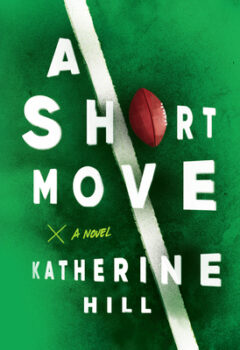

I was nostalgic for the frivolity of past football seasons while reading A Short Move. It reminded me that we used to worry about injuries, game day weather, and turf conditions rather than virus outbreaks and team quarantines. And in Katherine Hill’s second novel, you can still hear the marching band, grab a concession stand hot dog during halftime, and raise your voice with the cheerleaders. But this book is also a behind-the-scenes tour of our favorite American pastime, immersing readers in the world of football that we don’t often see on the field—one that reveals an ecosystem that defeats and exploits talent as much as nurtures it, exposing the price of fame and the allure of an American Dream only accessible to the chosen few.

The protagonist, Mitch Wilkins, is one of those elite players expected to deliver glory. Though despite his promise, the NFL quickly consumes him. And the story of his rise and fall is chronicled not only by Mitch himself, but also by his team: his uncle, who serves as a kind of father figure; his exhausted mom, who patiently yet insistently prods her son’s dreams; and his girlfriend, who has ambitions of her own—along with his chatty teammates, an opportunistic billionaire owner, and several others who drift in and out of Mitch’s life on the uncertain arc of his career path. But what is unwavering is the drive down the field to insatiable power and the community that lives for the promise. Or, in writers’ terms, the promise and pain of the second book—something Katherine and I both can relate with.

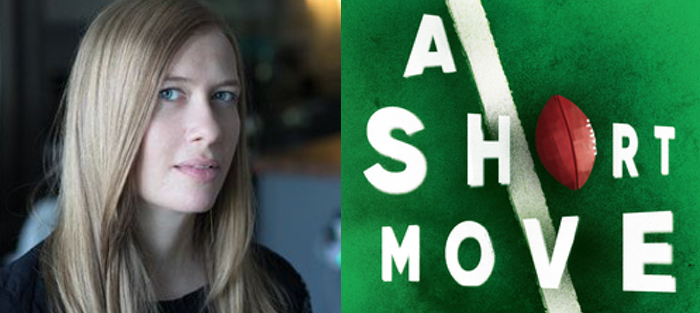

In addition to A Short Move (Ig Publishing), Katherine Hill is the author of a previous novel, The Violet Hour (Scribner 2013), which was a New York Times Editors’ Choice. She is also co-author of The Ferrante Letters: An Experiment in Collective Criticism (Columbia University Press 2020). Her writing has been awarded fellowships from the New York Public Library, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Corporation of Yaddo. She is an assistant professor of English at Adelphi University, where she teaches creative writing and literature to undergraduate and MFA students. Born in Washington D.C., Hill now lives with her husband and daughter in Brooklyn.

Six years ago, the author and I met up for an interview when The Violet Hour debuted. This time, we met up via Zoom, where we both find the chasing of children off screen harder to hide. Still, it was a pleasure to be chatting books and life again.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: It seems any book released in 2020 is a miracle. What has your experience been publishing during a pandemic?

Katherine Hill: I think at a different point in my life it would have been a huge disappointment. We hear a lot about how horrible it is for people who launched a book in 2020, and that’s obviously true. But my experience was so different, because I had a delightful baby at home and I had also just published this other book about Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, The Ferrante Letters, which my coauthors and I launched in person in January, so I sort of felt like I wasn’t missing anything. By the time A Short Move was published, the whole world was locked down; it wasn’t like anyone else was having book talks and parties.

I can imagine this was so different than your debut publishing experience.

It kind of felt freeing. The book was still there, on the internet, where everything lived at that time. And people were still buying books. I got emails and texts and news notifications all summer long.

You’ve written a football novel without a lot of football. We’re absorbed in story rather than play by play.

It’s only sort of a football book. How did you read it? I’m curious.

I think it’s a story about the American dream and its failings. When you are a sports star like Mitch and your career ends, it’s divorces, drama, and retirement. You have to ask ‘what’s next?’ when you’re still in the prime of your life. Mitch is so likeable and sad. I think it’s a warning about a long happy life vs. rock-star fame.

Yes, that whole question about what is the prime of life. I really began with the idea of a premature old age. I wrote a story about Mitch’s daughter, Alyssa, that I published in 2012. She drops out of college, and goes to work in retail. And her dad is this minor character in the background, who has grown distant from her. My editor asked me if was part of something larger. It wasn’t, but sometimes you just need someone to ask you the question. So I spent some time thinking, and I realized the person I was most curious about in the story was that father, who at the time was retired and already an old man. I decided I wanted to get to know him better, so I wrote a story about him on his way to college, basically the same age as Alyssa. I felt a strong desire to draw a line between the two of them.

Yes, that whole question about what is the prime of life. I really began with the idea of a premature old age. I wrote a story about Mitch’s daughter, Alyssa, that I published in 2012. She drops out of college, and goes to work in retail. And her dad is this minor character in the background, who has grown distant from her. My editor asked me if was part of something larger. It wasn’t, but sometimes you just need someone to ask you the question. So I spent some time thinking, and I realized the person I was most curious about in the story was that father, who at the time was retired and already an old man. I decided I wanted to get to know him better, so I wrote a story about him on his way to college, basically the same age as Alyssa. I felt a strong desire to draw a line between the two of them.

That makes so much sense related to the structure. Talk about the time lapse or more your decision to dip into these periods in Mitch’s life. You followed a similar nonlinear fashion in The Violet Hour.

I am so interested in the way personality traits express themselves over time, and our hopeless attempts to know ourselves and others in time. Fiction is a fantastic medium for playing with temporal problems.

I can see how that leads to different point of views. Close third to Mitch, but we also get the story through the eyes of coaches, parents, wives, other players, etc. POV shifts for sure but the voice is consistent. I’m curious if you knew immediately that you wanted this chorus—really a team approach—or if you considered Mitch in first-person pov.

It was always going to be about an athlete who belongs to others more than himself, who belongs to a team, to the fans. But as I was writing, I didn’t find myself wanting to take points of view from his workplace. I was most interested in the points of view closer to him—his family, who he also belongs to, even as he’s pulled away from them. The very first perspective I had was his daughter. The next perspective was his dad, then his mom, then his wife. The most distant perspectives are still familial in some way: a teammate who’s like a brother and a fan from his hometown in Central Virginia.

Even though we’re often in Mitch’s head, he doesn’t feel that accessible. He’s only focused on football. I never know how Mitch feels.

I don’t think Mitch knows how he feels. I mean you see him at the end, in therapy, just playing games. Not really doing the work. A master of sublimation. But I sublimate, too—like all of us.

If you’re not a football player, how do you enter that space of sports that fuels your imagination?

For me, research was it. I just read a ton. I read a lot of athlete memoirs. And I watched a lot of games and interviews with athletes. I watched “Hard Knocks,” which is a show about the NFL on HBO. And there was a great YouTube Show called “The Real Rob Report” with Mike Robinson. He was a fullback for the Seattle Seahawks who loved interviewing his teammates, offering a player’s perspective on the work they do. The idea that it is work was really important to me, and all of those sources helped me understand the job. They gave me the confidence to take an imaginative leap. I wasn’t telling a true story. But I was writing about a world that does exist.

How did you access that world to make it real on the page?

I was very lucky to tour a few NFL spaces, most helpfully the practice facility for the Baltimore Ravens. I can still see the meeting room where the players kept a trashcan filled with candy. And I can still see the motivational slogans taped on the walls like flyers for school events. The fastidiously clean hallways, the impeccably organized equipment room.

Have you always been a football fan?

I’ve been watching it for as long as I can remember. I think it scared me initially, as a really small child, because, you know, it’s big men colliding at high speed. The first football game I ever went to was at Denison University in Ohio, and I remember I tripped and skinned my knee on a concrete stadium step. So despite never having played, I have an early association of football with pain. But I also love the sport. It’s a big part of my marriage. It’s a connection to the many places where I grew up. And it activates the little world-builder in my head. I played fantasy football for many years.

Is it complicated to write about masculinity? Mitch doesn’t know his father. It’s really Uncle Tim who fills that role. He’s his first coach, his champion, his male role model.

I was very aware that I was an intellectually oriented woman writing a physically oriented man. The challenge was right there in front of me. I have a pretty critical mind, but I also truly wanted to understand American masculinity. I couldn’t have written this book without both of those impulses.

I don’t think you could have written a more American novel for this moment. Football was threatened because of COVID and people’s reactions were so emotional. It wasn’t just about the game; it was about the community. It was about everyone coming together. The ecosystem of sports. Teammates, coaches, owners, fans. Therapists, doctors, scientists, ministers. What is the allure that draws everyone in?

For so many Americans, including myself, football is a central part of life. There’s a ritualistic quality to it, with the weekly games, always on the same day of the week, in the same season of the year. There’s the sense of tradition attached to playing on or supporting a particular team. In contemporary life, sports are a lot like politics or religion in that they activate these very deep-seated affinities, which we re-enact continuously, and often without examination. I’m trying to do some of that examination here, as a fan who participates in the culture, but also observes it from a distance. The desires for community, togetherness, and transcendence in football are impossible ignore, but so is the hyper-corporate nature of the game—by far the most profitable in the country.

I wonder how much football is just the gateway to talk about the cost of capitalism and the allure of power.

Absolutely! I was interested in redistributing narrative power by giving voice to figures behind the conventional scenes—including the player-worker himself! But it’s a nice trick that redistribution of any kind always reveals the unequal structures that exist.