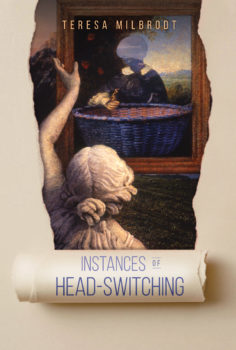

While reading Instances of Head Switching, Teresa Milbrodt’s newest story collection, which has just been published by Shade Mountain Press, I noticed almost immediately a key difference between it and other fiction with fantastical themes I’ve read: the theme is beside the point. The elements of fantasy are written as ordinary, even in the characters’ responses to them. The point, instead, seems to center on the relatable struggles of the working class, often differently abled, female. This unique spin on a genre I have, admittedly, little experience with, raised questions in my mind that I hoped to have a chance to ask the author. So I reached out to her for an interview.

Teresa Milbrodt is the author of other short story collections, including Bearded Women and Work Opportunities; the flash fiction collection, Larissa Takes Flight; and a novel, The Patron Saint of Unattractive People. She has an M.F.A. from Bowling Green State University and a Ph.D. from the University of Missouri. She teaches at Michigan State University.

Interview:

Elizabeth Earley: How did you come up with the ideas for the stories in Instances of Head Switching? Were they approached individually or combined as a collection?

Teresa Milbrodt: I’ve tended to compile my short story collections over seven to ten years. I write both realism and literary fabulism, so these books have emerged organically as I’ve collected stories that have a thematic resonance. That said, the ideas in this book are ones that I often engage with in my work: economic instability, body variability, and people who, for one reason or another, find themselves at the fringes of society. I also love to play with themes from folktales and Greek mythology, so that’s a thread in the collection as well.

The stories seem to have two elements in common: magical realism and differently abled bodies. Did you mean for the former to be a byproduct, or a function, of the latter?

I’ve been blind in my right eye almost since birth. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized how much having a disability affected how I viewed the world, both in a literal and metaphorical sense, and how it shaped my personality. Yet, in much of the fiction that involves disability, it’s cast as the problem that has to be overcome, not simply an aspect of one’s embodiment. I want to help advance the kind of crip lit in which people with disabilities are living their lives and doing perfectly fine, to highlight and differentiate the times when disability does and does not matter.

I’ve been blind in my right eye almost since birth. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized how much having a disability affected how I viewed the world, both in a literal and metaphorical sense, and how it shaped my personality. Yet, in much of the fiction that involves disability, it’s cast as the problem that has to be overcome, not simply an aspect of one’s embodiment. I want to help advance the kind of crip lit in which people with disabilities are living their lives and doing perfectly fine, to highlight and differentiate the times when disability does and does not matter.

Disability plays into some of these stories because it’s a character trait that affects how that person moves through their space, and structural barriers that prevent them from moving, but the heart of the story is elsewhere. In other stories, fantastic elements serve as a means to make the invisible disability visible. For example, many people have conditions such as chronic pain and fibromyalgia, which can’t be detected visually or on any scan, but which greatly affect how an individual lives their life, especially when their pain is not believed by others. In a couple of these stories, the fabulist element comes into play when exploring the control people are expected to have over mediating their emotions, particularly when communicating with others. In these ways, fabulism is a means to explore some of the difficult gray areas around bodies, the many ways disability can manifest, and how individuals may adapt to an ever-changing corporeal self.

Do you have a favorite story, or one that was the most fun to write?

I enjoyed writing “White as Soap,” since I’m enamored with this rather gritty version of unicorns. They don’t sparkle, they’re not magic, they’re horses with horns. They’re lovely as all horses are lovely, and they don’t smell too great. I suppose there’s something contrarian in me that delights in making the mystical a bit less so.

For that reason I also enjoyed writing the story “Costume Control,” and playing with all the ways magical amulets could backfire. That story is also based in part on my own experiences, since people have often asked me if I’d have surgery to restore the sight in my blind eye if such were possible. Most folks seem confused when I say no, but living with this disability is part of my normal, and I wouldn’t have become the same me without it. I wanted to play with that idea of refusing a “cure,” examining both the potential negative aspects of treatment and how some people see disability as part of their identity because they’ve never known their bodies to be any other way, and so they don’t need or want to be changed.

Did you have social or societal themes in mind when writing these stories? Were the magical realism elements symbolic of these? In particular, what do the little people from the old country living in grandma’s couch symbolize? Any other symbolism you would care to describe from any of the stories?

I definitely had social themes in mind, as I’ve mentioned. One of the primary themes is seeing disability not as tragedy, but as something people can adapt to, live with, and consider integral to their sense of self. At the same time, I wanted to capture the variability of disability and how no two people will view their condition in the same way. Disability can be part of one’s identity, it can be a point of pride, and it can be a literal pain such as with invisible disabilities like arthritis and chronic fatigue. My stories just start to touch on that complexity.

Economics and work is another theme in this collection, and often it’s related to disability. I’m exploring a number of questions along these lines: Who can find work? What kind of work can they find? How hard does one have to work to make ends meet? What are the physical and emotional costs of that work? What happens when one’s job becomes an integral part of one’s identity and it’s hard to separate the two? What are the pitfalls of living in a society where we base so much of an individual’s perceived worth on the work they do, and how much money they make?

When I write I’m not consciously thinking about symbolism, but it’s interesting to see what emerges after I finish a draft of a story, and the meanings that certain elements might take on. In “Berchta” I was drawing on German folktales. In retrospect the little people in Grandma’s couch could reflect traditions that were passed down in the speaker’s family and lost to her generation, or aspects of her upbringing that she doesn’t even recognize as tradition.

The fabulist elements in my stories definitely come into play regarding work, and the sacrifices people make to do their jobs. Particularly in stories such as “Marbles,” “Head-Switching,” and “The Dreamlords,” I wanted to use fabulism to investigate the physical and emotional toll that work can take on people. Similar to my explorations of invisible disability, fabulism serves as a means to make the consequences of work visible, and emphasize that weight.

The fabulist elements in my stories definitely come into play regarding work, and the sacrifices people make to do their jobs. Particularly in stories such as “Marbles,” “Head-Switching,” and “The Dreamlords,” I wanted to use fabulism to investigate the physical and emotional toll that work can take on people. Similar to my explorations of invisible disability, fabulism serves as a means to make the consequences of work visible, and emphasize that weight.

What are you working on now?

I have a couple ideas for novel projects that I’m bouncing around, one realistic and the other literary fabulist. Both projects involve characters with disabilities as protagonists, and the play between disability as a political identity, disability as a real physical pain, and the social stigmas surrounding disability. I’m also setting one of the novels outside the U.S., and examining how the meaning of disability can shift radically in different environments. My protagonist has to confront a lot of social and physical barriers she never dealt with before, which makes her grapple with the level of privilege she’s had throughout her life but not had to acknowledge.

Anything else we should know?

In fiction and in life, play is vital to learning. I use fabulism in my writing to play with the comic, the absurd, and what-ifs, imagining the world through a different lens to see what I can uncover by tweaking reality a bit. Sci-fi and fantasy writers have always known that we have to reflect people back to themselves through a slightly distorted mirror, allowing readers to re-see reality.

At times like these, when everything seems chaotic and hopeless, we have the opportunity as artists to give people an escape from the present, a different way of seeing it, and possibilities for (re)shaping the future. That’s one way that fiction writers can make our mark as social activists, and that’s where I see myself writing from, a creative lineage of play and possibility and, dare I say, hope.