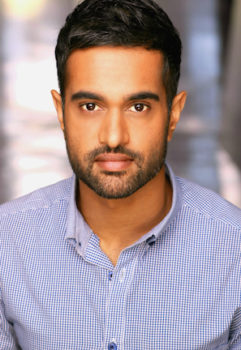

Neel Patel is deft at condensing time. Consider the first few sentences of his short story, “An Arrangement”:

I never wanted to marry Akhil. My mother found his picture on a website I had never heard of (and to which I unwittingly belonged). He was an anesthesiologist. He was a graduate of Yale. We were married in a small ceremony outside of Skokie, Illinois.

And so begins the unhappy tale of a young woman trapped in a loveless marriage, working a dead-end job, and deceiving her husband about her fertility to avoid having children. This was my first encounter with Neel’s writing. The story caught my attention precisely because of its caustic and slightly sociopathic narrator, who says of her husband, “We made love sparingly, at night usually, with Akhil on top. It was a life, I guess.” She does everything she can to push him away, and yet Neel writes with such empathy toward her.

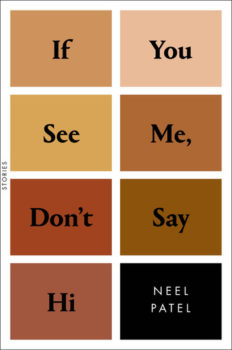

“An Arrangement” is one of eleven short stories in Neel’s debut collection, If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi. His characters struggle to break away from the confines of their parents’ homes and stifling suburbs. Issues of race and class, relationships, and sexuality deepen the complexity of the protagonists, who fall in and out of love, harm themselves and others with their recklessness, and try to define who they are outside of their families’ and communities’ expectations.

Neel was born and raised in Champaign, Illinois, to Indian parents who emigrated from Kenya and Tanzania. Several of the stories in the collection are set in the flat middle-class landscape of the Midwest and follow characters through their teenage years, as they navigate the racism of their majority-white high schools, through adulthood where they’ve often failed to live up to the standards their parents have set for them. Neel began writing in college after discovering Jhumpa Lahiri. He says, “She made writing seem possible. It was the first time I had read the work of an Indian writer writing about life in America.”

His work has appeared in The American Literary Review, Indiana Review, TSR: The Southampton Review, Hyphen Magazine, and on Nerve. If You See Me, Don’t Say Hi is due out on July 10, 2018, from Flatiron Books.

Interview:

Emily Gilbert: So tell me, what was the seed for this collection? What was the first story that came to you?

Neel Patel: Growing up, I felt othered, not only by the predominately white community in my school, but by the local Indian community, too. I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere. I didn’t see myself reflected in literature. Much of what I have read about Indians in America, though lovely and inspiring, felt like it was being told from a foreigner’s perspective. I didn’t hear myself in the words. I didn’t see my community represented anywhere.

Neel Patel: Growing up, I felt othered, not only by the predominately white community in my school, but by the local Indian community, too. I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere. I didn’t see myself reflected in literature. Much of what I have read about Indians in America, though lovely and inspiring, felt like it was being told from a foreigner’s perspective. I didn’t hear myself in the words. I didn’t see my community represented anywhere.

When I talk about “my community,” what I mean to say is the very specific generation of Indians who were born in America and raised by immigrant parents, who are both Indian and American in equal parts, and who don’t pine after a homeland far away. Many of the writers who came before me wrote about America as if it was this vast and terrifying place. I can’t imagine they grew up watching Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, or blasting rap music from their parents’ cars, or getting drunk at a high school dances. I was aware of the myth about Indians (and Asians, in general) as being nothing more than “model minorities.” When people think of us, they think of good grades and medical degrees. They don’t think of alcohol abuse and depression—which is quite common in my community, and understandably so. You can’t raise a child abroad and expect the world from him without having a few problems along the way.

The first story that came to me is, in my opinion, the most provocative: “These Things Happen.” It’s a story in which the narrator, Venkat, a troubled teenager, partakes in heavy drinking, recreational drug use, and conspires with a young woman his parents would have disapproved of. Instead of earning high marks in his classes, Venkat skips school altogether and lies about his progress to his parents. It’s subversive, disturbing at times, and a story I couldn’t resist writing.

Your characters are so aware of their behavior—even, or especially if they’re not behaving as they “should”—and I never, not once, question why they make the choices they do. I’m curious about the final two stories, “World Famous” and “Radha, Krishna.” I read them as being about expectation and the ways it shapes us.

Expectation plays a big role in this collection, and in the Indian community itself. In a way, the immigrant experience is defined by expectation. Immigrants come to America expecting certain things—the most important being success. Children of immigrants have the added pressure of knowing their success in America is an expected result of their parents’ sacrifice. If your parents said to you, “Go be whatever you want to be,” I’m sure mine, in one way or another, have said to me: “We didn’t come to this country so you could be a writer.”

The final stories, “World Famous” and “Radha, Krishna,” came to me at the eleventh hour, after the collection had sold. I realized, in looking back at the previous stories, that while I had written about identity and belonging and sexuality, about characters fighting for or against something, I hadn’t quite written about the community itself. To me, “World Famous” is about the devastating power of society, how it pushes and pulls us, sometimes forcing us to lie.

I wrote “World Famous” first, but by the end of it I knew there was more. We saw Anjali through Ankur’s eyes; I wanted to see him through hers. There seemed to be an urgency to their stories, and they came to me rather quickly. I wrote both stories back to back, and what would normally have taken months to revise only took a few weeks, about two or three drafts. By then I had been blessed with an editor who could recognize where I wanted to go and helped me get there much faster.

How has your writing process evolved?

Writing never came easily to me. It took months, if not years, to complete a single story. For a while, I was my own editor. I wasn’t in an MFA program and didn’t have any literary friends. I was forced to judge the quality of my work against that of the writers I loved—something no writer should do if they want to remain sane—but as time went on, I got better. I learned that writing is mostly about figuring out what isn’t working and addressing that. I started sending my work out to journals and listening to their replies. I was fortunate to have a few editors like yourself and Lou Ann [Walker] give me a chance. By the time I connected with my current editor, I had learned how to process a reader’s comments and what to do with them. Writing is a bit like designing a puzzle: You’re creating the pieces, but you’re also figuring out how they all fit together. It helps to have a second pair of eyes.

You comfortably shift between genders and sexual identity in your narrators. Is the point of view something that’s present when you begin a story?

I start with voice when writing each of my stories. Sometimes that voice is female, sometimes male, sometimes queer, sometimes straight. It all depends on what I’m trying to say. Sometimes I realize, later on, that the character isn’t who I thought they were. For example: when I first started writing “Just a Friend,” the narrator was a woman. It wasn’t until a couple pages later that I realized this character was actually a man. It became an entirely different story. That is the enormous power of perspective in literature. By changing one thing, you have managed to change everything.

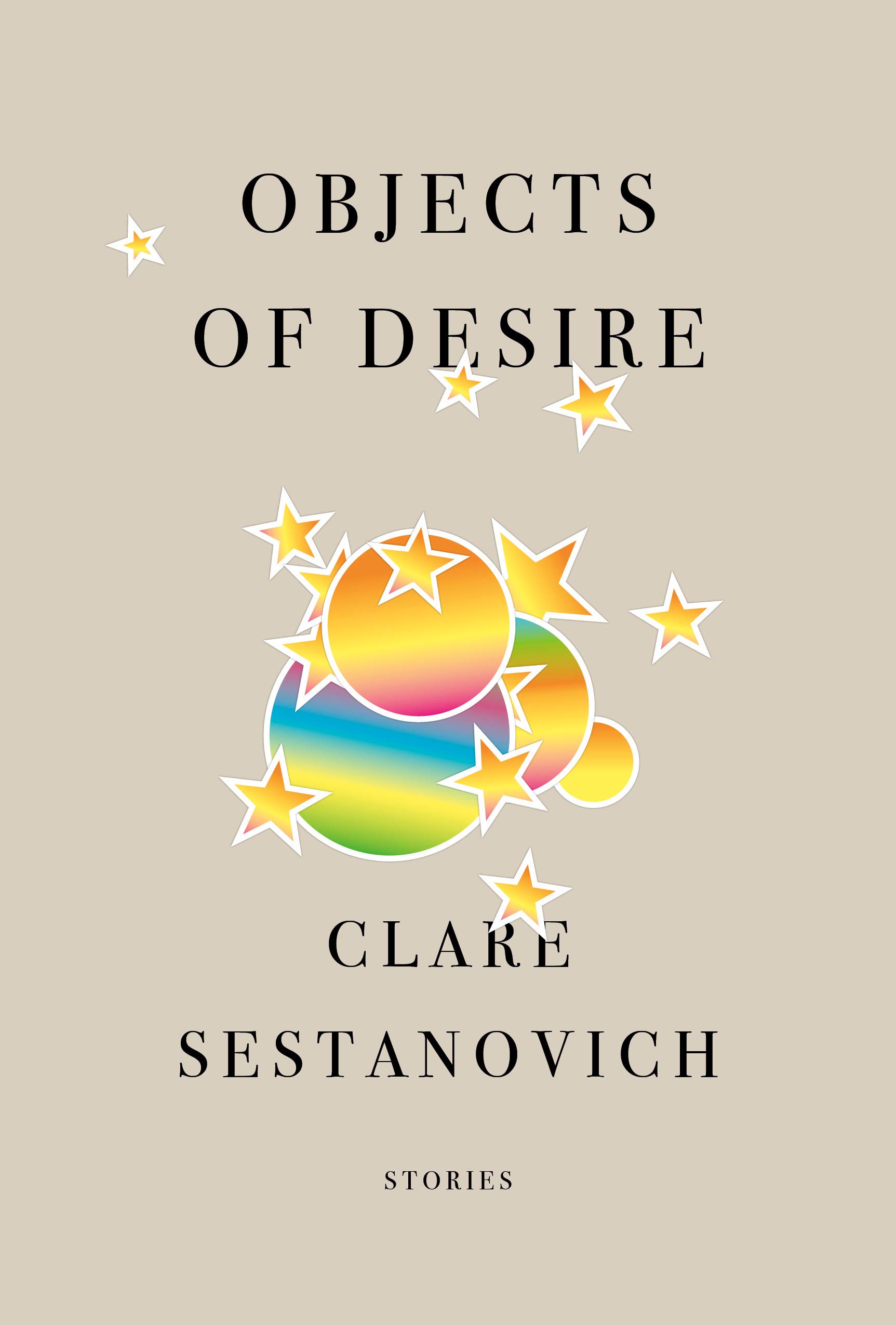

I’m interested in the cover of the book and how it came to be. My first impression is that the color palette represents skin tone.

You can’t be an American without thinking about race. It’s embedded in our history. It still divides and defines us. Being brown is a peculiar experience because, from a young age, I’ve only ever seen America as being white and black. I found that in school white kids were either dismissive of or curious about me, while black kids saw me as an ally when no other black kids were around. It was important to have the narrator of the title story pursue white girls. Growing up, the standard of beauty was white, the images you saw on magazine covers and on TV screens were of fresh-faced white women. In school, the celebrated students, the ones who were sought-after were almost always white. It would make sense for brown men to romanticize the experience of being with a white girl. This can also be traced back to British colonialism, and its effects on the mindset of Indian men.

I was fortunate to have had my cover designed by the talented Keith Hayes, but I’m embarrassed to say that my original idea wasn’t very original. I had imagined something more recognizably Indian. Keith came up with this. Recently, I was thanked by another Indian writer for having a book cover that didn’t contain a woman in a sari or some kind of Indian motif. I love Keith’s interpretation. It’s modern and unexpected, just like the book. I do think the cover could represent skin tones. To me, it’s a reminder that there’s more than one shade of brown.