interior journey in Manda’s soul. Each story and situation is a different provocation for her inner spiritual landscape, sometimes even causing an absolute immobility and difficulty in adapting. Manda’s story is an example of how the restrictions and difficulties toughen and make one’s spirit soar.

Writing is therapy for Manda—she comes out and discusses this openly. Not all writers are so enthusiastic about that idea. How do you feel, as both a writer and a therapist, about writing as a form of therapy?

I think the writer is entitled to use writing as an act of therapy for herself and for others only if she herself has gone through hell and came out on the other side. Thus the author gives the reader the opportunity to enter into the tunnel but also gives the feeling that the text is moving the reader to the light. Otherwise, if we get rid of our injuries at the reader’s expense, we risk making those readers ill, and I don’t think that is the purpose of art.

In this sense, Nine Rabbits is a healing book. It talks about the pain and suffering, but also seeks for the ways to deal with it through joy, creativity, spiritual work and courage.