I was worried that grad school at Columbia College – Chicago was going to be an uncomfortable experience, full of boring snobs. During the second week of class, we read a short story that proved me wrong. It was told by a woman whose husband ruined an expensive and tacky Halloween costume in an effort to impress another woman at their neighborhood bar. In that story, I heard humor and real-life dilemmas that felt closer to my life than the headier, ritzier things I was scared I’d be subjected to in an MFA program. That story made me feel good about my decision to quit a stable job and go into debt chasing my writing dream. Jessie Ann Foley had turned that story in.

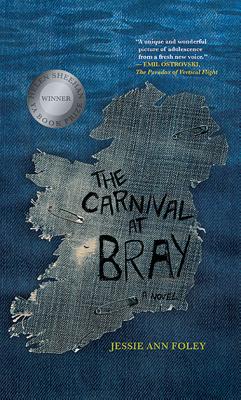

Throughout school, I loved all of Jessie’s stories—in class, at readings, or in her multiple appearances in the Chicago Reader’s fiction issue. It didn’t hurt that Jessie, an Irish-American woman from the part of Chicago’s Northwest Side where cops live, could very well be a long-lost cousin on my mom’s side of the family. Her debut novel, The Carnival at Bray (Elephant Rock Books), follows Chicago teenager Maggie to Ireland, where her serial-romantic mother has found her latest love. Over the course of a school year, Maggie repeats some of her mother’s mistakes as she begins carving out her own life, a continent away from home.

Bray nails the teenage feeling of everything being life or death. It’s one of the best books that I read this summer, and I was pleased to discuss it, along with parenting, our beloved decade the ‘90s, and those awkward moments when your family read your writing, with the author.

INTERVIEW:

Chris L. Terry: Young Adult novels tend to be written in first person. Why did you choose to write The Carnival at Bray in third?

Jessie Ann Foley: When I write in first person, I tend to ramble; maybe that’s from all the diary writing I did as a kid. First person is useful to me when I’m still trying to figure out who a character is. But once I understand the character, third-person writing, at least for me, is a lot tighter and allows me to articulate things better.

What’s the process there? Do you go as far as changing “I” to “She?”

No, I never really switch points of view once I’ve already started writing a story. I experiment more in my journal, mainly because I’m lazy, and once I’ve started writing a story in, say, third-person limited, it’s too much of a pain to go back and change it into something else.

Tell me about working on the Irish characters in Bray. How did you write their dialogue?

My husband, Denis, who is from County Kerry, was a huge help. I tortured him with constant, nitpicky questions relating to word choice, slang, and authentic details: what do you call those bales of hale covered in plastic? What is the hurling equivalent of a quarterback? What kind of beverage would a young Irish kid drink if his father took him to the pub? Things like that. If there was a passage that contained lots of dialogue—Eoin’s long monologue about his mother comes to mind—my husband would read it aloud and help me figure out what needed tweaking. I was so nervous for him to read the first draft of the book, because I knew I was going to make ridiculous mistakes. But he was polite enough not to make fun of me.

My husband, Denis, who is from County Kerry, was a huge help. I tortured him with constant, nitpicky questions relating to word choice, slang, and authentic details: what do you call those bales of hale covered in plastic? What is the hurling equivalent of a quarterback? What kind of beverage would a young Irish kid drink if his father took him to the pub? Things like that. If there was a passage that contained lots of dialogue—Eoin’s long monologue about his mother comes to mind—my husband would read it aloud and help me figure out what needed tweaking. I was so nervous for him to read the first draft of the book, because I knew I was going to make ridiculous mistakes. But he was polite enough not to make fun of me.

You are Chicago born and raised. Tell me about the choice to set most of your book in Ireland.

The Carnival at Bray was originally a short story that I published in the Chicago Reader after visiting a forlorn carnival fairground in County Wicklow in 2010. I’m Irish-American, but as Maggie learns in the first chapter, that identity can have very little to do with what it means to be actually Irish, and if I had known then that I was setting myself up for the task of expanding it into an entire novel set in Ireland, I might have made things easier for myself and kept Maggie in Chicago. But then, she would never have met Eoin.

When did you first visit Ireland? Tell me more about realizing that there is this difference between being Irish and Irish-American.

One only need be in Chicago on Saint Patrick’s Day to see that it no longer is a holiday dedicated to Irish culture, but to Bud Light and shamrock deedly-boppers. The whole Irish-American identity has been commercialized: Irish pubs, Irish baby onesies, the Fighting Irish, any movie about scrappy Bostonians in warm-up pants, because the Irish are seen as fun, charismatic underdogs, and who doesn’t want to be a part of that? America is the only place where people say, “I’m 25% Polish, 25% Puerto Rican,” etc. It was always a point of pride in my family that we were “100% Irish,” so when I left the country for the first time at age twenty to study abroad in Cork, I was sort of surprised that Ireland was actually foreign. That was the first time someone said to me, puzzled, “But you’re not Irish. You’re American.” Which was, of course, true. Maggie has that same realization in chapter one.

Why is your book set in the 1990s? I set Zero Fade in 1994 and Kirkus listed it as Historical Fiction. I felt my age then.

People might think that I set the book in the ‘90s because that’s when I was Maggie’s age, with the implication being that she is a prototype of myself, but that’s not true at all. Maggie and I were very different teenagers—she was a lot cooler, smarter, and tougher than I was. She also had better taste in music and men. And she learned from her mistakes a lot quicker than I did.

The truth is, setting the novel in the ‘90s solved some very important plot problems, the obvious one being the absence of social media. In order for Maggie to grow in the way she needed to, I felt like she needed to be truly isolated in Bray—truly marooned in this new country. If she’s following Selfish Fetus on Facebook, if she’s Skyping with Nanny Ei, she’s still got one leg immersed in Chicago, and the need to find her way in Ireland is not as urgent. With the lack of Internet access, it’s harder to go back. She’s stuck, and she needs to show her mettle.

The other thing is—and I know every generation says this—I just can’t think of any band today that has the capacity for life-alteration that Nirvana had in the early ‘90s. And part of that relates back to social media. How mythical would Kurt Cobain be if he’d left behind a trail of Instagram selfies? If he Tweeted?

And perhaps that is why he has no equivalent today, and why today’s teenagers still idolize him as much as the young people of his own time did. We just know too much about today’s celebrities—and that makes them far less interesting, far less romantic.

I was thinking a bit about this today. Before I had the Internet, I’d regularly drop $18 on albums I hadn’t heard. Sometimes they’d be awful. I don’t miss that. I was just celebrating that lack of mystery today while at the record store. Surely there are advantages to the Internet?

Of course there are. But the ubiquity of celebrities isn’t one of them, in my opinion.

You recently had your first child, a daughter. What’s it like to imagine your kid reading your book about teenagers?

It’s weird. My daughter is only three months old, so it’s hard to imagine her as a little girl, let alone a teenager. I’m still getting over the fact that I’ve already had to put away her newborn clothes. But one day she will be older, and I hope she reads the book and likes it—I hope it makes her proud of me. What makes me far more uncomfortable is the idea of my parents reading the book, mainly because of the sex scenes. I’ve already warned them that this is fiction, and that none of this stuff actually happened to me, but I’m not sure that they’ll believe me.

My first kid’s coming in October. Tell me about finding time to write with a baby around. Please tell me that I will write again!

There’s that famous quote, “There is no more somber enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.” But the writer Anne Enright put her own spin on it that I like better: “We now know that the pram in the hall was not so much the enemy of great writing, as of great drinking.” I don’t know if I’ll be able to finish my next novel in a year, as I did with Carnival at Bray, but I’m okay with that. If anything, having a baby takes the pressure off: I feel like, even if my book flops, even if I never write another word, I still have a beautiful, healthy kid who I’m madly in love with, so things could be a lot worse.

How has you family responded to your writing in the past? I know that you write a lot about the Northwest side of Chicago, where you grew up. My mom is totally on alert after I wrote something about our family. Last Christmas, she was making comments to my dad like, “Don’t show him your socks. They’ll be in his next book.”

Totally. They always mine my work for what’s “real” and what’s made up. I’ve already rehearsed the speech I’m going to give my parents before they read Carnival at Bray, about how Maggie is not me, and everything that happened to her is made up. Especially the sex parts.

Ha! Yeah. I want my people to just enjoy the writing, instead of picking through for the “real” parts, but then I read a friend’s book and think, “Oh, that’s totally their mom.” And, shoot, I included some inside jokes in Zero Fade. I think this ties back to the new transparency that we get with social media. Since we get this mediated access to famous strangers’ lives, we expect everything to be based on real life. Be careful what you wish for, I guess.

Moving on, why did you choose to write this book as a YA novel?

Moving on, why did you choose to write this book as a YA novel?

I’ve been a high school English teacher for ten years, and I think being surrounded by kids all day has helped me to remember what it’s like to be young. I certainly wouldn’t want to go back to those years, but I still think it’s such a cool age. When you’re fifteen, everything is new and fresh; so much life happens. But even when things are going well, there’s that constant unanswered question: what am I going to do with my life? I remember sitting in my high school AP English class, and we were reading “A Tree, a Rock, a Cloud,” by Carson McCullers. God, I loved that story, even though I didn’t really understand it and still probably don’t. But in it, this man talks about the science of love, the risks you undertake when you let yourself love someone, and I remember wondering would I ever fall in love—like really fall in love, and would I get married, and would I have children, and what kind of job would I have… I just remember my mind spiraling because I knew everything was ahead of me and I had no idea how it was all going to turn out and that was both scary and wonderful. The process of growing up has inherent drama; it lends itself to good stories. And that’s why YA lit is such a great genre, and why teenagers are often great protagonists: because they are people in crisis, people who are striving for something.

What did you do differently than if you were writing for an adult audience?

Honestly, not much. I think adults are really bad at remembering what it’s like to actually be a teenager—there are so many movies and TV shows about high school, but only a sliver of them portray that stage of life in even remotely accurate terms—and if I had set out to consciously write for a teenage audience, I feel that my book would have come across as inauthentic. That said, my editor, Jotham Burrello, had a fantastic ear for inconsistency of voice. When Maggie sounded more like a thiry-year-old trying to sound like a teenager, he called me out on it, and that’s where a lot of the revisions happened.

There’s a weird gap between the ways that teenagers act, think, and speak, and the media that they’re allowed to consume. I feel like all that fourteen-year-old me did was curse and (unsuccessfully) scheme on how to get laid, but a book or movie that was true to that would be obscene.

Ha! Fourteen-year-old boys are, by nature, obscene. Luckily, there are fourteen-year-old girls around to love them.

How did you find Elephant Rock Books? What was it like working with them?

They were having a contest to start their new YA imprint. I submitted The Carnival at Bray, even though I wasn’t sure if it could be considered YA, and it won. They were marvelous to work with. Jotham and I worked closely for four months on the edits. We finished two days before I gave birth.

What else are you working on?

I just published a new short story that I’m really proud of, “The Day of New Things,” in Midwestern Gothic. I’m also working on a new novel about an all-girls Catholic school in Chicago that is in danger of closing down. I’ve also got a short story collection, Neighborhood People, in the works. And I’ve got a million half-finished essays littering the desktop of my computer, about teaching, motherhood, baby yoga class, The Grapes of Wrath, road tripping, William Carlos Williams, and organic cherries. Of course it’s a lot harder to write for a sustained period of time now that I have a baby, but if I’m not working on something, no matter how terrible or how scattered, I don’t really feel like myself.