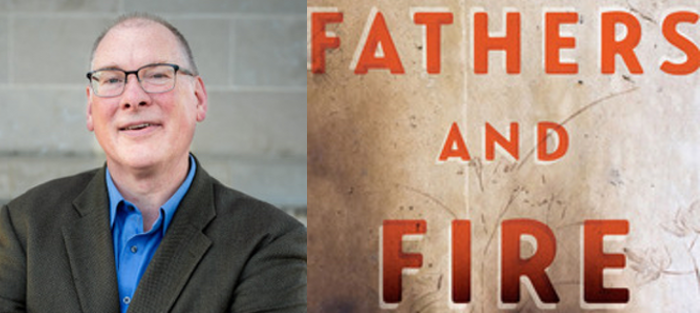

Some artists attain a mastery that spreads across fields. Steven Wingate is that sort of writer, one who will not allow himself to be fenced in by form. I met Steve at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in 2008, when he caught me rattling around like a live lobster dropped into a boiling pot. He was on the campus as a Bakeless Fellow after his collection of short stories, Wifeshopping (Houghton Mifflin, Harcourt, 2008), had been chosen for the sadly now-defunct Bread Loaf Bakeless Prize in Fiction by Amy Hempel. I revered Amy Hempel, and so had to read anyone she thought was that good, and Wife Shopping turned out to be a brilliant compilation about love, hope, and frustration, staged in the world of fiancées doubting their choices. Steve’s world thrilled me. Delightfully strange, his view stretched a little beyond physics. The collection’s Gulf Coast prize-winning story chosen by Antonya Nelson, “Beaching It,” produces a character as a literal vision in the middle of a road full of figurative choices. Here, I told myself, is a short-story master.

Maybe excellence in short forms imparts ability across the literary skill-set. Fast forward ten years, and Steve’s oeuvre has meandered into two exceptional prose-poem collections, The Birth of Trigonometry in the Bones of Olduvai (Finishing Line Press, 2013) and Thirty-One Octets: Incantations and Meditations (CW Books, 2014), and a series of fascinating, genre-bending works including an interactive romance novel, Love At Elevation, and the interactive film Talk with Your Hands Like an Ellis Island Mutt. He is what he calls himself, a genre-bending nomad.

None of that future was evident to me a decade ago when he rescued me from Bread Loaf’s lobster pot. For some reason—perhaps grounded in the same sort of empathy that permeates his writing—he sensed my displacement, and we became brothers-in-arms in that literary boil. For me, Steve brought with him the sense of calm sanctuary I find in a Catholic Masss—so perhaps our shared religious background drew us together. Maybe bourbon had as much to do with it. Maybe both of us feeling a little old to still be emerging writers. Maybe we were both a little beyond physics, caught between the real and the unreal that has always permeated Steve’s writing. That sense of existing outside material reality now especially inhabits his brilliant bildungsroman hitting the stands today, Of Fathers and Fire (The University of Nebraska Press).

Editor and author Ron Hansen snatched up Steve’s novel about a torn, otherworldly young man searching for meaning and for his father (literally and theologically) for the University of Nebraska Press’s Flyover Fiction Series. It’s a story that fits perfectly within this series, whose mission is to highlight literature of the Great Plains, the Heartland, or what the promotional writing calls “flyover country, a region more clearly defined by what it is not than by what it is.”

Perhaps that line describes the agriculture of Steve’s novel and our friendship, the search outside that boiling pot of life for what is not, more than the search for what is. This was the landscape of our interview, the flyover regions we saw in each other on the Bread Loaf Campus, and our communion on where we discovered a shared sense of mystery, of desire, of belief, and doubt. It was a delight to interview Steve and to be instructed by him once again.

Interview:

Rolf Yngve: Knowing you as I do, Steve, I was not surprised to read Of Fathers and Fire as a bildungsroman driven by Tommy’s compelling, angry struggle to find his spiritual place in the world—a struggle that is always full of risk. And I have to ask to start, where does this search for spiritual meaning fit into your personal experience?

Steven Wingate: I’m not sure what the purpose of human existence would be if not the search for spiritual meaning. The accumulation of possessions and fame is a titillating but empty alternative, and the effort doesn’t seem worthwhile since we’re all going to die. Trying to understand and reach our proper place in the network of life feels like the only worthwhile thing to be doing. We’re meant to immerse ourselves in living and pass life on to others, and everything I write concerns the human struggle to do that. Yet we put up amazing, intricate walls in the way of participating in a life that’s beneath and beyond accumulation. It’s amazing how conflicted we are about that as a species.

The bildungsroman aspect of this novel centers on Tommy first coming to terms with himself as a spiritual being, which happened for both of us at about age seventeen. He has a different experience than I did, but the phenomenon and some circumstances unite us. He and I share history, like living on the western edge of the Great Plains, loving the saxophone, and being freaked out by the incoming tide of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Our angers overlap, as well, particularly the anger of fatherlessness. Tommy never knew his father growing up, and I didn’t now mine for all that long, which can leave a hole that’s more than father-sized. It can leave you wondering why you’re here on earth. In that sense, the bildungsroman aspect of the novel explores the shared contours of the missing pieces that Tommy and I share. At seventeen, he’s realizing the same thing I did at his age: there are parts of him which might never develop fully because of the missing pieces in his life.

At the same time, I wanted to get beyond the bildungsroman and talk about America. I wanted to write about what was happening while Tommy and I were growing up, particularly the rise of the “Christian Right,” which we both got to see up close in Colorado Springs. In 1980, the Springs was the epicenter of a very aggressive kind of Christian fundamentalism that aligned itself with political conservativism and found its secular savior in Ronald Reagan. To me, this history is crucial to talk about because we seem to be living through version 2.0 of that virus, which is much more virulent than the first one.

So because of that focus, Of Fathers and Fire is a novel about Christianity. But it’s by no means a Christian novel—anybody expecting it to offer a simplistic affirmation of their faith is going to be sorely disappointed (and they won’t like the copious use of words like motherfucker, either). I wanted this book to directly engage with the right wing fundamentalist phenomenon in America because it’s an enormously important part of our recent culture and history, and it isn’t going away. Writing explicitly about religion is hardly the flavor of the month right now, especially if you’re willing to give faith the time of day. Fortunately, a few writers who talk about faith directly—Jamie Quatro, Kirstin Valdez Quade, and R.O. Kwon come to mind—have gotten some ink lately. I see Of Fathers and Fire as part of that wave, and I’m grateful to not be alone.

But Tommy is much more than simply an obnoxious youngster seeking faith, isn’t he? As I went deeper into this book, unreal or beyond-real elements began to drive the narrative for me, and my question as a reader became, what is Tommy in this world you’ve made? Where does he fit? Human and, somehow, more than human?

But Tommy is much more than simply an obnoxious youngster seeking faith, isn’t he? As I went deeper into this book, unreal or beyond-real elements began to drive the narrative for me, and my question as a reader became, what is Tommy in this world you’ve made? Where does he fit? Human and, somehow, more than human?

I love the quote “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience, we are spiritual beings having a human experience,” which is often attributed to the Jesuit priest and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Tommy fascinates me as a character because he’s just coming to understand that fact. All the things he thought he believed in—especially the machismo that made him want to be a linebacker and a U.S. Marine—are part of a mindset that puts spirituality in a box and treats it like one more thing we’re supposed to get a grip on, one more thing we’re supposed to have this false American certainty about. Tommy realizes that from another perspective, spirituality is the box that everything else in our lives fits into.

Tommy is no theologian, and he has limited tools for expressing his faith. But he fundamentally gets the idea that spirituality is the thing we live in rather than a thing we have to juggle. So to wind back around to what you say about “human” and “more than human,” I see Tommy as being more than human in exactly the same way that you and I and everybody reading this are more than human. The fact that he’s just discovering the nature of his humanity, like a toddler learning to walk, made me love him and stick with him through draft after draft. I knew he’d never figure himself out or even find a stable spiritual ground to stand on, but I went the distance with him because he had so much hunger for understanding. How can you not love a character like that?

I latched on to this sentence: “There were too many Tommies all trying to live together inside of one body, and he either had to grow big enough to fit them all in or kill some off.” I hope this isn’t a spoiler, but by the end of the book, we know that Tommy is much more than the angry, obnoxious seeker of his own soul. Talk to me about the magical aspect of Tommy or Tom-Tom. How did writing this book lead you into a place beyond our physical world?

I think we’re always living in a place beyond our physical world, and most faith traditions acknowledge that. The traditions that Western culture tends to label as primitive or ancient or indigenous are especially good at recognizing what’s beyond our concrete perception. They’re usually the traditions that see human beings as closely connected to the natural world and understand us as “spiritual beings having a human experience.”

So I don’t see myself in this novel as going off into magical realism as a stylist and latching onto that tradition. In getting to the “magical” aspect of Tommy’s spiritual life, I didn’t have to do anything but dig underneath his surface because we’re already living in the supernatural 100 percent of the time. The sense that we’re actually living another life within the one we appear to be living pervades monotheistic religions like Christianity as much as it does the more ancient ones, but it’s hidden under the surface of what we often think of as static dogma.

About those “Tommies all trying to live together inside of one body,” I have hope and fear. I like to believe he’ll be able to grow big enough to fit all of them into himself, but he’s got so much anger inside him that some Tommies might get squeezed out. I guess that’s the big question about him at the end of the novel: which parts of Tommy are going to survive the cataclysm he’s just lived through and which aren’t? How readers add that up will depend on the nature of their own cataclysms.

I think the publication of Of Fathers and Fire in the University of Nebraska Press’s Flyover Fiction Series is inspired. The novel is obviously a perfect fit owing to the setting, but what else drew you to what the press has accomplished? Tell me about the road you followed to land this book between the coasts.

This series was where I wanted to place the novel almost from the beginning, but it took a long journey to get there. I was very influenced by Ron Hansen’s novel Atticus, because of its Colorado high plains setting and its story of a father in search of his son. So the affinity was there from very early on in my novel’s conception, which was about when the Flyover Fiction series started in 2005. I saw it and thought, “That’s where this book belongs.”

Then other things happened. When Wifeshopping won the Bakeless Prize, I got my mind set on a New York publishing contract for my next book. I’d already tried and failed with the agent thing before Wifeshopping, and I failed afterwards, too. I rewrote two different novels three times each for two different agents. But I couldn’t get a sale and got tired of making edits in the name of an imaginary marketability that I felt like I’d never achieve.

So I took a break from agents—and from fiction, too. I focused on digital work (which I wrote about for FWR, recently) and pledged to let my fiction sit in its binders until I really got a bee in my bonnet and could come back with a fresh attitude. Then I got tenure at my teaching gig and asked myself what my next move was. I remember thinking, “If I die tomorrow, what one work do I want representing me?” The answer was the novel that eventually became Of Fathers and Fire, and I knew that I wanted to skip the whole agent thing and send it to the Flyover Fiction series. It got great editing, yet it stayed true to its identity—I didn’t change it to fit anybody else’s vision of what might make more money, so it feels like my novel and that means a great deal to me.

I very much admire your sense of publishing adventure and the broad approach you’ve taken toward your art. If I have this correctly, you launched your journey with an MFA in screenwriting from Florida State University, then propelled himself to out to LA to try selling screenplays. I’ve always wondered—what happened? How come you’re not running the writers’ room for the next Breaking Bad?

I wasn’t a very LA kind of guy at all, and I bombed there. I lacked the people skills to make it in Hollywood and realized that almost instantly—but hung around for two and a half years for reasons I still don’t understand. I recently wrote about my LA experience, which I really loved, for the Los Angeles Review of Books.

I was still in my infancy as a writer then, and had no idea what I was doing. I think the strongest lasting influence of my screenwriting training is in the way I approach dialogue, but I’m sure there are other influences I’m not aware of. The forms rolling around inside me all bounce off each other, and to me that’s the most fun thing about being a writer. A tool in one form can be a tool in another—they’re all interchangeable.

You’ve taken a deep swing into creating digital works over the last half-dozen years. This seems a natural outgrowth of your background in screenwriting, but can you tell me what you foresee for digital works in the context of the future for literary fiction? Or, perhaps, it might be better to call literary fiction something like, poetic story-telling.

I think books in their current form are here to stay. Every time a new art form emerges, there’s this panic that the old ones are somehow going to die. But photography didn’t kill painting, film didn’t kill theater, and interactive storytelling isn’t going to kill the novel. We simply have more forms of artistic expression, and I think that’s a good thing.

You’re dead-on in saying that my interactive run—which might have run its course, though I won’t count out going back to it—is an evolution of my background in cinema. I’ve always been interested in the way cinema interacts with other forms. I was drawn to interactivity because it allows the reader/viewer/player into the architecture of a story the way a static text can’t, but ultimately my lack of facility with technology hampered my ability to come up with quality interactive stories. In order to make the kinds of stories I wanted to make, I’d need to drop everything else and throw myself into heavy-duty computation, and I couldn’t commit to that.

But there are tons of fantastic artists out there doing things with story and code, and I was lucky enough to meet some of them while I toured around the world with my digital work. Nick Montfort, David Jhave Johnston, Emily Short, Aaron Reed, Kate Pullinger, Samantha Gordon, James Ryan, and so many more. They understand how to make pieces of code talk to each other in ways I can’t even imagine—like procedural generation of story and dialogue. (For those interested in that kind of thing, here’s an article about Ryan’s AI-generated podcast, Sheldon County.)

While I don’t think these kinds of works have produced their “masterpiece” yet, we should remember that film was around for over two decades before we even settled into a recognizable style of cinematic editing and a common sense of what a “movie” was. I think digital forms will evolve in their own line, as will traditional fiction. Will there be overlaps and hybrids? Absolutely. Does computation take away from the deep nature of the literary experience—the encounter of the self with the other that good literature delivers? Not at all.

Getting back to Of Fathers and Fire—though I’m still interested in the encounter of the self—the “flyover” setting of the novel in this tiny town of old people, Suborney, revolves on an axis of unfettered belief. Christian tropes and faith are not oddities in Suborney, but integral elements of every interaction. Compared to setting a story in, let’s say, Brooklyn or Berkeley, this town’s notion of divine presence seems integral to the water, not just the decorations on some church. Where does this come from in your experience? Where is the well for this story?

I wouldn’t characterize Suborney as a place of unfettered belief. To me it’s a place of unfettered lip-service to certain nationalistic ideas of what Christianity means—the exact kind of hypocrisy that gets Tommy riled up. With the exception of one couple who really stick their necks out for their faith, Suborney is more about the appearance of religiosity than about actual belief. One family has a cross up in their front yard for the hostages in Iran, and a little sign on it says “NUKE IRAN.” They’re engaged in a false religiosity that has nothing to do with faith and everything to do with their own sense of America’s power in the world. Their so-called Christianity is simply another version of “might makes right.”

I wouldn’t characterize Suborney as a place of unfettered belief. To me it’s a place of unfettered lip-service to certain nationalistic ideas of what Christianity means—the exact kind of hypocrisy that gets Tommy riled up. With the exception of one couple who really stick their necks out for their faith, Suborney is more about the appearance of religiosity than about actual belief. One family has a cross up in their front yard for the hostages in Iran, and a little sign on it says “NUKE IRAN.” They’re engaged in a false religiosity that has nothing to do with faith and everything to do with their own sense of America’s power in the world. Their so-called Christianity is simply another version of “might makes right.”

The “well” for this material was those teen years in Colorado Springs, where I was introduced to a fire and brimstone, you’re-all-going-to-hell species of Christianity that felt completely bizarre to me. People talked from one side of their mouths about how we have to love Jesus, and from the other side they spewed out Bible verses about punishment and vengeance. These were the people who brought us Ronald Reagan in 1980, and they helped bring us Donald Trump in 2016. One of the reasons I wanted to put out this novel now was because of the resonance between those two times.

“Lip-service in belief,” that’s what I think I was trying to reach. It makes sense. The book focuses early on the son/mother relationship, and I couldn’t help but think of a Jesus and Mary connection within the context of a bildungsroman. I thought of the Gospels’ angry young man in the temple with the money changers. But Tommy’s relationship with his mother is driven by the mystery of his father. It’s almost as if the book wants to explore Joseph, the “missing man” of the nativity. And in a larger sense, perhaps, the silence of the Father, the silence of God. Are these connections valid? Tell me about the mother/son/father relationship in the sense of this book’s spiritual viewpoint.

Part of the evolution of this novel over the drafts was from a straightforward father/son book to one that’s a mother/son book as well. This took up a lot of my effort in the later drafts, and my editor at Nebraska, Alicia Christensen, helped me darken those lines and bring it the rest of the way. Writing about fathers and sons is natural to me because I’ve got all sorts of dad issues. My biggest digital project, daddylabyrinth is all about that. Writing the mother/son story was where I stretched myself and learned new things.

The theological questions you mention are there in the base layers of the novel because it’s in part about Christianity, and also because those questions are hard to escape if you’re human and thinking about things that fall beyond the immediate self and its wants. But I don’t think Of Fathers and Fire has a particularly well-developed theology, because my goal is to stick the reader into the life of a young man who’s only beginning to realize that theological questions even exist. I’m trying to dig underneath such questions to the emotional states that allow us to apprehend them. I want to get readers into the maelstrom that is Tommy’s mind, which grasps at God aggressively but vaguely and comes up with some understandings that his mind can’t process. He’s a mess, and he’s meant to be a mess, and I love him for that mess. His theology is all over the place because he doesn’t have terms for the things he’s experiencing. He’s a child spiritually, yet this enormous vision of what the universe is has just dropped into his imagination. He’ll need some time to process things.

Along the lines of a fractured theology, for me, one element missing in this book is the word and the concept of “Christ.” The town of Suborney, Tommy, his father, his mother—all of this novel’s characters, believers, doubters, and even the disciples—speak of God, Jesus, and Mary with the sense of their ever-presence. Yet, the word “Christ” is never used. Tell me about that. What’s going on with this metaphysics?

The lack of any kind of Christ reference is Flannery O’Connor’s fault. The most important novel in my life is her Wise Blood, which I read for the first time when I was Tommy’s age. That book made me want to be a novelist, though it would be twenty years before I started trying. One of the central ideas in that novel is the “Church of Christ Without Christ,” which is the soapbox of its tortured would-be preacher protagonist, Hazel Motes.

The lack of any kind of Christ reference is Flannery O’Connor’s fault. The most important novel in my life is her Wise Blood, which I read for the first time when I was Tommy’s age. That book made me want to be a novelist, though it would be twenty years before I started trying. One of the central ideas in that novel is the “Church of Christ Without Christ,” which is the soapbox of its tortured would-be preacher protagonist, Hazel Motes.

Part of me has been trying to respond to O’Connor’s novel ever since I read it, and Of Fathers and Fire is probably the most direct response I’ll have. Tommy gets mixed up in a roll-your-own church that’s superficially like Hazel’s—and I say superficially because the people Tommy gets involved with are vastly more sincere than the ones in Wise Blood. But they’re not perfect, and they’re not immune to making all-too-human mistakes in the name of a self-interest that they confuse with spiritual self-sacrifice.

The lack of “Christ” comes in precisely because of Tommy’s naivete. He’s a babe in the woods when it comes to understanding the religion that he professes—he focuses on Jesus and Mary and tries to base his own self-made religion on them as day-to-day presences in his life. But for him there’s no endgame, no Christ bringing his spiritual experience together. That’s a gap I feel at the center of Hazel Motes’s world, and it’s at the center of Tommy’s too. They both embody that gap in dramatically different ways because they’re creatures of different times and regions, but like Hazel Motes, Tommy Sandor is a battlefield. The war going on in his spirit is analogous to the war going on in Christianity itself—one between a punishment-based faith that likes to tell people they’re going to hell and a mercy-based faith that wants us all to collectively avoid that fate.

Steve, is there an emptiness of faith in this book? Doubt, like Connie’s doubt, is very much a part of my faith. How can one have faith if one has no doubt? When Tommy’s father appears in the book, he is followed by a religious group who believe without doubt. And if one believes without doubt, then every word of the Bible can become an unassailable truth. On the other hand, if one is certain that the notion of Jesus is a sham, then the Gospels read like a version of Tommy, full of vanity and self-aggrandizement. I think faith falls somewhere in between. Where is Tommy in all this, in the end, and where are we? Are we a society, a world, a humanity with too little faith, too much certainty?

Humanity is today what we’ve always been—a species that’s way too cocky for its own good and likes to strut around acting like it knows where it’s going, even as it’s destroying everything in its path. After five-thousand years of what we call civilization, we haven’t solved the problem of greed, which is our original human addiction. It’s choking our families, our institutions (including religious ones), our nations, our planet. Solving it with laws and policies, while crucial to pursue, only goes so far because greed is a fundamentally spiritual problem rather than a legal or political one.

I personally don’t feel empty in regard to faith. Incomplete and constantly struggling for air, sure—especially as religious institutions get sucked in by the kind of sin they claim to fight—but not empty at all. Doubt is there for me, but I don’t see it as an engine in my life or in this novel. For me, the big engine is trying to align myself to the flow of a life that is spiritual in absolutely every aspect and moves in ways I can’t comprehend, but simply have to live. I guess that makes me a very Taoist-inflected Catholic.

With Tommy, though, I worry about doubt. He’s made the mistake of identifying his father with his religion, which is understandable because he’s been desperate for both a father and a greater understanding of the faith he doesn’t have words for. So he’s gotten them mixed up in a way that makes a major letdown inevitable. I don’t feel a sequel in the works for Of Fathers and Fire, but I think about Tommy beyond the scope of his book like I do with all my characters. He’s heading for a fall, for a doubt that will be hard to pull himself out of. I think he will, though I’m sure he’ll go back to being a very lost soul for quite some time. When you’ve seen and felt the kinds of things Tommy encounters, the spiritual truth inside you doesn’t just disappear—it changes shape until you’re ready to see it again.